Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall

Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall is a group of historic buildings in Plymouth Meeting, Whitemarsh Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. In the decades prior to the American Civil War, the property served as an important station on the Underground Railroad. Abolition Hall was built to be a meeting place for abolitionists, and later was the studio of artist Thomas Hovenden.

Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall | |

Maulsby-Corson-Hovenden House, built c.1795. | |

| |

| Location | 1 E. Germantown Pike, Plymouth Meeting, Whitemarsh Township, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°6′10″N 75°16′41″W |

| Area | 9 acres (3.6 ha) |

| Built | c.1795, 1856 |

| Built by | Samuel Maulsby (house & barn) George Corson (Abolition Hall) |

| Architectural style | Federal |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000713[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | February 18, 1971 |

| Designated PHMC | November 18, 2000[2] |

The house is located at the northeast corner of Germantown and Butler Pikes, diagonally opposite the Plymouth Friends Meetinghouse. Northeast of the house is the stone barn, and attached to the barn's northeast corner is the 2-story carriage house known as Abolition Hall. The three buildings are part of a 10.45-acre farm, and are contributing properties in the Plymouth Meeting Historic District.[3]

The property is threatened by a 2016 proposal to reroute Butler Pike between the Hovenden House and its barn. Preservation Pennsylvania added the property to its 2017 Pennsylvania At Risk list.[4][5]

History

The settlement at Plymouth Meeting was founded by a group of Devonshire Quakers who arrived in Pennsylvania in 1686. The Maulsby family, who later attained prominence, arrived in Pennsylvania in 1698, and came to Whitemarsh Township in 1705.[6]

Maulsby

Merchant Maulsby Jr. (1737–1772) was a millwright, who married Hannah Davis (1743–1807) in 1766.[6] On June 20, 1767, he purchased a 100-acre farm with frontage on the "Whitemarsh great road" (Germantown Pike) and the "Plymouth line" (Butler Pike), for £651.[lower-alpha 1] The purchase did not include the 8.25-acre plot at the northeast corner of Germantown and Butler Pikes, which the 1767 deed described as "Elizabeth and Catherine Ellis's Land."[7] He and his wife built a 2-story stone house on the property.[lower-alpha 2] They had two children – Samuel (1768–1838)[8] and Elizabeth (married John Freese).[6] In 1769, Merchant Jr. was taxed £10 on 100 acres, one horse and one cow.[9] He died in February 1772 at age 34.[10]

In the early morning of May 20, 1778, 10-year-old Samuel Maulsby watched as British troops marched down Butler Pike to the meetinghouse, part of their unsuccessful attempt to surround the Marquis de Lafayette and 2,100 Continental troops at the Battle of Barren Hill.[11] Maulsby's recollections were recorded by John Fanning Watson in his Annals of Philadelphia (1830), including his description of Redcoats looting his widowed mother's house.[12]

Widow Hannah Davis Maulsby married David Marple in 1781, and was soon widowed again.[10] She married Richard Corson in 1784, with whom she had two children, Richard and Hannah.[10] The Corsons occupied her 2-story stone house for a time, but settled in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.[13] Samuel Dean was farming the Maulsby property in 1781; Enoch Marple was farming it in 1783; and seventeen-year-old Samuel Maulsby and his former schoolmate Joseph Corson, a nephew of Richard Corson,[13] were farming it in 1785.[6] Joseph Corson married Hannah Dickinson in 1786, and the young couple rented the 2-story stone house until 1789.[13] Like Samuel Maulsby, they became abolitionists, and decades later one of their sons would marry one of his daughters.[13]

On 3 February 1794, Samuel Maulsby purchased the 8.25-acre plot at the northeast corner of Germantown and Butler Pikes, for £137.[14] The sellers were John Fontiles and his wife Elizabeth, who had bought the corner plot from Joseph and Mary Potts on February 2, 1789.[14] The 1794 deed mentioned "a messuage" (house) on the property, but did not describe it.[14] Maulsby later purchased adjacent plots at the north end of the farm, which expanded it to 128 acres (51.8 hectares) and extended it to Flourtown Road.[6]

Samuel Maulsby was the owner of a large and fertile farm at Plymouth Meeting... It included the whole north east corner of the two roads, the Germantown turnpike, its south boundary, and the Plymouth and Broad Axe turnpike, along which it extended for half a mile, its western boundary. [I]n addition to the farming operations the burning of lime[lower-alpha 3] was extensively carried on by him.[13]

About 1795, he built a 3-story, 14-room, Federal-style dwelling on the corner, diagonally opposite the meetinghouse.[3] An earlier stone house seems to have been incorporated into his new house.[lower-alpha 4] Maulsby built the stone barn, perhaps around the same time,[15] and is presumed to have built the carriage shed.[3] In 1799, he married Susanna Thomas (1780–1818),[10] and they had seven children.[16]

Maulsby built or altered the Cater Corner House (c.1802), at the southeast corner of Butler Pike and Flourtown Road, possibly as housing for Thomas Davis, a free-black limeburner recorded as living on his property.[11] At 3-5 Germantown Pike, just east of his house, Maulsby built the Plymouth Meeting General Store and Post Office (c.1826-27). His son Jonathan (1801–1845) ran the store and served as Plymouth Meeting's first postmaster.[17]

In 1832, Maulsby's daughter Martha (1807–1870) married George Corson (1803-1860), a son of Joseph and Hannah Corson, and a former clerk in the general store.[13] Samuel Maulsby died on July 12, 1838, and was interred beside his wife in the meetinghouse's burial ground.[6] George and Martha Maulsby Corson purchased the farm from his estate on April 6, 1839.[18] George and his brothers purchased the Maulsby limestone quarries, and founded what became G. & W. H. Corson Company - Lime Merchants.[19]

Abolitionism

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 made it a federal crime to give assistance to an escaped slave.

The earliest and only abolitionists in Plymouth and Whitemarsh townships were Samuel Maulsby, Joseph Corson and [his son] Alan W. Corson. Away back before 1820 they had been stirred by the scathing denunciations of slavery, and the horrors of the slave trade, made by Granville Sharp, William Wilberforce and Thomas Fouell Buxton, before the Parliament of Great Britain, to an intense hatred of slavery and the slave trade, and the abominations of slavery in our own country.[20]

Maulsby and the Corsons co-founded the Plymouth Meeting Anti-Slavery Society in 1831, which initially had seven members and met at the Plymouth Friends Meeting House. They also co-founded the Montgomery County Anti-Slavery Society in 1837, which initially had about twenty members and met at various locations in Norristown.[21] Frederick Douglass, former-slave and abolitionist, was the keynote speaker at an August 1847 anti-slavery convention held at the First Baptist Church of Norristown.[21] His lecture was disrupted by about sixty ruffians standing outside and pelting the church's windows with rocks.[21] A plot to abduct and lynch Douglass was thwarted.[22]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

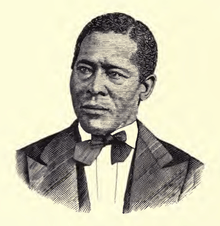

Both George Corson's and Martha Maulsby's parents had sheltered escaped slaves.[13] But it was the couple's close friendship with Benjamin Lundy – publisher of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society's weekly newspaper, The National Enquirer (1836–38) – that inspired them to fully engage in the cause.[13] They turned their property into a major station on the Underground Railroad,[lower-alpha 5] providing food and shelter to hundreds of escaped slaves.[24] Daniel Ross, a free black man in Norristown, Pennsylvania, often acted as "conductor,"[25] leading the fugitives by night to the next station[26] — north to the house of William Foulke at Penllyn, Pennsylvania; or northeast to abolitionists living around the Quaker meetinghouses in Upper Dublin[27] and Horsham, Pennsylvania.[28] The Underground Railroad route continued through Bucks County, New Jersey and New York, and to eventual freedom in Canada.[29] In at least one instance, Corson hid people under a wagonload of hay and drove them to the next station.[3]

The greater burden of the work [of sheltering runaways] was borne by George and his wife, Martha Maulsby Corson. Their residence in the old Maulsby home, right in front of the Friends' Plymouth Meeting-House, was so prominent a place, known by everybody for miles around, made it easy for slaves to find the place, when sent by those from a distance to "George Corson's at Plymouth Meeting." He it was who forwarded fugitives to Mahlon Linton, at Newtown, or to William H. Johnson, at Buckingham, or to Richard Moore, at Quakertown, Bucks county, time after time, during the whole period of the great struggle from 1830 to 1850.[20]

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increased the penalties for giving assistance to an escaped slave to six months in prison and a $1,000 fine. It allowed slavecatchers to pursue a fugitive across state lines into every U.S. state and territory. Corson was involved in hiding Jane Johnson, whose escape exposed a loophole in the federal law.[30]

George Corson, who knew no fear when in the right. — The Abolitionists of Montgomery County (1900)[20]

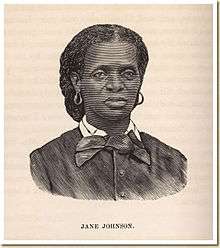

Jane Johnson

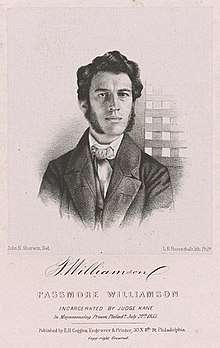

On the morning of July 18, 1855, Jane Johnson (c.1822–1872) and her two young sons, Daniel and Isaiah, arrived in Philadelphia by train with their master, North Carolina slaveholder John H. Wheeler, and his wife and three children.[31] Wheeler was U.S. Ambassador to Nicaragua, and they were en route from Washington, D.C. to New York City, from which they would board a ship to return to Central America. At Philadelphia, they had to switch to a ferry to cross the Delaware River. Wheeler locked Johnson and her sons in a hotel room while he and his family took the afternoon to tour the city. Pennsylvania had begun an abolition of slavery in 1780, completed in 1847, and did not recognize the property rights of any slaveholder. Johnson sought help from a hotel porter in escaping to freedom.[30] The porter contacted abolitionist William Still, the son of former slaves, and Still and lawyer Passmore Williamson rushed to the docks as the 5:00 pm ferry was about to depart for Camden, New Jersey. They found Johnson and her sons with their master on the ferry's upper deck. Williamson approached her and explained that Pennsylvania law guaranteed her freedom, if she chose it:[30]

"You are entitled to your freedom according to the laws of Pennsylvania, having been brought into the State by your owner. If you prefer freedom to slavery, as we suppose everybody does, you have the chance to accept it now. Act calmly—don't be frightened by your master—you are as much entitled to your freedom as we are, or as he is—be determined and you need have no fears but that you will be protected by the law. Judges have time and again decided cases in this city and State similar to yours in favor of freedom! Of course, if you want to remain a slave with your master, we cannot force you to leave; we only want to make you sensible of your rights. Remember, if you lose this chance you may never get such another ..."

During the few moments in which the above remarks were made, the slaveholder frequently interrupted—said she understood all about the laws making her free, and her right to leave if she wanted to; but contended that she did not want to leave— ... [B]ut the woman's desire to be free was altogether too strong to allow her to make a single acknowledgment favorable to his wishes in the matter. On the contrary, she repeatedly said, distinctly and firmly, "I am not free, but I want my freedom—ALWAYS wanted to be free!! but he holds me."

The [ferry's] last bell tolled! The last moment for further delay passed! The arm of the woman being slightly touched, accompanied with the word, "Come!" she instantly arose. Instantly on their starting, the slave-holder rushed at the woman and her children, to prevent their leaving; and, if I am not mistaken, he simultaneously took hold of the woman and Mr. Williamson, which resistance on his part caused Mr. W. to take hold of him and set him aside quickly. The passengers were looking on all around, but none interfered in behalf of the slaveholder except one man, whom I took to be another slaveholder. He said harshly, "Let them alone; they are his property!" The woman and children were assisted, but not forced to leave. Nor were there any violence or threatenings as I saw or heard.[32]:88–89

As Still led Johnson and her sons away, five black dockhands prevented Wheeler from stopping them.[lower-alpha 6] Williamson remained to explain to authorities that this had been a lawful act, not a kidnapping.[30]

Williamson, the only white man involved, was arrested and charged with violating the Fugitive Slave Act.[lower-alpha 7] Federal Judge John Kintzing Kane presided over his trial, and refused to believe that Williamson did not know where Johnson was being hidden. Kane found him in contempt of court, and jailed him for more than three months, which attracted national attention.[33] Williamson's successful defense was that Johnson's master had brought her into Pennsylvania, a free state, therefore she was not a fugitive across state lines, and state law rather than federal law applied.[34] Still and the five dockhands were charged with forcible abduction, rioting, disorderly conduct, and assault. On August 29, 1855, Johnson appeared as a surprise witness at their trial, and testified that she had voluntarily walked away from Wheeler. The most serious charges against the men were dismissed, although the two who had restrained Wheeler were convicted of assault and spent a week in jail.[30] Johnson was escorted out of the courthouse by Lucretia Mott, Rev. James Miller McKim and George Corson.[32]:96 She was hidden at Corson's house in Plymouth Meeting to prevent pro-slavery activists from abducting her and returning her to slavery.[lower-alpha 8] At the end of her stay, Corson's 13-year-old son, Ellwood, drove Johnson in a carriage by night to Mahlon Linton's house in Newtown, Pennsylvania.[33][35] From there she was smuggled to Boston, Massachusetts and reunited with her sons.[30]

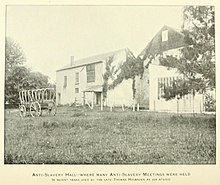

Abolition Hall

The Jane Johnson affair caused a national controversy—largely cheered in the North, viciously condemned in the South.[30] The Plymouth Friends Meeting had permitted the anti-slavery society to use its meeting house for more than two decades,[36] but, following the suspicious burning of a church that had hosted abolitionist speakers, in 1856 permission was denied for the first time.[37] George Corson's reaction was to built a lecture hall above his carriage shed to provide a space for abolitionist meetings.

He determined to build a hall, over which he could have control. He made quite a large one and furnished it well with seats, warmed and lighted at his own expense. And now we can see how convenient it was for the lecturers to make his house their temporary home. As time wore on more and more neighbors and friends were attracted to the meetings to hear the eloquent and earnest men and women who pictured the atrocities of slavery.[36]

Abolition Hall could hold up to 200 people,[26] and provided a meeting hall for the Plymouth Meeting Anti-Slavery Society and for lectures by prominent abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass,[38] Harriet Beecher Stowe, William Lloyd Garrison and Lucretia Mott.[39]

Corson died in November 1860. William Still eulogized Corson in his 1872 history of the Underground Railroad:

There were perhaps few more devoted men than George Corson to the interests of the oppressed everywhere. The slave, fleeing from his master, ever found a home with him, and felt while there that no slave-hunter would get him away until every means of protection should fail. He was ever ready to send his horse and carriage to convey them on the road to Canada, or elsewhere toward freedom. His home was always open to entertain the anti-slavery advocates, and being warmly supported in the cause by his excellent wife, everything which they could do to make their guests comfortable was done. It is to be regretted that he died before the emancipation of the slaves, which he had so long labored for, arrived.[40]

Artist's studio

The Corsons' daughter Helen (1846-1935), trained as an artist at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. She further studied in Paris, and exhibited at the Paris Salon, 1876, 1879 and 1880.[41] She met Irish-born painter Thomas Hovenden (1840-1895) in France, and they were married at the Plymouth Friends Meeting House on June 9, 1881.[13] They moved into her late parents' house, and raised two children, Thomas Jr. and Martha.

Hovenden succeeded Thomas Eakins as Professor of Painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1886.[42] He specialized in genre scenes of rural life, using his neighbors, often African Americans, as models.[26] He converted Abolition Hall into a studio,[3] and the moral causes that had been championed there inspired some of his works.[43] His most famous painting – The Last Moments of John Brown (1882–84), Metropolitan Museum of Art – depicts the radical abolitionist John Brown kissing a baby as he is led to the gallows. Hovenden was elected a member of the National Academy of Design in 1881, and an academician in 1882.[42]

"Thomas Hovenden lost his life on an unguarded grade crossing of the Pennsylvania Railroad near his home, August 14, 1895, in an attempt to save the life of a little girl who was crossing in front of an approaching engine. Both were killed."[44] The accident occurred about three miles from his house, near the south end of what is now Chemical Road. Helen Corson Hovenden's advocacy pressured the Pennsylvania Railroad into elevating the tracks of its high-speed Trenton Cutoff, separating them from the grade level tracks of trolleys. Rev. William Henry Furness gave the eulogy at Thomas Hovenden's funeral, and Eakins and sculptor Samuel Murray were among the pall bearers.[45]

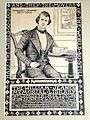

Helen Corson Hovenden was noted for her portraits of children and pets.[46] The couple's daughter, Martha Maulsby Hovenden (1884-1941), a sculptor who trained at PAFA under Charles Grafly and at the Art Students League of New York under Hermon Atkins MacNeil,[47] later used Abolition Hall as her studio.[13] Examples of her work can be seen at the Washington Memorial Chapel in Valley Forge. In 1939, she designed a bookplate, which is still in use by the Friends of the William Jeanes Memorial Library. In October 2016, the Friends of the Library donated the original etched copper printing plate to the Woodmere Art Museum in nearby Chestnut Hill.

Nancy Corson (1920-2012), a great-granddaughter of George Corson and granddaughter of Dr. Ellwood M. Corson (the teenager who had assisted Jane Johnson in 1855), made the Maulsby stone barn her residence from 1946 until her death in 2012.

Plymouth Meeting Historic District

The village of Plymouth Meeting was designated a Pennsylvania historic district in 1961, by a joint resolution of Plymouth and Whitemarsh Townships. The district encompassed 66 historic structures.

In 1971, the village of Plymouth Meeting became Pennsylvania's first National Register District.[48] At the time, the Maulsby/Corson/Hovenden homestead was threatened by a plan to split Butler Pike into two one-way highways that would straddle the buildings on the property. The northbound bypass would have run alongside the east wall of the barn, and required the demolition of Abolition Hall. Nancy Corson authored a separate NRHP nomination specifically for the Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall as a unit, which was also approved in 1971.[3] Plans for the bypass were abandoned.

Historical marker

Nancy Corson and Charles L. Blockson, an authority on the history of the Underground Railroad, co-wrote the nomination for a Pennsylvania state historical marker to commemorate Abolition Hall. The marker was approved, and dedicated at 4006 Butler Pike (in front of the barn) on November 18, 2000:[49]

Recent history

An offer by Whitemarsh Township to purchase the property for open space was declined by its owners in 2014.[50]

Proposed development

In late 2015, K. Hovnanian Builders submitted a sketch plan to the township's planning/zoning office that proposed the construction of 48 townhouses on the eight acres of open space behind the buildings.[51] The plan included the re-routing of Butler Pike between the Hovenden House and the Barn/Abolition Hall.[52] This re-routing would require the demolition or relocation of the Plymouth Meeting General Store and Post Office (also listed on the National Register).[48]

Following vocal opposition, the Whitemarsh Township Board of Supervisors unanimously voted to deny the request for a zoning variance. In response, the developer requested a continuance of a scheduled April 25, 2016 zoning hearing.[53] In late August 2016, K. Hovnanian Builders submitted a revised Zoning Plan to Whitemarsh Township, asserting that this plan met the requirements for shared parking and access (with an adjacent property). In early November 2016, the Zoning Officer issued his Preliminary Opinion, concurring with the developer's assertion that the current Zoning Plan met the requirements of the code. With the second publication of this opinion, a 30-day period begins during which any "aggrieved" party can file an appeal. Absent such appeal, the Zoning Officer's opinion becomes binding.[54] (See Section 916.2--Preliminary Opinion of the Zoning Officer). On December 21, 2016, seven concerned Whitemarsh Township residents, represented by counsel, filed an appeal, challenging the Zoning Officer's Preliminary Opinion. On January 31, that appeal was heard before the Whitemarsh Township Zoning Hearing Board, but after three hours of testimony and questions, the hearing was continued to March 16, 2017. On February 15, the attorney for the appellants submitted a legal brief, further supporting the challenge to the Preliminary Opinion.

Advocacy

In Spring 2016, the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia placed Abolition Hall/Barn and Hovenden House on its list of "Places to Save," a public registry that "focuses attention and energy towards special places at risk of being lost."[55]

In September 2016, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission issued a letter to Plymouth and Whitemarsh Townships clarifying and reiterating the significance of the Maulsby/Corson/Hovenden homestead. Noting the "inter-related complex of buildings," the letter goes on to state that their 1971 nomination to the National Register of Historic Places "reinforces the important role that these buildings played within the context of the village, as well as their individual historical and architectural significance."[56]

In February 2017, Preservation Pennsylvania (PPA) added the property to its 2017 Pennsylvania At Risk List.[4] The organization also agreed to serve as the fiscal agent for Friends of Abolition Hall, which is raising funds to support the zoning challenge and protect the legacy of the homestead. Online donations are being accepted at Friends of Abolition Hall Fund.

Support the Friends of Abolition Hall -- All new donations are being matched!

The grassroots battle to save the legacy of the Corson homestead continues as the Friends of Abolition Hall challenges the developer's application for conditional use approval. The application is under consideration by the Whitemarsh Township Board of Supervisors, with a Public Hearing having opened on March 22, 2018. Thereafter, hearing was continued on six more occasions, with closing arguments scheduled for September 13, 2018.[57] The Friends group was granted standing in this matter, as was a small number of nearby neighbors. The objections to the proposed townhouse plan are based upon the assertion that it fails to meet the requirements of the Zoning Code, which is a prerequisite to conditional use approval.[58]

Media coverage

Television

- "Battle over Montco's ties to the Underground Railroad," NBC10, Philadelphia, May 7, 2016.[59] The current owner of the Plymouth Meeting Country Store and Post Office took the news crew into the building's cellar and showed them the tunnels that he says were used as part of the Underground Railroad.

Newspapers

- "Plymouth Meeting Quakers hid slaves – It's a shrine of the Underground Railroad," The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 19, 1995.[26]

- "Historical marker for a carriage shed called Abolition Hall," The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 10, 2000.[38]

- "An underground story no more," The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 14, 2012.[27]

- "Coexistence sought for Underground Railroad site and townhouses," The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 9, 2016.[50]

- "Local advocacy group continues years long effort to preserve Abolition Hall," The Times Herald (Norristown, Pennsylvania), April 16, 2018.[58]

- "Don't let developers degrade this historic Underground Railroad stop," The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 2018.[60] Op-Ed column by Sydelle Zove drawing attention to the fate of this precious Underground Railroad site.

- "Abolition Hall advocacy group seeks donations," The Chestnut Hill Local, September 7, 2018.[57]

- "Pennsylvania’s antislavery history is under threat from suburban development ," The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 26, 2018.[61] Column by Inga Saffron, the Pulitzer-Prize-winning design critic for The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Online

- "The Liberation of Jane Johnson," The Library Company of Philadelphia, 2003.[30]

- "The intersection at Butler Pike and Germantown Pike could change as well as the entire landscape," Conshystuff, April 8, 2016.[48]

- "Historic estate and Underground Railroad station under threat in Plymouth Meeting," Hidden City Philadelphia, April 20, 2016.[53]

- "Places to Save," Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia, Fall 2016.[55]

- "2017 Pennsylvania At Risk Announced," Preservation Pennsylvania, February 2017 (PDF).[4]

- "Hope and Despair Surround Philly's African-American Landmarks," Hidden City Philadelphia, February 28, 2020.[62]

Bookplate for the William Jeanes Memorial Library (1939) by Martha M. Hovenden

Bookplate for the William Jeanes Memorial Library (1939) by Martha M. Hovenden

See also

Notes

- The seller was Hester Potts, widow of Nathan Potts, who had purchased the farm from Joshua Lawrence on July 24, 1739.[7]

- Ella K. Barnard wrote that the "old Maultsby house" was located on a 15-acre tract "purchased by Charles Thomas at the time of the settlement of Samuel Maulsby's estate [c.1839], part of which property is now [1909] owned by David Marple." Barnard, page 143.[6]

- Limestone was burned in kilns to produce lime, which would be mixed with water and sand to create mortar.

- Nancy Corson, author of the 1969 NRHP nomination for these buildings, concluded that Samuel Maulsby's c.1795 house incorporated stone walls from an earlier house.[3] This probably would have been the messuage mentioned in the 1794 deed for the corner plot. NOTE: The earlier house could not have been Merchant Maulsby Jr.'s c.1767 stone house, since the corner plot was not part of his farm.[6]

- Robert R. Corson: "While at Uncle George [Corson]'s a slave would knock at the door after dark, be taken in and cared for till next day in the evening, when he would be taken on to Bucks county. At that time our first, great duty was to secure their escape from the slave-hunters, so kept no account of the number of slaves or their history. Sometimes two or three men would come together—at other times women and children, or a man and wife. All were received and well cared for."[21]

- The dockhands were John Ballard, James P. Braddock, William Curtis, James Martin and Isaac Moore.[30]

- Judge John Kintzing Kane: "Of all the parties to the act of violence, he [Williamson] was the only white man, the only citizen, the only individual having recognized political rights, the only person whose social training could certainly interpret either his own duties or the rights of others, under the constitution of the land."[30]

- "The following night, in a close carriage, she [Johnson] was brought to the house of George Corson, at Plymouth Meeting, where for a few days in privacy, she received the kind ministrations of Martha Maulsby Corson, wife of George, and one of the earliest and most devoted of the abolitionists of the region."[33]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "PHMC Historical Markers". Historical Marker Database. Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Nancy Corson (April 1969). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- Press release: "2017 Pennsylvania At Risk Announced" (PDF), Preservation Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, PA, February 2017.

- Haas, Kimberly (28 February 2020). ""Hope and Despair Surround Philly's African-American Landmarks,"". Hidden City Philadelphia. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Ella K. Barnard, Early Maltby, with Some Roades History, and That of the Maulsby Family in America (Baltimore: Ella K. Barnard, 1909).

- Norristown Deeds Book 7, page 492, transcription and map in Barnard, p. 142.

- Maulsby-Albertson Family Papers, from Swarthmore College.

- Pennsylvania Archives Tax Lists – 1769, quoted in Barnard, p. 145.

- Cora M. Payne, Genealogy of the Maulsby Family for Five Generations (Des Moines, IA: George A. Miller Press, 1902).

- "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Edward T. Addison (1980–1983). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Cold Point Historic District" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia, Volume 2 (Philadelphia: 1830), pp. 61-62.

- Hiram Corson, M.D. "George Corson," The Corson Family: A History of the Descendants of Benjamin Corson, Son of Cornelius Corssen of Staten Island, New York. (Philadelphia: H.L. Everett, 1906), pp. 112-17.

- Norristown Deed Book #9, page 180, transcription in Barnard, p. 146.

- Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall, from Philadelphia Architects and Buildings.

- Ellwood Roberts, Plymouth Meeting: Its Establishment, and The Settlement Of The Township, (Norristown, PA: Roberts Publishing Company, 1900).

- Maulsby-Albertson Family Papers, 1763-1884, RG 5/099, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College.

- Norristown Deeds Book 66, page 341.

- Cold Point Historic District, from LivingPlaces.com.

- Hiram Corson, M.D. "The Plymouth Group," The Abolitionists of Montgomery County, (Norristown, PA: Historical Society of Montgomery County, 1900), pp. 41-43.

- Hiram Corson, M.D., "The Norristown Group," The Abolitionists of Montgomery County, (Norristown, PA: Historical Society of Montgomery County, 1900), pp. 29-36.

- Charles Waddell Chesnutt, Frederick Douglass, (Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1899), p. 18.

- "History at the Crossroads, The Activists and Artists of Abolition Hall". PFW Media. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- Thomas Hovenden: American Painter of Hearth and Homeland, Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia, 1995. ISBN 1-888008-00-8.

- William Still, The Underground Rail Road (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872), p. 723.

- Ron Avery, "Plymouth Meeting Quakers Hid Slaves – It's A Shrine Of The Underground Railroad," The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 19, 1995.

- Annette John-Hall, "An underground story no more," The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 14, 2012.

- Hiram Corson, M.D. "Upper Dublin and Horsham," The Abolitionists of Montgomery County, (Norristown, PA: Historical Society of Montgomery County, 1900), p. 44.

- William J. Switala, Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania, (Stackpole Books, 2001), pp. 160-61.

- Phil Lapsansky, "The Liberation of Jane Johnson," The Library Company of Philadelphia, 2003.

- Jane Johnson, from American National Biography.

- William Still, The Underground Rail Road (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872).

- Hiram Corson, M.D. "The case of Jane Johnson and her boys of seven and eleven years," The Abolitionists of Montgomery County, (Norristown, PA: Historical Society of Montgomery County, 1900), p. 26.

- Narrative of the Facts of the Case of Passmore Williamson (1855), from Library Company of Philadelphia.

- Friends' Intelligencer and Journal. Friends' Intelligencer Association. 1898-01-01.

- Theodore Weber Bean, "The Corson Family," History of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Volume 2, (Unigraphic, 1884), pp. 1036-37.

- Anne Gregory Terhune et al., Thomas Hovenden, His Life and Art, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), p. 101.

- Melia Bowie, "Historical marker for a carriage shed called Abolition Hall," The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 10, 2000.

- Helen Reichart Mirras (December 1969). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Plymouth Friends Meetinghouse" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- William Still, The Underground Rail Road (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872), p. 721.

- "Helen Corson Hovenden," from Art Price.

- "Thomas Hovenden, 1840 – 1895," from National Academy of Design.

- Lee M. Edwards, "Noble Domesticity: The Paintings of Thomas Hovenden," American Art Journal:19 (1987): 5-38.

- Helen Corson Hovenden, "Thomas Hovenden," Historical Sketches: A collection of papers prepared for the Historical Society of Montgomery County, Volume 4, (Norristown, PA: Historical Society of Montgomery County, ), p. 5.

- Ernest Pfattiecher, "Thomas Hovenden," The Book News Monthly, vol. 5, no. 25 (January 1907), p. 305.

- Martha Hovenden and Her Dog (1888), from Woodmere Art Museum.

- American Numismatic Society, "Martha M. Hovenden," Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Contemporary Medals (De Vinne Press, 1911), p. 140.

- Brian Coll, "The intersection at Butler Pike and Germantown Pike could change as well as the entire landscape," Conshystuff, April 8, 2016.

- "Abolition Hall (Thomas Hovenden) Historical Marker," from Explore PA History. NOTE: The article gets some of the dates wrong, and mistakes the barn for the carriage house.

- Kristin E. Holmes, "Coexistence sought for Underground Railroad site and townhouses," The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 9, 2016.

- Subdivision sketch plan for Whitemarsh Corson Estate, from Hidden City Philadelphia.

- Sydelle Zove, "Underground Railroad site threatened," The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 2016.

- Michael Bixler, "Historic estate and Underground Railroad station under threat in Plymouth Meeting," Hidden City Philadelphia, April 20, 2016.

- http://dced.pa.gov/download/pennsylvania-municipalities-planning-code-act-247-of-1968/#.WBQJvy0rKpo

- "Places to Save," Extant Magazine (Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia, Fall 2016), pp. 14-15.

- September 8, 2016 letter from the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office re Plymouth Meeting National Historic Register District.

- "Abolition Hall advocacy group seeks donations," The Chestnut Hill Local, September 2018.

- Dutch Godshalk, "Local advocacy group continues years long effort to preserve Abolition Hall," The Times Herald (Norristown, Pennsylvania), April 16, 2018.

- Deanna Durante, "Battle over Montco's ties to the Underground Railroad," NBC10 (Philadelphia), May 7, 2016.

- Sydelle Zove, "Don't let developers degrade this historic Underground Railroad stop," The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 2018.

- "Pennsylvania’s antislavery history is under threat from suburban development ," The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 26, 2018.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hovenden House, Barn and Abolition Hall. |