Henry VI of England

Henry VI (6 December 1421 – 21 May 1471) was King of England from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. The only child of Henry V, he succeeded to the English throne at the age of nine months upon his father's death, and succeeded to the French throne on the death of his maternal grandfather, Charles VI, shortly afterwards.

| Henry VI | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| King of England (more...) | |

| Reign | 1 September 1422 – 4 March 1461 |

| Coronation | 6 November 1429, Westminster Abbey |

| Predecessor | Henry V |

| Successor | Edward IV |

| Regents |

|

| King of France (disputed) | |

| Reign | 21 October 1422 – 19 October 1453 |

| Coronation | 16 December 1431, Notre-Dame de Paris |

| Predecessor | Charles VI |

| Successor | Charles VII |

| Regent |

|

| King of England (more...) | |

| Reign | 3 October 1470 – 11 April 1471 |

| Predecessor | Edward IV |

| Successor | Edward IV |

| Born | 6 December 1421 Windsor Castle, Berkshire, England |

| Died | 21 May 1471 (aged 49) Tower of London, London, England |

| Burial | 12 August 1484 |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | Edward, Prince of Wales |

| House | Lancaster (Plantagenet) |

| Father | Henry V of England |

| Mother | Catherine of Valois |

| Signature |  |

Henry inherited the long-running Hundred Years' War (1337–1453), in which his uncle Charles VII contested his claim to the French throne. He is the only English monarch to also have been crowned King of France (as Henry II, in 1431). His early reign, when several people were ruling for him, saw the pinnacle of English power in France, but subsequent military, diplomatic, and economic problems had seriously endangered the English cause by the time Henry was declared fit to rule in 1437. He found his realm in a difficult position, faced with setbacks in France and divisions among the nobility at home. Unlike his father, Henry is described as timid, shy, passive, well-intentioned, and averse to warfare and violence; he was also at times mentally unstable. His ineffective reign saw the gradual loss of the English lands in France. Partially in the hope of achieving peace, in 1445 Henry married Charles VII's niece, the ambitious and strong-willed Margaret of Anjou. The peace policy failed, leading to the murder of one of Henry's key advisers, William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, and the war recommenced, with France taking the upper hand; by 1453, Calais was Henry's only remaining territory on the continent.

As the situation in France worsened, there was a related increase in political instability in England. With Henry effectively unfit to rule, power was exercised by quarrelsome nobles, while factions and favourites encouraged the rise of disorder in the country. Regional magnates and soldiers returning from France formed and maintained increasing numbers of private armed retainers, with whom they fought one another, terrorised their neighbours, paralysed the courts, and dominated the government.[1] Queen Margaret did not remain unpartisan, and took advantage of the situation to make herself an effective power behind the throne.

Amidst military disasters in France and a collapse of law and order in England, the Queen and her clique came under accusations, especially from Henry VI's increasingly popular cousin Richard, Duke of York, of misconduct of the war in France and misrule of the country. Starting in 1453, Henry had a series of mental breakdowns, and tensions mounted between Margaret and Richard of York over control of the incapacitated King's government, and over the question of succession to the English throne. Civil war broke out in 1455, leading to a long period of dynastic conflict known as the Wars of the Roses. Henry was deposed on 29 March 1461 after a crushing defeat at the Battle of Towton by Richard's son, who took the throne as Edward IV. Despite Margaret continuing to lead a resistance to Edward, Henry was captured by Edward's forces in 1465 and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Henry was restored to the throne in 1470, but Edward retook power in 1471, killing Henry's only son and heir, Edward of Westminster, in battle and imprisoning Henry once again.

Having "lost his wits, his two kingdoms, and his only son",[2] Henry died in the Tower during the night of 21 May, possibly killed on the orders of King Edward. Miracles were attributed to Henry after his death, and he was informally regarded as a saint and martyr until the 16th century. He left a legacy of educational institutions, having founded Eton College, King's College, Cambridge, and (together with Henry Chichele) All Souls College, Oxford. Shakespeare wrote a trilogy of plays about his life, depicting him as weak-willed and easily influenced by his wife, Margaret.

Child king

Henry was the only child and heir of King Henry V. He was born on 6 December 1421 at Windsor Castle. He succeeded to the throne as King of England at the age of nine months on 1 September 1422, the day after his father's death;[3] he was the youngest person ever to succeed to the English throne. On 21 October 1422, in accordance with the Treaty of Troyes of 1420, he became titular King of France upon his grandfather Charles VI's death. His mother, the 20-year-old Catherine of Valois, was viewed with considerable suspicion by English nobles as Charles VI's daughter. She was prevented from playing a full role in her son's upbringing.

On 28 September 1423, the nobles swore loyalty to Henry VI, who was not yet two years old. They summoned Parliament in the King's name and established a regency council to govern until the King should come of age. One of Henry V's surviving brothers, John, Duke of Bedford, was appointed senior regent of the realm and was in charge of the ongoing war in France. During Bedford's absence, the government of England was headed by Henry V's other surviving brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, who was appointed Lord Protector and Defender of the Realm. His duties were limited to keeping the peace and summoning Parliament. Henry V's uncle Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester (after 1426 also Cardinal), had an important place on the Council. After the Duke of Bedford died in 1435, the Duke of Gloucester claimed the Regency himself, but was contested in this by the other members of the Council.

From 1428, Henry's tutor was Richard de Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, whose father had been instrumental in the opposition to Richard II's reign. For the period 1430–1432, Henry was also tutored by the physician John Somerset. Somerset's duties were to 'tutor the young king as well as preserving his health'.[4] Somerset remained within the royal household until early 1451 after the English House of Commons petitioned for his removal because of his 'dangerous and subversive influence over Henry VI'.[5]

Henry's mother Catherine remarried to Owen Tudor and had two sons by him, Edmund and Jasper. Henry later gave his half-brothers earldoms. Edmund Tudor was the father of King Henry VII of England.

In reaction to the coronation of Charles VII of France in Reims Cathedral on 17 July 1429,[6] Henry was soon crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey on 6 November 1429,[7] aged 7, followed by his own coronation as King of France at Notre Dame de Paris on 16 December 1431, aged 10.[7] He was the only English king to be crowned king in both England and France. It was shortly after his crowning ceremony at Merton Priory on All Saints' Day, 1 November 1437,[8] shortly before his 16th birthday, that he obtained some measure of independent authority. This was confirmed on 13 November 1437,[9] but his growing willingness to involve himself in administration had already became apparent in 1434, when the place named on writs temporarily changed from Westminster (where the Privy Council met) to Cirencester (where the King resided).[10] He finally assumed full royal powers when he came of age at the end of the year 1437, when he turned sixteen years old.[11] Henry's assumption of full royal powers occurred during the Great Bullion Famine and the beginning of the Great Slump in England.

Assumption of government and French policies

Henry, who was by nature shy, pious, and averse to deceit and bloodshed, immediately allowed his court to be dominated by a few noble favourites who clashed on the matter of the French war when he assumed the reins of government in 1437. After the death of King Henry V, England had lost momentum in the Hundred Years' War, whereas the House of Valois had gained ground beginning with Joan of Arc's military victories in the year 1429. The young King came to favour a policy of peace in France and thus favoured the faction around Cardinal Beaufort and William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, who thought likewise; the Duke of Gloucester and Richard, Duke of York, who argued for a continuation of the war, were ignored.

Marriage

As the English military situation in France deteriorated, talks emerged in England about arranging a marriage for the King to strengthen England's foreign connections[12] and facilitate a peace between the warring parties. In 1434, the English council suggested that peace with the Scots could best be effected by wedding Henry to one of the daughters of King James I of Scotland; the proposal came to nothing. During the Congress of Arras in 1435, the English put forth the idea of a union between Henry and a daughter of King Charles VII of France, but the Armagnacs refused even to contemplate the suggestion unless Henry renounced his claim to the French throne. Another proposal in 1438 to a daughter of King Albert II of Germany likewise failed.[12]

Better prospects for England arose amidst a growing effort by French lords to resist the growing power of the French monarchy, a conflict which culminated in the Praguerie revolt of 1440.[12] Though the English failed to take advantage of the Praguerie itself, the prospect of gaining the allegiance of one of Charles VII's more rebellious nobles was attractive from a military perspective. In about 1441, the recently ransomed Charles, Duke of Orléans, in an attempt to force Charles VII to make peace with the English, suggested a marriage between Henry VI and a daughter of John IV, Count of Armagnac,[13] a powerful noble in southwestern France who was at odds with the Valois crown.[14] An alliance with Armagnac would have helped to protect English Gascony from increasing French threats in the region, especially in the face of defections to the enemy by local English vassals,[15] and might have helped to wean some other French nobles to the English party.[16] The proposal was seriously entertained between 1441 and 1443, but a massive French campaign in 1442 against Gascony disrupted the work of the ambassadors[17] and frightened the Count of Armagnac into reluctance.[18] The deal fell through due to problems in commissioning portraits of the Count's daughters[19] and the Count's imprisonment by Charles VII's men in 1443.[20]

Cardinal Beaufort and the Earl of Suffolk persuaded Henry that the best way to pursue peace with France was through a marriage with Margaret of Anjou, the niece of King Charles VII. Henry agreed, especially when he heard reports of Margaret's stunning beauty, and sent Suffolk to negotiate with Charles, who consented to the marriage on condition that he would not have to provide the customary dowry and instead would receive the province of Maine from the English. These conditions were agreed in the Treaty of Tours in 1444, but the cession of Maine was kept secret from Parliament, as it was known that this would be hugely unpopular with the English populace. The marriage took place at Titchfield Abbey on 23 April 1445, one month after Margaret's 15th birthday. She had arrived with an established household, composed primarily not of Angevins, but of members of Henry's royal servants; this increase in the size of the royal household, and a concomitant increase on the birth of their son, Edward of Westminster, in 1453, led to proportionately greater expense but also to greater patronage opportunities at Court.[21]

Henry had wavered in yielding Maine to Charles, knowing that the move was unpopular and would be opposed by the Dukes of Gloucester and York, and also because Maine was vital to the defence of Normandy. However, Margaret was determined that he should see it through. As the treaty became public knowledge in 1446, public anger focused on the Earl of Suffolk, but Henry and Margaret were determined to protect him.

Ascendancy of Suffolk and Somerset

In 1447, the King and Queen summoned the Duke of Gloucester to appear before parliament on the charge of treason. Queen Margaret had no tolerance for any sign of disloyalty towards her husband and kingdom, thus any suspicion of this was immediately brought to her attention. This move was instigated by Gloucester's enemies, the Earl of Suffolk, whom Margaret held in great esteem, and the aging Cardinal Beaufort and his nephew, Edmund Beaufort, Earl of Somerset. Gloucester was put in custody in Bury St Edmunds, where he died, probably of a heart attack (although contemporary rumours spoke of poisoning) before he could be tried.[lower-alpha 2]

The Duke of York, being the most powerful duke in the realm, and also being both an agnate and the heir general of Edward III (thus having, according to some, a better claim to the throne than Henry VI himself), probably had the best chances to succeed to the throne after Gloucester. However, he was excluded from the court circle and sent to govern Ireland, while his opponents, the Earls of Suffolk and Somerset, were promoted to Dukes, a title at that time still normally reserved for immediate relatives of the monarch.[22] The new Duke of Somerset was sent to France to assume the command of the English forces; this prestigious position was previously held by the Duke of York himself, who was dismayed at his term not being renewed and at seeing his enemy take control of it.

In the later years of Henry's reign, the monarchy became increasingly unpopular, due to a breakdown in law and order, corruption, the distribution of royal land to the King's court favourites, the troubled state of the crown's finances, and the steady loss of territories in France. In 1447, this unpopularity took the form of a Commons campaign against William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, who was the most unpopular of all the King's entourage and widely seen as a traitor. He was impeached by Parliament to a background that has been called "the baying for Suffolk’s blood [by] a London mob",[23] to the extent that Suffolk admitted his alarm to Henry.[24] Ultimately, Henry was forced to send him into exile, but Suffolk's ship was intercepted in the English Channel. His murdered body was found on the beach at Dover.[25]

In 1449, the Duke of Somerset, leading the campaign in France, reopened hostilities in Normandy (although he had previously been one of the main advocates for peace), but by the autumn he had been pushed back to Caen. By 1450, the French had retaken the whole province, so hard won by Henry V. Returning troops, who had often not been paid, added to the lawlessness in the southern counties of England. Jack Cade led a rebellion in Kent in 1450, calling himself "John Mortimer", apparently in sympathy with York, and setting up residence at the White Hart Inn in Southwark (the white hart had been the symbol of the deposed Richard II).[26] Henry came to London with an army to crush the rebellion, but on finding that Cade had fled kept most of his troops behind while a small force followed the rebels and met them at Sevenoaks. The flight proved to have been tactical: Cade successfully ambushed the force in the Battle of Solefields (near Sevenoaks) and returned to occupy London. In the end, the rebellion achieved nothing, and London was retaken after a few days of disorder; but this was principally because of the efforts of its own residents rather than those of the army. At any rate the rebellion showed that feelings of discontent were running high.[27]

In 1451, the Duchy of Aquitaine, held by England since Henry II's time, was also lost. In October 1452, an English advance in Aquitaine retook Bordeaux and was having some success, but by 1453 Bordeaux was lost again, leaving Calais as England's only remaining territory on the continent.

Insanity, and the ascendancy of York

.jpg)

In 1452, the Duke of York was persuaded to return from Ireland, claim his rightful place on the council and put an end to bad government. His cause was a popular one and he soon raised an army at Shrewsbury. The court party, meanwhile, raised their own similar-sized force in London. A stand-off took place south of London, with York presenting a list of grievances and demands to the court circle, including the arrest of Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset. The King initially agreed, but Margaret intervened to prevent the arrest of Beaufort. By 1453, Somerset's influence had been restored, and York was again isolated. The court party was also strengthened by the announcement that the Queen was pregnant.

However, on hearing of the final loss of Bordeaux in August 1453, Henry experienced a mental breakdown and became completely unresponsive to everything that was going on around him for more than a year.[28] He even failed to respond to the birth of his son Edward. Henry may have inherited a psychiatric condition from Charles VI of France, his maternal grandfather, who was affected by intermittent periods of insanity during the last thirty years of his life.[lower-alpha 3] During his bout of insanity, Henry was attended by the surgeons Gilbert Kymer and John Marchall. Thomas Morstede had previously been appointed royal surgeon and died in 1450.

The Duke of York, meanwhile, had gained a very important ally, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, one of the most influential magnates and possibly richer than York himself. York was named regent as Protector of the Realm in 1454. The Queen was excluded completely, and Edmund Beaufort was detained in the Tower of London, while many of York's supporters spread rumours that Edward was not the King's son, but Beaufort's.[29] Other than that, York's months as regent were spent tackling the problem of government overspending.[30]

Wars of the Roses

_obverse.jpg)

Around Christmas Day 1454, King Henry regained his senses. Disaffected nobles who had grown in power during Henry's reign, most importantly the Earls of Warwick and Salisbury, took matters into their own hands. They backed the claims of the rival House of York, first to the control of government, and then to the throne itself (from 1460), pointing to York's better descent from Edward III. It was agreed that York would become Henry's successor, despite York being older.[30] In 1458, in an attempt to unite the warring factions, Henry staged The Love Day in London.

There followed a violent struggle between the houses of Lancaster and York. Henry was defeated and captured at the Battle of Northampton on 10 July 1460. The Duke of York was killed by Margaret's forces at the Battle of Wakefield on 30 December 1460, and Henry was rescued from imprisonment after the Second Battle of St Albans on 17 February 1461. By then, however, Henry was suffering such a bout of madness that he was apparently laughing and singing while the battle raged. He was defeated at the Battle of Towton on 29 March 1461 by the Duke of York's son, Edward, who then became King Edward IV. Edward failed to capture Henry and his wife, who fled to Scotland. During the first period of Edward IV's reign, Lancastrian resistance continued mainly under the leadership of Queen Margaret and the few nobles still loyal to her in the northern counties of England and Wales.

Following his defeat in the Battle of Hexham on 15 May 1464, Henry found refuge, sheltered by Lancastrian supporters, at houses across the north of England. By July 1465, he was in hiding at Waddington Hall, in Waddington, Lancashire, the home of Sir Richard Tempest. Here, he was betrayed by "a black monk of Addington" and on 13 July, a group of Yorkist men, including Sir Richard's brother John, entered the home to arrest him. Henry fled into nearby woods, but was soon captured at Brungerley Hippings (stepping stones) over the River Ribble.[31] He was subsequently held captive in the Tower of London.[32][33]

While imprisoned, Henry did some writing, including the following poem:

Kingdoms are but cares

State is devoid of stay,

Riches are ready snares,

And hasten to decay

Pleasure is a privy prick

Which vice doth still provoke;

Pomps, imprompt; and fame, a flame;

Power, a smoldering smoke.

Who meanth to remove the rock

Owst of the slimy mud

Shall mire himself, and hardly scape

The swelling of the flood.<ref name="FOOTNOTECheetham200069">Cheetham 2000, p. 69.</ref>

Return to the throne

Queen Margaret, exiled in Scotland and later in France, was determined to win back the throne on behalf of her husband and her son, Edward of Westminster. By herself, there was little she could do. However, eventually Edward IV fell out with two of his main supporters: Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, and his own younger brother George, Duke of Clarence. At the urging of King Louis XI of France they formed a secret alliance with Margaret. After marrying his daughter Anne to Henry and Margaret's son, Warwick returned to England, forced Edward IV into exile, and restored Henry VI to the throne on 3 October 1470; the term "readeption" is still sometimes used for this event. However, by this time, years in hiding followed by years in captivity had taken their toll on Henry. Warwick and Clarence effectively ruled in his name.[34]

Henry's return to the throne lasted less than six months. Warwick soon overreached himself by declaring war on Burgundy, whose ruler responded by giving Edward IV the assistance he needed to win back his throne by force. Edward returned to England in early 1471, after which he was reconciled with Clarence and killed Warwick at the Battle of Barnet. The Yorkists won a final decisive victory at the Battle of Tewkesbury on 4 May 1471, where Henry's son Edward of Westminster was killed.[lower-alpha 4]

Imprisonment and death

Henry was imprisoned in the Tower of London again, and when the royal party arrived in London, he was reported dead. Official chronicles and documents state that the deposed king died on the night of 21 May 1471. In all likelihood, his opponents had kept him alive up to this point rather than leave the Lancasters with a far more formidable leader in Henry's son, Edward. However, once the last of the most prominent Lancastrian supporters were either killed or exiled, it became clear that Henry VI would be a burden to Edward IV's reign. The common fear was the possibility of another noble using the mentally unstable king to further their own agenda.

According to the Historie of the arrivall of Edward IV, an official chronicle favourable to Edward IV, Henry died of melancholy on hearing news of the Battle of Tewkesbury and his son's death.[35] It is widely suspected, however, that Edward IV, who was re-crowned the morning following Henry's death, had in fact ordered his murder.[lower-alpha 5]

Sir Thomas More's History of Richard III explicitly states that Richard killed Henry, an opinion he might have derived from Philippe de Commines' Memoir.[37] Another contemporary source, Wakefield's Chronicle, gives the date of Henry's death as 23 May, on which date Richard is known to have been away from London.

Modern tradition places his death at Wakefield Tower, a building of the Tower of London, but this is not supported by evidence, and is unlikely, since the tower was used for record storage at the time. Henry's place of death is unknown, though he was imprisoned within the Tower of London.[38]

King Henry VI was originally buried in Chertsey Abbey; then, in 1484, his body was moved to St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, by Richard III. When Henry's body was exhumed in 1910, it was found to be 5 ft 9 inches (1.75 m) tall. Light hair had been found to be covered in blood, with damage to the skull, strongly suggesting that the king had indeed died due to violence.[39]

Legacy

Architecture and education

Henry's one lasting achievement was his fostering of education: he founded Eton College, King's College, Cambridge and All Souls College, Oxford. He continued a career of architectural patronage started by his father: King's College Chapel and Eton College Chapel and most of his other architectural commissions (such as his completion of his father's foundation of Syon Abbey) consisted of a late Gothic or Perpendicular-style church with a monastic or educational foundation attached. Each year on the anniversary of Henry VI's death, the Provosts of Eton and King's lay white lilies and roses, the respective floral emblems of those colleges, on the spot in the Wakefield Tower at the Tower of London where the imprisoned Henry VI was, according to tradition, murdered as he knelt at prayer. There is a similar ceremony at his resting place, St George's Chapel.[40]

Posthumous cult

Miracles were attributed to Henry, and he was informally regarded as a saint and martyr, addressed particularly in cases of adversity. The anti-Yorkist cult was encouraged by Henry VII of England as dynastic propaganda. A volume was compiled of the miracles attributed to him at St George's Chapel, Windsor, where Richard III had reinterred him, and Henry VII began building a chapel at Westminster Abbey to house Henry VI's relics.[41] A number of Henry VI's miracles possessed a political dimension, such as his cure of a young girl afflicted with the King's evil, whose parents refused to bring her to the usurper, Richard III.[42] By the time of Henry VIII's break with Rome, canonisation proceedings were under way.[43] Hymns to him still exist, and until the Reformation his hat was kept by his tomb at Windsor, where pilgrims would put it on to enlist Henry's aid against migraines.[44]

Numerous miracles were credited to the dead king, including his raising the plague victim Alice Newnett from the dead and appearing to her as she was being stitched in her shroud.[45] He also intervened in the attempted hanging of a man who had been unjustly condemned to death, accused of stealing some sheep. Henry placed his hand between the rope and the man's windpipe, thus keeping him alive, after which he revived in the cart as it was taking him away for burial.[46] He was also capable of inflicting harm, such as when he struck John Robyns blind after Robyns cursed "Saint Henry". Robyns was healed only after he went on a pilgrimage to the shrine of King Henry.[47] A particular devotional act that was closely associated with the cult of Henry VI was the bending of a silver coin as an offering to the "saint" in order that he might perform a miracle. One story had a woman, Katherine Bailey, who was blind in one eye. As she was kneeling at mass, a stranger told her to bend a coin to King Henry. She promised to do so, and as the priest was raising the communion host, her partial blindness was cured.[48]

Although Henry VI's shrine was enormously popular as a pilgrimage destination during the early decades of the 16th century,[49] over time, with the lessened need to legitimise Tudor rule, his cult faded.[50]

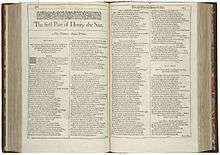

Shakespeare's Henry VI and after

In 1590 William Shakespeare wrote a trilogy of plays about the life of Henry VI: Henry VI, Part 1, Henry VI, Part 2, and Henry VI, Part 3. His dead body and his ghost also appear in Richard III. Shakespeare's portrayal of Henry is notable in that it does not mention the King's madness. This is considered to have been a politically-advisable move so as to not risk offending Elizabeth I whose family was descended from Henry's Lancastrian family. Instead Henry is portrayed as a pious and peaceful man ill-suited to the crown. He spends most of his time in contemplation of the Bible and expressing his wish to be anyone other than a king. Shakespeare's Henry is weak-willed and easily influenced allowing his policies to be led by Margaret and her allies, and being unable to defend himself against York's claim to the throne. He only takes an act of his own volition just before his death when he curses Richard of Gloucester just before he is murdered.

In screen adaptations of these plays Henry has been portrayed by: James Berry in the 1911 silent short Richard III; Terry Scully in the 1960 BBC series An Age of Kings which contained all the history plays from Richard II to Richard III; Carl Wery in the 1964 West German TV version König Richard III; David Warner in The Wars of the Roses, a 1965 filmed version of the Royal Shakespeare Company performing the three parts of Henry VI (condensed and edited into two plays, Henry VI and Edward IV) and Richard III; Peter Benson in the 1983 BBC version of all three parts of Henry VI and Richard III; Paul Brennen in the 1989 film version of the full cycle of consecutive history plays performed, for several years, by the English Shakespeare Company; Edward Jewesbury in the 1995 film version of Richard III with Ian McKellen as Richard; James Dalesandro as Henry in the 2008 modern-day film version of Richard III; and Tom Sturridge as Henry to Benedict Cumberbatch's Richard III in the 2016 second BBC series The Hollow Crown, an adaptation of Henry VI (condensed into two parts) and Richard III. Miles Mander portrayed him in Tower of London, a 1939 horror film loosely dramatising the rise to power of Richard III.

Arms

As Duke of Cornwall, Henry's arms were those of the kingdom, differenced by a label argent of three points.[51]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Henry VI of England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Originally interred at Chertsey Abbey, Surrey.

- With the King's only remaining uncle dead, there were many, though no obvious, candidates to succeed Henry VI to the throne if he died childless. Henry VI's grandfather Henry IV had inaugurated a trend of favouring male succession by his deposition of Richard II in 1399. By this logic, the most senior candidate in the royal family, through male line descent from Edward III, was Richard of York, or his rival Edmund Beaufort (the Earl of Somerset) in case the Beaufort line was declared eligible to succeed (Henry IV had barred them from succession due to their initial illegitimacy). Through primogeniture however, which was the traditional method of English succession, the legitimate successor would be Afonso V of Portugal through his descent from Henry IV's eldest sister, but his status as a foreign monarch made him very unlikely to become king. An alternative line of succession would be the descendants of Henry IV's second sister, whose son was John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter. A fifth candidate to the throne was Margaret Beaufort, who was the heir general of the House of Lancaster (through Henry IV's semi-legitimate brother, John Beaufort), if the Beaufort family was admitted into the succession line. She would later marry Henry VI's maternal half-brother Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond, and originate the Tudor claim to the throne.

- Charles VI, in turn, may have inherited a condition from his mother, Joanna of Bourbon, who also showed signs of mental illness, or other members of her family, who showed signs of psychiatric instability, such as Joanna's father, Peter I, Duke of Bourbon, and her grandfather, Louis I, Duke of Bourbon. Joanna's brother Louis II, Duke of Bourbon, is also reported to have exhibited symptoms of such a condition.

- The manner of the prince's death is one of historical speculation. See: Desmond Seward. "The Wars of the Roses", and Charles Ross, "Wars of the Roses". Both retell the traditional story that the prince sought sanctuary in Tewkesbury Abbey and was dragged out and butchered in the street.

- Either, that with Prince Edward's death, there was no longer any reason to keep Henry alive, or that, until Prince Edward died, there was little benefit to killing Henry. According to rumours at the time, which persisted for many years, Henry VI was killed by a blow to the back of the head, whilst at prayer in the late hours of 21 May 1471.[36]

References

- Cram, Paul (1948). "Western Europe". In William L. Langer (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (revised ed.). Cambridge: Riverside Press. p. 270.

- Cheetham 2000, p. 44.

- Lambert, David; Gray, Randal (1991). Kings and Queens. Collins Gem.

- Rawcliffe, Carole. "Somerset, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Rawcliffe, Carole (1988). "The Profits of Practice: The Wealth and Status of Medical Men in Later Medieval England". Social History of Medicine. 1 (1): 71. doi:10.1093/shm/1.1.61.

- Kendall, Paul Murray (1971). Louis XI: The Universal Spider. New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 39–40. ISBN 9780393053807.

- Allmand 1982.

- Heales, Alfred (1898). The Records of Merton Priory. London: Henry Frowde. p. 299.

- Lingard, J. (1854). A History of England. 5 (new ed.). Boston: Phillips, Sampson and Company. p. 107. hdl:2027/miun.aba0086.0005.001.

- Wolffe 2001, pp. 79–80; apparently this "caused its own crisis of confidence... 'motions and stirrings' had been made"

- Lingard, p. 108.

- Tout 1891, p. 58.

- Tout 1891, p. 59.

- Dicks 1967, pp. 5–6.

- Griffiths 1981, p. 461.

- Griffiths 2015.

- Dicks 1967, pp. 9, 11.

- Dicks 1967, p. 11.

- Dicks 1967, pp. 10–11.

- Dicks 1967, p. 12.

- Griffiths 1981, p. 298.

- Keen, Maurice (1973). England in the Later Middle Ages. London: Routledge. p. 438. ISBN 9780415027830.

- Hicks, M.A., The Wars of the Roses Yale 2002, p. 67

- Griffiths 1981, p. 677.

- Davis, Norman, ed. (1999). "Letter 14". The Paston Letters. Oxford University Press. pp. 26–29.

- Griffiths 1981, p. 628.

- Sevenoaks Preservation Society: The Rising in Kent in 1450 A.D., J.K.D. Copy in Sevenoaks public library.

- Encyclopedia of the Wars of the Roses, ed. John A. Wagner, (ABC-CLIO, 2001), 48.

- Sadler, John (2010). The Red Rose and the White: the Wars of the Roses 1453–1487. Longman. pp. 49–51.

- Griffiths 1981.

- Abram, William Alexander (1877). Parish of Blackburn, County of Lancaster: A History of Blackburn, Town and Parish. Blackburn: J. G. & J. Toulmin. p. 57.

- Jones, Dan (2014). The Hollow Crown: The Wars of the Roses and the Rise of the Tudors. Faber & Faber. p. 195. ISBN 9780571288090.

- Weir, Alison (2011). The Wars of the Roses. Random House. p. 333. ISBN 9780307806857.

- Wolffe 1981, pp. 342–344.

- McKenna, John W. (1965). "Henry VI of England and the Dual Monarchy: aspects of royal political propaganda, 1422–1432". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 28: 145–162. doi:10.2307/750667. JSTOR 750667.

- Wolffe, Bertram (1981). Henry VI. London: Eyre Methuen. p. 347.

- de Commynes, Philippe (2007). Blanchard, Joel (ed.). Mémoires. I. Geneva: Droz. p. 204.

- Johnson, Lauren (2019). Shadow King: The Life and Death of Henry Vi. United Kingdom: Head of Zeus. pp. 561–566. ISBN 9781784979645.

- "Plantagenet Of Lancaster – Henry VI". English Monarchs. 2004.

- "The Roos Monument in the Rutland Chantry Chapel". Archive for the ‘St George’s Chapel’. College of St. George. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- Duffy 1992, pp. 164–165.

- Duffy 1992, p. 165.

- Craig 2003, p. .

- Duffy 1992, p. 161.

- Duffy 1992, p. 185.

- Duffy 1992, p. 188.

- Duffy 1992, p. 169.

- Duffy 1992, p. 184.

- Duffy 1992, p. 195.

- Craig 2003, p. 189.

- Velde, Francois R. "Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family". Heraldica.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

Works cited

- Allmand, C. (30 April 1982), "The Coronations of Henry VI", History Today, vol. 32 no. 5, archived from the original on 28 July 2017

- "Henry VI, king of England". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 July 1999.

- Cheetham, A. (1 November 2000). Antonia Fraser (ed.). The Wars of the Roses. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22802-3.

- Craig, L. (2003). "Royalty, Virtue, and Adversity: The Cult of King Henry VI". Albion. 35 (2): 187–209. doi:10.1017/S0095139000069817. JSTOR 4054134.

- Dicks, S. (1967). "Henry VI and the Daughters of Armagnac: A Problem in Medieval Diplomacy" ( ). The Emporia State Research Studies. 15 (4: Medieval and Renaissance Studies): 5–12. OCLC 1567844.

- Duffy, E. (1992). The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400–1580. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06076-8.

- Griffiths, R.A. (1981). The Reign of King Henry VI. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04372-5.

- Griffiths, R.A. (28 May 2015). "Henry VI (1421–1471)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online) (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12953. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McKenna, J. (1965). "Henry VI of England and the Dual Monarchy: Aspects of Royal Political Propaganda, 1422–1432". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 28: 145–162. doi:10.2307/750667. JSTOR 750667.

- Tout, T. (1891). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 26. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Wolffe, B. (10 June 2001). Henry VI. Yale English Monarchs series. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08926-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry VI of England. |

Henry VI of England Cadet branch of the House of Plantagenet Born: 6 December 1421 Died: 21 May 1471 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Henry V |

King of England Lord of Ireland 1422–1461 |

Succeeded by Edward IV |

| Preceded by Edward IV |

King of England Lord of Ireland 1470–1471 | |

| Preceded by Charles VI |

— DISPUTED — King of France 1422–1453 Disputed by Charles VII Reason for dispute: Treaty of Troyes |

Succeeded by Charles VII as undisputed king |

| Peerage of England | ||

| Vacant Title last held by Henry of Monmouth |

Duke of Cornwall 1421–1422 |

Vacant Title next held by Edward of Westminster |

| French nobility | ||

| Preceded by Henry V |

Duke of Aquitaine 1422–1453 |

Annexed by France |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Preceded by Edward of York |

— TITULAR — King of England Lord of Ireland Lancastrian claimant 1461–1470 1471 Reason for succession failure: Overthrow by Yorkists |

Succeeded by Edward of York |

| Succeeded by Henry Tudor | ||

.jpg)