Treaty of Falaise

The Treaty of Falaise was a forced written agreement made in December 1174 between the captive William I, King of Scots, and Henry II, King of England.

During the Revolt of 1173-1174, William joined the rebels and was captured at the Battle of Alnwick during an invasion of Northumbria. He was transported to Falaise in Normandy while Henry prosecuted the war against his sons and their allies. Left with little choice, William agreed to the Treaty and therefore England’s dominion over Scotland. For the first time, the relationship between the king of Scots and the king of England was to be set down in writing.[1] The Treaty’s provisions affected the Scottish king, nobles, and clergy; their heirs; judicial proceedings, and transferred the castles of Roxburgh, Berwick, Jedburgh, Edinburgh, and Stirling over to English soldiers; in short, where previously the king of Scots was supreme, now England was the ultimate authority in Scotland.

During the next 15 years, William was forced to observe Henry's overlordship, such as needing to obtain permission from the English crown before putting down local uprisings.[2] The humiliation for William caused domestic trouble for him in Scotland, and Henry’s authority extended as far as picking William’s bride.

The treaty was annulled in 1189 when Richard I, Henry's successor, was distracted by his interest in joining the Third Crusade, and William's offer of 10,000 marks sterling. More pre-disposed to William than his father, Richard drew up a new charter on December 5, 1189, known as the Quitclaim of Canterbury, that nullified the Treaty of Falaise in its entirety.[3] This new written agreement restored Scottish sovereignty, reverting back to the previously vague and ill-defined personal traditions of fealty and homage between Scottish and English kings, rather than the direct subjugation that Henry demanded.

Background

The Northumbrian Question

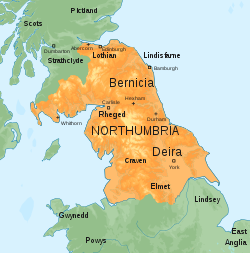

To understand how William came to be captured at Alnwick, one must go back to the question of Northumbria. The seeds of William’s discontent were sown in July 1157, when Henry II deprived his brother Malcolm IV, king of Scots, of certain lands and titles that their grandfather, David I, had secured for Scotland from Stephen, king of England, in 1139.[4] The ill-defined border of northern England and southern Scotland had been a matter of dispute depending on the relative power and relationship between Scottish and English kings in the 12th century. Taking advantage of English civil unrest during The Anarchy, the succession crisis between Stephen and Empress Matilda, Henry II’s mother, David invaded northern England on behalf of the Empress’ claim to the English throne.[3] While he had sworn allegiance to his niece Matilda as Henry I’s successor in 1127, this may have amounted to a principled pretext for his invasion as David believed that Northumbria and Cumberland were his by right through his late wife.[4] Through the second Treaty of Durham in 1139, he secured from Stephen Scottish control of these border lands, including the Earldom of Northumbria for his son, Henry, father of Malcolm and William.[4] For Scotland, Northumbria, Cumberland, and other border lands won by David were now viewed as hereditary, and no longer disputed. However, by retaining English control of two castles in Northumbria, Bamburgh and Newcastle, Stephen was able to keep the Northumbrian question on the table for future disputes.

A King, Spurned

William assumed the Scottish throne in 1164, and almost immediately set out to reclaim the Earldom of Northumbria, which he still viewed as his rightful inheritance. Perhaps taking a cue from his grandfather’s maneuvers, William attempted to capitalize on Henry’s divided attentions by pressing his claim for Northumbria and Cumberland in 1166. Joining Henry to quell unrest in Normandy, William participated in the military campaign, perhaps as a gesture of good faith, but ultimately returned to Scotland empty-handed.[4] A letter sent to Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, around this time describes Henry’s anger when one of his knights spoke favorably of William, depicting a deteriorating personal relationship between the two kings. Further evidence points to William sending emissaries to Louis VII in 1168 amidst renewed warfare between the English and French, but nothing came of this once peace negotiations began between Henry and Louis. A few years later, William tried again when meeting with Henry at Windsor in April 1170, but was rebuffed; however, as earl of Huntingdon (but not as king of Scots) he was required to perform homage to Young Henry, who was now crowned as king-designate.[4]

William Joins the Revolt

.png)

As three of Henry’s sons, Young Henry, Richard, and Geoffrey; his wife, Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, along with various nobles and barons; and aided by Louis VII of France; began their rebellion in 1173, William saw another opportunity to reclaim Northumbria. He received overtures from Young Henry, and a letter from Louis promising that William “should be put in possession of the land which his ancestors had once held…the land north of the Tyne or Northumberland, and the counties of Westmoreland and Cumberland.”[5] Unsure which side to join, he sent messengers to Henry in Normandy offering 1000 knights and 30000 soldiers, and in return “only what is his lawful due, that is to say, first of all Northumberland, to which no one has so good a right as himself.”[5] Rejected again by Henry, William aligns with the rebels and invades northern England.

While directing a scattered series of raids in Northumbria, on July 13, 1174, William left himself with only a small retinue of knights and was surprised by a force of Henry’s loyalists at Alnwick. Upon identifying the English advancing at close range, William mounted his horse and cried, ‘We shall now see who will act the part of a good knight!”[5] He cut his way through the enemy until his horse was killed out from under him, becoming trapped and forced to surrender to Ranulph de Glanvill. William was brought to Newcastle and then to Richmond, to await his fate from Henry. With the main threat on his northern front subdued, on July 26 Henry had William brought to him at Northampton “with his feet fastened beneath a horse’s belly,” an especially demeaning way to treat a fellow king.[6] For William, this ride of shame was only just the beginning.

Eventually brought to the castle in Falaise, William waited out the now-inevitable conclusion of the rebellion. An agreement was drawn up while William was in captivity in Falaise, but it was issued at Valognes on December 8, 1174.[7] As per the agreement, Henry arranged a public ceremony, held in York on August 10, 1175, where William sealed the document in front of his brother and heir, David, and a host of Scottish nobles, and the Treaty was read aloud for all to witness.[7]

The Treaty of Falaise, 1174

Text of the Treaty

This is the agreement and treaty which William, king of Scots, made with his lord king, Henry, the son of Maud, the empress:

William, king of Scots, has become liegeman of the lord king (Henry) against every man in respect of Scotland and in respect of all his other lands; and he has done fealty to him as his liege lord, as all the other men of the lord king (Henry) are wont to do. Likewise, he has done homage to Henry the king, son of King Henry, saving only the fealty which he owes to the lord king, his father.

And all the bishops and abbots and clergy of the king of Scots and their successors shall do fealty to the lord king (Henry) as to their liege lord, in the same way as the lord king’s other bishops are wont to do; and they shall likewise do fealty to Henry the king, his son, and to his heirs.

And the king of Scots, and David, his brother, and his barons and other men, have granted to the lord king (Henry) that the Scottish Church shall make submission to the English Church as it ought to do, and as it was wont to do in the time of the lord kin’s predecessors, kings of England. Likewise, Richard, bishop of St. Andrews, and Richard, bishop of Dunkeld, and Geoffrey, abbot of Dunfermline, and Herbert, prior of Coldingham, have granted that the English Church should have such rights in Scotland as it ought to have, and that they will themselves not oppose any of the rights of the English Church. And they have pledged themselves in respect of this admission by performing liege fealty to the lord king and Henry, his son.

Likewise the other Scottish bishops and clergy shall do so by a pact made between the lord king (Henry) and the king of Scots, and David, his brother, and his barons.

The earls also and barons and such other men holding land from the king of Scots as the lord king Henry may select, shall also do homage to the lord king as against all men, and shall swear fealty to him as their liege lord, in the same way as his other men are wont to do. And they shall do the same to Henry the king, his son, and to his heirs, saving only the fealty which they owe to the lord king, his father. Likewise, the heirs of the king of Scots, and of his barons, and of his men shall do liege homage to the heirs of the lord king (Henry) against all other men.

Further, the king of Scots and his men shall not receive, either in Scotland or in any of his other lands, any exile from the lands of the lord king who has been expelled therefrom by reason of felony, unless he wishes to justify himself in the court of the lord king (Henry), and to submit to the judgment of his court. Otherwise, the king of Scots and his men shall take such a one as quickly as they can and bring him to the lord king (Henry) or to his justiciars or to his bailiffs in England.

Again, if there comes to England any fugitive expelled as a felon from the lands of the king of Scots he shall not be received in the lands of the lord king (Henry) unless he wishes to justify himself in the court of the king of Scots, and to submit to the judgment of his court. Otherwise such a one shall be delivered to the men of the king of the Scots by the bailiffs of the lord king (Henry) wherever he is found.

Further, the men of the lord king (Henry) shall continue to hold the lands which they held, and which they ought to hold, from the lord king (Henry) and from the king of Scots and from their men. And the men of the king of Scots shall continue to hold the lands which they held, and which they ought to hold, from the lord king (Henry) and from his men.

In order that treaty and pact with the lord king (Henry) and Henry the king, his son, and their heirs, may be faithfully kept by the king of Scots and his heirs, the king of Scots has delivered to the lord king (Henry) the castle of Roxburgh, and the castle of Berwick, and the castle of Jedburgh, and the castle of Edinburgh, and the castle of Stirling to be held by the lord king (Henry) at his pleasure. And the king of Scots shall pay for the garrison of these castles out of his own revenue at the pleasure of the lord king (Henry).

Further, in pledge of the aforesaid treaty and pact, the king of Scots has delivered to the lord king (Henry) his brother, David, as a hostage, and also the following: Earl Duncan, Earl Waldewin, Earl Gilbert, the earl of Angus, Richard of Morville the constable, Niz son of William, Richard Comyn, Walter Corbet, Walter Olyfard, John de Vals, William of Lindsay, Philip de Coleville, Philip of Valognes, Robert Frembert, Robert de Burneville, Hugh Giffard, Hugh Rydal, Walter Berkele, William de la Haye, William de Mortemer.

When the castles have been handed over, then shall William king of Scots, and David his brother, be released. And (again after the castles have been handed over) the earls and barons aforesaid shall be released, but only after each one has delivered his own hostage, to wit, his legitimate son if he has one, or otherwise his nephew or nearest heir.

Further, the king of Scots and his barons aforesaid have guaranteed that with good faith and without evil intent and without excuse, they will see to it that the bishops and barons, and other men of their land, who were not present when the king of Scots made his pact with the lord king (Henry) and with Henry the king, his son, shall do the same liege homage and fealty as they themselves have done. And the barons and men, who were not present at this agreement, shall give such hostages as the lord king (Henry) shall determine.

Further, the bishops, earls and barons aforesaid have covenanted with the lord king (Henry) and with Henry the king, his son, that is the king of Scots shall by any mischance default in his fealty to the lord king (Henry) and his son, and shall thus break the aforesaid agreement, then they, the aforesaid bishops, earls and barons will hold to the lord king (Henry), as to their liege lord, against the king of Scots and against all men hostile to the lord king (Henry). And the bishops shall place the land of the king of Scots under interdict until the king of Scots returns to the lord king (Henry) in his fealty.

The king of Scots and David, his son, and all the aforesaid barons, as liegemen of the lord king (Henry) and of Henry the king, his son (saving only their fealty to the lord king, his father), have give full sworn assurance that the aforesaid treaty shall be strictly observed by them in good faith and without any evil intent.

And these are the witnesses: Richard, bishop of Avranches; John, dean of Salisbury; Robert, abbot of Malmesbury; Ralph, abbot of Montebourg; Herbert, archdeacon of Northampton; Walter of Coutances; Roger, the king’s chaplain; Osbert, clerk of the chamber; Richard, son of the lord king, and count of Poitou; Geoffrey, son of the lord king, and count of Brittany; William, earl of Essex; Hugh, earl of Chester; Ricard of Le Hommet, the constable; the count of Meulan; Jordan Tesson; Humphrey “de Bohun”; William of Courcy, the seneschal; William, son of Aldhelm, the seneschal; Alfred of Saint-Martin, the seneschal; Gilbert Malet, the seneschal.

At Falaise.[8]

Analysis of the Treaty's Provisions

The Treaty set terms that, for the first time written down in an official document and declared publicly, defined the king of Scots to be subservient to the king of England.[7] Its provisions affected the Scottish king, nobles, and clergy, and all their heirs; judicial proceedings, and the loss of castles; in short, where previously the king of Scots was supreme, now England was the ultimate authority in Scotland.

The first proviso states clearly, “William, king of Scots, has become liegeman of the lord king (Henry) against every man in respect of Scotland and in respect of all his other lands; and he has done fealty to him as his liege lord, as all the other men of the lord king (Henry) are wont to do.” The Scottish king now explicitly owes fealty to England for Scotland, a remarkable change from the previous personal fealty traditions that existed before. When William paid homage to Henry previously, he did so as Earl of Huntingdon, not as king of Scots, and likewise for Malcolm and David and previous kings paying homage for their English holdings.[4] The dance of fealty among Scottish and English kings had historically been purposely vague, for diplomatic and personal reasons. Past Scottish kings had certainly been called ‘the man’ of English rulers, but this relationship was ill-defined and ambiguous.[9] Now, Henry was making English dominance clear in no uncertain terms, which extended beyond William.

Scottish nobles, like their king, now owed fealty to Henry and his heirs “against all men,” as did bishops, abbots, and clergy. This meant that the loyalty of Scottish nobles was greater towards Henry than William, and should he “draw back” from the agreement they must intervene on Henry’s behalf, an unprecedented direct intervention between the Scottish king and his people.[7] In addition to the clergy owing fealty, the Church of Scotland was now subject to the Church of England, an aggressive move to enshrine the Archbishop of York’s supremacy over Scotland, and one in which the king of England lacked authority to mandate.[4]

As further punishment, five castles – Roxburgh, Berwick, Jedburgh, Edinburgh, and Stirling - were also handed over to Henry, to be manned by English soldiers at Scotland’s expense. Another provision details the respective responsibilities for dealing with fugitives, with England able to try Scottish fugitives, but the Scots required to hand over English felons. To further secure the subservience of Scotland writ large, barons and bishops not present would be required to perform the same liege homage, and hostages comprising their heirs or nearest kin turned over.

Negotiated while William was prisoner, or rather dictated to him, the public act of submission occurred at the church of St. Peter’s in York in front of the chief men of the English kingdom. In front of his own nobles, clergy, knights, and freeholders, William and his brother sealed the document and had to suffer the additional embarrassment of it being read aloud to all.[10] Two crucial drafting details stand out that add to the scale of humiliation:

“Scotland was recurrently referred to as a land (terra), not as a kingdom (regnum) thereby anticipating by over a century Edward I’s vocabulary of demotion, while the premier-league status of Henry II’s title as ‘the lord king’ (dominus rex) stood in pointed superiority to that of William, merely ‘king of the Scots’ (rex Scottorum).”[10]

This concept of an English ‘overlordship’ or ‘high kingship’ would define this relationship throughout the duration of the Treaty. This was not explicitly a feudal relationship, as the Treaty did not call Scotland a ‘fief,’ nor that Scotland was ‘held’ or ‘had’ by the king of England.[4] Henry was the high king, allowing William to reign as king of Scots so long as he “acknowledged [his] ultimate dependence” on Henry’s overriding lordship.[10]

Aftermath

Following the enactment of this Treaty, William suffers several humiliations back in Scotland as a result of his weakened position. In Galloway, previous tensions surfaced to take advantage of William’s subjugation, and for which William needed to seek advice and council of Henry before commencing any actions to re-assert Scottish control over Galloway.[4] In Moray and Ross, brooding anger among certain nobles gave rise to potential challengers to the kingship, principally Donald MacWilliam, a possibly illegitimate descendant of Duncan II.[4] William’s frequent visits to Henry’s court, about eight in 10 years, his weakened position at home, and the embarrassment of having Scotland’s heirs held by Henry, gave rise to serious discontent.[10]

As William’s overlord, Henry was also afforded the right to pick his bride. William’s first request of Henry’s eldest granddaughter, Matilda of Saxony, was declined on a papal ruling of consanguinity, which may have been the outcome Henry sought.[4] In 1186, Henry selected Ermengarde, his kinswoman but the daughter of a relatively minor noble Richard, viscount of Beaumont, and for his gift he returned to William the castle at Edinburgh.[6] Taken with William’s reinstatement as the Earl of Huntingdon (which he passed immediately to David in 1185), William’s continued fealty, combined with Henry’s recognition of the more important French threats to his kingdom, provided the Scots with some positive gains a decade into the Treaty.[4]

For Henry, the Treaty was just another feather in his cap after quashing the rebellion; for he had already brought his rebellious children back in the fold, and neutralized Queen Eleanor by sentencing her to confinement under guard at various castles, a punishment he maintained for the rest of his life.[11] Despite his now direct overlordship of Scotland, Henry did not have to do much, nor was he asked very often, to intervene in general Scottish affairs. The only surviving evidence that a Scot appealed directly to Henry for assistance was from Abbot Archibald of Dunfermline. The abbot sought Henry's protection because of continued harassment at the port of Musselburgh from the English garrison stationed at nearby Edinburgh, not in response to an action William had taken as king of Scots.[1] A happenstance of timing during the rebellion played to his good fortune, as he performed public penance at Thomas Becket’s tomb on his return to England on July 12, 1174.[4] With William’s capture occurring the following day, Henry was at once able to move past the ugliness associated with Becket’s murder and claim divine intervention on his, and England’s, behalf against the Scots, the French, and his own children.

Revocation

Subjugation Ended

Upon Henry’s death in 1189, Richard I assumed the throne and received William shortly after his coronation. Distracted by his interest in departing for the Third Crusade, and much more pre-disposed to William than his father, on December 5, 1189, Richard drew up a new charter with William, known as the Quitclaim of Canterbury, that nullified the Treaty of Falaise in its entirety:

“Accordingly, William, king of the Scots, came to the king of England at Canterbury in the month of December, and did homage to him for his dignities in England, in the same manner that his brother Malcolm had held them. Richard, king of England, also restored to him the castle at Roxburgh, and the castle of Berwick, freely and quietly to be held by him; and he acquitted and released him and all his heirs from all homage and allegiance, for the kingdom of Scotland, to him and the kings of England, for ever. For this gift of his castles and for quitting claim to all fealty and allegiance for the kingdom of Scotland, and for the charter of Richard, king of England, signifying the same, William, king of Scots, gave to Richard, king of England, ten thousand marks sterling.”[6]

William, and Scotland, were now freed from their humiliating subjugation. The original Treaty of Falaise was handed over to William, and presumably destroyed.[12] A contemporary account of Scotland’s regained independence declared that “by God’s assistance, he [William] worthily and honourably removed his [Henry’s] heavy yoke of domination and servitude from the kingdom of the Scots.”[7]

Quitclaim of Canterbury, 1189

The Charter of the king of England as to the liberties granted by him to William, king of Scotland:

Richard, by the grace of God, king of England, duke of Normandy and Aquitane and earl of Anjou, to the archbishops, bishops, abbats, earls, barons, justices, and sheriffs, and all his servants and faithful people throughout the whole of England, greeting. Know ye that we have restored to our most dearly-beloved cousin William, by the same grace of king of the Scots, his castles of Roxburgh and Berwick, to be held by him and his heirs for ever as his own of hereditary right. We have also acquitted and released him of and from all covenants and agreements which Henry, king of England, our father, of happy memory, extorted from him by new charters, and in consequence of his capture; upon condition, however, that he shall in all things do unto us as fully as Malcolm, king of the Scots, his brother, did as of right unto our predecessors, and of right was bound to do. We likewise will do for him whatever rights our predecessors did and were bound to do for the said Malcolm, both in his coming with a safe-conduct to our court, and in his returning from our court, and while he is staying at our court, and in making due provision for him, and according to him all liberties, dignities, and honors due to him as of right, according as the same shall be ascertained by four of our nobles who shall be selected by us. And if any one of our subjects shall, since the time when the said king William was taken prisoner by our father, have seized upon any of the borders or marches of the kingdom of Scotland, without the same being legally adjudicated to him; then we do will that the same shall be restored to him in full, and shall be placed in the same state in which they were before he was so taken prisoner. Moreover, as to his lands which he may hold in England, whether in demesne or whether in fee, that is to say in the county of Huntingdon, and in all other counties, he and his heirs shall hold the said counties as fully and freely for ever as the said Malcolm held or ought to have held the same, unless the said Malcolm or his heirs shall have since enfeoffed any one of the same; on the further condition also that if any one shall be hereafter enfeoffed of the same, the services of said fees shall belong to him or his heirs. And if our said father shall have given anything to William, king of the Scots, we do will that the same shall be hereby ratified and confirmed. We have also restored to him all allegiances of his subjects and all charters which the king our father obtained of him by reason of his capture. And if any other charters shall chance, through forgetfulness, to have been retained by us or shall hereafter be found we do hereby order that the same shall be utterly void and of no effect. He has also become our liegeman as to all the lands for which his predecessors were liegemen to our predecessors, and has sworn fealty to ourselves and to our heirs. The following being witnesses hereto: - Baldwin, archbishop of Canterbury, Walter, archbishop of Rouen; Hugh, bishop if Durham; John, bishop of Norwich; Hubert, bishop of Salisbury; Hugh, bishop of Lincoln; Godfrey, bishop of Winchester; Gilbert, bishop of Rochester; Reginald, bishop of Bath; Hugh, bishop of Coventry; William, bishop of Worcester; Eleanor, the king’s mother; John, earl of Mortaigne, the king’s brother, and many others.[6]

Legacy

.png)

Even though the Treaty of Falaise was in effect for only fifteen years, it had a lasting impact on English-Scottish relations. The nature of the Treaty required that another written document would have to succeed it, as the Quitclaim of Canterbury did. The explosion of charters and treaties in the 12th and 13th centuries highlighted this growing method of diplomacy within the English isles, although their effect depended on who would enforce them. The immediate consequence was a reversion to the previous tradition of fealty and homage on a personal level, not “for” Scotland as Henry had demanded. The intrusive English “overlordship” was no more, but despite William’s umbrage at being the lesser, Henry did not truly exploit the Treaty’s powers, as evidenced by his decision to not even establish English garrisons in all the castles that William was required to surrender.[7] Henry’s ultimate goal may have been to keep the Scots in line, rather than him having to manage another kingdom.

Perhaps the most consequential legacy of Henry’s victory over the rebellion, which gave rise to this Treaty, stemmed from his visit to Becket’s tomb. Helping to cement for eternity a new patron saint of England, Henry pressed for total subjugation of Scotland as well. Regarding its provisos relating to the Church of England’s dominion over its Scottish counterpart, the Treaty of Falaise ultimately forced the opposite result. The question of England’s supremacy over the Church of Scotland had seemed to be answered by the Treaty. Henry tried to force the subjection of Scottish bishops per the Treaty at a council in Northampton, but a dispute between the archbishops of Canterbury and York over which of them should be Scotland’s metropolitan allowed time for an appeal to Rome. Pope Alexander III issued the bull Super anxietatibus on July 30, 1176, which declared that the bishops of Scotland should regard the pope as their metropolitan until further notice.[7] This became official in 1192 with the Cum universi establishing the Church of Scotland as an independent body.

When it comes to Northumbria, William was never able to get over the loss of his earldom. In 1194, he offered 15,000 marks of silver for Northumberland, but Richard would only part with the land and not the castles, which was unacceptable to William.[6] With John’s ascension in 1199, William made several more attempts over the years, each of which was rebuffed.[4] William dies in 1214, having never recovered Northumbria, the issue which defined so many of his actions relating to England throughout his long reign.[13]

In sum, the Treaty of Falaise played an important role in English and Scottish history, as its short-lived declaration of English dominion would set the table for more hostilities down the line. Future English kings would press these claims, and look to the Treaty’s spirit to force English dominion in Scotland, as well as Wales and Ireland. The revocation of the Treaty provided for a century of uneasy alliance, until Edward I capitalized on a succession crisis to re-assert England’s complete control over Scotland, leading to the Scottish Wars of Independence beginning in 1296.

References.

- Brown, Dauvit (2014). "Scottish Independence: Roots of the Thistle". History Today. 64.

- Lang, Andrew. (2012). The History Of Scotland - Volume 1: From The Roman Occupation To Feudal Scotland. Altenmünster: Jazzybee Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8496-0461-5. OCLC 863904059.

- Carpenter, David (David A.). The struggle for mastery : Britain 1066-1284. London. ISBN 978-0-14-193514-0. OCLC 933846754.

- Oram, Richard. (2011). Domination and Lordship : Scotland, 1070-1230. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2847-6. OCLC 714569833.

- Fantosme, Jordan (1840). Chronicle of the War Between the English and the Scots in 1173 and 1174. J.B. Nichols and Son.

- de Hoveden, Roger (1853). The Annals of Roger de Hoveden: Comprising the History of England and of Other Countries of Europe from A.D. 732 to A.D. 1201. H.G. Bohn.

- Broun, Dauvit. (2007). Scottish independence and the idea of Britain : from the Picts to Alexander III. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3011-0. OCLC 227208036.

- English historical documents. Douglas, David C. (David Charles), 1898-1982,, Whitelock, Dorothy,, Greenaway, George William,, Myers, A. R. (Alec Reginald), 1912-1980,, Rothwell, Harry,, Williams, C. H. (Charles Harold), 1895-. London. ISBN 0-415-14361-6. OCLC 34796324.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Barrow, G. W. S.,. Kingship and unity : Scotland 1000-1306 (Second edition, Edinburgh classic editions ed.). Edinburgh. ISBN 978-1-4744-0181-4. OCLC 908417467.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Davies, R. R. (2000). The first English empire : power and identities in the British Isles 1093-1343. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-154326-5. OCLC 70658106.

- Bailey, Katherine (May 2005). "Eleanor of Aquitaine". British Heritage. 26: 28–34.

- Broun, Dauvit (2001). "The church and the origins of Scottish independence in the twelfth century". Records of the Scottish Church History Society. 31: 1–34.

- Barrow, G. W. S. (1971). The acts of William I, King of Scots, 1165-1214. Edinburgh,: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-6421-5. OCLC 1085905103.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)