History of Birmingham

Birmingham has seen 1400 years of growth, during which time it has evolved from a small 7th century Anglo Saxon hamlet on the edge of the Forest of Arden at the fringe of early Mercia to become a major city. A combination of immigration, innovation and civic pride helped to bring about major social and economic reforms and to create the Industrial Revolution, inspiring the growth of similar cities across the world.

The last 200 years have seen Birmingham rise from market town into the fastest-growing city of the 19th century, spurred on by a combination of civic investment, scientific achievement, commercial innovation and by a steady influx of migrant workers into its suburbs. By the 20th century Birmingham had become the metropolitan hub of the United Kingdom's manufacturing and automotive industries, having earned itself a reputation first as a city of canals, then of cars, and most recently as a major European convention and shopping destination.

By the beginning of the 21st century, Birmingham lay at the heart of a major post-industrial metropolis surrounded by significant educational, manufacturing, shopping, sporting and conferencing facilities.

Prehistory

Stone Age

The oldest human artefact found within Birmingham is the Saltley Handaxe: a 500,000-year-old brown quartzite hand axe about 100 millimetres (3.9 in) long, discovered in the gravels of the River Rea at Saltley in 1892. Other parts or Birmingham are quite similar in this way, as people seem to have lived there for millennia .[1] This provided the first evidence of lower paleolithic human habitation of the English Midlands,[2] an area previously thought to have been sterile and uninhabitable before the end of the last glacial period.[3] Similarly aged axes have since also been found in Erdington and Edgbaston, and bioarchaeological evidence from boreholes in Quinton, Nechells and Washwood Heath suggests that the climate and vegetation of Birmingham during this interglacial period were very similar to those of today.[4]

The area became uninhabitable with the advancing glaciation of the last ice age, and the next evidence of human habitation within Birmingham dates from the mesolithic period. A 10,400-year-old settlement – the oldest within the city – was excavated in the Digbeth area in 2009, with evidence that hunter-gatherers with basic flint tools had cleared an area of forest by burning.[5] Flint tools from the later mesolithic period – between 8000 and 6000 years ago – have been found near streams in the city, though these probably represent little more than hunting parties or overnight camps.[6]

The oldest man-made structures in the city date from the Neolithic era, including a possible cursus identified by aerial photography near Mere Green, and the surviving barrow at Kingstanding.[7] Neolithic axes found across Birmingham include examples made of stone from Cumbria, Leicestershire, North Wales and Cornwall, suggesting the area had extensive trading links at the time.[6]

Bronze and Iron Ages

Stone axes used by the area's first farmers over 5,000 years ago have been found within the city and the first bronze axes date from around 4,000 years ago.[8] Pottery dating back to 2700BC has been found in Bournville.[9]

The most common prehistoric sites in Birmingham are burnt mounds – a form characteristic of upland areas and possibly formed by the heating of stones for cooking or steam bathing purposes. Forty to fifty have been found in the Birmingham area, all but one datable to the period 1700–1000 BC. Burnt mound sites such as that discovered in Bournville also show evidence of wider settlements, with clearances in the woodland and grazing animals.[10] Possible Bronze Age settlements with later Iron Age farmsteads have been discovered at Langley Mill Farm in Sutton Coldfield.[10] Further evidence of Iron Age settlement has been found at Berry Mound, a hill fort located in the Bromsgrove district of Worcestershire, near Shirley.[11]

Romano-British era, c. 47–c. 600

In Roman times a large military fort and marching camp, Metchley Fort, existed on the site of the present Queen Elizabeth Hospital near what is now Edgbaston in southern Birmingham. The fort was constructed soon after the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43. In AD 70, the fort was abandoned only to be reoccupied a few years later before being abandoned again in AD 120. Remains have also been found of a civilian settlement, or vicus, alongside the Roman fort.[12] Excavations at Parson's Hill in Kings Norton and at Mere Green have revealed a Roman kiln site.[13]

Although no archeological evidence has been found, the presence of the Old English prefix wīc- in Witton (wīc-tūn) suggests that it may have been the site of a significant Romano-British vicus or settlement, which would have been adjacent to the crossing of the River Tame by Icknield Street at Perry Barr.[14]

Roman military roads have been identified converging on the Birmingham area from Letocetum (Wall, near Lichfield) in the north; from Salinae (Droitwich) in the south east; from Alauna (Alcester) in the south,[15] and from Pennocrucium (Penkridge) in the north west.[16] In many places the courses of these roads – including the points where they met – have been lost as they pass through the urban area, though a section of the route from Wall is well preserved as it passes through Sutton Park.[17] Roads are also likely to have led via the known Roman settlements at Castle Bromwich and Grimstock Hill near Coleshill to Manduessedum (Mancetter), and to the fort at Greensforge near Kinver.[15] The existence of straight road alignments coinciding with early parish boundaries suggests another Roman road may have passed through Birmingham from east to west through Ladywood, Highgate and Sparkbrook, along the line of Ladywood Road, Belgrave Road and parts of Warwick Road.[18] The Roman routes from Wall and Alcester were together named Icknield Street during the later Medieval period, though the implication that they were viewed as a single route by the Romans may be misleading, and it is possible that the road from Droitwich was originally the more important of the two southern routes.[15]

Anglo-Saxon and Norman Birmingham, c. 600–1166

Foundation

Archaeological evidence from the Anglo Saxon era in Birmingham is slight[19] and documentary records of the era are limited to seven Anglo-Saxon charters detailing the outlying areas of King's Norton, Yardley, Duddeston and Rednal.[20] Place name evidence, however, suggests that it was during this period that many of the settlements that were later to make up the city, including Birmingham itself, were established.[21]

The name "Birmingham" comes from the Old English Beormingahām,[22] meaning the home or settlement of the Beormingas – a tribe or clan whose name literally means "Beorma's people" and which may have formed an early unit of Anglo-Saxon administration.[23] Beorma, after whom the tribe was named, could have been its leader at the time of the Anglo-Saxon settlement, a shared ancestor, or a mythical tribal figurehead. Place names ending in -ingahām are characteristic of primary settlements established during the early phases of Anglo-Saxon colonisation of an area, suggesting that Birmingham was probably in existence by the early 7th century at the latest.[24] Surrounding settlements with names ending in -tūn (farm), -lēah (woodland clearing), -worð (enclosure) and -field (open ground) are likely to be secondary settlements created by the later expansion of the Anglo-Saxon population,[25] in some cases possibly on earlier British sites.[26]

Anglo-Saxon settlement

The site of Anglo-Saxon and Domesday Birmingham is not known. The traditional view – that it was a village based around the crossing of the River Rea at Deritend, with a village green on the site that became the Bull Ring – has now largely been discredited,[27] and not a single piece of Anglo-Saxon material was found during the extensive archeological excavations that preceded the redevelopment of the Bull Ring in 2000.[28] Other locations have been suggested including the Broad Street area; Hockley in the Jewellery Quarter;[29] or the site of the Priory of St Thomas of Canterbury, now occupied by Old Square.[30] Alternatively early Birmingham may have been an area of scattered farmsteads with no central nucleated village,[29] or the name may originally have referred to the wider area of the Beormingas' tribal homeland, much larger than the later manor and parish and including many surrounding settlements.[14] Analysis of the pre-Norman linkages between parishes suggests that such an area could have extended from West Bromwich to Castle Bromwich, and from the southern boundaries of Northfield and King's Norton to the northern boundaries of Sutton Coldfield.[31]

During the early Anglo-Saxon period the area of the modern city lay across a frontier separating two peoples.[32] Birmingham itself and the parishes in the centre and north of the area were probably colonised by the Tomsaete or "Tame-dwellers", who were Anglian tribes who migrated along the valleys of the Trent and the Tame from the Humber Estuary and later formed the kingdom of Mercia.[33] Parishes in the south of the current city such as Northfield and King's Norton were colonised during a later period by the Hwicce, a Saxon tribe whose migration north through the valleys of the Severn and Avon followed the West Saxons' victory over the Britons at the Battle of Dyrham in 577.[34] The exact boundary between the two groups may not have been precisely defined, but is likely to be indicated by the boundaries of the later dioceses of Lichfield and Worcester established after the 7th century conversion of Mercia to Christianity.[32]

The late 7th century saw the kingdom of Mercia expand, absorbing the Hwicce by the late 8th century and eventually coming to dominate most of England, but the growth of Viking power in the later 9th century saw eastern Mercia fall to the Danelaw, while the western part, including the Birmingham area, came to be dominated by Wessex. During the 10th century Edward the Elder of Wessex reorganised western Mercia for defensive purposes into shires based around the fortified burhs established by his sister Æthelflæd. The Birmingham area again found itself a border region, with the parish of Birmingham forming part of the Coleshill Hundred of newly created Warwickshire, but other areas of the modern city falling within Staffordshire and Worcestershire.[35]

The Domesday manor

The first surviving documentary record of Birmingham is in the Domesday Book of 1086, where it is recorded as the small manor of Bermingeham, worth 20 shillings.

From William, Richard holds four hides in Birmingham. There is land for six ploughs, in the demesne, one. There are five villagers and four smallholders with two ploughs. The woodland is half a league long and two furlongs wide. The value was and is twenty shillings. Wulfwin held it freely in the time of King Edward.[36]

At the time of the Domesday survey, Birmingham was far smaller than other villages in the area, most notably Aston. Other local manors recorded in the Domesday survey were Sutton, Erdington, Edgbaston, Selly, Northfield, Tessall and Rednal. A settlement called "Machitone" is also mentioned in the survey: this was to later become Sheldon.[37]

The manor-house of Birmingham was located at the foot of the eastern side of the Keuper Sandstone ridge. Originally a small house, it was later developed into a timber-framed house surrounded by a moat fed by the River Rea.[37]

The medieval market town, 1166–1485

Establishment and expansion

The transformation of Birmingham from the purely rural manor recorded in Domesday Book started decisively in 1166, with the purchase by the lord of the manor, Peter de Birmingham, of a royal charter from Henry II permitting him to hold a weekly market "at his castle at Birmingham", and to charge tolls on the market's traffic. This was one of the earliest of the two thousand such charters that would be granted in England in the two centuries up to 1350,[38] and may have recognised a market that was already taking place, as lawsuits of 1285 and 1308 both upheld the claim that the Birmingham market had been held without interruption since before the Norman conquest.[39] Its significance remains, however, as Peter followed the investment with the deliberate creation of a planned market town[40] within his demesne, or manorial estate.[41]

This era saw the laying out of the triangular marketplace that became the Bull Ring;[42] the selling of burgage plots on the surrounding frontages granting privileges in the market and freedom from tolls;[43] the diversion of local trade routes towards the new site and its associated crossing of the River Rea at Deritend;[44] the rebuilding of the Birmingham Manor House in stone[45] and probably the first establishment of the parish church of St Martin in the Bull Ring.[46] By the time Peter's son William de Birmingham sought confirmation of the market's status from Richard I twenty three years later, its location was no longer "his castle at Birmingham", but "the town of Birmingham".[47]

The following period saw the new town expand rapidly in highly favourable economic circumstances.[48] The Birmingham market was the earliest to be established on the Birmingham Plateau – an area which accounted for most of the doubling or tripling of the population of Warwickshire between 1086 and 1348 as population growth nationally encouraged the settlement and cultivation of previously marginal land.[49] Surviving documents record the widespread enclosure of wasteland and clearance of woodland in King's Norton, Yardley, Perry Barr and Erdington during the 13th century, a period over which the cultivated area of the manor of Bordesley also increased twofold.[50] Demand for agricultural trade was further fuelled by the increasing requirement for rents to be paid in cash rather than labour, leading tenant farmers to sell more of their produce.[51] It would be almost a century before markets at Solihull, Halesowen and Sutton Coldfield provided the Birmingham market with any local competition,[52] and by then the success of Birmingham itself provided the model, with tenure at Solihull explicitly being granted "according to the liberties and customs merchant of the market of Birmingham".[43] Within a century of the 1166 charter Birmingham had grown into a prosperous town of craftsmen and merchants.[53] The signing of Letters patent indicate visits by the King to Birmingham in 1189, 1235 and 1237,[49] and two burgesses were summoned to represent the town in Parliament in 1275. This event was not repeated until the 19th century, but established Birmingham as a town of comparable significance to older Warwickshire towns such as Alcester, Coleshill, Stratford-upon-Avon and Tamworth.[54] Fifty years later the lay subsidy rolls of 1327 and 1332 show Birmingham to have overtaken all of these towns to become the third largest in the county, behind only Warwick itself and Coventry – at the time the fourth largest urban centre in England.[55]

Markets and merchants

Birmingham's market is likely to have remained primarily one for agricultural produce throughout the medieval period.[56] The land of the Birmingham Plateau, particularly the unenclosed area of the manor of Birmingham to the west of the town, was more suited to pastoral then arable agriculture[57] and excavated animal bones indicate that cattle were the dominant livestock, with some sheep but very few pigs.[58] References in 1285 and 1306 to stolen cattle being sold in the town suggest that the size of the trade at this time was sufficient for such sales to go unnoticed.[57] Trade through Birmingham diversified as a merchant class arose, however: mercers and purveyors are mentioned in early 13th century deeds,[56] and a legal dispute involving traders from Wednesbury in 1403 reveals that they were dealing in iron, linen, wool, brass and steel as well as cattle in the town.[56][59]

By the 14th century Birmingham seems to have been established as a particular centre of the wool trade. Two Birmingham merchants represented Warwickshire at the council held in York in 1322 to discuss the standardisation of wool staples, and others attended the Westminster wool merchants assemblies of 1340, 1342 and 1343, a period when at least one Birmingham merchant was trading considerable amounts of wool with continental Europe.[56] Aulnage records for 1397 give some indication of the size of Birmingham's textile trade at the time, the 44 broadcloths sold being a tiny fraction of the 3,000 sold in the major textile centre of Coventry, but making up almost a third of the trade of the rest of Warwickshire.[60]

Birmingham was also situated on several significant overland trade routes. By the end of the 13th century the town was an important transit point for the trade in cattle along drovers' roads from Wales to Coventry and the South East of England.[61] Exchequer accounts for 1340 record wine imported through Bristol being unloaded at Worcester and transported by cart to Birmingham and Lichfield.[62] This route from Droitwich is shown on the Gough Map of the mid-14th century and described by the contemporary Ranulf Higdon as forming part of one of the "Four Great Royal Roads" of England, running from Worcester to the River Tyne.[63]

The de Birmingham family were active in promoting the market, whose tolls would have formed an important part of the income from the manor of Birmingham, by then the most valuable of their estates.[64] The establishment of a rival market at Deritend in the neighbouring parish of Aston had led them to acquire the hamlet by 1270,[65] and the family is recorded enforcing the payment of tolls by traders from King's Norton, Bromsgrove, Wednesbury, and Tipton in 1263, 1308 and 1403.[66] In 1250 William de Birmingham gained permission to hold a fair for three days about Ascensiontide. By 1400 a second fair was being held at Michaelmas[67] and in 1439 the then lord negotiated for the town to be free of the presence of royal purveyors.[68]

Early industries

Archaeological evidence of small-scale industries in Birmingham appears from as early as the 12th century,[69] and the first documentary evidence of craftsmen in the town comes from 1232, when a group of burgesses negotiating to be released from their obligation to help with the Lord's haymaking are listed as including a smith, a tailor and four weavers.[70] Manufacturing is likely to have been stimulated by the existence of the market, which would have provided a source of raw materials such as hides and wool, as well as a demand for goods from prosperous merchants in the town and from visitors from the countryside selling produce.[70] By 1332 the number of craftsmen in Birmingham was similar to that of other Warwickshire towns associated with industry such as Tamworth, Henley-in-Arden, Stratford-upon-Avon, and Alcester.[71]

Analysis of craftsmen's names in medieval records suggests that the major industries of medieval Birmingham were textiles, leather working and iron working,[71] with archaeological evidence also suggesting the presence of pottery, tile manufacture and probably the working of bone and horn.[72] By the 13th century there were tanning pits in use in Edgbaston Street;[73] and hemp and flax were being used for making rope, canvas and linen.[74] Kilns producing the distinctive local Deritend Ware pottery, examples of which can be seen in The Birmingham History Galleries, existed in the 12th and 13th centuries,[75] and skinners, tanners and saddlers are recorded in the 14th century.[71] The presence of slag and hearth bloom in pits excavated behind Park Street also suggests the early presence of working in iron.[76] The borough rentals of 1296 provide evidence of at least four forges in the town,[77] four smiths are mentioned on a poll tax return of 1379 and seven more are documented in the following century.[71] Although fifteen to twenty weavers, dyers and fullers have been identified in Birmingham up to 1347, this is not a significantly greater number of cloth-workers than that found in surrounding villages[71] and at least some of the cloth sold on the Birmingham market had rural origins.[78] This was the first local industry to benefit from mechanisation, however, and nearly a dozen fulling mills existed in the Birmingham area by the end of the 14th century, many converted from corn mills, but including one at Holford near Perry Barr that was purpose-built in 1358.[60]

While most manufactured goods would have been produced for a local market, there is some evidence that Birmingham was already a specialised and widely recognised centre of the jewellery trade during the medieval period. An inventory of the personal possessions of the Master of the Knights Templar in England at the time of their suppression in 1308 includes twenty two Birmingham Pieces: small, high value items, possibly jewellery or metal ornaments, that were sufficiently well known to be referred to without explanation as far away as London.[79] In 1343 three Birmingham men were punished for selling base metal items while asserting they were silver,[80] and there is documentary evidence of goldsmiths in the town in 1384 and 1460[81] – a trade that could not have been supported purely through local demand in a town of Birmingham's size.[82]

Medieval institutions and society

The growth of the urban economy of 13th century and early 14th century Birmingham was reflected in the development of its institutions. St Martin in the Bull Ring was rebuilt on a lavish scale around 1250[53] with two aisles, a clerestory and a 200 ft (61 m) high spire,[83] and two chantries were endowed in the church by wealthy local merchants in 1330 and 1347.[84] The Priory of St Thomas of Canterbury is first recorded in 1286, and by 1310 had received six major endowments of land totalling 60 acres (240,000 m2) and 27 smaller endowments.[83] The Priory was reformed in 1344 after criticism by the Bishop of Lichfield and a chantry was established in its chapel.[85] St John's Chapel, Deritend was established around 1380 as a chapel of ease of the parish church of Aston, with its priest supported by the associated Guild of St John, Deritend, which also maintained a school.[86] The parish of Birmingham gained its own religious guild with the foundation in 1392 of the Guild of the Holy Cross, which provided a social and political focus for the elite of the town[87] as well as supporting chaplains, almshouses, a midwife, a clock, the bridge over the River Rea and "divers ffoule and daungerous high wayes".[88]

Economic success also saw the town expand. New Street is first recorded in 1296,[89] Moor Street was created in the late 13th century and Park Street in the early 14th century.[90] Population growth was driven by rural migrants attracted by the opportunity of establishing themselves as traders, free from duties of agricultural labour.[91] Analysis of rentals suggest that two-thirds came from within 10 miles (16 km) of the town,[92] but others came from further afield, including Wales, Oxfordshire, Lincolnshire, Hampshire and even Paris.[93] There is also some evidence that the town may have had a Jewish population before the Edict of Expulsion of 1290.[94] Although medieval Birmingham was never incorporated as a self-governing entity independent of its manor,[53] the Borough – the built-up area – was governed separately from the Foreign – the open agricultural area to the west – from at least 1250.[95] The burgesses of the town elected the two bailiffs; the "commonalty of the town" is first recorded in 1296[89] and a pavage grant of 1318 was made out not to the Lord of the Manor but "to the bailiffs and good men of the town of Bermyngeham".[96] The town thus remained free of the restrictive trade guilds of fully chartered boroughs, but was free also from the constraints of a strict manorial regime.[97]

If the 12th and 13th centuries were a period of growth for the town, however, this ceased during the 14th century in the face of a series of calamities. The manorial court records of nearby Halesowen record a "Great Fire of Birmingham" between 1281 and 1313,[98] an event possibly reflected in late 13th century pits containing large quantities of charcoal and charred and burnt pottery found beneath Moor Street.[99] Famines of 1315 to 1322 and the Black Death of 1348–50 halted the growth in population[100] and the decline in archaeological evidence of pottery from the 14th and 15th centuries may indicate a prolonged period of economic hardship.[101]

Tudor and Stuart Birmingham, 1485–1680

The early modern town

The Tudor and Stuart eras marked a period of transition for Birmingham.[102] In the 1520s the town was the third largest in Warwickshire with a population of about 1,000 – a situation little changed from that two centuries earlier.[103] Despite a series of plagues throughout the 17th century,[104] by 1700 Birmingham's population had increased fifteenfold and the town was the fifth-largest in England and Wales,[105] with a nationally important economy based on the expanding and diversifying metal trades,[106] and a reputation for political and religious radicalism firmly established by its role in the English Civil War.[107]

The principal institutions of medieval Birmingham collapsed within the space of eleven years between 1536 and 1547.[102] The Priory of St Thomas was suppressed and its property sold at the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536,[108] with the Guild of the Holy Cross, the Guild of St John and their associated chantries also being disbanded in 1547.[109] Most significantly, the de Birmingham family lost possession of the manor of Birmingham in 1536, probably as a result of a feud between Edward de Birmingham and John Sutton, 3rd Baron Dudley.[110] After brief periods in the possession of the Crown and the Duke of Northumberland, the manor was sold in 1555 to Thomas Marrow of Berkswell.[111] Birmingham would never again have a resident Lord of the Manor,[112] and the district as a whole was to remain an area of weak lordship throughout the following centuries.[113] With local government remaining essentially manorial, the townspeoples' resulting high degree of economic and social freedom was to be a highly significant factor in Birmingham's subsequent development.[114]

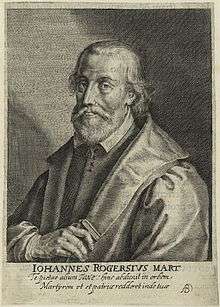

The period was also one of significant cultural development. Although the dissolution of the Guild of St John in Deritend saw the closure of its associated school, the former hall of the Guild of the Holy Cross in New Street, together with property worth £21 per year from its estate, was saved for the establishment of King Edward's Free Grammar School in 1552.[115] John Rogers, born in Deritend in 1500, became the town's first notable literary figure when he compiled and partially translated the Matthew Bible, the first complete authorised edition of the Bible to appear in the English language.[116] The first Birmingham library had been established by 1642,[117] the same year that Nathaniel Nye – the town's first known scientist – published his New Almanacke and Prognostication calculated exactly for the faire and populous Towne of Birmicham in Warwickshire.[118] Finally 1652 marks the first record of a Birmingham bookseller and the first Birmingham-published book: The Font Guarded, by the local puritan Thomas Hall.[119]

Industry and economy

Although the leather and textile trades were still major features of the Birmingham economy in the early 16th century,[120] the increasing importance of the manufacture of iron goods, as well as the interdependence between the manufacturers of Birmingham and the raw materials of the area that later became known as the Black Country, were recognised by the antiquary John Leland when he travelled through in 1538, providing the town's earliest surviving eyewitness description.[121]

The bewty of Bremischam, a good market towne in the extreme partes that way of Warwike-shire, is in one strete goynge up alonge almoste from the lefte ripe of the broke up a mene hille by the lengthe of a quartar of a mile. I saw but one paroche churche in the towne. There be many smithes in the towne that use to make knives and all maner of cuttynge tooles, and many lorimers that make byts, and a greate many naylors. So that a great parte of the towne is mayntayned by smithes. The smithes have there yren out of Staffordshire and Warwikeshire and see coale out of Staffordshire.

The importance of the iron trades increased further as the century progressed, with most of the fulling mills in the Birmingham area being converted into mills for grinding blades by the end of the century.[121] In 1586 William Camden described the town as "swarming with inhabitants, and echoing with the noise of the anvils, for here are great numbers of smiths and of other artificers in iron and steel, whose performances in that way are greatly admired both at home and abroad".[123]

Birmingham itself operated as the commercial hub for manufacturing activity which took place across the Birmingham Plateau, which itself formed the centre of a network of iron forges and furnaces stretching from South Wales and the Forest of Dean to Cheshire.[124] While 16th century deeds record nailers in Moseley, Harborne, Handsworth and King's Norton; bladesmiths in Witton, Erdington and Smethwick and scythesmiths in Aston, Erdington, Yardley and Bordesley; the ironmongers – the merchants who organised finance, supplied raw materials and marketed products, acting as middlemen between the smiths, their suppliers and their customers – were concentrated in the town of Birmingham itself.[125] Birmingham ironmongers are recorded selling the Royal Armouries large quantities of bills as early as 1514; by the 1550s Birmingham merchants were trading as far afield as London, Bristol and Norwich,[126] in 1596 Birmingham men are recorded selling arms in Ireland,[106] and by 1657 the reputation of the Birmingham metalware market had reached the West Indies.[127] By 1600 Birmingham ranked alongside London as one of the two great concentrations of iron merchants in the country, flourishing from its economic freedom and its proximity to manufacturers and raw materials, while London's traders remained under the control of a powerful corporate body.[106]

The concentration of iron merchants in Birmingham was significant in the development of the town's manufacturing as well as its commercial activities. Able to serve a wider market due to the town's extensive trading links, the metalworkers of Birmingham could diversify into increasingly specialised activities.[128] Over the course of the 17th century the lower-skilled nail, scythe and bridle trades – producing basic iron goods for local agricultural markets – moved west to the towns that would later make up the Black Country, while Birmingham itself focused on an increasingly wide range of more specialist, higher-skilled and more lucrative activities.[129] The hearth tax returns for Birmingham for 1671 and 1683 show the number of forges in the town increasing from 69 to 202,[130] but the later figures also show a far wider variety of trades, including hiltmakers, bucklemakers, scalemakers, pewterers, wiredrawers, locksmiths, swordmakers, and workers in solder and lead.[131] Birmingham's economic flexibility was already apparent at this early stage: workers and premises often changed trades or practiced more than one,[106] and the presence of a wide range of skilled manufacturers in the absence of restrictive trade guilds encouraged the development of entirely new industries.[132] The range of goods produced in late-17th century Birmingham, and its international reputation, were illustrated by the French traveller Maximilien Misson who visited Milan in 1690, finding "fine works of rock crystal, swords, heads of canes, snuff boxes, and other fine works of steel", before remarking "but they can be had better and cheaper at Birmingham".[133]

Politics, religion and civil war

By the early 17th century Birmingham's booming economy, dominated by the self-made merchants and manufacturers of the new metal trades rather than traditional landed interests; its expanding population and high degree of social mobility; and the almost complete absence from the area of a resident aristocracy; had seen it develop a new form of social structure very different from that of more traditional towns and rural areas: relationships were based more around pragmatic commercial linkages than the rigid paternalism and deference of feudal society, and the town was widely seen as one where loyalty to the traditional hierarchies of the established church and aristocracy was weak.[134] The first signs of Birmingham's growing political self-consciousness can be seen from the 1630s, when a series of puritan lectureships provided a focus for questioning the doctrines and structures of the Church of England and had a widespread influence throughout surrounding counties.[135] A 1640 puritan-inspired petition raised by the townspeople against the local Justice of the Peace Sir Thomas Holte provides the first evidence of conflict with the country gentlemen who dominated local government.[136]

The outbreak of the English Civil Wars in 1642 saw Birmingham emerge as a symbol of puritan and Parliamentarian radicalism,[136] with the Royalist Earl of Clarendon's History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England condemning the town as being "of as great fame for hearty, wilful, affected dis-loyalty to the king, as any place in England".[137] The arrival of 400 armed men from Birmingham was decisive in securing Coventry's refusal to admit Charles I in August 1642, which established Warwickshire as a Parliamentarian stronghold.[138] The march of the King and his army south from Shrewsbury in the days leading up to the Battle of Edge Hill in October 1642 met strong local resistance, with troops headed by Prince Rupert of the Rhine and the Earl of Derby being ambushed by local trainbands in Moseley and King's Norton, and the King's baggage train attacked by Birmingham townspeople and his personal possessions plundered and transported to Warwick Castle while the King stayed with the Royalist Sir Thomas Holte at Aston Hall.[136] The strategic importance of Birmingham's metal trades was also significant: one report suggested that the town's main mill had manufactured 15,000 swords solely for the use of Parliamentarian forces.[139]

Royalist revenge was exacted on Easter Monday, 3 April 1643, when Prince Rupert returned to Birmingham with 1,200 cavalry, 700 footsoldiers and 4 guns. Twice repulsed by the small force of 200 defenders behind hastily erected earthworks, the Royalist cavalry outflanked the defences and overran the town in the Battle of Birmingham, before burning 80 houses and leaving behind the naked corpses of fifteen townspeople. Although the Royalist victory was militarily insignificant, and came at the expense of the death of the Earl of Denbigh, the resistance of a largely civilian force against the royalist cavalry, and the subsequent sack of the town, presented the Roundheads with a major propaganda boost that was eagerly exploited by a series of widely circulated pamphlets.[140]

During the later years of the Civil War the subversive potential of Birmingham's manufacturing-based society was personified by the local parliamentarian colonel John "Tinker" Fox, who recruited a garrison of 200 men from the Birmingham area and occupied Edgbaston Hall from 1643.[141] From there he attacked and removed the Royalist garrison from nearby Aston Hall, established control over the countryside leading out to Royalist Worcestershire, and launched a series of audacious raids as far afield as Bewdley.[142] Highly active, and operating largely independently of the parliamentarian hierarchy, to Royalists Fox came to symbolise a dangerous and uncontrolled overturning of the established order, with his background in the Birmingham metal trades seeing him caricatured as a tinker.[143] By 1649 his national notoriety was such that he was widely rumoured to have been Charles I's executioner.[144]

The Midlands Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, 1680–1791

Enlightenment, Nonconformism and industrial innovation

The 18th century saw the sudden emergence of Birmingham at the forefront of worldwide developments in science, technology, medicine, philosophy and natural history as part of the cultural transformation now known as the Midlands Enlightenment.[145] By the second half of the century the town's leading thinkers – particularly members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham such as Joseph Priestley, James Keir, Matthew Boulton, James Watt, William Withering and Erasmus Darwin – had become widely influential participants in the Republic of Letters, the free circulation of ideas and information among the developing pan-European and trans-Atlantic intellectual elite.[146] The Lunar Society was "the most important private scientific association in eighteenth-century England"[147] and the Midlands Enlightenment "dominated the English experience of enlightenment",[148] but also maintained close links with other major centres of the Age of Enlightenment, particularly the universities of the Scottish Enlightenment,[149] the Royal Society in London, and scientists, philosophers and academicians in France, Sweden, Saxony, Russia and America.[150]

This "miracle birth" has traditionally been seen as a result of Birmingham's status as a stronghold of religious Nonconformism, creating a free-thinking culture unconstrained by the established Church of England. This accords with wider historical theories such as the Merton thesis and the Weber thesis, that see Protestant culture as a major factor in the rise of experimental science and industrial capitalism within Europe.[151] Birmingham had a vigorous and confident Nonconformist community by the 1680s, at a time when freedom of worship for Nonconformists nationally had yet to be granted; and by the 1740s this had developed into an influential group of Rational Dissenters.[152] Around 15% of households in Birmingham were members of Nonconformist congregations in the mid-18th century, compared to a national average of 4–5%.[153] Presbyterians and Quakers in particular also had a level of influence within the town that was disproportionate to their numbers, customarily holding the position of Low Bailiff – the most powerful position in the town's local government – from 1733, and making up over a quarter of the Street Commissioners appointed in 1769, despite being legally barred from holding office until 1828.[154] Despite this, Birmingham's Enlightenment was by no means a purely Nonconformist phenomenon: the members of the Lunar Society had a wide range of religious backgrounds,[155] and Anglicans formed a majority of all sections of Birmingham society throughout the period.

Recent scholarship no longer sees the Midlands Enlightenment as primarily having an industrial or technological focus.[156] Analysis of the subject-matter of Lunar Society meetings shows that its main concern was with pure scientific investigation rather than manufacturing,[157] and the influence of Midlands Enlightenment thinkers can be seen in areas as diverse as education,[158] the philosophy of mind,[159] Romantic poetry,[160] the theory of evolution[161] and the invention of photography. A distinctive and significant feature of the Midlands Enlightenment, however, that partly resulted from Birmingham's unusually high level of social mobility, was the close relationship between the practitioners of theoretical science and those of practical manufacturing.[162] The Lunar Society included industrialists such as Samuel Galton, Jr. as well as intellectuals such as Erasmus Darwin and Joseph Priestley;[163] scientific lecturers such as John Warltire and Adam Walker communicated basic Newtonian principles widely to the town's manufacturing classes;[164] and men such as Matthew Boulton, James Keir, James Watt and John Roebuck were simultaneously highly regarded both as scientists and as technologists, and in some cases also as businessmen.[165] The intellectual climate of 18th century Birmingham was therefore unusually conducive to the transfer of knowledge from the pure sciences to the technology and processes of manufacturing, and the feeding back of the results of this to create a "chain reaction of innovation".[166]

The Midlands Enlightenment therefore occupies a key cultural position linking the expansion of knowledge of the earlier Scientific Revolution with the economic expansion of the Industrial Revolution.[167] 18th century Birmingham saw the widespread and systematic application of reason, experiment and scientific knowledge to manufacturing processes to an unprecedented degree, resulting in a series of technological and economic innovations that transformed the economic landscape of a wide variety of industries, laying many of the foundations for modern industrial society.[168] In 1709 Abraham Darby I, who had trained as an apprentice in Birmingham and worked in Bristol for the Birmingham ironmonger Sampson Lloyd,[169] moved to Coalbrookdale in Shropshire and established the first blast furnace to successfully smelt iron with coke.[170] In 1732 Lewis Paul and John Wyatt invented roller spinning – the "one novel idea of the first importance" in the development of the mechanised cotton industry[171] – and in 1741 they opened the world's first cotton mill in Birmingham's Upper Priory.[172] In 1765 Matthew Boulton opened the Soho Manufactory, pioneering the combination and mechanisation of previously separate manufacturing activities under one roof through a system known as "rational manufacture".[173] By the end of the decade this was the largest manufacturing unit in Europe with over 1,000 employees, and the foremost icon of the emerging factory system. John Roebuck's 1746 invention of the lead chamber process first enabled the large-scale manufacture of sulphuric acid,[174] while James Keir pioneered the manufacture of alkali at his plant in Tipton;[175] between them these two developments marked the birth of the modern chemical industry.[176] The most notable technological innovation of the Midlands Enlightenment, however, was the 1775 development by James Watt and Matthew Boulton of the industrial steam engine, which incorporated four separate technical advances to allow it to cheaply and efficiently generate the rotary motion needed to power manufacturing machinery.[177] Freeing the productive potential of society from the limited capacity of hand, water and animal power, this was arguably the pivotal development of the entire industrial revolution, without which the spectacular increases in economic activity of the subsequent century would have been impossible.[178]

Commercial and industrial expansion

The explosive industrial growth of Birmingham started before that of the textile towns of the North of England and can be traced as far back as the 1680s.[179] Birmingham's population quadrupled between 1700 and 1750.[180] By 1775 – before the start of the mechanisation of the Lancashire cotton trade[181] – Birmingham was already the third most-populous town in England, smaller only than the older southern ports of London and Bristol and growing faster than any of its rivals.[182] As early as 1791 Birmingham was being described by the economist Arthur Young as "the first manufacturing town in the world".[183]

The factors that drove Birmingham's rapid industrialisation were also different from those behind the later development of textile manufacturing towns such as Manchester, whose spectacular growth from the 1780s onwards was based on the economies of scale inherent in mechanised manufacture: the ability of a low-wage, unskilled labour force to produce bulk commodities such as cotton in huge quantities. Although the developments that enabled this transformation – roller spinning, the factory system and the industrial steam engine – often had Birmingham origins,[184] they had little role in Birmingham's own expansion. Birmingham's relatively inaccessible location meant that its industries were dominated by the production of a wide variety of small, high value metal items – from buttons and buckles to guns and jewellery. Its economy was characterised by high wages and a diverse range of specialised skills that were not susceptible to wholesale automation.[185] The small-scale workshop, rather than the large factory or mill, remained the typical Birmingham manufacturing unit throughout the 18th century,[186] and the use of steam power was not economically significant in Birmingham until the 1830s.[187]

Rather than low wages, efficiency and scale, Birmingham's manufacturing growth was fuelled by a highly skilled workforce, specialisation, flexibility and, above all, innovation.[188] The low barriers to entry to the Birmingham trades gave the town a high degree of social mobility and a distinctly entrepreneurial economy;[189] the contemporary William Hutton described trades that "spring up with the expedition of a blade of grass, and, like that, wither in the summer".[190] In terms of manufacturing technology Birmingham was by far the most inventive town of the era: between 1760 and 1850 Birmingham residents registered over three times as many patents as those of any other town or city.[191] Despite the landmark inventions of engineers such as James Watt, most of these developments are better characterised as part of a continuous flow of small-scale technological improvements.[192] Matthew Boulton remarked in 1770 how "by the many mechanical contrivances and extensive apparatus wh we are possess'd of, our men are enabled to do from twice to ten times the work that can be done without the help of such contrivances".[193] Innovation also took place in production processes, particularly in the development of an extreme division of labour.[194] Contemporary sources noted that in Birmingham even simple products such as buttons would pass through between fifty and seventy different processes, performed by a similar number of different workers.[195] The resulting competitive advantage was noticed by Lunar Society member Richard Lovell Edgeworth when he visited Paris, observing that "each artisan in Paris ... must in his time 'play many parts', and among these many to which he is incompetent", concluding that "even supposing French artisans to be of equal ability and industry with English competitors, they are left at least a century behind".[196]

Innovation also extended to Birmingham's products, which were increasingly tailored to its merchants' national and international connections.[197] During the first half of the century growth was largely driven by the domestic market and based on increased national prosperity,[198] but foreign trade was important even in the mid-century[199] and was the dominant factor from the 1760s and 1770s,[200] dictated by the markets and fashions of London, France, Italy, Germany, Russia and the American colonies.[197] The adaptability and speed to market of the Birmingham economy allowed it to be heavily influenced by fashion[197] – the market for buckles collapsed in the late 1780s, but workers transferred skills to brass or button trades.[201] Birmingham manufacturers sought design leadership in fashionable circles in London or Paris, but then priced their goods to appeal to the emerging middle class consumer economy;[202] "for the London season the Spitalfields silk weavers produced each year their new designs, and the Birmingham toy-makers their buttons, buckles, patchboxes, snuff boxes, chatelaines, watches, watch seals ... and other jewellery."[203] Competitive pressure drove Birmingham manufacturers to adopt new products and materials:[204] the town's first glasshouse opened in 1762,[205] manufacture in papier-mâché developed from the award of a patent to Henry Clay in 1772, foreshadowing the Birmingham invention of plastics the following century,[206] the minting of coins grew from 1786.[206]

In addition to its own specialist manufacturing role, Birmingham retained its position as the commercial and mercantile centre for an integrated regional economy that included the more basic manufacturing and raw material production areas of Staffordshire and Worcestershire.[207] The demand for capital to feed rapid economic expansion saw the town become a major financial centre with extensive international connections.[208] During the early 18th century finance was largely provided by the iron merchants and by extensive systems of trade credit between manufacturers;[209] it was an iron merchant Sampson Lloyd and major manufacturer John Taylor who combined to form the town's first bank – the early Lloyds Bank – in 1765.[210] Further establishments followed and by 1800 the West Midlands had more banking offices per head than any other region in Britain, including London.[208] Birmingham's booming economy gave the town a growing professional sector, with the number of physicians and lawyers increasing by 25% between 1767 and 1788.[211] It has been estimated that between a quarter and a third of Birmingham's inhabitants could be thought of as middle class in the last quarter of the 18th century[212] and this fuelled a large growth in the demand for tailors, mercers and drapers.[213] Trade directories reveal that there more drapers than edge tool makers in 1767,[214] and insurance records from 1777 to 1786 suggest that well over half of local businesses were engaged in the trading or service sectors rather than directly in industry.[215]

Enlightenment society

Georgian Birmingham was marked by the dramatic growth of the vigorous public sphere for the exchange of ideas that was the hallmark of enlightenment society. Most characteristic was the development of clubs, taverns and coffeehouses as places for free association, cooperation and debate, often crossing lines of social class and status.[216] Although the exceptional historic influence of the Lunar Society of Birmingham has made it much the best-known, the contemporary William Hutton described hundreds of such associations in Birmingham with thousands of members,[217] and the German visitor Philipp Nemnich commented late in the century that "the inhabitants of Birmingham are fonder of associations in clubs than almost any other place I know".[218] Particularly notable examples included Freeth's Coffee House, one of the most celebrated meeting places of Georgian England;[219] Ketley's Building Society, the world's first building society, founded at the Golden Cross in Snow Hill in 1775; the Birmingham Book Club, whose radical politics saw it nicknamed the "Jacobin Club",[220] and which alongside other debating societies such as the Birmingham Free Debating Society and the Amicable Debating Society played a prominent role in the growing expression of popular political consciousness within the town;[221] and the more conservative Birmingham Bean Club, a dining club uniting leading loyalist figures in the town with prominent landowners from the surrounding counties, which played a prominent role in the emergence of a distinct "Birmingham interest" in regional politics from 1774.[222]

The printed word represented another expanding medium for the exchange of ideas. Georgian Birmingham was a highly literate society with at least seven booksellers by 1733, the largest in 1786 claiming a stock of 30,000 titles in several languages.[223] These were supplemented by eight or nine commercial lending libraries established over the course of the 18th century,[224] to the extent that it was claimed in the later part of the century that Birmingham's population of around 50,000 read 100,000 books per month.[225] More specialist libraries included St. Philip's Parish Library established in 1733, and the Birmingham Library, established for research purposes in 1779 by a largely dissenting group of subscribers.[226] Birmingham had been a centre for the printing and publishing of books since the 1650s[227] but the rise of John Baskerville and the nine other printers he attracted to the town in the 1750s saw this achieve international significance.[228] The town's first newspaper was the Birmingham Journal founded in 1732; it was short-lived but notable as the vehicle for the first published work of Samuel Johnson.[229] Aris's Birmingham Gazette, founded in 1741, became "one of the most lucrative and important provincial papers" of 18th century England,[230] and by the 1770s circulated as far afield as Chester, Birmingham and London.[231] The more radical Swinney's Birmingham Chronicle, which caused controversy in 1771 by serialising Voltaire's Thoughts on Religion,[232] boasted in 1776 that it circulated across nine counties and was "filed by coffeehouses in practically every centre of any size from Edinburgh southwards".[233] News from outside the town also circulated widely: Freeth's Coffeehouse in 1772 maintained an archive of all the London newspapers going back 37 years and received direct personal reports of proceedings in Parliament,[234] while Overton's Coffeehouse in New Street in 1777 had the London papers delivered by express messenger the day after their publication, also having available all of the main country, Irish and European papers, and Parliamentary division lists.[235]

Birmingham's booming economy attracted immigrants from a wide area, many of whom retained freeholds – and thus votes – in their previous constituencies, giving Birmingham politics a wide electoral influence despite the town having no parliamentary representation of its own.[236] A distinct and powerful "Birmingham interest" emerged decisively with the election of Thomas Skipwith at the Warwickshire by-election of 1769,[237] and over following decades candidates for seats as far afield as Worcester, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Leicester and Lincoln sought support in the town.[238]

Transport and the growth of the town

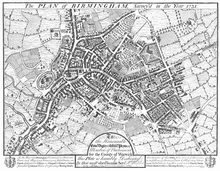

The first map of Birmingham was produced in 1731 by William Westley, though the year before, he produced the first documentation of a newly constructed square named Old Square.[239] It became one of the most prestigious addresses in Birmingham. This was not the first map to show Birmingham, something that had been done in 1335, albeit showing Birmingham as a small symbol.[240] Birmingham was again surveyed in 1750 by S. Bradford.[241]

Until the 1760s, Birmingham's local government system, consisted of manorial and parish officials, most of whom served on a part-time and honorary basis. However this system proved completely inadequate to cope with Birmingham's rapid growth. In 1768, Birmingham gained a rudimentary local government system, when a body of "Commissioners of the Streets" was established, who had powers to levy a rate for functions such as cleaning and street lighting. They were later given powers to provide policing and build public buildings.[37]

From the 1760s onwards, Birmingham became a centre of the canal system. The canals provided an efficient transport system for raw materials and finished goods, and greatly aided the town's industrial growth.

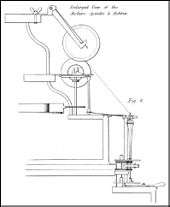

The first canal to be built into Birmingham, was opened in November 1769 and connected Birmingham with the coal mines at Wednesbury in the Black Country.[242] Within a year of the canal opening, the price of coal in Birmingham had fallen by 50%.[243]

The canal network across Birmingham and the Black Country expanded rapidly over the following decades, with most of it owned by the Birmingham Canal Navigations Company. Other canals such as the Worcester and Birmingham Canal, the Birmingham and Fazeley Canal, the Warwick and Birmingham Canal (now the Grand Union) and the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal linked Birmingham to the rest of the country. By 1830, some 160 miles (260 km) of canal had been constructed across the Birmingham and Black Country area.[244]

Due to Birmingham's vast array of industries, it was nicknamed "workshop of the World". The expansion of the population of the town and the increased prosperity led to it acquiring a library in 1779, a hospital in 1766 and a variety of recreational institutions.[245]

Victorian Birmingham 1832–1914

Horatio Nelson and the Hamiltons visited Birmingham. Nelson was fêted, and visited Matthew Boulton on his sick-bed at Soho House, before taking a tour of the Soho Manufactory and commissioning the Battle of the Nile medal. In 1809, a statue of Horatio Nelson by Richard Westmacott Jr. was erected by public subscription. It still stands, in the Bull Ring, albeit on a 1960s plinth.

The Birmingham Manor House and its moat were demolished and removed in 1816.[246] The site was constructed upon to create the Smithfield Markets, which concentrated various marketing activities upon one area close to the Bull Ring which had developed into a retail-led area.

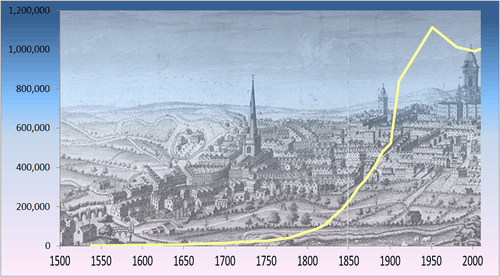

At the beginning of the 19th century, Birmingham had a population of around 74,000. By the end of the century it had grown to 630,000. This rapid population growth meant that by the middle of the century Birmingham had become the second largest population centre in Britain.[247]

Railways arrive

Railways arrived in Birmingham in 1837 with the opening of the Grand Junction Railway which linked Birmingham with Manchester and Liverpool. The following year the London and Birmingham Railway opened, linking to the capital. This was soon followed by the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway and the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway.[248]

These all initially had separate stations around Curzon Street. However, in the 1840s, these early railway companies had merged to become the London and North Western Railway and the Midland Railway respectively. The two companies jointly constructed Birmingham New Street which was opened in 1854, and Birmingham became a central hub of the British railway system.

In 1852, the Great Western Railway (GWR) arrived in Birmingham, and a second smaller station, Birmingham Snow Hill was opened. The GWR line linked the city with Oxford and London Paddington.

Political reform

Also in the 1830s, due to its growing size and importance, Birmingham was granted Parliamentary representation by the Reform Act of 1832. The new Birmingham constituency was created with two MPs representing it. Thomas Attwood and Joshua Scholefield both Liberals, were elected as Birmingham's first MP's.

In 1838, local government reform meant that Birmingham was one of the first new towns to be incorporated as a municipal borough by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835.[249] This allowed Birmingham to have its first elected town council. The council initially worked alongside the existing Street Commissioners, until they were wound up in 1851.

Industry and commerce

Birmingham's growth and prosperity was based upon metalworking industries, of which many different kinds existed.

Birmingham became known as the "City of a thousand trades" because of the wide variety of goods manufactured there – buttons, cutlery, nails and screws, guns, tools, jewellery, toys, locks, and ornaments were amongst the many products manufactured.

For most of the 19th century, industry in Birmingham was dominated by small workshops rather than large factories or mills.[250] Large factories became increasingly common towards the end of the century when engineering industries became increasingly important.

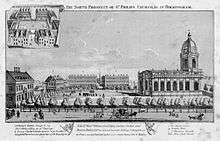

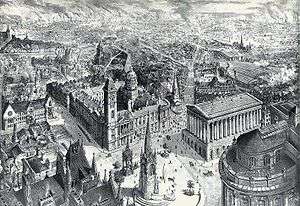

The industrial wealth of Birmingham allowed merchants to fund the construction of some fine institutional buildings in the city. Some buildings of the 19th century included: the Birmingham Town Hall built in 1834, the Birmingham Botanical Gardens opened in 1832, the Council House built in 1879, and the Museum and Art Gallery in the extended Council House, opened in 1885.

The mid-19th century saw major immigration into the city from Ireland, following the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849).

Birmingham became a county borough and a city in 1889.[251]

Improvements

As in many industrial towns during the 19th century, many of Birmingham's residents lived in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions. During the early-to-mid-19th century, thousands of back-to-back houses were built to house the growing population, many of which were poorly built and badly drained, and many soon became slums.[252]

In 1851, a network of sewers was built under the city which was connected to the River Rea,[253] although only new houses were connected to it, and many older houses had to wait decades until they were connected.

Birmingham gained gas lighting in 1818, and a water company in 1826, to provide piped water, although clean water was only available to people who could pay. Birmingham gained its first electricity supply in 1882. Horse-drawn trams ran through Birmingham from 1873, and electric trams from 1890.[37]

In the mid 1840s, the charismatic nonconformist preacher George Dawson began to promote a doctrine of social responsibility and enlightened municipal improvement that became known as the Civic Gospel. His philosophy inspired a group of reformers – including Joseph Chamberlain, Jesse Collings, George Dixon, and others – who from the late 1860s onwards began to be elected to the Town Council as Liberals, and to apply these ideas in practice. This period reached its peak during the mayoralty of Chamberlain, 1873–1876. Under his leadership, Birmingham was transformed, as the council introduced one of the most ambitious improvement schemes outside London. The council purchased the city's gas and water works, and moved to improve the lighting and provide clean drinking water to the city, income from these utilities also provided a healthy income for the council, which was re-invested into the city to provide new amenities.

Under Chamberlain, some of Birmingham's worst slums were cleared. And through the city-centre a new thoroughfare was constructed, Corporation Street, which soon became a fashionable shopping street. He was instrumental in building of the Council House and the Victoria Law Courts in Corporation Street. Numerous public parks were also created, central lending and reference libraries were opened in 1865–6, and the city's Museum and Art Gallery in 1885. The improvements introduced by Chamberlain and his colleagues were to prove the blueprint for municipal government, and were soon copied by other cities. By 1890, a visiting American journalist could describe Birmingham as "the best-governed city in the world".[254] Although he resigned as mayor to become an MP, Chamberlain took close interest in the city for many years afterwards.

Birmingham's water problems were not fully solved through the creation of reservoirs in Walmley Ash, fed by Plants Brook.[255] Other larger reservoirs were constructed at Witton Lakes and Brookvale Park Lake to help ease the problems. The problems were finally solved, however, by Birmingham Corporation Water Department with the completion of a 73-mile (117 km) long Elan aqueduct was built to a reservoir in the Elan Valley in Wales; this project was approved in 1891 and completed in 1904.

Wartime and interwar Birmingham, 1914–1945

The First World War exacted a terrible human cost in Birmingham. More than 150,000 men from the city – over half of the male population – served in the armed forces[256] of whom 13,000 were killed and 35,000 wounded.[257] The onset of mechanised warfare also served to increase the strategic importance of Birmingham as a centre of industrial production, with the British Commander-in-Chief John French describing the war at its outset as "a battle between Krupps and Birmingham".[258] At the war's close the Prime Minister David Lloyd George also recognised the significance of Birmingham in the allied victory, remarking how "the country, the empire and the world owe to the skill, the ingenuity and the resource of Birmingham a deep debt of gratitude".[259] Some Birmingham men were conscientious objectors.

In 1918, the Birmingham Civic Society was founded to bring public interest to bear upon all proposals put forward by public bodies and private owners for building, new open spaces and parks, and any and all matters concerned with the amenities of the city. The society set about making suggestions for improvements in the city, sometimes designing and paying for improvements themselves and buying a number of open spaces and later gifting them to the city for use as parks.

After the Great War ended in 1918, the city council decided to build modern housing across the city to rehouse families from inner city slums. Recent boundary expansions which brought areas including Aston, Handsworth, Erdington, Yardley and Northfield within the city's boundaries provided extra space for housing developments. By 1939, the year that the Second World War broke out, almost 50,000 council houses had been built across the city within 20 years. Some 65,000 houses were also built for owner occupiers. New council estates built during this era included Weoley Castle between Selly Oak and Harborne, Pype Hayes near Erdington and the Stockfield Estate at Acocks Green.

In 1936, King Edward's Grammar School on New Street was demolished and moved to Edgbaston. The school had been on that site for 384 years. The site was later transformed into an office block which was destroyed in the bombing of the Second World War. It was later rebuilt and named "King Edward's House". It is used as an office block and on the ground floor as shops and restaurants.

In the First and Second World Wars, the Longbridge car plant switched to production of munitions and military equipment, from ammunition, mines and depth charges to tank suspensions, steel helmets, Jerricans, Hawker Hurricanes, Fairey Battle fighters and Airspeed Horsa gliders, with the mammoth Avro Lancaster bomber coming into production towards the end of WWII. The Spitfire fighter aircraft was mass-produced at Castle Bromwich by Vickers-Armstrong throughout the war.

Birmingham's industrial importance and contribution to the war effort may have been decisive in winning the war. The city was heavily bombed by the German Luftwaffe during the Birmingham Blitz in World War II. By the war's end 2,241 citizens had been killed by the bombing and over 3,000 seriously injured. 12,932 buildings were destroyed (including 300 factories) and thousands more damaged. The air raids also destroyed many of Birmingham's fine buildings. The council declared five redevelopment areas in 1946:[260]

- Duddeston and Nechells

- Summer Lane

- Ladywood

- Bath Row

- Gooch Street

Post-war prosperity, 1945–1975

Loss of independence and the prevention of growth

The defining feature of Birmingham's politics in the post-war era was the loss of much of city's independence.[261] World War II had seen a huge expansion in the role of central government in British life, and this pattern continued into the post-war years: for Birmingham, this meant major decisions about the city's future tended to be made outside the city, mainly in Westminster.[262] Planning, development and municipal functions were increasingly dictated by national policy and legislation; council finances came to be dominated by central government subsidies; and institutions such as gas, water and transport were taken out of the city's control.[263] Birmingham's unrivalled size and wealth may have given it more political influence than any other provincial city,[264] but like all such cities it was essentially subordinate to Whitehall; the days of Birmingham as a semi-autonomous city-state, with its leading citizens dictating the agenda of national politics, were over.[265]

This was to have major implications for the direction of the city's development. Up until the 1930s it had been a basic assumption of Birmingham's leaders that their role was to encourage the city's growth. Post-war national governments, however, saw Birmingham's accelerating economic success as a damaging influence on the stagnating economies of the North of England, Scotland and Wales, and saw its physical expansion as a threat to its surrounding areas[266] – "from Westminster's point of view [Birmingham] was too large, too prosperous, and had to be held in check".[267] A series of measures, starting with the Distribution of Industry Act 1945, aimed to prevent industrial growth in the "Congested Areas" – essentially the booming cities of London and Birmingham – instead encouraging the dispersal of industry to the economically stagnant "Development Areas" in the north and west.[268] The West Midlands Plan, commissioned by the Minister for Town and Country Planning from Patrick Abercrombie and Herbert Jackson in 1946, set Birmingham a target population for 1960 of 990,000, far less than its actual 1951 population of 1,113,000. This meant that 220,000 people would have to leave the city over the following 14 years, that some of the city's industries would have to be removed, and that new industries would need to be prevented from establishing themselves in the city.[269] By 1957 the council had explicitly accepted that it was obliged "to restrain the growth of population and employment potential within the city".[270]

With the city's power over its own destiny reduced, Birmingham's lost most of its political distinctiveness. The General Election of 1945 was the first for 70 years in which no member of the Chamberlain family stood for Birmingham.[271]

Economic boom and restriction

Birmingham's economy flourished in the 30 years that followed the end of the Second World War, its economic vitality and affluence far outstripping Britain's other major provincial cities.[272] Economic adaptation and restructuring over the previous half century had left the West Midlands well represented in two of the British economy's three major growth areas – motor vehicles and electrical equipment[273] – and Birmingham itself was second only to London for the creation of new jobs between 1951 and 1961.[274] Unemployment in Birmingham between 1948 and 1966 rarely exceeded 1%, and only exceeded 2% in one year.[275] By 1961 household incomes in the West Midlands were 13% above the national average,[276] exceeding even than those of London and the South East.[277]

This prosperity was achieved despite severe restrictions placed on the city's economy by central government, which explicitly sought to limit Birmingham's growth.[278] The Distribution of Industry Act 1945 prohibited all industrial development over a specific size without an "Industrial Development Certificate", in the hope that companies refused permission to expand in London or Birmingham would move instead to one of the struggling cities of the North of England.[279] At least 39,000 jobs were directly transferred out of the West Midlands by factory movement between 1960 and 1974,[280] and planning measures were instrumental in local firms such as the British Motor Corporation and Fisher and Ludlow expanding in South Wales, Scotland and Merseyside instead of Birmingham.[281] Government measures also acted indirectly to deter economic development within the city:[281] restrictions on the city's physical growth in an era of economic boom led to extremely high land prices and shortages of premises and development sites,[282] and moves to reduce the city's population led to labour shortages and escalating wages.[283]

Although employment in Birmingham's restricted manufacturing sector shrank by 10% between 1951 and 1966, this was more than made up during the early post-war period for by employment in the service sector, which grew from 35% of the city's workforce in 1951 to 45% in 1966.[284] As the commercial centre of the country's most successful regional economy, Central Birmingham was the main focus outside London for the post-war office building boom.[285] Service sector employment in the Birmingham conurbation grew faster than in any other region between 1953 and 1964, and the same period saw 3 million sq ft of office space constructed in the city centre and Edgbaston.[286] The city's economic boom saw the rapid growth of a substantial merchant banking sector, as major London and international banks established themselves within the city,[287] and professional and scientific services, finance and insurance also grew particularly strongly.[288] However this service sector growth itself attracted government restrictions from 1965. Declaring the growth in population and employment within Birmingham to be a "threatening situation", the incoming Labour Government of 1964 sought "to control the growth of office accommodation in Birmingham and the rest of the Birmingham conurbation before it got out of hand, in the same way as they control the growth of industrial employment".[286] Although the City Council had encouraged service sector expansion during the late 1950s and early 1960s, central government extended the Control of Office Employment Act 1965 to the Birmingham conurbation from 1965, effectively banning all further office development for almost two decades.[289]

These policies had a major structural effect on the city's economy. While government policy had limited success in preventing the growth of Birmingham's existing industries, it was much more successful in preventing new industries establishing themselves in the city.[290] Birmingham's economic success over the previous two centuries had been built on its economic diversity and its ongoing ability to adapt and innovate – attracting new businesses and developing new industries with its large supply of skilled labour and dynamic entrepreneurial culture – but this was exactly the process that government industrial location policy sought to prevent.[291] Birmingham's existing industries grew strongly and kept the economy buoyant, but growing local fears that the city's economy was becoming over-specialised were dismissed by central government, even though danger signs were growing by the early 1970s.[292] In 1950 Birmingham's economy could still be described as "more broadly based than that of any city of equivalent size in the world",[293] but by 1973 the West Midlands had an above-average reliance on large firms for employment,[294] and the small firms that remained were increasingly dependent as suppliers and sub-contractors to the few larger firms.[295] The "City of Thousand Trades" had become over-specialised on one industry – the motor trade – much of which by the 1970s had itself consolidated into a single company – British Leyland.[296] Trade union organisation grew and the motor industry in particular saw industrial disputes from the 1950s onwards.[275] A city that for most of its history had a reputation for weak trade unionism and strong cooperation between workers and management, developed a reputation for trade union militancy and industrial conflict.[297]

Despite more than 150,000 houses being built in the city for both the private and public sector since 1919, 20% of the city's homes were still deemed unfit for human habitation by 1954. 37,000 council properties had been built between 1945 and 1954 to rehouse families from the slums, but by 1970 the housing crisis was being eased as that figure had now exceeded 80,000.[298]

Planning and redevelopment

In the postwar years, a massive program of slum clearances took place, and vast areas of the city were re-built, with overcrowded "back to back" housing being replaced by high rise blocks of flats (the last remaining block of four back-to-backs have become a museum run by the National Trust).

Due largely to bomb damage, the city centre was also extensively re-built under the supervision of the city council's chief engineer Herbert Manzoni during the postwar years. He was assisted by the City Architect position which was held by several people.[299] Emblematic of this was the new Bull Ring Shopping Centre. Birmingham also became a centre of the national motorway network, with Spaghetti Junction. Much of the re-building of the postwar period would in later decades be regarded as mistaken, especially the large numbers of concrete buildings and ringroads which gave the city a reputation for ugliness.

Council house building in the first decade following the end of the Second World War was extensive; with more than 37,000 new homes being completed between then and the end of 1954. These included the first of several hundred multi-storey blocks of flats. Despite this, some 20% of the city's houses were still reported to be unfit for human habitation. As a result, mass council house building continued for some 20 years afterwards. The existing suburbs continued to expand, while several completely new estates were developed.

Castle Bromwich, which grew into a new town, was developed approximately six miles to the east of the town centre during the 1960s. Castle Vale, near the Fort Dunlop tyre factory to the north-east of the city centre, was developed in the 1960s as Britain's largest postwar housing estate; featuring a total of 34 tower blocks, although 32 of them had been demolished by the end of 2003 as part of a massive regeneration of the estate brought on by the general unpopularity and defects associated with such developments.[300]

In 1974, 21 people were killed and 182 others injured when two city-centre pubs were bombed by the Provisional Irish Republican Army.

In the same year as part of a local government reorganisation, Birmingham expanded again, this time taking over the borough of Sutton Coldfield to the north.[301] Birmingham lost its county borough status and instead became a metropolitan borough under the new West Midlands County Council. It was also finally removed from Warwickshire.

Immigration and cultural diversity

There were further waves of immigration from Ireland in the 1950s and 1980s as emigrants sought to escape the economic deprivation and unemployment in their homeland. There remains a strong Irish tradition in the city, most notably in Digbeth's Irish Quarter and in the annual St Patrick's Day parade, claimed to be the third-largest in the world after New York and Dublin.[302]

In the years following World War II, a major influx of immigrants from the Commonwealth of Nations changed the face of Birmingham, with large communities from Southern Asia and the Caribbean settling in the city,[303] turning Birmingham into one of the UK's leading multicultural cities.

The developments were not welcomed by everyone however – the right-wing Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell delivered his famous Rivers of Blood speech in the city on 20 April 1968.[304]

On the other hand, some arts prospered, especially music: Birmingham had thriving heavy metal (with bands such as Black Sabbath, Napalm Death and Judas Priest) and reggae scenes (notable locals including Steel Pulse, Pato Banton, Musical Youth, and UB40).