History of Cumbria

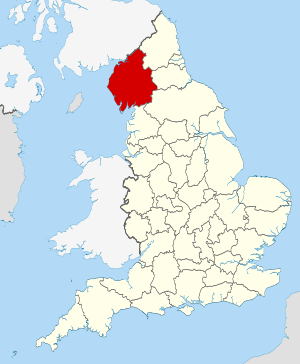

The history of Cumbria as a county of England begins with the Local Government Act 1972. Its territory and constituent parts however have a long history under various other administrative and historic units of governance. Cumbria is an upland, coastal and rural area, with a history of invasions, migration and settlement, as well as battles and skirmishes between the English and the Scots.

Overview

Cumbria was created as a county in 1974 from territory of the historic counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Lancashire North of the Sands and a small part of Yorkshire, but the human history of the area is ancient. It is a county of contrasts, with its mountainous central region and lakes, fertile coastal plains in the north and gently undulating hills in the south.

Cumbria now relies on farming as well as tourism as economic bases, but industry has historically also played a vital role in the area's fortunes. For much of its history Cumbria was disputed between England and nearby Scotland. Raids from Scotland were frequent until the Acts of Union 1707 and its long coastline was earlier vulnerable to Irish and Norse raids.

Cumbria has historically been fairly isolated. Until the coming of the railway, much of the region was hard to reach, and even today there are roads which make many motorists a little nervous. In bad winters, some of the central valleys are occasionally cut off from the outside world. Enclaves of Brythonic Celts remained until around the 10th century, long after much of England was essentially 'English'; and the Norse retained a distinct identity well into the Middle Ages. After that Cumbria remained something of a 'no mans' land' between Scotland and England, which meant that the traditional Cumbrian identity was neither English nor Scottish.

This article is about the area that became the county of Cumbria in 1974, and its inhabitants. Although the term Cumbria was in use in the 10th century AD, this was a description of an entity belonging to the small kingdom of Strathclyde. In the 12th century, Cumberland and Westmorland came into existence as administrative counties.

Prehistoric Cumbria

'Prehistoric Cumbria' describes that part of north-west England, subsequently the county of Cumbria, prior to the coming of the Romans. Barrowclough puts the archaeological record of the county (as of 2010) at '443 stone tools, 187 metal objects and 134 pots', plus the various monuments such as henges, stone circles, and the like. The survival of these objects has been influenced by processes such as the rise in sea levels on the west coast, erosion, deposition practices, industrial and agricultural development, and the changing interests and capabilities of antiquarians and archaeologists.[1]

The first permanent inhabitants of the Cumbria region were based in caves during the Mesolithic era. The Neolithic saw the construction of monuments and the running of the axe 'factory' from which stone axes were carried around the country. The Bronze Age saw continuity with the Neolithic way of living and Iron Age Cumbria saw the establishment of the Celtic tribes – possibly those called the Carvetii and Setantii by the Romans.

Late Upper Palaeolithic, c. 12670–9600 BCE: the earliest human inhabitants

The first evidence found for human occupation in Cumbria is that at Kirkhead Cave, in Lower Allithwaite, during the Federmesser culture period (c. 11400–10800 BCE).[2][3] Discussing the Kirkhead Cave finds, Barrowclough quotes an earlier source who says: "Although limited, the Late Upper Paleolithic material from Cumbria is the earliest evidence of settlement in Britain this far north-west and as such is of national importance."[4][5] (Perhaps this should now read "settlement in England", rather than Britain, as a cave site in Scotland has since been found).[6] Talking of the archaeological finds, he also says: "Lithic material from Kirkhead Cave near Grange ... has been dated to ... c. 11000–9500 BCE"[7] (See: Lithic flake). Other lithic blades were found at Lindale Low Cave at the mouth of the River Kent, in caves at Blenkett Wood, Allithwaite, and at Bart's Shelter, Furness (including reindeer and elk bones).[7]

During the following Younger Dryas stadial (colder period), c. 10890–9650 BCE, Federmesser sites were abandoned, and Cumbria (along with the rest of Britain) was not permanently occupied until the end of the Younger Dryas period, 11,600 years ago (that is, during the Mesolithic era).

Mesolithic, c. 9600–4000 BCE

The Mesolithic era in Cumbria saw a warming of the climate.

It is thought that settlers made their way across Morecambe Bay and along the fertile coast. At that time the upland central region of the county was heavily forested, so humans probably kept to the coastal areas, and around estuaries in particular: "sheltered locations around estuaries, lagoons or marine inlets"[8] "The reason is probably due to the variety and abundance of food resources combined with fresh water and shelter that make estuaries more favoured locations than purely coastal sites".[9]

Evidence for the Early Mesolithic period in Cumbria is largely confined to finds in caves. In the 1990s, human bones were found in Kents Bank Cavern (in the north Morecambe Bay area) which were in 2013 dated to the early Mesolithic, making the find "the most northerly early Mesolithic human remains in the British Isles". Horse and elk remains, from an earlier date, were also found.[10] For the Late Mesolithic, evidence comes from pits at Monk Moors and burning of heathland in the Eden Valley floodplain.[11]

In the north Cumbrian plain, around the Carlisle area and into southern Scotland, evidence has been found for woodland clearance and deliberate fire-setting as a method of managing the landscape during the Mesolithic period.[12]

Large Mesolithic flint-chipping sites, where flints washed up from the Irish Sea were worked into tools, have been found at Eskmeals, near Ravenglass on the west coast, and at Walney in the south. At Williamson's Moss in the Eskmeals area, Bonsall discovered 34,000 pieces of worked flint (pebble flint), chert and tuff, plus wooden raft-like structures that suggest permanent or semi-permanent settlement by the wandering hunter-gatherer population. Over 30,000 artefacts were discovered at Monk Moors, also part of the Eskmeals raised shoreline area.[13] These sites were probably used across several thousands of years, not just during the Mesolithic.[14]

Neolithic, c. 4500–2350 BCE

There is much more visible evidence of Neolithic activity than of any earlier period. This consists mostly of finds of axes and the presence of monuments (stone circles, cairns). However, "there are few settlement traces represented either by physical structures or surface flintwork ... pottery finds are ... very poorly represented in Cumbria".[15] This was a time of technological advances and population expansion. The change from Mesolithic to Neolithic in Cumbria was gradual and continual. The change "is marked by the appearance of ... leaf-shaped arrowheads, scrapers and polished stone axes together with pottery and ceremonial and funerary monuments".[16]

At some time, the Mesolithic coastal communities must have moved further inland, probably following rivers along valley corridors into the heart of Lakeland. But we do not know how many moved. "The small amount of early Neolithic flintwork from the coastal plain has been taken to suggest a move away from the coast inland where the monuments of the Neolithic tend to be located. An alternative view suggests that the same level of coastal settlement and exploitation that had been common in the Mesolithic continued into the Neolithic, but that in the later period there was also an expansion of activity into other parts of the landscape"[17]

The best-known Neolithic site in the West Cumbrian Plain is Ehenside Tarn near Beckermet, with roughout (unfinished) and polished axes, plain bowl pottery, cattle and deer bones. The evidence of deer bones here and at Bardsea in South Cumbria suggests a continuation of hunter-gathering alongside more settled, agricultural, means of living. Ehenside points up the use of wetland areas by Neolithic Cumbrians: The finds there were discovered when the Tarn was drained. "Wetland areas, whether open water or bog, were foci for beliefs and ritual practices alongside contemporary monuments, and it is, therefore, interesting to note there was a standing stone near Ehenside Tarn".[18]

South Cumbria, and especially Furness and Walney, is the area where most of the axe finds have been made (67 examples – accounting for half of the total of axe finds in Cumbria). This is probably due to the area's proximity to the so-called 'Langdale Axe Factory'. Many of the axes seem to have been intentionally deposited in moss areas and in fissures in rocks.[19]

Indeed, that axe factory is perhaps the most famous and important find of Neolithic activity in Cumbria: Many thousands of axe heads were made there from the green volcanic tuff found on the Pike O'Stickle from around 6000 BCE. The axe heads were not only for local use in weapons: They have been found widely over the United Kingdom from Norfolk to Northern Ireland, and seem to have often been used for ceremonial or ritual purposes.

Also at this time, possibly reflecting economic power created by the Axe Factory, stone circles and henges began to be built across the county. Indeed, "Cumbria has one of the largest number of preserved field monuments in England".[20] The Neolithic examples include the impressive henge at Mayburgh, near Penrith, and a partly destroyed one at nearby King Arthur's Round Table (KART); as well as the Castlerigg Stone Circle above Keswick. The megalith Long Meg, along with Little Meg and a circle at Glassonby may also have been erected at this time, although they are also possibly early Bronze Age in date.

Some of the stones have designs (spirals, circles, grooves and cup-marks) on them which may have indicated the presence of other monuments or gathering-places and/or signalled the trackways and other routes through the landscape, particularly through the river valleys to sources of food, to ritual gathering places, or to sources of axes.[21][22]

As well as providing focal points for the gathering of people for the purposes of trade, of ritual, and, in the Late Neolithic, for more 'tenurial' settlement and ownership of land, the stone circles probably had cosmological uses as well. For example, the Long Meg stone itself, which stands outside its accompanying circle, is aligned with the circle's centre on the point of the midwinter sunset. The use of different coloured stones here is possibly linked to observations made at the times of equinoxes and solstices.[23]

Bronze Age, c. 2500–700 BCE

By the Bronze Age, settlements in Cumbria are likely to have taken a much more permanent form. Like the transition from Mesolithic to Neolithic, the transition from Neolithic to Early Bronze Age was gradual and continuity of sites is likely. Unlike in southern England, where the transition is marked by the 'Beaker Period', in Cumbria and the north-west burials with beaker pottery are rare, with only a handful of such burials recorded. (Instead, circular wooden and then stone structures subsequently sealed by cairns and used over centuries was the preferred method.)[24]

In the Early Bronze Age, evidence of greatly increased woodland clearing combined with cereal growing has been found in the pollen record for the North Cumbrian Plain, Solway Firth and the coastal areas. Very little evidence of occupation exists, although a number of potential sites have been identified by aerial photographic work.[25] The site at Plasketlands seems typical of "a combination of arable, grazing, peat, alluvium and marine resources".[26]

Collared urns have been found at sites such as the former Garlands Hospital (now the Carleton Clinic near Carlisle), Aughertree Fell, Aglionby, and at Eskmeals (with a cist burial, cremation pits, and a flint-knapping site). Activity round the Morecambe Bay region seems to have been less than in the West Cumbrian Coastal Plain, although there is evidence for significant settlement on Walney Island, and at Sizergh, Levens Park and Allithwaite where Beaker burials took place.

This southern area of the county also has approximately 85 examples of perforated axe-hammers, rarely found in the rest of the county. These, like the Neolithic stone axes, seem to have been deposited deliberately (with axe finds being more coastal in distribution).[27] The increase in the use of these perforated axes probably accounted for the decline in the Langdale axe factory which occurred c. 1500 BCE. "New designs of perforated stone axes were developed, and Langdale tuffs were discovered by experiment to be too fragile to allow perforation."[28] Non-perforated axes were abandoned and other sources of lithic material were sought from other parts of the England. Copper and bronze tools only seem to have arrived in Cumbria very gradually through the 2nd millennium. Indeed, by c. 1200 BCB there is evidence of a breakdown in technology usage and trade between the northern, highland areas, including Cumbria, and the southern areas of the country.[29] This was not compensated for by home-grown metallurgical working.

In terms of burial practices, both inhumations (burials of non-cremated bodies) and cremations took place in Cumbria, with cremations (268) being more favoured than inhumations (51). Most burials were associated with cairns (26) but other monuments were also used: round barrows (14); 'flat' cemeteries (12); stone circles (9); plus use of ring cairns, standing stones and other monuments.[30] Burials for inhumations (in barrows and cairns) are found on the surface, as at Oddendale, or in pits, usually with a cist formed in it, as at Moor Divock, Askham. Cremation burials may also be found "in a pit, cist, below a pavement, or roughly enclosed by a stone cist".[31] Often, there are multiple burials not associated with any monument – another indication of continuity with Neolithic practice. Cremated bones placed in food vessels was followed by a later practice of placement in collared or uncollared urns, although many burials had no urns involved at all. A capping stone was often placed on the urn, which could be either upright or inverted. Ritualistic deposition into Cumbrian grave-sites include: broken artefacts, such as single beads from a necklace (as at Ewanrigg); sherds of Beaker or Collared Urn pottery; bone pins, buttons, jet, slate, clay ornaments; ochre, or red porphyry and quartz crystals (as at Birkrigg, Urswick); knives, daggers and hunting equipment.

Bronze Age artefacts have been uncovered throughout the county, including several bronze axe heads around Kendal and Levens, an axe and a sword at Gleaston, a rapier near the hamlet of Salta, an intriguing carved granite ball near Carlisle and part of a gold necklace believed to be from France or Ireland found at Greysouthen. A timber palisade has also been discovered at High Crosby near Carlisle. Again, there is continuity between Bronze-age and Neolithic practice of deposition. There seems to be an association between the distribution of stone perforated axe-hammers and bronze metalwork deposition in the area of Furness.[32] Of the approximately 200 bronze implements found in Cumbria, about half have been found in the Furness and Cartmel region. Most are flanged axes (21), and flanged spearheads (21), palstaves (20), and flat and socketed axes (16 each).[33] Early Bronze Age metalwork distribution is largely along communication valleys (such as the Eden valley), and on the Furness and West Cumbrian plains, with evidence on the west coast (for example, a find at Maryport) of connections with Ireland.[34] In the Middle Bronze Age, deposition seems to have switched from burials to wet places, presumably for ritualistic reasons. In the Late Bronze Age, socketed axe finds are the most common (62), but are rare in West Cumbria, which also lacks finds of the angle-flanged type.[35] Hoards (two or more items) of deposited Bronze Age metalwork are rare in Cumbria, (notably at Ambleside, Hayton, Fell Lane, Kirkhead Cave, Skelmore Heads), for reasons that are still being discussed. Most are from the Middle Bronze Age period.

As mentioned above, evidence of actual metalworking in Cumbria during this period is scarce. There is some sign of copper ore extraction around the Coniston area, but the most notable find is of a tuyère, (a clay pipe connecting the bellows to a furnace), found at Ewanrigg[36] and which is a rare example from the Early Bronze Age. Two-part stone moulds have also been found at Croglin.

Ritual or 'religious' sites can be seen across the county and are often clearly visible. Cairns and round barrows can be found throughout the area and a cemetery has been discovered near Allithwaite. More impressive remains include stone circles, such as Birkrigg stone circle, Long Meg and Her Daughters, Swinside, and Little Meg. 32 bronze artefacts have been discovered in the Furness district covering a long period of time (c. 2300–500 BCE), suggesting that this region was held to have special meaning to the people there. In the Late Bronze Age, defended hilltop settlements along the northern shore of Morecambe Bay, with metalworking, special functions and long-term deposition of artefacts associated with them, were probably precursors to later Iron Age hill-forts. However, many of these defended settlements appear to have been abandoned, probably due to a deterioration in the climate from c. 1250 BCE to roughly the beginning of the Iron Age.

Iron Age, c. 800 BCE–100 CE

The Iron Age in Britain saw the arrival of Celtic culture – including certain art forms and languages – as well as the obvious increase in the production of iron. The people of Great Britain and Ireland were divided into various tribes: In Cumbria the Carvetii may have dominated most of the county for a time, perhaps being based in the Solway Plain and centred on Carlisle,[37] although an alternative view has their pre-Roman centre at Clifton Dykes.[38] The Setantii were possibly situated in the south of the county, until both were perhaps incorporated into the Brigantes who occupied much of northern England. (The status – especially that of the relationship with the Brigantes – and location of the Carvetii and Setantii is disputed by historians). They probably spoke Cumbric, a variety of the ancient British language of Brythonic, (or Common Brittonic), the predecessor of modern Welsh, and probably named some of the county's topographical features such as its rivers (e.g. Kent, Eden, Cocker, Levens) and mountains (e.g. Blencathra).

There appear to be many remains of Iron Age settlement in Cumbria, including hill forts such as those at Maiden Castle [39] and Dunmallard Hill[40] and many hundreds of smaller settlements and field systems. However, securely dateable evidence of Iron Age activity in Cumbria is thin.[41] In North Cumbria, hillforts have been dated to c. 500 BCE at Carrock Fell and Swarthy Hill, as well as a burial at Rise Hill and a bog body at Scaleby Moss.

A large number of enclosure sites have been identified from aerial photographs in the Solway Plain. There are also possible sites re-used by the Romans at Bousted Hill and Fingland, as well as at Ewanrigg[42] and Edderside.[43] Early Iron Age finds in West Cumbria are limited to sites at Eskmeals and Seascale Moss (with another bog body). In the south, 'hillforts' have been identified at Skelmore Heads, Castle Head, Warton Crag and an enclosure at Urswick. However, Cumbria appears not to have any of the so-called 'developed hillforts' (enlarged from earlier versions, around 3–7 ha in area, with multiple ditches and complex entrances),[44] suggesting that few, if any, were still being used in the pre-Roman Iron Age, apparently having been abandoned.[45]

The abandonment of land and settlements noted above is probably explained by climate change. Between c. 1250 BCE and c. 800 BCE, the climate deteriorated to the extent that, in Cumbria, upland areas and marginal areas of cultivation were no longer sustainable. Woodland clearing happened, however, combined with signs of increased soil erosion: production capacity may have been seriously affected, with agriculture being forcibly replaced by pastoralism, and with a resultant "population crisis" at the beginning of the Iron Age.[46]

However, an improvement in climatic conditions from c. 800 BCE to c. 100 CE occurred. A major de-forestation period, linked to increased cereal production, seems to have taken place (according to pollen records) towards the end of the 1st millennium BC. This is also associated with a slight rise in sea level that may explain the lack of evidence for low-lying settlements. There is sparse evidence for the Late Iron Age and early Romano-British periods. Nevertheless, enclosures seen from aerial photography in upland areas such as Crosby Garrett and Crosby Ravensworth, together with similar evidence from the Solway Plain and Eden Valley, (see the section below on Life in Roman Cumbria for a listing of the main sites), point to the populous nature of the territory held by the Brigantes (as noted by Tacitus in the 'Agricola').[47] The view of historians now seems to be that the hillforts were becoming centres of economic activity and were less in the nature of dominating power-centres. "Indeed, the north-west, far from being a backward region of Britain in the late Iron Age, can be seen as progressive and entrepreneurial."[48] This was true, however, only in certain areas of the north-west: the Solway Plain, the Eden and Lune valleys, and perhaps southern Cumbria and Cheshire, which may have been "thriving".[49]

The traditional Iron Age roundhouse, enclosed by a ditch and revetted bank, was used by the Carvetii. Sometimes, dry-stone walls were used instead of the bank. However, a roundhouse at Wolsty Hall has two opposed entrances and a ring-grooved external wall, which may indicate a northern, regional variety of roundhouse building.

(Later, in the mid-Roman period, probably in the 3rd century, a change took place in that the round structures were replaced by rectilinear buildings on some sites).

Most of the population, the total size of which at its peak has been estimated at between 20,000–30,000 people,[50] lived in scattered communities, usually consisting of just a single family group. They practised mixed agriculture, with enclosures for arable use, but also with enclosed and unenclosed pasture fields.[51]

Evidence of burial practices is extremely rare. Inhumations have been found at Risehow, and possibly at Butts Beck (crouched individuals in pits and ditches) as well as two very rare cemeteries with multiple individuals (only approximately 30 Iron Age cemeteries exist in Britain in total) at Nelson Square, Levens and at Crosby Garrett.[52] The Butts Beck burial included the body of a 'warrior' along with his weapons and a horse (although this might have been a horse and cart burial, rather than a warrior one, with the wooden cart having rotted away).[53] The bog body at Scaleby[54] and the one at Seascale[55] are difficult to date, and, since the excavations were done in the 19th century and lacked today's archaeological techniques, the evidence for Druidical ritual sacrifice, as appears with some other bog bodies in Britain and Europe, is not present in the Cumbrian examples. However, both bodies were buried with a wooden stick or wand, which conforms to other bog-burial practice elsewhere. The finding of stone heads at Anthorn and at Rickerby Park, Carlisle, also conforms to the Celtic cult of the severed head and ritualistic sacrifice. This may be true also of the bronze buckets or cauldrons deposited at Bewcastle and at Ravenstonedale[56] which indicate connections with Ireland. The early name of Carlisle, 'Luguvalium', meaning 'belonging to Luguvalos', suggests a tribal chief in charge who had a personal name that meant 'strong as Lugus'. This indicates a possible affinity of the tribe there (perhaps the Carvetii) to the Celtic god Lugus, whose festival, Lugnasad, occurred on 1 August, accompanied by various sacrifices.

Hoards of deposited Cumbrian Iron Age metalwork show evidence of a regional variation, with Cumbrian hoards being mostly of weapons buried off-site and consisting of small numbers of items. This fits the picture of Iron Age Cumbria, as with the rest of the north-west, consisting mostly of small, scattered, farmsteads.[57][58] In the 18th century a beautiful iron sword with a bronze scabbard, dating from around 50 BCE, was found at Embleton near Cockermouth; it is now in the British Museum.

Roman Cumbria

Roman Cumbria was an area that lay on the north-west frontier of Roman Britain, and, indeed, of the Roman Empire itself. (The term 'Cumbria' is a much later designation – the Romans would not have used it). Interest in the Roman occupation of the region lies in this frontier aspect – why did the Romans choose to occupy the north-west of England; why build a solid barrier in the north of the region (Hadrian's Wall); why was the region so heavily militarised; to what extent were the native inhabitants 'Romanised' compared to their compatriots in southern England?

The decision to conquer the area was taken by the Romans after the revolt of Venutius threatened to make the Brigantes and their allies, such as the Carvetii, into anti-Roman tribes, rather than pro-Roman ones which had previously been the case. After a period of conquest and consolidation, based on the Stanegate line, with some coastal defences added, Hadrian decided to make the previous turf wall into a solid one. Although abandoned briefly in favour of the more northerly Antonine Wall, the Hadrianic line was fallen back upon and remained for the rest of the Roman period.

Such unrest as occurred during the Roman occupation seems to have been the result of either incursions by tribes to the north of the Wall, or as the result of factional disputes in Rome in which the Cumbrian military was caught up. There is no evidence of the Brigantian federation stirring up trouble. Romanisation of the population may therefore have occurred to varying degrees, especially near the forts.

Conquest and consolidation, 71–117 AD

After the Romans' initial conquest of Britain in 43 AD, the territory of the Brigantes remained independent of Roman rule for some time. At that time the leader of the Brigantes was the queen Cartimandua,[59] whose husband Venutius might have been a Carvetian and may therefore be responsible for the incorporation of Cumbria into the Brigantian federation. It may be that Cartimandua ruled the Brigantian peoples east of the Pennines (possibly with a centre at Stanwick), while Venutius was the chief of the Brigantes (or Carvetii) west of the Pennines in Cumbria (with a possible centre based at Clifton Dykes.)[60]

Despite retaining nominal independence, Cartimandua and Venutius were loyal to the Romans and in return were offered protection by their Imperial neighbours. But the royal couple divorced, and Venutius led two rebellions against his ex-wife. The first, in the 50s AD, was quashed by the Romans, but the second, in AD 69, came at a time of political instability in the Empire and resulted in the Romans evacuating Cartimandua and leaving Venutius to reign over the Brigantes.

The Romans could not accept a formerly pro-Roman tribe the size of the Brigantes now being ant-Roman, so the Roman conquest of the Brigantes began two years later. Tacitus gives pride of place in the conquest of the north to Agricola (his father-in-law), who was later governor of Britain during 77–83 AD. However, it is thought that much had been achieved under the previous governorships of Vettius Bolanus (governor 69–71 AD), and of Quintus Petillius Cerialis (governor 71–74 AD).[61] From other sources, it seems that Bolanus had possibly dealt with Venutius and penetrated into Scotland, and evidence from the carbon-dating of the gateway timbers of the Roman fort at Carlisle (Luguvalium) suggest that they were felled in 72 AD, during the governorship of Cerialis.[62] Nevertheless, Agricola played his part in the west as commander of the legion XX Valeria Victrix, while Cerialis led the IX Hispania in the east. In addition, the Legio II Adiutrix sailed from Chester up river estuaries to cause surprise to the enemy.

At some point, part of Cerialis's force moved across the Stainmore Pass from Corbridge westwards to join Agricola. The two forces then moved up from the vicinity of Penrith to Carlisle, establishing the fort there in 72/73AD.[63]

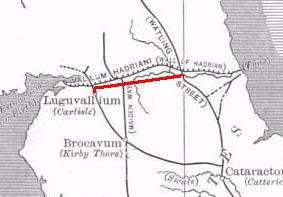

Eventually, a consolidation based on the line of the Stanegate road (between Carlisle and Corbridge) was settled upon. Carlisle was the seat of a 'centurio regionarius' (or 'district commissioner'), indicating its important status.

The years 87 AD – 117 AD were ones of consolidation of the northern frontier area. Only a few sites north of the Stanegate line were maintained, and the signs are that an orderly withdrawal to the Solway-Tyne line was made. There does not seem to have been any rout caused as a result of battles with various tribes.[64]

Apart from the Stanegate line, other forts existed along the Solway Coast at Beckfoot, Maryport, Burrow Walls (near to the present town of Workington) and Moresby (near to Whitehaven). These forts have Hadrianic inscriptions, but some (Beckfoot, for example), may have dated From the late 1st century. The road running from Carlisle to Maryport had turf-and-timber forts along it at Old Carlisle (Red Dial), Caer Mote, and Papcastle (which may have had special responsibility for looking after the largely untouched Lake District region). The forts in the east along the Eden and Lune valley road at Old Penrith, Brougham and Low Borrow Bridge may have been enlarged, but the evidence is scanty. A fort at Troutbeck may have been established from the period of Trajan (emperor 98 AD – 117 AD) onwards, along with an uncertain road running between Old Penrith and/or Brougham, through Troutbeck (and possibly an undiscovered fort in the Keswick area) to Papcastle and Maryport. Other forts that may have been established during this period include one at Ambleside (Galava), positioned to take advantage of ship-borne supply to the forts of the Lake District. From here, a road was constructed during the Trajanic period to Hardknott where a fort was built (the fort at Ravenglass, where the road eventually finished, was built in the following reign of Hadrian (117 AD – 138 AD)). A road between Ambleside to Old Penrith and/or Brougham, going over High Street, may also date from this period. From the fort at Kirkby Thore (Bravoniacum), which stood on the road from York to Brougham (following the present A66), there was also a road, the Maiden Way, that ran north across Alston Edge to the fort at Whitley Castle (Epiacum) and on to the one at Carvoran on the Wall. In the south of the county, forts may have existed from this period south of Ravenglass and in the Barrow and Cartmel region. The only one that survives is at Watercrook (Kendal).[65]

Hadrian, Antoninus and Severus, 117–211 AD

Between 117 and 119, there may have been a war with the Britons, perhaps in the western part of the northern region, involving the tribes in the Dumfries and Galloway area.[66] The response was to provide a frontier zone in the western sector of forts and milecastles, built of turf and timber (the "Turf Wall"), the standard construction method (although some have suggested it was because "turf and timber were preferred on the Solway plain, where stone is scarce").[67]

For whatever reason, this was not enough for the emperor Hadrian (emperor 117 AD – 138 AD). Perhaps the decision to build the Wall was taken because of the seriousness of the military situation, or because it fitted in with the new emperor's wish to consolidate the gains of the empire and to delimit its expansion, as happened on the German frontier, (or possibly both). Hadrian, who was something of an amateur architect, came to Britain in 122 AD to oversee the building of a more solid frontier (along with other measures elsewhere in England). It is possible that Hadrian stayed at Vindolanda (in present-day Northumberland) while planning the wall.[68] Building of Hadrian's Wall along the line of Agricola's earlier garrisons began in 122 AD and was mostly completed in less than ten years, such was the efficiency of the Roman military. It ran from Bowness on the Solway Firth across the north of the county and through Northumberland to Wallsend on the Tyne estuary, with additional military installations running down the Cumbrian coast from Bowness to Risehow, south of Maryport, in an integrated fashion (and with forts at Burrow Walls and Moresby that were perhaps not part of the system).[69][70]

There were several forts and milecastles along the Cumbrian half of the wall, the largest of which was Petriana (Stanwix), housing a cavalry regiment and which was probably the Wall's headquarters (perhaps indicating that the serious unrest was taking place in this western sector of the frontier, or perhaps it was halfway along the distance of the Wall plus the Solway coast installations). Nothing of Petriana has survived, the largest visible remains in Cumbria now belong to the fort at Birdoswald – very little of the Wall itself can be seen in Cumbria. Running to the north of the Wall was a ditch, and to the south an earthwork (the Vallum). Initially, forts were maintained on the Stanegate line, but in around 124 AD – 125 AD the decision was taken to build forts on the Wall itself, and the Stanegate ones were closed down. The Roman forts of Cumbria are "auxiliary forts" – that is, housing auxiliary units of infantry and cavalry, rather than a legion, as at Chester. So-called 'outpost-forts', with road links to the Wall, were built north of the Wall, probably at about the time the Wall itself was built in its turf and timber form. They include Bewcastle and Netherby in Cumbria, and Birrens in Dumfriesshire.

Only twenty years after Hadrian's Wall was started, Antoninus Pius (emperor 138 AD – 161 AD) almost completely abandoned it in 138 AD, a few months after his accession, turning his attentions to his own frontier fortification, the Antonine Wall across central Scotland. Perhaps he wanted to include possible enemies (and friends) within a frontier zone, rather than beyond it, as with Hadrian's scheme. The two walls were not held in conjunction and the coastal fortifications were de-militarised as well. But Antoninus failed to secure control of southern Scotland and the Romans returned to Hadrian's Wall, which was re-furbished, in 164 AD, after which garrisons were retained there until the early 5th century.

The Wall had cut the Carvetti's territory in half and it is possible that there was a certain amount of local raiding and uncertainty derived from them and possibly other local tribes to the north of the Wall. The early 160s saw troubles of some kind on the northern frontier. Continual building of the northern frontier region took place during the turn of the 2nd and 3rd centuries, indicating further troubles. In around 180, the Wall was crossed by hostile forces who defeated one of the Roman armies. However, in the 170s and 180s the real pressure, in terms of disturbances, seems to have come from tribes much further north – the Caledones in particular. Events came to a head when the emperor Septimius Severus, intending to attack the Caledones, established himself at York in 209 AD, designating it the capital of the northern region (although this region, Britannia Inferior, may not have been formally established until after his death in 211). He also strengthened Hadrian's Wall and he may have established the "civitas" (a form of local government) of the Carvetii with its centre at Carlisle (Luguvalium).[71]

Prosperity, troubles, and the 'return to tribalism', 211–410 AD

The settlement of Severus, carried forward diplomatically by his son Caracalla, led to a period of relative peace in the north, which may have lasted for most of the 3rd-century (we are severely hampered by the lack of sources concerning the northern frontier for most of the 3rd century, so this may be a false picture). For the first half of the century, it appears that the forts were kept in good repair and the coastal defences were probably not being used regularly. Power may have been shared between the Civitas and the Roman military. Some forts, such as Hardknott and Watercrook, may have been de-militarised, and parts of the Wall seem to have fallen into disrepair. Evidence of smaller barrack-blocks being built, as at Birdoswald, suggest reduced manning by the army and a sharing between the military and civilian population. Changes in the military across the empire, (such as advancement of soldiers not from the senatorial classes plus greater use of 'barbarian' skilled workers), led to a more lax discipline.[72]

Despite a more settled existence in places like Cumbria, internal strains began to affect the empire as a whole. The internal promotion reform in the army led to various people expecting promotions, which they may not have been given, and this led to tensions and violent outbreaks. Monetary inflation and splits amongst the rulers began to occur in the empire, as various pretenders vied for power in Rome, and these had deleterious effects in Britain. Rebellions in Gaul (259) and by Carausius, a naval commander who usurped power in Britain, and Allectus, who did the same (286), may have affected troops in Cumbria who were forced to take sides: a military clerk was killed at Ambleside, for example. The fight against Allectus may have led to the frontier being denuded of troops in the late 3rd century, with consequent attacks from the north. There is evidence of fire-damage at Ravenglass and other damage elsewhere in the north. The emperor Constantius I came to Britain twice to put down trouble (in 296, defeating Allectus, and in 305 fighting the Picts), and there is evidence of re-building taking place. In the early 4th century, defence-in-depth seems to have become the strategy in the frontier area, with the Wall becoming less of a 'curtain' barrier and more reliance being placed on the forts as 'strongpoints'.[73]

The reforms of the emperors Diocletian and Constantine led to prosperity, in the south of the country at least, but this stability did not long outlast the death of Constantine in 337. The 330s and 340s saw a return to civil wars in the empire and, again, Britain was affected. It may be that the visit of the emperor Constans to Britain in 342–343 was to do with disaffection amongst British troops or "apparently to deal with problems on the northern frontier.".[74] It is possible that the west coast of England and Wales was strengthened in a way similar to that of the southern ('Saxon Shore') defensive system. How this affected the Cumbrian coast is uncertain, but it appears that the forts at Ravenglass, Moresby, Maryport and Beckfoot were maintained and occupied, and there is evidence that some of the Hadrianic coastal fortlets and towers were re-occupied, such as at Cardurnock (milefortlet 5).[75]

The usurpation of Magnentius and his defeat in 353 may have further increased troubles in Britannia. Attacks on the province took place in 360 and, some years later, secret agents, known as the Areani (or 'Arcani'), operating between Hadrian's Wall and the Vallum as intelligence-gatherers, were involved in the Great Conspiracy of 367–368. They were accused of going over to the enemies of the empire, such as the Picts, the Scotti (from Ireland), and the Saxons, in return for bribes and the promise of plunder.[76]

Some of the 'outpost-forts' north of the Wall, and others such as Watercrook, seem not to have been maintained after 367, but Count Theodosius, or maybe local 'chieftains', did a fair amount of re-building and recovery work elsewhere. There is evidence of a narrowing of the gateway at Birdoswald, and structural changes at Bowness-on-Solway and Ravenglass, for example. There may also have been new fortlets at Wreay Hall and Barrock Fell, and possibly at Cummersdale, all south of Carlisle.[77]

After the 360s there appears to have been a 'marked decline in the occupation of vici',[78] possibly due to the clearing out of the 'areani' by Theodosius.[79] Also, army supplies were increasingly shipped in from imperial factories on the continent. The continuous loss of numbers of troops (drawn away to fight elsewhere), plus the ravages of inflation, meant that there was little reason left for local inhabitants of the vici to remain. The raids by the Picts and Scots in the late 4th and early 5th centuries (the so-called 'Pictish Wars'), meant increasing strain. For example, between 385 and 398 (when Stilicho cleared the raiders out), Cumbria was 'left to its own devices'.[80]

The various phases of re-modelling of the Birdoswald fort in the second half of the 4th century suggest that it was becoming more like a local warlord's fortress than a typical Roman fort. It may be that local people were looking more to their own defence (perhaps influenced by Pelagian thought about self-salvation), as Roman authority waned (for example, taxation-gathering and payment to the troops gradually ceased). In the northern frontier area at least, it looks as though the local Roman fort commander became the local warlord, and the local troops became the local militia operating a local 'protection racket',[81] without any direction from above. This was what Higham called a "return to tribalism", dating perhaps from as early as 350 onwards.[82] The Roman 'abandonment' of Cumbria (and Britain as a whole) was therefore not a sudden affair, as the famous advice of Honorius in 410, supposedly to the Britons ( that is, to look to their own defence) suggests. The Romano-British, in the north at least, had been doing that for some time.

Life in Roman Cumbria

The severe lack of available evidence makes it difficult to draw a picture of what life was like in Roman Cumbria, and to what extent "Romanisation" took place (although the Vindolanda tablets give us a glimpse of Roman life on the, mostly, pre-Hadrian's Wall frontier). The auxiliary troops stationed in the forts obviously had an impact. Land around forts was appropriated for various uses – parade grounds, annexes (as at Carlisle), land given to retired troops for farming use, mining operations (copper in the Lake District, lead and silver around Alston), and so on. Around most forts, a vicus (plural, vici) – a civilian settlement – may have been established, consisting of merchants, traders, artisans, and camp-followers, drawn to the business opportunities provided by supplying the troops. The beginnings of something like town life can be seen, but probably not with the same extent of urbanisation and wealth as in the south of England.[83]

.jpg)

Apart from settlements associated with the forts, Roman Cumbria consisted of scattered rural settlements, situated where good agricultural ground was to be found in the Solway Plain, the West Coastal Plain, and in the valleys of the Eden, Petteril, and Lune.

Most of the population, the total size of which at its peak has been estimated at between 20,000–30,000 people,[84] lived in scattered, but not isolated, communities, usually consisting of just a single family group. They practised mixed agriculture, with enclosures for arable use, but also with enclosed and unenclosed pasture fields.[85] During the second half of the Roman occupation, there seems to have been a move from agricultural land to pasture and 'waste' with building of walls and barriers – perhaps due either to a fall-off in demand for grain locally, consequent on the decline of the Roman military establishment, or to a drop in productivity.[86]

It is difficult to assess the long-term effects of the Roman occupation on the native inhabitants of Cumbria. The evidence gleaned from artefacts such as the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan (also known as the Ilam Pan), suggests that a Romano-British adaptation of Celtic art persisted in Cumbria. One expert says that: "... Celtic tradition survived in Roman disguise ...", and that "the Romanisation of Britain was in many ways nothing but a surface veneer."[87] (The pan was probably a souvenir of Hadrian's Wall, inscribed with the names of some of the Cumbrian forts in the 2nd century, along with the name of the owner, perhaps an ex-soldier, showing that the Wall was noteworthy enough in Roman times to be remembered.)

In a superstitious age, religion was a factor that may have helped to bridge the divide between Roman and Celtic ways of life to form a Romano-British culture. After the destruction of the Druids, there is evidence of a mixing of Roman mystery-cults with local Celtic deities, alongside formal Roman cults of the emperor and worship of the Olympian gods.

All in all, the old model of Roman 'conquerors' and local 'vanquished' in Cumbria and the north, is superseded by one that sees that, "within limits, the local population became Romanised".[88]

Medieval Cumbria

Early medieval Cumbria, 410–1066

After the Romans: warring tribes and the Kingdom of Rheged, c. 410–600

As outlined above, by the official Roman break with Britannia in 410, most of Britain was already effectively independent of the empire. In Cumbria, the Roman presence had been almost entirely military rather than civil, and the withdrawal is unlikely to have caused much change. The power vacuum was probably filled by local warlords and their retainers who fought it out for control over various regions, one of which may have been Rheged. However, questions remain as to what post-Roman Cumbria looked like, in terms of its political and social life.

Sources – history and legend

The questions mentioned above remain to be answered because now we enter the period that used to be called the Dark Ages, due to the lack of archaeological and paleobotanical finds, (although the last few decades have provided more in the way of archaeological evidence due to the improvement in dating, especially by means of radiocarbon analysis),[89] and the unreliability of the documentary sources that we are forced to use as a result. Some historians, therefore, dismiss some well-known figures of the 5th and 6th centuries, potentially connected with Cumbria, as being legendary or -pseudo-historical. King Arthur, Cunedda and Coel Hen are some of these figures.

As far as Arthur is concerned, as with many other areas with Celtic connections, there are a number of Arthurian legends associated with Cumbria.

After the Roman withdrawal, Coel Hen may have become the High King of Northern Britain (in the same vein as the Irish Ard Rí) and ruled, supposedly, from Eboracum (now York).

Warring tribes

The successive withdrawals of Roman troops from Cumbria throughout the 4th and early 5th centuries created a power vacuum which, by necessity, was filled by local warlords and their followers, often just based around a single village or valley. The main strife of this period was created by the local 'tyrants', or warlords, fighting amongst themselves, raiding and defending themselves against raids.

Local 'kings', with successors, were continually being made and unmade in this intertribal warfare, and by the end of the 6th century some had gained a lot of power and had formed kingships over a larger area. One of these was Coroticus of Alt Clut (Strathclyde), and Pabo Post Prydain was another (he may have been based at Papcastle). Rheged seems to have been one of these members of the Old North kingdoms that emerged during this period of intertribal warfare.[90]

Rheged

The extent of Rheged is disputed: none of the early sources tells us where Rheged was located.[91] Some historians believe that it was based on the old Carvetii tribal region – mostly covering the Solway plain and the Eden valley. Others say that it may have included large parts of Dumfriesshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire. The Kingdom's centre was based, possibly, at Llwyfenydd, believed to be in the valley of the Lyvennet Beck, a tributary of the River Eden in east Cumbria, or, alternatively, at Carlisle.

The little that is known about Rheged and its kings comes from the poems of Taliesin, who was bard to Urien, King of Catraeth and of Rheged (and possibly overlord of Elmet). It is known, from the poetic sources, that under Urien's leadership the kings of the north fought against the encroaching Angles of Bernicia and that he was betrayed by one of his own allies, Morcant Bulc, who arranged his assassination after the battle of Ynys Metcaut (Lindisfarne) around 585 AD.

The Battle of Catraeth, fought by the British (c. 600 AD) to try to recover Catraeth after Urien's death, was a disastrous defeat for them. Aethelfrith, the victor, probably received tribute from the kings of Rheged, Strathclyde and Gododdin (and maybe even from the Scots of Dalriada) thereafter.[92]

Christian saints

One aspect of the sub-Roman period in Cumbria, that is also uncertain as regards its historical evidence, is the early establishment of Christianity. A number of early 'Celtic' saints are associated with the region, including Saint Patrick, Saint Ninian and Saint Kentigern. Whether the dedications to these saints denote a continuance of a Celtic polity or populace through this period and the subsequent Anglian and Scandinavian periods, or whether they are the result of 12th-century revivals of interest in them, is unclear.

Definite evidence of 6th-century Christianity in Cumbria is hard to find – no remains of stone-built churches exist and any wooden ones have disappeared.

Life in 'Dark-age' Cumbria

Despite, or perhaps because of, the emergence of local chieftains and warbands, there are signs that the 5th and 6th centuries were not ones of economic strain in Cumbria (not more than usual, at least).

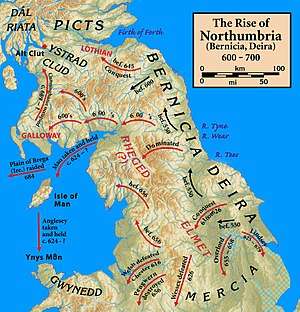

The Angles: Northumbrian takeover and rule, c. 600–875

The 7th century saw the rise to power of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria (just as the 8th saw the rise of Mercia, and the 9th that of Wessex). The Northumbrian kingdom was based on the expansionist power of Bernicia, which, by 604, had taken over their neighbouring kingdom of Deira, along with other kingdoms of the Old North such as Rheged, although the dating of the takeover, and the extent of the Anglo-Saxon settlement that followed, are a matter of contention amongst historians.[93] Documentary and archaeological evidence is lacking and qualified reliance is placed on place-names, sculpture and blood-group studies, all of which are open to challenge.

Takeover

The reign of Aethelfrith's rival, brother-in-law and successor, Edwin, saw Northumbrian power stretch as far as the 'Irish Sea Province' with the taking of the Isle of Man (c. 624) and Anglesey. How much involvement Rheged had in this move is unclear. Northumbrian ambitions were eventually checked with the disastrous defeat of King Ecgfrith's forces in 685 at the hands of the Picts at the Battle of Dun Nechtain, but the north-west region, including the Cumbria area, remained firmly within the Northumbrian ambit during this period.

Around 638 AD Oswiu, who would become the King of Northumbria after the death of Oswald, married Riemmelth (Rhiainfellt), a direct descendant of Urien Rheged and a Princess of the kingdom. This peaceable alliance between the British and English signalled the beginning of the end of formal Cumbrian independence, as Angles from the north east began to filter into the Eden Valley and along the north and south coasts of the county.

Anglian settlement

The extent of Anglian settlement of Cumbria during this period is unclear. The place-name evidence suggests that Old English (that is, Anglo-Saxon, or, in this case, Anglian) names are to be found in the lower-lying areas around the highland (modern Lake District) inner-core.

At least one historian [94] believes that the core, strategically important, area of the Solway and the lower Eden valley, remained essentially 'Celtic', with Carlisle retaining its old Roman 'civitas' status under Northumbrian overlordship, occasionally visited by the King of Northumbria and bishops such as Cuthbert, and overseen by a 'praepositus' (English: 'reeve'), a kind of permanent official. Also, " ...many inhabitants" continued to speak Cumbric "throughout the Bernician occupation." The exceptions, more colonised by the Northumbrian English than the rest of the Cumbrian region, were perhaps the following: a) the upper Eden valley; b) the area to the east of the western edge of Bernicia; c) the Cumbrian coast, probably settled from the sea; d) the south, which may have been subject to Wilfrid's attentions, and Cartmel which was given to Cuthbert.

(Some historians, however, do not see the praepositus official as evidence of permanent, Celtic, occupation).[95]

King Edwin, according to the Historia Brittonum, was converted to Christianity by Rhun, son of Urien, around 628. However, Bede states that Bishop Paulinus was the main force behind this. Rhun was probably present regularly at Edwin's court as a representative of Rheged. Later, the Bernician over-king, Oswiu (643–671), married twice – firstly Riemmelth of Rheged (granddaughter of Rhun), and secondly Eanflaed of Deira, thus uniting all three kingdoms. It is thus possible that a line of Anglian sub-kings ruled at Carlisle, from this time on, at least, on the strength of legal title and not just conquest.[96]

In 670, Oswiu's son—but not by Riemmelth—Ecgfrith ascended the throne of Northumbria and it was possibly in that year that the Bewcastle Cross was erected, bearing English runes, which shows that they were certainly present in the area.).[97] But it seems that Cumbria was little more than a province at this time and, although Anglian influences were clearly seeping in, the region remained essentially British and retained its own client-kings.

Church and state

The relation between church and state may have led to the end of Northumbrian control in the Cumbria region.

Legend has it that Cuthbert foresaw the death of Ecgfrith (at Dun Nechtain), while visiting the church at Carlisle, warning Ecgfrith's (second) wife Eormenburg whom he was accompanying. Bede reckoned that the decline of Northumbrian power dated from this year (685), but military set-backs were only part of the picture. Inter-family struggles amongst the various branches of the royal family played a part, as did the granting of royal estates (the so-called villae) to the Northumbrian Roman church (in return for support for the various attempts on the throne), encouraged by the aristocracy who wished to lessen the burden of royal power and taxation.[98] Cuthbert's grant of lands around Cartmel was one example of this process of degradation of royal resources and power.

The huge estates given to the Church meant that it became an alternative power-base to the king. In Cumbria, there were monasteries at Carlisle, Dacre, and Heversham, known from literary sources; and at Knells, Workington and Beckermet, known from stone inscriptions; and possible sites at Irton, with its early 9th-century cross, Urswick and Addingham without any evidence attached to them.[99] Anglian sculpture was invariably to be found at monastic sites (which, in turn, were to be found in good agricultural areas). The crosses themselves were not grave markers (a few cemeteries had grave slabs), but were "memorials to the saints and to the dead."[100][101]

The rise of the church, and the parallel decline in fortune of the secular royal power, meant that Northumbria and its Cumbrian appendage were not strong enough militarily to fend off the next set of raiders and settlers (who first attacked the Lindisfarne monastery in 793) – the Vikings. By 875, the Northumbrian kingdom had been taken over by Danish Vikings. Cumbria was to go through a period of Irish-Scandinavian (Norse) settlement with the addition, from the late 9th century on, of the influx of more Brittonic Celts.

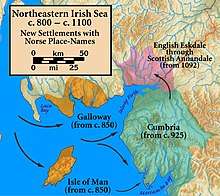

Vikings, Strathclyde British, Scots, English and 'Cumbria', 875–1066

The Norse made devastating raids on the Northumbrian monasteries in the early 800s, and, by 850 had settled in the Western Isles of Scotland, in the Isle of Man, and in the east of Ireland around Dublin. They may have raided or settled in the west coast of Cumbria, although there is no literary or other evidence for this.

The collapse of Anglian authority affected what happened in Cumbria: the power vacuum was filled by the Norse, the Danes in the east, and by the Strathclyde British who themselves came under pressure from the Norse in the 870s and 890s. (The expansion of the Scots to the north and the English to the south also complicates the picture). Once again, our sources for what happened are extremely limited: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, for example, barely mentions the north. We are thrown back upon the study of place-names, artefacts, and stone sculptures, to fill in the picture of 10th-century Cumbria. As a result, there is some dispute amongst historians concerning the timing and the extent of the influx of Vikings and Strathclyders into Cumbria.

Strathclyde British settlement

Some historians argue that the vacuum left by the Northumbrian eclipse in Cumbria led to people from the kingdom of Strathclyde (also confusingly known at this time as 'Cumbria', the 'land of our fellow countrymen' or 'Cymry') moving into the north of what we now call Cumbria. Other historians doubt this scenario, and see the situation as more of a Celtic 'survival' through the 200 years of Anglian Northumbrian rule, rather than a 'revival' based on "a wholly hypothetical process of later re-colonization" by Strathclyders in the 10th century.[102] The bulk of what was to become Cumbria, south of the Eamont, seems to have been untouched by this movement of Brittonic peoples, although a case has been made that all of what was Cumberland, plus Low Furness and part of Cartmel, was under the control, directly or indirectly, of Strathclyde/Cumbria.[103]

It is thought possible that this settlement of fellow Christians was encouraged by the Anglo-Celtic aristocracy, probably with the support of the English south of the Cumbrian region, as a counterweight against the Hiberno-Norse. It may be that, up to around 927, an alliance of Scots, British, Bernicians and Mercians fought against the Norse, who were themselves allied to their fellow Vikings based in York. [104]

This situation altered with the coming of Athelstan to power in England in 927. On 12 July 927, Eamont Bridge (and/or possibly the monastery at Dacre, Cumbria, and/or the site of the old Roman fort at Brougham) was the scene of a gathering of kings from throughout Britain as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the histories of William of Malmesbury and John of Worcester. Present were: Athelstan; Constantín mac Áeda (Constantine II), King of Scots; Owain of Strathclyde, King of the Cumbrians; Hywel Dda, King of Wales; and Ealdred son of Eadulf, Lord of Bamburgh. Athelstan took the submission of some of these other kings, presumably to form some sort of coalition against the Vikings. The growing power of the Scots and perhaps also of the Strathclyders, may have persuaded Athelstan to move north and attempt to define the boundaries of the various kingdoms.[105] This is generally seen as the date of the foundation of the Kingdom of England, the northern boundary of which was the Eamont river (with Westmorland being outside the control of Strathclyde).

However, given the increasing threat from English power, it seems that Strathclyde/Cumbria switched sides and joined with the Dublin Norse to fight the English king who was now in control of Danish Northumbria and presenting a threat to the flank of Cumbrian territory. After the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, (an English victory over the combined Scots, Strathclyders and Hiberno-Norse), Athelstan came to an accommodation with the Scots. During this time, Scandinavian settlement may have been encouraged by the Strathclyde overlords in those areas of Cumbria not already taken by the Anglo-Celtic aristocracy and people.[106]

In 945 Athelstan's successor, Edmund I, invaded Cumbria. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the defeat of the Cumbrians and the harrying of Cumbria (referring not just to the English county of Cumberland but also all the Cumbrian lands up to Glasgow). Edmund's victory was against the last Cumbrian king, known as Dunmail (possibly Dyfnwal III of Strathclyde), and, following the defeat, the area was ceded to Malcolm I, King of Scots, although it is probable that the southernmost areas around Furness, Cartmel and Kendal remained under English control.

Scandinavian settlement

Place-name[107][108][109] and sculptured stone[101][110][111] evidence suggests to one historian that the main Scandinavian colonisation took place on the west coastal plain and in north Westmorland, where some of the better farming land was occupied. The warriors who settled here encouraged stone sculptures to be made. However, the local Anglian peasantry seems to have survived in these areas as well. Some, less successful, occupation of other lowland areas took place, along with, thirdly, occupation of 'waste' land in the lowland and upland areas. This occupation in the less-good farming areas led to place-names in -ǣrgi, -thveit,, -bekkr and -fell, although many of these may have been introduced into the local dialect a long time after the Viking age.[112] "Southern Cumbria", including the future Furness region (Lonsdale Hundred) as well as Amounderness in Lancashire, was also "entensively colonized".[113]

The occupation was likely to have been largely by the Norse between about 900 and 950, but it is unclear whether they were from Ireland, the Western Isles, the Isle of Man, Galloway, or even Norway itself. Just how peaceful, or otherwise, the Scandinavian settlement was remains an open question. It has been suggested that, between c. 850 and 940, the Scots on the one hand, and the Norse of the Hebrides and Dublin on the other, were in collusion as regards what seems to have been peaceful Gaelic-Norse settlement in west Cumbria.[114] It has also been suggested that the Hiberno-Norse in Dublin were prompted to colonise the Cumbrian coast after being temporarily expelled from the city in 902. The successful attempt by Ragnall ua Ímair to conquer the Danes in York (around 920) must have led to the Dublin – York route through Cumbria being frequently used. In Westmorland, it is likely that much colonisation came from Danish Yorkshire, as evidenced by place-names ending in -by in the upper-Eden valley region (around Appleby),[115] especially after the eclipse of Danish power in York in 954 (the year of the death of the Norse King of York, Erik Bloodaxe, on Stainmore).

There was no integrated and organised 'Viking' community in Cumbria – it seems to have been more a case of small groups taking over unoccupied land.[116] (However, others argue that the place-name evidence points to the Scandinavians not just accepting the second-best land, but taking over Anglian vills as well.[117])

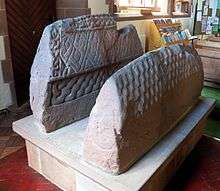

The evidence of the sculpture is unclear when it comes to influences. Although called by some 'pagan' or 'Viking', it may be that some, if not most, of the crosses and hogback sculpture (to be found almost wholly in south Cumbria, away from the Strathclyde area), such as the Gosforth Cross and the Penrith 'Giant's Grave', reflect secular or early Christian concerns, rather than pagan ones.[118]

As an example of Viking relics, a hoard of Viking coins and silver objects was discovered in the Eden valley at Penrith.[119] Also in the Eden valley were finds at Hesket and at Ormside, which has been mentioned above as the site of a possible Viking grave-good. The other areas of Viking finds include Carlisle (west of the Cathedral), pagan graves at Cumwhitton[120] and finds in the Lune valley and on the west coast (for example, Aspatria and St. Michael's Church, Workington).

The Scots and 'Cumbria'

One historian has suggested that the notion of 'Strathclyde/Cumbria' presents too much of a picture of Strathclyde dominating the relationship, and that maybe the Cumbrian area – including the Solway basin and perhaps lands in Galloway, but also specifically the area that became Cumberland county later (the so-called 'Cumbra-land') – was where the prosperity and action lay. It is even suggested that there were two kingships, one of the Clyde area (effectively 'annexed' by Donald II of Scotland in the late 9th century) and another of the Cumbrian (as defined above), the latter having, through marriage or by patronage, increasingly Scottish input.[121] Much of this interpretation rests on the writings of John Fordun and has been challenged by other historians.[122]

Whatever the background, from c. 941, it has been suggested, Cumbrian/Scottish rule may have lasted around 115 years, with territory extending to Dunmail Raise (or 'cairn') in the south of the Cumbrian region (and perhaps Dunmail was trying to extend it through 'Westmoringa land', the future Westmorland, when he incurred the wrath of Edmund I, who regarded the area as English, in 945 ).[123] Edmund, having ravaged Strathclyde/Cumbria, ceded it to the King of Scots, Malcolm I of Scotland, either to define the limits of English rule in the North-West, and/or to secure a treaty with the Scots to prevent them joining up with the Norse and Danes of Dublin and York.[124]

In 971, Kenneth II of Scotland raided 'Westmoringa land', presumably trying to extend the Cumbrian frontier to Stainmore and the Rere Cross. In 973, Kenneth and Máel Coluim I of Strathclyde obtained recognition of this enlarged Cumbria from the English king Edgar. 'Westmoringa land' thus became a buffer zone between the Cumbrian/Scots and the English.

The English and Cumbria

In 1000, the English king, Ethelred the Unready, taking advantage of a temporary absence of the Danes in southern England, invaded Strathclyde/Cumbria for reasons unknown. After the takeover of the English throne by Cnut in 1015/16, the northern region became more disturbed than ever, with the fall of the Bamburgh earls and the defeat of the Northumbrian earl by the Scots and Cumbrians at the Battle of Carham in 1018.[125]

Attempts by the Scots and Cnut to control the area ended with Siward, Earl of Northumbria emerging as a strongman. He was a Dane, becoming Cnut's right-hand man in the north by 1033 (Earl of Yorkshire, around 1033; and also Earl of Northumbria, around 1042). Sometime between 1042 and 1055, Siward seems to have taken control of Cumbria south of the Solway, perhaps responding to pressure from the independent lords of Galloway or from Strathclyde[126] or perhaps taking advantage of Scottish troubles to do with the reign of Macbeth, King of Scotland. The routes through the Tyne Gap and also via the Eden Valley over Stainmore threatened to allow the Scots overlords of Strathclyde/Cumbria to raid Northumbria and Yorkshire respectively (although most Scots' raids took place by crossing the River Tweed into Lothian in the east).

Some evidence comes from a document known to historians as "Gospatric's Writ", one of the earliest documents to do with Cumbrian history.

Siward aided his kinsman Malcolm III of Scotland, possibly known as 'the King of the Cumbrians' (but possibly confused with Owen the Bald of Strathclyde) at the Battle of Dunsinane in 1054, against Macbeth who, although escaping, was eventually killed in 1057. Despite this receipt of help, Malcolm invaded Northumbria in 1061, possibly trying to enforce his claim as 'King of the Cumbrians', (that is, to regain the lost territory of Cumbria south of the Solway taken by Siward), whilst Siward's successor as earl, Tostig Godwinson, was away on pilgrimage. It is likely that Malcolm succeeded in regaining the Cumberland part of Cumbria in 1061: in 1070 he used Cumberland as his base to attack Yorkshire.[128] This 1061 incursion was the first of five such raids by Malcolm, a policy that alienated the English Northumbrians and made it harder to fight the Normans after the invasion of 1066. For the next thirty years, Cumbria, probably down to the Rere Cross boundary, was in the hands of the Scots.[129]

Malcolm III, King of Scots, held the Cumberland territory, (probably down to the River Derwent, River Eamont and Rere Cross on Stainmore line), until 1092, one year before his death in battle. The fact that he did this without challenge was partly the result, as far as the pre-Norman conquest era is concerned, of turmoil and alienation amongst the Northumbrian and Yorkshire nobles, (drawn from the ranks of the old Anglo-Saxon Bamburgh royal family and Danish/Norse nobles respectively), as well as the disaffection of the St. Cuthbert monks (in Durham), due to the rule of the West Saxon outsider Earl Tostig.[130] Other factors include the absentee nature of Tostig's rule in the North, and his friendship with King Malcolm.

High medieval Cumbria, 1066–1272

Norman Cumbria: William I, William 'Rufus', Henry I, and David I, 1066–1153

The Norman takeover of the Cumbria region took place in two phases: the southern district, covering what were to become the baronies of Millom, Furness, Kendale and Lonsdale, were taken over in 1066 (see below under "Domesday"); the northern sector (the "land of Carlisle") was taken over in 1092 by William Rufus.

William I

The Norman conquest of England proceeded only slowly in the North of the country, perhaps due to the relative poverty of the land (for example, not suitable for growing the Normans' preferred wheat, as opposed to oats),[131] and to various uprisings in England as well as in Normandy that meant that William I had to be elsewhere.

The various raids by Malcolm III of Scotland, the Danes and the English rebels, plus regular uprisings by Northumbrian nobles, all contributed to the weakness of William's control of the North. Most of Cumbria therefore remained in the hands of the Scots, as well as being a base for brigands and dispossessed rebels. Cumbria south of the mountains, the future Westmorland south of the Eamont, and North Lancashire, had been held by Tostig in 1065, during which time he had battled against both the Scots and bands of brigands.[132] It is likely that this situation persisted for much of William's reign as well.

William finally brought Northumbria under control: his son, Robert Curthose, building the castle at Newcastle upon Tyne in 1080. Robert de Mowbray's appointment as Earl of Northumbria in 1086, and the building of "castleries" (territories administered by a constable from a castle) in Yorkshire, helped to clear up the brigandage problem.

Domesday

When the Normans conquered England in 1066, much of Cumbria was a no-man's-land between England and Scotland which meant that the land was not of great value. Secondly, when the Domesday Book was compiled (1086), Cumbria had not been conquered by the Normans. Only the southern part of the county, (the Millom, Furness, and part, or all, of Cartmel peninsulas), known as the Manor of Hougun, that which included lands held by Earl Tostig, was included, and even that was only as annexes to the Yorkshire entry.(There is some doubt as to whether Hougun was indeed an administrative district, or merely the chief vill in Furness and Copeland under which the other vills were listed).[133]

William II

William II of England (William "Rufus") recognised that the state of affairs, as left to him by William I in 1087, was only a holding solution to the problems of the unsatisfactory position of the Normans above the Humber in the East and above the Ribble to the West.

In 1092, Rufus took over Cumberland by expelling the local lord, Dolfin, (who may or may not have been related to Earl Cospatrick).[134][135] Then, he built the castle at Carlisle and garrisoned it with his own men, and sent peasants, possibly from Ivo Taillebois' Lincolnshire lands, to cultivate the land there.[136] The takeover of the Carlisle area was probably to do with gaining territory and providing a strongpoint to defend his north-west frontier.[137] Kapelle suggests that the takeover of Cumberland and the building at Carlisle may have been designed to humiliate King Malcolm or to provoke him into battle.[138] The result was the last invasion by Malcolm and his own, plus his son's, death at the Battle of Alnwick (1093). The subsequent contest for the succession to the Scottish throne (between Donald II of Scotland and Edgar, King of Scotland) allowed Rufus to maintain his hold on the Cumberland and Carlisle areas until his death in 1100.

Henry I

A step-change occurred in the governance of the Cumbria area with the succession of Henry I of England. Henry enjoyed good relations with both Alexander I of Scotland and Henry's nephew, David I of Scotland, and therefore he could concentrate on developing his northern lands without the threat of a Scottish invasion.[139] Either he or his predecessor, Rufus, possibly around 1098, granted Appleby and Carlisle to Ranulf le Meschin who became the strongman of the north-west frontier.[140] (Others place the date of the grants after the Battle of Tinchebrai, that is, 1106 onwards).[141] Ranulf was the third husband of Lucy of Bolingbroke, the first husband of whom had been Ivo Taillebois, whose Cumbrian and Lincolnshire lands he inherited.

Henry I himself visited Carlisle the following year, from October or November 1122. While there, he ordered the castle to be fortified and created "several tenures that would come to be regarded as baronies" : William Meschin in Copeland (where William built Egremont Castle); Waltheof, son of Gospatrick in Allerdale; Forn, son of Sigulf, in Greystoke; Odard, the sheriff, in Wigton; Richard de Boivill in Kirklinton.[142] There is some doubt as to whether these enfeoffments were new or whether they were confirmations of tenants-in-chief under Ranulf's previous administration. Sharpe argues that Henry did not create "the institutions of county government" when he took charge directly.[143]

Henry also took direct control (perhaps in the years after 1122) in Carlisle partly in order to ensure that the running of the silver mine at Alston was done from there. He also confirmed the property and rights of the monks of Wetheral; and he established the Augustinian priory of Saint Mary at Carlisle, becoming, in 1133, Carlisle Cathedral when a new diocese was created.

Henry, besides promoting his Norman allies into positions of power in the north, was also careful to install some local lords into secondary roles. For example, two Anglo-Saxon northerners, probably from Yorkshire, were Æthelwold, who became the first Bishop of Carlisle, and Forn of Greystoke. Waltheof of Allerdale was a Northumbrian.[144]

David I of Scotland

With the death of Henry I in 1135, England fell into a civil war, known as The Anarchy. Stephen of Blois contested the English crown with Henry's daughter, Matilda (or Maude). David I of Scotland, who was Prince of the Cumbrians (1113–1124), and Earl of Northampton and Huntingdon, had been King of Scots since 1124. Having been brought up in the court of his mentor and uncle, Henry I, as very much a Norman prince, he supported the claims of Matilda over those of her cousin, Stephen of Blois.

Professor Barrow asserts that, even at the beginning of his reign, David was thinking of the lands of Carlisle and Cumberland, believing, as he did, that "Cumbria" (that is, the previous entity of Strathclyde/Cumbria, covered by the diocese of Glasgow) was under the overlordship of the King of Scots, and stretched as far as Westmorland and possibly down to north Lancashire or even to the River Ribble.[145] The (first) Treaty of Durham (1136) ceded Carlisle and Cumberland to David.

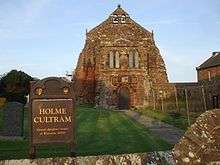

David may have been intending to enlarge his control of northern England when he fought at the Battle of the Standard, some of the soldiers of David's force being Cumbrians (from south of the Solway-Esk line, that is). Despite losing the battle, David kept his Cumbrian lands, and his son Henry was made Earl of Northumberland at the (second) Treaty of Durham (1139). This arrangement lasted another twenty years, during which David minted his own coins using the silver from the Alston mines, founded the abbey at Holm Cultram, kept the north largely out of the civil war of Stephen and Matilda, and, by the "Carlisle settlement" of 1149, obtained a promise from Henry of Anjou that, upon the latter's becoming King of England, he would not challenge the King of Scots's rule over Carlisle and Cumberland. David died at Carlisle in 1153, a year after his son Henry.

Cumbria under the early Angevins, 1154–1272

Henry II, 1154–89

The pattern of trading upon the weakness of one side or the other continued as regards Anglo-Scottish relations in 1154 when Henry of Anjou became King of England. (The Angevins were also known, from 1204 on, as the Plantagenets). King David of Scotland's death left an eleven-year-old boy, Malcolm IV, on the Scottish throne. Malcolm had inherited the earldoms of Cumbria (and Northumbria) as fiefs of the English crown, and did homage to Henry for them. However, at Chester, in July 1157, Henry demanded, and obtained, the return of control to England of Cumbria and Northumberland. The King of Scots was given the honours of Huntingdon and Tynedale in return, and relations between the two countries were amicable enough, although Henry and Malcolm seem to have fallen out at another meeting in Carlisle in June 1158, according to Roger of Hoveden.[146]

Henry took the opportunity of this relative peace to increase royal control in the north: justices toured the remote northern areas, taxes were collected and order was maintained. Hubert I de Vaux was given the Barony of Gilsland in order to strengthen defences.[147] The accession to the Scottish throne of William the Lion in 1165 brought border wars, (the war of 1173–74 saw Carlisle besieged twice by the Scottish king's forces, with the city being surrendered by the constable of Carlisle Castle, Robert de Vaux, when food ran out), but no giving up of Cumbria (or Northumberland) to the Scots, despite Henry's troubles after the murder of Thomas Becket and the Scots' alliance with France. The Treaty of Falaise of 1174 formalised a rather coercive peace between the two countries.[148]