History of Devon

Devon is a county in south west England, bordering Cornwall to the west with Dorset and Somerset to the east. There is evidence of occupation in the county from Stone Age times onward. Its recorded history starts in the Roman period when it was a civitas. It was then a separate kingdom for a number of centuries until it was incorporated into early England. It has remained a largely agriculture based region ever since though tourism is now very important.

Prehistory

Devon was one of the first areas of Great Britain settled following the end of the last ice age. Kents Cavern in Torbay is one of the earliest places in England known to have been occupied by modern man. Dartmoor is thought to have been settled by Mesolithic hunter-gatherer peoples from about 6000 BC, and they later cleared much of the oak forest, which regenerated as moor. In the Neolithic era, from about 3500 BC, there is evidence of farming on the moor, and also building and the erection of monuments, using the large granite boulders that are ready to hand there; Dartmoor contains the remains of the oldest known buildings in England. There are over 500 known Neolithic sites on the moor, in the form of burial mounds, stone rows, stone circles and ancient settlements such as the one at Grimspound. Stone rows are a particularly striking feature, ranging in length from a few metres to over 3 km. Their ends are often marked by a cairn, a stone circle, or a standing stone (see menhir). Because most of Dartmoor was not ploughed during the historic period, the archaeological record is relatively easy to trace.

The name "Devon" derives from the tribe of Celtic people who inhabited the south-western peninsula of Britain at the time of the Roman invasion in 43 AD, the Dumnonii - possibly meaning 'Deep Valley Dwellers' (Cornish: Dewnans, Welsh: Dyfnaint, Breton: Devnent) or 'Worshippers of the god Dumnonos'. This tribal name carried on into the Roman and post-Roman periods. The Dumnonii did not mint coins, unlike their neighbours to the east the Durotriges, but coins of the Dobunni have been found in the area. Early trading ports are known to have existed at Mount Batten (Plymouth)[1] and at Bantham where ancient tin ingots were found in 1991-92 according with classical reports of tin trading with the Mediterranean [2]Aillen Fox, 1996.

Roman period

Devon was not as Romanised as Somerset and Dorset, with evidence of occupation limited mainly to the area around Exeter where the Roman walls can still be seen. It is likely a settlement at Exeter of some sort pre-existed the Romans and that the local Brythonic tribe inhabiting the area, the Dumnonii, maintained a tradition of independence. It appears that initially the Dumnonii tribe of Britons were a client kingdom of Rome, but from about AD 55 the Romans held at least part of the area under military occupation, maintaining a naval port at Topsham and a garrison of the 2nd Augustan Legion at Exeter, which they called 'Isca'. This banked and palisaded fortress contained mostly barracks and workshops, but also a magnificent bath-house and was occupied for approximately twenty years. Then the legion moved to Caerleon and the civilians of the surrounding settlement took control. All the associated trappings of local government followed, such as a forum and basilica and, eventually a stone city wall. The Roman administration stayed here for over three centuries. There were several smaller forts across the county and a number of pagan shrines, as remembered in the name of the Nymet villages (Nemeton), but the lands west of the Exe remained largely un-Romanized. The higher status locals there often lived in banked homesteads known as 'Rounds', while East Devon had a number of luxurious villas, such as that discovered at Holcombe, as well as Roman roads of the sophisticated cobbled type.

Post Roman Independence

After the end of Roman rule in Britain in about 410, the kingdom of Dumnonia emerged covering Devon, Cornwall and Somerset, based on the former Roman civitas and named after the pre-Roman Dumnonii. Gildas castigated King Constantine, who was probably a second generation ruler of Dumnonia in the early sixth century.[3] The Roman episcopal structure survived, and shortly before 705 Aldhelm, abbot of Malmesbury, wrote a letter to King Geraint of Dumnonia and his bishops.[4]

Exeter, known as “Caer Uisc”, may have been central to the kingdom but some historians and antiquaries have speculated that the Kings of Dumnonia may have been itinerant with no fixed capital and moved their court from place to place. The Welsh Triads name Celliwig in Cornwall as a possible site of a royal court, another is High Peak close to Sidmouth. The former Roman city of Exeter may have become an ecclesiastical centre, as evidenced by a sub-Roman cemetery discovered near the cathedral. The Brythonic cemetery in Exeter may have been attached to the monastery attended by the young Wilfred St. Boniface (said to be a native of Crediton) in the late 7th century. However its Abbot had a purely Saxon name, suggesting it was an Anglo-Saxon foundation.

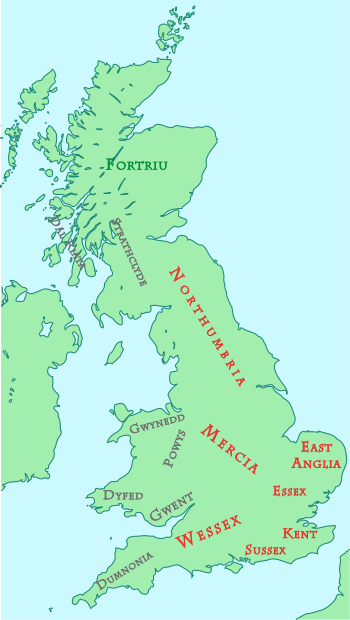

Anglo-Saxon conquest of Dumnonia

The date that the Anglo-Saxons began to settle in Devon is not certain. Raids westwards from the core territories of Wessex seem to have been set in motion about 660. After a battle fought probably at Penselwood in 658 the West Saxons advanced to the River Parrett and by 682 they had reached the Quantocks and were pressing forward into the coastal plain.[5] Wessex under King Cynewulf emerged from Mercian domination and began advancing west again from Taunton,[6] established as an advanced West Saxon position in 710 by King Ine, who defeated in that year the last recorded independent king in Devon; the codified Laws of Ine made provision for the Wealhas, the Welsh "foreigners", some of whom retained positions of responsibility.[7] The end of the fighting appears to have been a protracted and miserable affair. Campaigns by King Ecgberht of Wessex in Devon between 813 and 822 appear to have resulted in the defeat of the West Welsh in Cornwall but not their complete disposition. William of Malmesbury reports negotiations between King Alfred of Wessex and King Dungarth of the Cornish in c. 876 held somewhere near Exmoor in Devon; presumably Alfred would have sought reassurances over his western frontier as he conspired to defeat the Danes.[8] It seems most likely that the final acts of conquest of Devon by Wessex came under King Æthelstan of the English. William of Malmesbury claimed that "the Britons and Saxons inhabited Exeter aequo jure" - "as equals". However Æthelstan notably expelled “that filthy race” from Exeter in 927.[9] Some sources, notably the Cornish antiquary William Borlase, state that the expulsion of the Britons from Exeter was the first act in a military campaign against the West Welsh led by Æthelstan. William Borlase says there was a battle against King Howel of the West Welsh at Haldon near Teignmouth in 936 where the West Welsh were soundly defeated. It seems they were then pursued westwards across the River Tamar and through Cornwall where they were defeated again close to Land's End in what may have been a “last-ditch” encounter that probably ended in slaughter,[6] thus rendering the statement made centuries earlier and known to us as The Groan of the Britons seem morbidly appropriate; "The barbarians drive us to the sea, the sea drives us to the barbarians, between these two means of death we are either killed or drowned". An inflamed and astonished Welsh reaction to these events is found in the contemporary poem, Armes Prydein, where the last independent king of Cornwall, reputedly King Howel, was said to lament:

"Sorrow springs from a world upturned."[10]

The Britons (West Welsh, Cornishmen) certainly survived in Devon beyond this date because they apparently re-entered Exeter at a later date and an area was known as "Brittayne" in the south west quarter of the city until the 18th century. The Celtic language is reputed to have survived in parts of Devon until the Middle Ages, in particular the South Hams, according to Risdon and Carew.

Evidence for the Anglo-Saxon genetic influence on Devon has been found in UK wide genetic studies by the Wellcome Trust, University of Oxford & University College London. They discovered that Devon is markedly distinct from Cornwall, and that although Devon was also distinct from the rest of Southern England, it was less so than Cornwall. Oxford University researcher, Sir Walter Bodmer, said this could likely be explained by the Anglo-Saxons contributing less DNA to the gene pool in Cornwall than in Devon. The distinction of Devon from the larger cluster of Southern England, The Midlands and parts of the North of England, is explained by the fact these areas saw more domestic immigration during the Industrial Revolution than Devon did.[11]

Devon in Anglo Saxon times

By the 9th century, the major threat to peace in Devon came from Viking raiders. To confound them, Alfred the Great refortified Exeter as a defensive burh, followed by new erections at Lydford, Halwell and Pilton, although these fortifications were relatively small compared to burhs further east, suggesting these were protection for only the elite. Edward the Elder built similarly at Barnstaple and Totnes. The English defeated a combined Cornish and Danish force at Callington in 832. Sporadic Viking incursions continued, however, until the Norman Conquest, including the disastrous defeat of the Devonians at the Battle of Pinhoe in 1001. A few Norse placenames remain as a result, for example Lundy Island. The men of Devon are said by Asser to have fought the Danes at the battle of the Battle of Cynwit in 878, which may have been at Kenwith Castle or Countisbury, although Cannington in Somerset is also claimed as the site of the battle. In 894, the Danes attempted to besiege Exeter but were driven off by King Alfred but it was sacked in 1001.

Devon formed part of the bishopric of Sherborne (Dorset) after this was set up in 705 AD. In the early 10th century, King Athelstan refounded the monastery at Exeter. Roman Catholicism gradually took over from Celtic Christianity as minster churches were established across the county. Devon was given its own bishopric in 905, initially at Bishop's Tawton, though it quickly moved to Crediton. As part of the general move towards urban cathedrals in the late Saxon period, Bishop Leofric eventually transferred his see to the old abbey at Exeter in 1050. The boundary between Devon and Cornwall was fixed as the east bank of the River Tamar by King Athelstan of Wessex in 928.

Norman and medieval period

Immediately after the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror recognised the importance of securing the loyalty of the West Country and thus the need to secure Exeter. The city managed to withstand an eighteen-day siege[12] and the new king was only eventually allowed to enter upon honourable terms.

The many great estates subsequently held by William's barons in Devon were known as "honours". Chief amongst them were Plympton, Okehampton, Barnstaple, Totnes and Harberton. In the 12th century, the honour of Plympton, along with the Earldom of Devon, was given to the Redvers family. In the following century, it passed to the Courtenays, who had already acquired Okehampton, and, in 1335, they received the earldom too. It was also in the 14th century that the Dukedom of Exeter was bestowed on the Holland family, but they became extinct in the reign of Edward IV. The ancestors of Sir Walter Raleigh, who was born at East Budleigh, held considerable estates in the county from a similar period. Devon was given an independent sheriff. Originally an hereditary appointment, this was later held for a year only. In 1320, the locals complained that all the hundreds of Devon were under the control of the great lords who did not appoint sufficient bailiffs for their proper government.

During the civil war of King Stephen’s reign, the castles of Plympton and Exeter were held against the king by Baldwin de Redvers in 1140. Conflict resurfaced in the 14th and 15th centuries, when the French made frequent raids on the Devon coast and, during the Wars of the Roses, when frequent skirmishes took place between the Lancastrian Earl of Devon and Yorkist Lord Bonville. In 1470, Edward IV pursued Warwick and Clarence as far as Exeter after the Battle of Lose-coat Field. Warwick eventually escaped to France via Dartmouth. Later, Richard III travelled to Exeter to personally punish those who had inflamed the West against him. Several hundred were outlawed, including the Bishop and the Dean.

Dartmoor and Exmoor (mainly in Somerset) were Royal Forests, i.e. hunting preserves. The men of Devon paid 5000 marks to have these deforested in 1242. The 11th to 14th centuries were a period of economic and population growth, but the Black Death in 1348 and subsequent years caused decline in both with resulting social change; many villages and hamlets such as 12th century Hound Tor were said to have been deserted whilst new settlements were later granted to the rising class of tenant farmers exemplified by the surviving 14th century Dartmoor longhouse settlement at Higher Uppacott such that peasant farmers subsequently prospered with large flocks of sheep and cattle. Towns such as Totnes were particularly noted for their wealth owing to the wool and tin trade with the Continent in this period.

Tudor and Stuart period

Early in Henry VII's reign, the royal pretender, Perkin Warbeck, besieged Exeter in 1497. The King himself came down to judge the prisoners and to thank the citizens for their loyal resistance.

Great disturbances throughout the county followed the introduction of Edward VI's Book of Common Prayer. The day after Whit Sunday 1549, a priest at Sampford Courtenay was persuaded to read the old mass.[13] This insubordination spread swiftly into serious revolt. The Cornish quickly joined the men of Devon in the Prayer Book Rebellion and Exeter suffered a distressing siege until relieved by Lord Russell.[14]

Devon is particularly known for its Elizabethan mariners, such as Sir Francis Drake, Mayor of Plymouth, Gilbert, Sir Richard Grenville and Sir Walter Raleigh. Plymouth Hoe is famous as the location where Drake continued to play bowls after hearing that the Spanish Armada had been sighted. Plymouth was also the final departure point for the Mayflower in 1620, although the settlers themselves were mainly drawn from England.

During the Civil War, the cities of Devon largely favoured the Parliamentarian cause, and by and large the rural areas favoured the Royalists. but there was a great desire for peace in the region and, in 1643 a treaty for the cessation of hostilities in Devon and Cornwall was agreed. Only small-scale skirmishes continued until the capture of Dartmouth and Exeter in 1646 by Sir Thomas Fairfax. He then captured Tiverton and defeated Lord Hopeton's army at Torrington. The last place held for the king was Charles Fort at Salcombe.

After the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685, Judge Jefferies held one of his ‘bloody assizes’ at Exeter. In 1688, the Prince of Orange first landed in England at Brixham (where his statue stands in the town harbour) to launch the Glorious Revolution and his journey to London to claim the English throne as William III. He was entertained for several days at both Forde and at Exeter.

Modern period

In the modern period, after 1650, the City of Plymouth has had a large growth becoming the largest city in Devon, mainly due to the naval base at Devonport on its west. Plymouth played an important role as a naval port in both World War I and World War II. South Devon was a training and assembly area during World War II for the D-Day landings and there is a memorial to the many soldiers who were killed during a rehearsal off Slapton Sands. Both Plymouth and Exeter suffered badly from bombing during the war and the centre of Exeter and vast swathes of Plymouth had to be largely rebuilt during the 1960s.

Cold winters were a feature of the 17th century, that of 1676 being particularly hard. Smallpox epidemics occurred in the 1640s, 1710s and 1760s, resulting in many deaths. In October 1690 there was an earthquake in Barnstaple. Daniel Defoe published an account of a tour through Devon in 1724 and 1727. South Devon impressed him but be thought that north Devon was wild, barren and poor.

During the Napoleonic War a prison was built at Princetown on Dartmoor to hold French and American prisoners of war. This prison is still in use.

In 1842 the population was said to be mainly employed in agriculture. The population declined in the 19th century but has subsequently increased due to the favourable climate and the arrival of the railways.

In the 19th and 20th centuries. Devon has experienced great changes, including the rise of the tourist industry on the so-called English Riviera, decline of farming and fishing, urbanisation, and also proliferation of holiday homes in for example Salcombe. Devon has become famous for its clotted cream and cider. Dartmoor has become a National Park, as has Exmoor.

Devon has suffered many severe storms, including one that largely swept away Hallsands in 1917.

Politically Devon has had a tendency to lean towards the Conservative and Liberal/Liberal-Democrat parties.

Mining history

Devon has produced tin, copper and other metals from ancient times. Until about 1300 it produced more than Cornwall but production declined with the opening of the deep Cornish mines. Tin was found largely on Dartmoor's granite heights, and copper in the areas around it. It was exported from Mount Batten in prehistoric times. The Dartmoor tin-mining industry thrived for hundreds of years, continuing from pre-Roman times right through to the first half of the 20th century. In the eighteenth century Devon Great Consols mine (near Tavistock) was believed to be the largest copper mine in the world.

Devon's tin miners enjoyed a substantial degree of independence through Devon's stannary parliament, which dates back to the twelfth century. Stannary authority exceeded English law, and because this authority applied to part-time miners (e.g. tin streamers) as well as full-time miners the stannary parliament had significant power. Until the early 18th century the stannary parliament met in an open air parliament at Crockern Tor on Dartmoor with stannators appointed to it from each of the four stannary towns. The parliament maintained its own gaol at Lydford and had a brutal and 'bloody' reputation (indeed Lydford law became a byword for injustice), and once even gaoled an English MP in the reign of Henry VIII.

See also

References

- Barry Cunliffe : Mount Batten Plymouth: A Prehistoric and Roman Port. Oxford University Press 1988

- The Archaeology of Mining & Metallurgy in Southwest Britain

- Yorke, Barbara (2013). "Britain and Ireland c. 500". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c. 500–c. 1100. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- Pickles, Thomas (2013). "Church Organization and Pastoral Care". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c. 500–c. 1100. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- H. R. Loyn, Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 2nd ed. 1991:49f.

- Major, Albany (1913) Early Wars of Wessex, pp. 92-98. Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-2068-9.

- Loyn 1991.

- Major, Albany (1913) Early Wars of Wessex, pp. 97. Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-2068-9.

- Payton, Philip (1996) Cornwall. Fowey: Alexander Associates

- Wood, Michael (1981) In Search of the Dark Ages, p.135. BBC Books. ISBN 0-563-17835-3.

- "Who do you think you really are? The first fine-scale genetic map of the British Isles". wellcome.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Palliser, David Michael; Clark, Peter; and Daunton, Martin J. (2000). The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, p. 595. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41707-4.

- Heal, Felicity (2003). Reformation in Britain and Ireland, p. 225. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-826924-2.

- Secor, Philip Bruce (1999). Richard Hooker: Prophet of Anglicanism, p. 13. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-86012-289-1.

Further reading

- Samuel Tymms (1832). "Devonshire". Western Circuit. The Family Topographer: Being a Compendious Account of the ... Counties of England. 2. London: J.B. Nichols and Son. OCLC 2127940.