Hungarian People's Republic

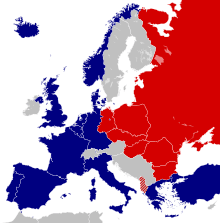

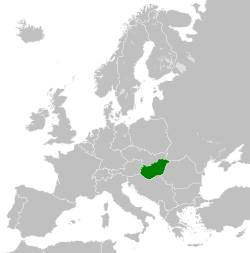

The Hungarian People's Republic (Hungarian: Magyar Népköztársaság) was a one-party socialist republic from 20 August 1949[5] to 23 October 1989.[6] It was governed by the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, which was under the influence of the Soviet Union.[1] Pursuant to the 1944 Moscow Conference, Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin had agreed that after the war Hungary was to be included in the Soviet sphere of influence.[7][8] The HPR remained in existence until 1989, when opposition forces brought the end of communism in Hungary.

Hungarian People's Republic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949–1989 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Member of the Warsaw Pact (1955–1989) Satellite state of the Soviet Union[1] | ||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Budapest 47°26′N 19°15′E | ||||||||

| Official languages | Hungarian | ||||||||

| Religion | Secular state (de jure) State atheism (de facto) Roman Catholic (dominant) | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Hungarian | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary Marxist-Leninist one-party socialist republicUnder a totalitarian dictatorship (1949–1953)[2] | ||||||||

| General Secretary | |||||||||

• 1949–1956 | Mátyás Rákosi | ||||||||

• 1956 | Ernő Gerő | ||||||||

• 1956–1988 | János Kádár | ||||||||

• 1988–1989 | Károly Grósz | ||||||||

• 1989 | Rezső Nyers | ||||||||

| Presidential Council | |||||||||

• 1949–1950 (first) | Árpád Szakasits | ||||||||

• 1988–1989 (last) | Brunó Ferenc Straub | ||||||||

| Council of Ministers | |||||||||

• 1949–1952 (first) | István Dobi | ||||||||

• 1988–1989 (last) | Miklós Németh | ||||||||

| Legislature | Országgyűlés | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 31 May 1947 | |||||||||

| 20 August 1949 | |||||||||

| 14 December 1955 | |||||||||

| 23 October 1956 | |||||||||

| 1 January 1968 | |||||||||

• Third Republic | 23 October 1989 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 93,011[3] km2 (35,912 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1949[4] | 9,204,799 | ||||||||

• 1970[4] | 10,322,099 | ||||||||

• 1990[4] | 10,375,323 | ||||||||

| Currency | Forint (HUF) | ||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||||||||

| UTC+2 (CEST) | |||||||||

| Date format | yyyy.mm.dd. | ||||||||

| Driving side | right | ||||||||

| Calling code | +36 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early history

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The state was considered itself the heir to the Republic of Councils in Hungary, which was formed in 1919 as the first communist state created after the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR). It was designated a people's democratic republic by the Soviet Union in the 1940s. Geographically, it bordered Romania and the Soviet Union (via the Ukrainian SSR) to the east; Yugoslavia to the southwest; Czechoslovakia to the north and Austria to the west.

Having emasculated most of the other parties, the Communists spent the next year and a half consolidating their hold on power. This culminated in October 1947, when the Communists told their non-Communist coalition partners that they had to cooperate with a reconfigured coalition government if they wanted to stay in the country.[9] In June 1948 the Communists forced the Social Democrats to merge with them to form the Hungarian Working People's Party (MDP). However, the few independent-minded Social Democrats were quickly shunted aside, leaving the MDP as a renamed and enlarged Communist Party. Rákosi then forced Tildy to turn over the presidency to Social Democrat-turned-Communist Árpád Szakasits. In December, Dinnyés was replaced by the leader of the Smallholders' left wing, the openly pro-Communist István Dobi. The process was more or less completed with the elections of May 1949. Voters were presented with a single list of all parties, running on a common programme. On 18 August, the newly elected National Assembly passed a new constitution—a near-carbon copy of the Soviet Constitution. When it was officially promulgated on 20 August, the country was renamed the People's Republic of Hungary.

The same political dynamics continued through the years, with the Soviet Union pressing and maneuvering Hungarian politics through the Hungarian Communist Party, intervening whenever it needed to, through military coercion and covert operations. Rajk called it "a dictatorship of the proletariat without the Soviet form" called a "people's democracy."[10] Political repression and economic decline led to a nationwide popular uprising in October-November 1956 known as the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, which was the largest single act of dissent in the history of the Eastern Bloc. After initially allowing the Revolution to run its course, the Soviet Union sent thousands of troops and tanks to crush the opposition and install a new Soviet-controlled government, killing thousands of Hungarians and driving hundreds of thousands into exile. But by the early 1960s, the government had considerably relaxed its line, implementing a unique form of semi-liberal Communism known as "Goulash Communism". The state allowed in certain Western consumer and cultural products, gave Hungarians greater freedom to travel abroad, and significantly rolled back the secret police state. These measures earned Hungary the moniker of the "merriest barrack in the socialist camp" during the 1960s and 1970s. [11] One of the longest-serving leaders of the 20ths century, Kádár would finally retire in 1988 after being forced from office by even more pro-reform forces amidst an economic downturn. Hungary stayed that way until the late 1980s, when turmoil broke out across the Eastern Bloc, culminating with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union's dissolution.

History

Formation

Following the occupation of Hungary by the Red Army, Soviet military occupation ensued. After seizing most material assets from German hands, the Soviets tried, and to a certain extent managed, to control Hungarian political affairs.[12] Using coercion through force, the Red Army set up police organs to persecute the opposition, assuming this would enable the Soviet Union to seize the upcoming elections, in conjunction with intense communist propaganda to attempt to legitimize their rule.[13] The Hungarian Communist Party, despite all the efforts, was trounced, receiving only 17% of votes, by a Smallholder-led coalition under Prime Minister Zoltán Tildy, thus frustrating the Kremlin's expectations of ruling through a democratically elected government.[14]

The Soviet Union, however, intervened through force once again, resulting in a puppet government that disregarded Tildy, placed communists in important ministerial positions, and imposed several restrictive measures, like banning the victorious coalition government and forcing it to yield the Interior Ministry to a nominee of the Hungarian Communist Party.

Communist Interior Minister László Rajk established the ÁVH secret police, in an effort to suppress political opposition through intimidation, false accusations, imprisonment and torture.[15] In early 1947, the Soviet Union pressed the leader of the Hungarian Communists, Mátyás Rákosi, to take a "line of more pronounced class struggle." American observers likened communist machinations to a coup and concluded that "the coup in Hungary is Russia's answer to our actions in Greece and Turkey,"[16] referring to US military intervention in the Greek Civil War and the building of US military bases in Turkey pursuant to the "Truman Doctrine."

Rákosi complied by pressuring the other parties to push out those members not willing to do the Communists' bidding, ostensibly because they were "fascists." Later on, after the Communists won full power, he referred to this practice as "salami tactics."[17] Prime Minister Ferenc Nagy was forced to resign as prime minister in favour of a more pliant Smallholder, Lajos Dinnyés. In the elections held that year, the Communists became the largest party, but were well short of a majority. The coalition was retained with Dinnyés as prime minister. However, by this time most of the other parties' more courageous members had been pushed out, leaving them in the hands of fellow travellers.[18]

Stalinist era (1949–1956)

| Eastern Bloc | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

|

Allied states

|

|||||||

|

Related organizations |

|||||||

|

Dissent and opposition

|

|||||||

Mátyás Rákosi, the new leader of Hungary, demanded complete obedience from fellow members of the Hungarian Working People's Party. Rákosi's main rival for power was László Rajk, who was then Hungary's Foreign Secretary. Rajk was arrested and Stalin's NKVD emissary coordinated with Hungarian General Secretary Rákosi and his State Protection Authority to lead the way for the show trial of Rajk.[19] At the September 1949 trial, Rajk made a forced confession, claiming that he had been an agent of Miklós Horthy, Leon Trotsky, Josip Broz Tito and Western imperialism. He also admitted that he had taken part in a murder plot against Mátyás Rákosi and Ernő Gerő. Rajk was found guilty and executed.[19]

Despite their helping Rákosi to liquidate Rajk, future Hungarian leader János Kádár and other dissidents were also purged from the party during this period. During Kádár's interrogation, the ÁVH beat him, smeared him with mercury to prevent his skin pores from breathing, and had his questioner urinate into his pried-open mouth.[20] Rákosi thereafter imposed totalitarian rule on Hungary. At the height of his rule, Rákosi developed a strong cult of personality.[21] Dubbed the "bald murderer", Rákosi imitated Stalinist political and economic programs, resulting in Hungary experiencing one of the harshest dictatorships in Europe.[22][23] He described himself as "Stalin's best Hungarian disciple"[21] and "Stalin's best pupil".[24]

.svg.png)

The government collectivized agriculture and it extracted profits from the country's farms to finance rapid expansion of heavy industry, which attracted more than 90% of total industrial investment. At first Hungary concentrated on producing primarily the same assortment of goods it had produced before the war, including locomotives and railroad cars. Despite its poor resource base and its favorable opportunities to specialize in other forms of production, Hungary developed new heavy industry in order to bolster further domestic growth and produce exports to pay for raw-material import.

Rákosi rapidly expanded the education system in Hungary. This was mostly in attempt to replace the educated class of the past by what Rákosi called a new "working intelligentsia". In addition to some beneficial effects such as better education for the poor, more opportunities for working-class children and increased literacy in general, this measure also included the dissemination of communist ideology in schools and universities. Also, as part of an effort to separate the Church from the State, religious instruction was denounced as propaganda and was gradually eliminated from schools.

Cardinal József Mindszenty, who had opposed the German Nazis and the Hungarian Fascists during the Second World War, was arrested in December 1948 and accused of treason. After five weeks under arrest, he confessed to the charges made against him and he was condemned to life imprisonment. The Protestant churches were also purged and their leaders were replaced by those willing to remain loyal to Rákosi's government.

The new Hungarian military hastily staged public, prearranged trials to purge "Nazi remnants and imperialist saboteurs". Several officers were sentenced to death and executed in 1951, including Lajos Tóth, a 28 victory-scoring flying ace of the World War II Royal Hungarian Air Force, who had voluntarily returned from US captivity to help revive Hungarian aviation. The victims were cleared posthumously following the fall of communism.

Rákosi grossly mismanaged the economy and the people of Hungary saw living standards fall rapidly. His government became increasingly unpopular, and when Joseph Stalin died in 1953, Mátyás Rákosi was replaced as prime minister by Imre Nagy. However, he retained his position as general secretary of the Hungarian Working People's Party and over the next three years the two men became involved in a bitter struggle for power.

As Hungary's new leader, Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on changes to the political system and liberalizing the economy. This included a promise to increase the production and distribution of consumer goods. Nagy also released political prisoners from Rákosi's numerous purges of the Party and society.

On 9 March 1955, the Central Committee of the Hungarian Working People's Party condemned Nagy for rightist deviation. Hungarian newspapers joined the attacks and Nagy was accused of being responsible for the country's economic problems and on 18 April he was dismissed from his post by a unanimous vote of the National Assembly. Rákosi once again became the leader of Hungary.

Rákosi's power was undermined by a speech made by Nikita Khrushchev in February 1956. He denounced the policies of Joseph Stalin and his followers in Eastern Europe. He also claimed that the trial of László Rajk had been a "miscarriage of justice". On 18 July 1956, Rákosi was forced from power as a result of orders from the Soviet Union. However, he did manage to secure the appointment of his close friend, Ernő Gerő, as his successor.

On 3 October 1956, the Central Committee of the Hungarian Working People's Party announced that it had decided that László Rajk, György Pálffy, Tibor Szőnyi and András Szalai had wrongly been convicted of treason in 1949. At the same time it was announced that Imre Nagy had been reinstated as a member of the party.

Revolution of 1956

.svg.png)

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 began on 23 October as a peaceful demonstration of students in Budapest. The students protested for the implementation of several demands including an end to Soviet occupation. The police made some arrests and tried to disperse the crowd with tear gas. When the protesters attempted to free those who had been arrested, the police opened fire on the crowd, provoking rioting throughout the capital.

Early the following morning, Soviet military units entered Budapest and seized key positions. Citizens and soldiers joined the protesters chanting "Russians go home" and defacing communist party symbols. The Central Committee of the Hungarian Working People's Party responded to the pressure by appointing the reformer Imre Nagy as the new Prime Minister.

On 25 October, a mass of protesters gathered in front of the Parliament Building. ÁVH units began shooting into the crowd from the rooftops of neighboring buildings.[25]

Some Soviet soldiers returned fire on the ÁVH, mistakenly believing that they were the targets of the shooting.[26] Supplied by arms taken from the ÁVH or given by Hungarian soldiers who joined the uprising, some in the crowd started shooting back.[25][26]

Imre Nagy now went on Radio Kossuth and announced he had taken over the leadership of the Government as Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the People's Republic of Hungary. He also promised "the far-reaching democratization of Hungarian public life, the realisation of a Hungarian road to socialism in accord with our own national characteristics, and the realisation of our lofty national aim: the radical improvement of the workers' living conditions."

On 28 October, Nagy and a group of his supporters, including János Kádár, Géza Losonczy, Antal Apró, Károly Kiss, Ferenc Münnich and Zoltán Szabó, managed to take control of the Hungarian Working People's Party. At the same time revolutionary workers' councils and local national committees were formed all over Hungary.

The change of leadership in the party was reflected in the articles of the government newspaper, Szabad Nép (i.e. Free People). On 29 October the newspaper welcomed the new government and openly criticised Soviet attempts to influence the political situation in Hungary. This view was supported by Radio Miskolc that called for the immediate withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country.

On 30 October, Imre Nagy announced that he was freeing Cardinal József Mindszenty and other political prisoners. He also informed the people that his government intended to abolish the one-party state. This was followed by statements of Zoltán Tildy, Anna Kéthly and Ferenc Farkas concerning the restitution of the Smallholders Party, the Social Democratic Party and the Petőfi (former Peasants) Party.

Nagy's most controversial decision took place on 1 November when he announced that Hungary intended to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact and proclaim Hungarian neutrality. He asked the United Nations to become involved in the country's dispute with the Soviet Union.

On 3 November, Nagy announced the details of his coalition government. It included communists (János Kádár, Georg Lukács, Géza Losonczy), three members of the Smallholders Party (Zoltán Tildy, Béla Kovács and István Szabó), three Social Democrats (Anna Kéthly, Gyula Keleman, Joseph Fischer), and two Petőfi Peasants (István Bibó and Ferenc Farkas). Pál Maléter was appointed minister of defence.

Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Soviet Union, became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4 November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. Soviet tanks immediately captured Hungary's airfields, highway junctions and bridges. Fighting took place all over the country but the Hungarian forces were quickly defeated.

During the Hungarian Uprising, an estimated 20,000 people were killed, nearly all during the Soviet intervention. Imre Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, János Kádár, as head of the newly formed Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party (Magyar Szocialista Munkáspárt). Nagy was imprisoned until being executed in 1958. Other government ministers or supporters who were either executed or died in captivity included Pál Maléter, Géza Losonczy, Attila Szigethy and Miklós Gimes.

Changes under Kádár

First Kádár followed retributions against the revolutionaries. 21,600 dissidents were imprisoned, 13,000 interned, and 400 executed. But in the early 1960s, he announced a new policy under the motto "He who is not against us is with us", a variation of Rákosi's quote: "He who is not with us is against us". He declared a general amnesty, gradually curbed some of the excesses of the secret police, and introduced a relatively liberal cultural and economic course aimed at overcoming the post-1956 hostility towards him and his regime. Homosexuality was decriminalized in 1961.[27]

In 1966, the Central Committee approved the "New Economic Mechanism", which moved away from a strictly planned economy towards a system more reminiscent of the decentralized Yugoslav model. Over the next two decades of relative domestic quiet, Kádár's government responded alternately to pressures for minor political and economic reforms as well as to counter-pressures from reform opponents. Dissidents (the so-called ''Democratic Opposition'' (Hu: Demokratikus ellenzék) still remained closely watched by the secret police however, particularly during the anniversaries of the 1956 uprising in 1966, 1976, and 1986.

By the early 1980s, it had achieved some lasting economic reforms and limited political liberalization and pursued a foreign policy which encouraged more trade with the West. Nevertheless, the New Economic Mechanism led to mounting foreign debt, incurred to subsidize unprofitable industries. Many of Hungary's manufacturing facilities were outmoded and unable to produce goods that were salable on world markets. Despite this, they succeeded in obtaining sizable financial loans from Western countries without much difficulty. During a 1983 visit to Hungary, Soviet leader Yuri Andropov expressed interest in adopting some of the country's economic reforms in the Soviet Union.

Hungary remained committed to a pro-Soviet foreign policy and openly criticized US president Ronald Reagan's deployment of intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Europe. In a speech to the CPH's youth organization in 1981, Kádár said "The forces of capitalism are trying to distract attention from their mounting social problems by stepping up the arms race, but there can be no prospect for mankind other than that of peace and social progress." In 1983, Vice President George H.W. Bush and the foreign ministers of France and West Germany visited Budapest, where they received a friendly welcome, but the Hungarian leadership nonetheless reiterated their opposition to US missile deployment. They also cautioned the Western representatives to not mistake Hungary's economic reforms for a sign that the country would embrace capitalism.

Other events during Kadar's tenure were Hungarian aid and support of North Vietnam during the Vietnam War, severing relations with Israel following the Six-Day War, and the boycott of the 1984 Summer Olympics during the Soviet conflict in Afghanistan.[28]

Transition to liberal democracy

The rise of Mikhail Gorbachev to power in the Soviet Union in 1985 had changed course for its foreign policy. Hungary's transition to a Western-style democracy was one of the smoothest among the former Soviet bloc. By late 1988, activists within the party and bureaucracy and Budapest-based intellectuals were increasing pressure for change. Some of these became reformist social democrats, while others began movements which were to develop into parties. Young liberals formed the Federation of Young Democrats (Fidesz). A core from the so-called Democratic Opposition formed the Association of Free Democrats (SZDSZ) and the national opposition established the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF). Nationalist movements, such as the Jobbik, only reappeared after a rapid decline in nationalist sentiment following the establishment of the new Republic. Civic activism intensified to a level not seen since the 1956 revolution.

In 1988, Kádár was replaced as General Secretary of the MSZMP by Prime Minister Károly Grósz, and reform communist leader Imre Pozsgay was admitted to the Politburo. In 1989, the Parliament adopted a "democracy package", which included trade union pluralism; freedom of association, assembly, and the press; and a new electoral law; and in October 1989 a radical revision of the constitution, among others. A Central Committee plenum in February 1989 endorsed in principle the multiparty political system and the characterization of the October 1956 revolution as a "popular uprising", in the words of Pozsgay, whose reform movement had been gathering strength as Communist Party membership declined dramatically. Kádár's major political rivals then cooperated to move the country gradually to Western-style democracy. The Soviet Union reduced its involvement by signing an agreement in April 1989 to withdraw Soviet forces by June 1991.

While Grósz favoured reforming and refining the system, the "democracy package" and constitutional revisions went well beyond the "model change" he advocated–i.e., changing the system within the framework of Communism. However, Grósz was rapidly eclipsed by a faction of radical reformers including Pozsgay, Miklós Németh (who succeeded Grósz as prime minister later in 1988), Foreign Minister Gyula Horn, and Rezső Nyers. This faction now favoured jettisoning Communism altogether in favour of a market economy. By the summer of 1989, it was clear that the HSWP was no longer a Marxist-Leninist party. In June, a four-man executive presidency replaced the Politburo. Three of its four members came from the radical reform faction, including Nyers, who became party president. Grósz retained his title of general secretary, but Nyers now outranked him–effectively making him the leader of Hungary.

National unity culminated in June 1989 as the country reburied Imre Nagy, his associates, and, symbolically, all other victims of the 1956 revolution. A national round table, comprising representatives of the new parties, some recreated old parties (such as the Smallholders and Social Democrats), and different social groups, met in the late summer of 1989 to discuss major changes to the Hungarian constitution in preparation for free elections and the transition to a fully free and democratic political system.

In October 1989, the Communist Party convened its last congress and re-established itself as the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), with Nyers as its first president. In a historic session on 16–20 October 1989, the Parliament adopted a package of nearly 100 constitutional amendments that almost completely rewrote the 1949 constitution. The amendments–the first comprehensive constitutional reform in the Soviet bloc–changed Hungary's official name to the Republic of Hungary, guaranteed human and civil rights, and created an institutional structure that ensured separation of powers among the judicial, executive, and legislative branches of government. The revised constitution also championed the "values of bourgeois democracy and democratic socialism" and gave equal status to public and private property. On the 33rd anniversary of the 1956 Revolution, 23 October, the Presidential Council was dissolved. In accordance with the constitution, parliament Speaker Mátyás Szűrös was named provisional president pending elections the following year. One of Szűrös' first acts was to officially proclaim the Republic of Hungary.

Hungary decentralized its economy and strengthened its ties with western Europe; in May 2004 Hungary became a member of the European Union.

Economy

As a member of the Eastern Bloc, initially, Hungary was shaped by various directives of Joseph Stalin that served to undermine Western institutional characteristics of market economies, democratic governance (dubbed "bourgeois democracy" in Soviet parlance), and the rule of law subduing discretional intervention by the state.[29] The Soviets modeled economies in the rest of the Eastern Bloc, such as Hungary, along Soviet command economy lines.[30] Economic activity was governed by Five Year Plans, divided into monthly segments, with government planners frequently attempting to meet plan targets regardless of whether a market existed for the goods being produced.[31]

Producer goods were favored over consumer goods, causing consumer goods to be lacking in quantity and quality in the shortage economies that resulted.[32] Overall, the inefficiency of systems without competition or market-clearing prices became costly and unsustainable, especially with the increasing complexity of world economics.[33] Meanwhile, other Western European nations experienced increased economic growth in the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle"), Trente Glorieuses ("thirty glorious years"), and the post-World War II boom.

While most western European economies essentially began to approach the per capita Gross Domestic Product levels of the United States, Hungary's did not,[34] with its per capita GDPs falling significantly below their comparable western European counterparts:[35]

| Per Capita GDP (1990 $) | 1938 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | $1,800 | $19,200 |

| Czechoslovakia | $1,800 | $3,100 |

| Finland | $1,800 | $26,100 |

| Italy | $1,300 | $16,800 |

| Hungary | $1,100 | $2,800 |

| Poland | $1,000 | $1,700 |

| Spain | $900 | $10,900 |

The per capita GDP figures are similar when calculated on PPP basis:[36]

| Per Capita GDP (1990 $) | 1950 | 1973 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | $3,706 | $11,235 | $16,881 |

| Italy | $3,502 | $10,643 | $16,320 |

| Czechoslovakia | $3,501 | $7,041 | $8,895(Czech Lands)/ $7,762(Slovakia) |

| Soviet Union | $2,834 | $6,058 | $6,871 |

| Hungary | $2,480 | $5,596 | $6,471 |

| Spain | $2,397 | $8,739 | $12,210 |

As shown above, the GDP per capita of Hungary, and the Eastern Bloc as a whole, lagged behind that of Capitalist Western Europe. However, Capitalist Western Europe got a significant amount of aid (billions of US Dollars) in the Marshall Plan from the United States, whose economy was largely unaffected by World War II. When Hungary is compared to Capitalist Latin America, a part of the world that did not get significant aid, we see Hungary perform better, as the graph below demonstrates:[37]

| GDP per capita in International 1990 Geary-Khamis Dollars | 1938 | 1945 | 1949 | 1955 | 1970 | 1990 | 2003 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Europe | $4398 | $3806 | $4319 | $5740 | $10,195 | $15,965 | $19,912 |

| Hungary | $2543 | No data | $2354 | $3070 | $5028 | $6459 | $7947 |

| Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, México, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela | $2108 | $2304 | $2682 | $3026 | $4309 | $5465 | $6278 |

Housing shortages emerged.[38] The near-total emphasis on large low quality prefabricated apartment blocks, such as Hungarian Panelház, was a common feature of Eastern Bloc cities in the 1970s and 1980s.[39] Even by the late 1980s, sanitary conditions were generally far from adequate.[40] Only 60% of Hungarian housing had adequate sanitation by 1984, with only 36% of housing having piped water.[41]

Notes

- Rao, B. V. (2006), History of Modern Europe A.D. 1789–2002, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Gati, Charles (September 2006). Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt. Stanford University Press. p. 47–49. ISBN 0-8047-5606-6.

- Élesztős, László, ed. (2004). "Magyarország határai" [Borders of Hungary]. Révai új lexikona (in Hungarian). 13. Szekszárd: Babits Kiadó. p. 895. ISBN 963-9556-13-0.

- "Az 1990. évi népszámlálás előzetes adatai". Statisztikai Szemle. 68 (10): 750. October 1990.

- "1949. évi XX. törvény. A Magyar Népköztársaság Alkotmánya" [Act XX of 1949. The Constitution of the Hungarian People's Republic]. Magyar Közlöny (in Hungarian). Budapest: Állami Lapkiadó Nemzeti Vállalat. 4 (174): 1361. 20 August 1949.

- "1989. évi XXXI. törvény az Alkotmány módosításáról" [Act XXXI of 1989 on the Amendment of the Constitution]. Magyar Közlöny (in Hungarian). Budapest: Pallas Lap- és Könyvkiadó Vállalat. 44 (74): 1219. 23 October 1989.

- Melvyn Leffler, Cambridge History of the Cold War: Volume 1 (Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 175

- The Untold History of the United States, Stone, Oliver and Kuznick, Peter (Gallery Books, 2012), p. 114, citing The Second World War Triumph and Tragedy, Churchill, Winston, 1953, pp. 227–228, and Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Nineties, Johnson, Paul (New York: Perennial, 2001), p. 434

- Hungary: a country study. Library of Congress Federal Research Division, December 1989.

- Crampton 1997, p. 241.

- Nyyssönen, Heino (1 June 2006). "Salami reconstructed". Cahiers du monde russe. 47 (1–2): 153–172. doi:10.4000/monderusse.3793. ISSN 1252-6576.

- Wettig 2008, p. 51.

- Wettig 2008, p. 85.

- Norton, Donald H. (2002). Essentials of European History: 1935 to the Present, p. 47. REA: Piscataway, New Jersey. ISBN 0-87891-711-X.

- UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II.N, para 89(xi) (p. 31)" (PDF). (1.47 MiB)

- "The Untold History of the United States," Stone, Oliver and Kuznick, Peter, Gallery Books 2012, p. 208, citing Gardner, Lloyd C., "Architects of Illusion: Men and Ideas in American Foreign Policy, 1941–1949," p. 221, and Ann O'Hare McCormick, "Open Moves in the Political War for Europe," New York Times, 2 June 1947

- Wettig 2008, p. 110.

- Kontler, László. A History of Hungary. Palgrave Macmillan (2002), ISBN 1-4039-0316-6

- Crampton 1997, p. 263

- Crampton 1997, p. 264.

- Sugar, Peter F., Peter Hanak and Tibor Frank, A History of Hungary, Indiana University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-253-20867-X, pp. 375–377

- Granville, Johanna, The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956, Texas A&M University Press, 2004. ISBN 1-58544-298-4

- Gati, Charles, Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest, and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt, Stanford University Press, 2006 ISBN 0-8047-5606-6, pp. 9–12

- Matthews, John P. C., Explosion: The Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Hippocrene Books, 2007, ISBN 0-7818-1174-0, pp. 93–94

- UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter X.I, para 482 (p. 153)" (PDF). (1.47 MiB)

- UN General Assembly Special Committee on the Problem of Hungary (1957) "Chapter II.F, para 64 (p. 22)" (PDF). (1.47 MiB)

- "Homosexualité communiste 1945-1989 (Créteil)".

- "Hungary Joins Soviet In Quitting Olympics". New York Times. 17 May 1984. p. A15. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 12.

- Turnock 1997, p. 23.

- Crampton 1997, p. 250.

- Dale 2005, p. 85.

- Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 1.

- Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 16.

- Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 17.

- Maddison 2006, p. 185.

- Maddison, Angus, Historical Statistics for the World Economy, 2003 – available at www.ggdc.net/maddison/Historical_Statistics/horizontal-file_03-2007.xls

- Sillince 1990, pp. 11–12.

- Turnock 1997, p. 54.

- Sillince 1990, p. 18.

- Sillince 1990, pp. 19–20.

References

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (2007), A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-36626-7

- Crampton, R. J. (1997), Eastern Europe in the twentieth century and after, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-16422-2

- Dale, Gareth (2005), Popular Protest in East Germany, 1945-1989: Judgements on the Street, Routledge, ISBN 0714654086

- Hardt, John Pearce; Kaufman, Richard F. (1995), East-Central European Economies in Transition, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-612-0

- Maddison, Angus (2006). The world economy. OECD Publishing. ISBN 92-64-02261-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sillince, John (1990), Housing policies in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-02134-0

- Turnock, David (1997), The East European economy in context: communism and transition, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-08626-4

- Wettig, Gerhard (2008), Stalin and the Cold War in Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-7425-5542-6

External links

- Everyday communism – on life, books and women in communist Hungary, Hungary Review

- History of the Revolutionary Workers Movement in Hungary: 1944–1962, an English-language Hungarian work published in 1972.

- The CWIHP at the Woodrow Wilson Center for Scholars Collection on Hungary in the Cold War

.svg.png)