Antikyra

Antikyra or Anticyra (Greek: Αντίκυρα) is a port on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth in modern Boeotia, Greece. It appeared in the Homeric Catalogue of Ships as the primary port of ancient Phocis. It was famed in antiquity for its black and white hellebore. Antikyra was destroyed and rebuilt during the 4th- and 3rd-century BC wars of Macedonia and Rome and following a 7th-century AD earthquake. During the 14th century, it was held by Catalan mercenaries. It now forms a unit of the unified municipality of Distomo-Arachova-Antikyra and is a center of Greek aluminum production. The municipal unit has an area of 23.332 km2.[2] Its population in 2011 was 1,537.[1]

Antikyra Αντίκυρα | |

|---|---|

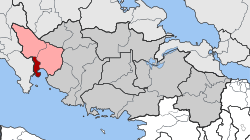

Antikyra Location within the regional unit  | |

| Coordinates: 38°23′N 22°38′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Central Greece |

| Regional unit | Boeotia |

| Municipality | Distomo-Arachova-Antikyra |

| • Municipal unit | 23.332 km2 (9.009 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 1,537 |

| • Municipal unit density | 66/km2 (170/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Vehicle registration | ΒΙ |

| Website | www.antikyra.gr |

Name

Antikyra has been (erroneously) identified with the Cyparissus (Ancient Greek: Κυπάρισσος, romanized: Kyparissos, lit. "Cypress") which appears in the Homeric Catalogue of Ships as the primary port of ancient Phocis. It became known as Antikirrha or Anticirrha (Ἀντίκιρρα)[3][4] from its position on the opposite side of a peninsula from Cirrha, Delphi's port on the Gulf of Corinth. This name then became Antikyrrha or Anticyrrha (Ἀντίκυρρα)[5] and then Antikyra. The last was followed by the Romans, Latinized as Anticyra. During its period under the Catalans, it was known as Port de Arago. Under the Ottomans, it became known as Aspra Spitia (Greek: Άσπρα Σπίτια) for its white houses[6] but its former name was restored in the early 20th century. Under the former BGN/PCGN standard, it was romanized as Andikira in America and the United Kingdom until 1996.

Geography

Antikyra is situated on the Bay of Antikyra (Latin: Anticyranus Sinus) on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth.[7] It lies 2 or 3 kilometers (1.2 or 1.9 mi) southwest of Paralia Distomou (also formerly known as "Aspra Spitia") and 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) southeast of Desfina. It is separated from Delphi by Mount Cirphis and from the Crissaean Gulf by the Opus peninsula (Latin: Opus Promontorium). The municipal unit also contains the villages of Agia Sotira and Agios Isidoros.

History

Ancient

It was a town of considerable importance in ancient times.[8] In antiquity, Antikyra was associated with the still-older settlement of Kyparissos which was noted as the primary port of Mycenaean Phocis in Homer's Iliad. The name literally means "cypress" but was glossed as deriving from the town's mythical founder Cyparissus, son of Orchomenus and brother of Minyas. The Catalogue of Ships states the Phocians who joined the Trojan War sailed from Kyparissos to join the main fleet at Aulis before it sailed for Troy.[9] The reputed graves of the heroes Schedios and Epistrophos, the Phocian admirals, were maintained through Roman times.[10]

The name Antikyra was said to have derived from an "Antikyreos" or "Anticyreus" who cured Hercules's insanity with local hellebore.[11][12] Black and white hellebore were the main reason for the town's fame in the ancient world.[7] Both grew nearby and were regarded by Greek medicine as cures for forms of insanity, melancholy, gout, and epilepsy.[13][14][15][16] The circumstance gave rise to a number of Greek and Latin expressions, like Αντικυρας σε δει or "naviget Anticyram," and to frequent allusions in Greek and Roman literature.[7] Pausanias claims that black hellebore was used as a laxative, whilst white hellebore was used as an emetic.[17]

Antikyra was destroyed in 346 BC by Philip II of Macedon amid the Third Sacred War.[18][19] It recovered enough to quickly begin construction of a temple to Artemis with a cult statue commissioned to Praxiteles by 330 BC.[20] Antikyra was then besieged, destroyed, and rebuilt several times during the Roman Republic's Macedonian Wars. In 198 BC, it was sacked by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, who choose it as winter base for his army.[21]

During the 2nd century BC, Antikyra struck autonomous bronze coins with the head of Poseidon on the obverse and Artemis bearing a torch and an arch on the reverse.[22]

Pausanias visited the city during the third quarter of the 2nd century and gave a detailed account of it in his Description of Greece. He notes the grave of Schedios and Epistrophos, a temple to Poseidon with a bronze statue of the god standing with one foot resting on a dolphin, a hand upon this thigh and a trident in his other hand,[23] two gymnasia (one including a statue of Xenodamos, who won the pangration at the Olympics in AD 67 owing to the participation of the emperor Nero), an agora with many bronze statues, a sheltered well, and two temples of Artemis outside the town walls. One was dedicated to Artemis Diktynna; the other held Praxiteles's sculpture and, according to a newly discovered inscription, was dedicated to Artemis Eileithyia.[24][25]

Medieval

Under the Byzantines, the city served as a bishopric. (A large 5-nave basilica with a mosaic floor was unearthed in the 1980s.) A large earthquake destroyed most of the city around AD 620. During the 14th century, the city was named Port de Arago while its fortress was held by the Catalans, probably under the aegis of the county of Salona (mod. Amphissa). It became known as Aspra Spitia[7] or Asprospitia[26] under the Turks.

Modern

Aspra Spitia's connection with the ancient Antikyra was established by William Martin Leake in 1806 when he found an inscription mentioning its name. The area was subsequently excavated by Lolling, Dittenberger, Fossey, the 10th Archaeological Ephorate, and the 1st Byzantine Ephorate. During this period, an archaic temple of Athena was discovered, along with its severe style bronze idol, a large part of the 4th-century BC ashlar fortification with 2 rectangular towers, and an early Christian bath with a hypocaust.[27]

In 1836, after Greek independence, the municipality Antikyraia was established, containing the villages Desfina (the seat of the municipality), Aspra Spitia and Moni Agiou Ioannou Prodromou.[28] In 1912, the municipality was replaced by the new community Desfina. Antikyra became a separate community in 1929, but was merged back into Desfina in 1935.[29] The community Antikyra was re-established in 1943.[30] In the 1950s and '60s, Aluminum of Greece developed the country's largest aluminum plant to exploit nearby bauxite deposits.[31] A new town was developed for its workers under the name Aspra Spitia; this is now known as Paralia Distomou. Greenpeace has complained of the effects of the red mud dumped into the bay from the plant.[32] At the 2010 Kallikratis reform, Antikyra was merged with its neighbors to form Distomo-Arachova-Antikyra.[30][33]

Population

| Year | Town population | Community population |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 2,045 | - |

| 1991 | 2,271 | - |

| 2001 | 2,812 | 2,984 |

| 2011 | 1,448 | 1,537 |

See also

Notes

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- Dicaearch.

- Strabo

- Eustath.

- Cramer 1828, p. 157.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 124.

-

- Homer, Il. II.519.

- "Σχεδίος (Μυθολ.)". Μεγάλη Ελληνική Εγκυκλοπαίδεια. Athens - Greece: "Pyrsos" Co. Ltd. 1933. p. 684.

- Ptolemy, Geography, ΙΙ.184.12.

- Stephen of Byzantium, "Antikyra".

- Dioscorides, De materia medica, IV.148-152, 162

- Pliny, N.H., XXII.64, XXV.21

- Ptolemaeus, Geogr. Hyph. ΙΙ 184. 12. Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. «Aντίκυρα»

- Hahnemann 1812.

- Pausanias 10.36.7

- Diodorus Siculus, XVI.59-60.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, Χ.3.1-3.

- Rizzo 1932, p. 13; Lacroix 1949, pp. 309–310; Corso 1988, pp. 182–184; and Rolley 1999, p. 244.

- Polybius, XVIII.28, 45.7, XXVII.14, 16.6.

- Sideris 2001, pp. 122-123.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 10.36.8.{{{2}}}.{{{3}}}.

- RE, “Diktynna”, col. 584-588.

- Dasios 1997, p. 450.

- Arrowsmith 1832, p. .

- Sideris 2001, pp. 114-120.

- ΦΕΚ 22Α - 18/01/1934, Government Gazette, p. 38

- "Κ. Δεσφίνης". EETAA local government changes. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Κ. Αντικύρας". EETAA local government changes. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Greece: Aluminum under Pressure", Time, 11 March 1966.

- Proposal for the Creation of a Marine Reserve in the Corinthian Bay (PDF), Greenpeace.

- Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (in Greek)

References

- Arrowsmith, John (1832), Turkey in Europe

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 124

- Corso, A. (1988), Prassitele. Fonti Εpigrafiche e letterarie. Vita et opere, Vol. 1 (in Italian), Roma, pp. 182–184

- Cramer, John Anthony (1828), A Geographical and Historical Description of Ancient Greece with a Map and a Plan of Athens, Vol. II, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Dasios, F. (1997), "Antikyra", ADelt, No. 52, p. 450.

- Hahnemann, Samuel (1812), Dissertatio Historico-Medica de Helleborismo Veterum ["Medical Historical Dissertation on the Helleborism of the Ancients"] (in Latin), Leipzig: reprinted 2004 in New Delhi as pp. 569–615 of Robert Ellis Dudgeon's Lesser Writings of Samuel Hahnemann, ISBN 9788170211242

- Lacroix, L. (1949), Les reproductions de statues sur les monnaies grecques (in French), Liége, pp. 309–310

- Rizzo, G.-E. (1932), Prassitele, Milan, p. 13. (in Italian)

- Rolley, C. (1999), La Sculpture Grecque 2, La période classique (in French), Paris, p. 244

- Sideris, Athanasios (2001), "Antikyra: An ancient Phokian City", Emvolimo, No. 43-44 (in Greek), pp. 110–125

- Sideris, Athanasios (2014), "Αντίκυρα. Iστορία & Αρχαιολογία [Antikyra: History & Archeology]", Δήμος Διστόμου - Αράχωβας – Αντίκυρας (in Greek), Athens, ISBN 978-618-81336-0-0

Bibliography

- , 'Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. II, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, p. 127.

- Sideris Α., "Antikyra: An ancient Phokian City", Emvolimo 43–44 (Spring–Summer 2001), pp. 110–125 (in Greek)

Further reading

- Sideris A., Antikyra. History and Archaeology, (Athens 2014), ISBN 978-618-81336-0-0 (fulltext book online, bilingual GR & EN edition)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (9th ed.) article Anticyra. |

- Official website (in Greek)

- Antikyra on GTP Travel Pages