Tribal Hidage

The Tribal Hidage is a list of thirty-five tribes that was compiled in Anglo-Saxon England some time between the 7th and 9th centuries. It includes a number of independent kingdoms and other smaller territories, and assigns a number of hides to each one. The list is headed by Mercia and consists almost exclusively of peoples who lived south of the Humber estuary and territories that surrounded the Mercian kingdom, some of which have never been satisfactorily identified by scholars. The value of 100,000 hides for Wessex is by far the largest: it has been suggested that this was a deliberate exaggeration.

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe

Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians

East Asia Europe East Asia Europe

Indo-Aryan Iranian

|

|

Religion and mythology

Indo-Aryan Iranian Others Europe

|

|

The original purpose of the Tribal Hidage remains unknown: it could be a tribute list created by a king, but other purposes have been suggested. The hidage figures may be symbolic, reflecting the prestige of each territory, or they may represent an early example of book-keeping. Many historians are convinced that the Tribal Hidage originated from Mercia, which dominated southern Anglo-Saxon England until the start of the 9th century, but others have argued that the text was Northumbrian in origin.

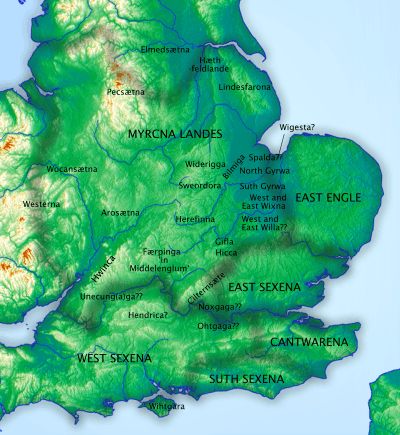

The Tribal Hidage has been of importance to historians since the middle of the 19th century, partly because it mentions territories unrecorded in other documents. Attempts to link all the names in the list with modern places are highly speculative and resulting maps are treated with caution. Three different versions (or recensions) have survived, two of which resemble each other: one dates from the 11th century and is part of a miscellany of works; another is contained in a 17th-century Latin treatise; the third, which has survived in six mediaeval manuscripts, has omissions and spelling variations. All three versions appear to be based on the same lost manuscript: historians have been unable to establish a date for the original compilation. The Tribal Hidage has been used to construct theories about the political organisation of the Anglo-Saxons, and to give an insight into the Mercian state and its neighbours when Mercia held hegemony over them. It has been used to support theories of the origin of the listed tribes and the way in which they were systematically assessed and ruled by others. Some historians have proposed that the Tribal Hidage is not a list of peoples, but of administrative areas.

The hide assessments

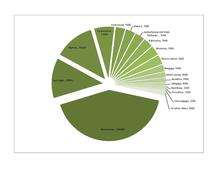

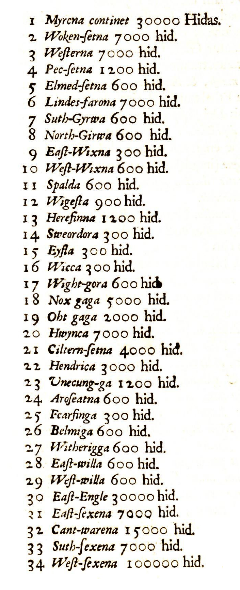

The Tribal Hidage is, according to historian D. P. Kirby, "a list of total assessments in terms of hides for a number of territories south of the Humber, which has been variously dated from the mid-7th to the second half of the 8th century".[1][note 1] Most of the kingdoms of the Heptarchy are included. Mercia, which is assigned 30,000 hides, is at the top at the list,[4] followed by a number of small tribes to the west and north of Mercia, all of which have no more than 7000 hides listed. Other named tribes have even smaller hidages, of between 300 and 1200 hides: of these the Herefinna, Noxgaga, Hendrica and Unecungaga cannot be identified,[5] whilst the others have been tentatively located around the south of England and in the border region between Mercia and East Anglia.[6] Ohtgaga can be heard as Jutegaga and understood as the area settled by Jutes in and near the Meon Valley of Hampshire. The term'-gaga' is a late copyist mistranscription of the Old English '-wara' (people/ men of) the letter forms of 'w' wynn and the long-tailed 'r' being read as 'g'. A number of territories, such as the Hicca, have only been located by means of place-names evidence.[7][8] The list concludes with several other kingdoms from the Heptarchy: the East Angles (who are assessed at 30,000 hides), the East Saxons (7,000 hides), Kent (15,000 hides), the South Saxons (7,000 hides) and Wessex, which is assessed at 100,000 hides.[9]

The round figures of the hidage assessments make it unlikely they were the result of an accurate survey. The methods of assessment used probably differed according to the size of the region.[10] The figures may be of purely symbolic significance, reflecting the status of each tribe at the time it was assessed.[11] The totals given within the text for the figures suggest that the Tribal Hidage was perhaps used as a form of book-keeping.[12] Frank Stenton describes the hidage figures given for the Heptarchy kingdoms as exaggerated and in the instances of Mercia and Wessex, "entirely at variance with other information".[13]

The surviving manuscripts

A manuscript, now lost,[14] was originally used to produce the three recensions of the Tribal Hidage, named A, B and C.[15]

Recension A, which is the earliest and most complete, dates from the 11th century. It is included in a miscellany of works, written in Old English and Latin, with Aelfric's Latin Grammar and his homily De initio creaturæ, written in 1034,[16] and now in the British Library.[note 2] It was written by different scribes,[17] at a date no later than 1032.[18]

Recension B, which resembles Recension A, is contained in a 17th-century Latin treatise, Archaeologus in Modum Glossarii ad rem antiquam posteriorem, written by Henry Spelman in 1626.[18] The tribal names are given in Old English. There are significant differences in spelling between A and B (for instance Spelman's use of the word hidas), indicating that the text he copied was not Recension A, but a different Latin text. According to Peter Featherstone, the highly edited form of the text suggests that Spelman embellished it himself.[10]

Recension C has survived in six Latin documents, all with common omissions and spellings. Four versions, of 13th-century origin, formed part of a collection of legal texts that, according to Featherstone, "may have been intended to act as part of a record of native English custom". The other two are a century older: one is flawed and may have been a scribe's exercise, and the other was part of a set of legal texts.[19]

Origin

Historians disagree on the date for the original compilation of the list. According to Campbell, who notes the plausibility of it being produced during the rise of Mercia, it can probably be dated to the 7th or 8th century.[20] Other historians, such as J. Brownbill, Barbara Yorke, Frank Stenton and Cyril Hart, have written that it originated from Mercia at around this time, but differ on the identity of the Mercian ruler under whom the list was compiled.[21] Wendy Davies and Hayo Vierck have placed the document's origin more precisely at 670-690.[22]

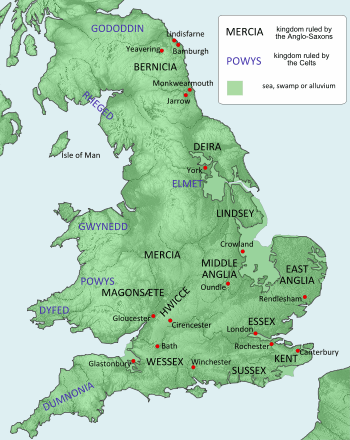

There is near universal agreement that the text originates from Mercia, partly because its kings held extensive power over other territories from the late 7th to the early 9th centuries, but also because the list, headed by Mercia, is almost exclusively of peoples who lived south of the river Humber.[23] Featherstone concludes that the original material, dating from the late 7th century, was used to be included in a late 9th century document and asserts that the Mercian kingdom "was at the centre of the world mapped out by the Tribal Hidage".[15] Frank Stenton wrote that "the Tribal Hidage was almost certainly compiled in Mercia", whilst acknowledging a lack of conclusive evidence.[6]

In contrast to most historians, Nicholas Brooks has suggested that the list is of Northumbrian origin, which would account for the inclusion of Elmet and the absence of the Northumbrian kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia. Mercia would not have been listed, as "an early mediaeval king did not impose tribute upon his own kingdom": it must have been a list produced by another kingdom, perhaps with an altogether different purpose.[24][25]

N. J. Higham has argued that because the original information cannot be dated and the largest Northumbrian kingdoms are not included, it cannot be proved to be a Mercian tribute list. He notes that Elmet, never a province of Mercia, is on the list,[26] and suggests that it was drawn up by Edwin of Northumbria in the 620s,[27] probably originating when a Northumbrian king last exercised imperium over the Southumbrian kingdoms.[28] According to Higham, the values assigned to each people are likely to be specific to the events of 625-626, representing contracts made between Edwin and those who recognised his overlordship, so explaining the rounded nature of the figures: 100,000 hides for the West Saxons was probably the largest number Edwin knew.[29] According to D. P. Kirby, this theory has not been generally accepted as convincing.[30]

Purpose

The purpose of the Tribal Hidage is unknown.[15] Over the years different theories have been suggested for its purpose, linked with a range of dates for its creation.[8]

The Tribal Hidage could have been a tribute list created upon the instructions of an Anglo-Saxon king such as Offa of Mercia, Wulfhere of Mercia or Edwin of Northumbria — but it may have been used for different purposes at various times during its history.[14] Cyril Hart has described it as a tribute list created for Offa, but acknowledges that no proof exists that it was compiled during his rule.[31] Higham notes that the syntax of the text requires that a word implying 'tribute' was omitted from each line, and argues that it was "almost certainly a tribute list".[32] To Higham, the large size of the West Saxon hidation indicates that there was a link between the scale of tribute and any political considerations.[33] James Campbell has argued that if the list served any practical purpose, it implies that tributes were assessed and obtained in an organised way,[20] and notes that, "whatever it is, and whatever it means, it indicates a degree of orderliness, or coherence in the exercise of power...".[34]

Yorke acknowledges that the purpose of the Tribal Hidage is unknown and that it may well not be, as has been commonly argued, an overlord's tribute list. She warns against assuming that the minor peoples (of 7000 hides or less) possessed any "means of defining themselves as a distinct gentes". Among these, the Isle of Wight and the South Gyrwe tribes, tiny in terms of their hidages and geographically isolated from other peoples, were among the few who possessed their own royal dynasties.[8]

P. H. Sawyer argues that the values may have had a symbolic purpose and that they were intended to be an expression of the status of each kingdom and province. To Sawyer, the obscurity of some of the tribal names and the absence from the list of others points to an early date for the original text, which he describes as a "monument to Mercian power". The 100,000 hides assigned to Wessex may have reflected its superior status at a later date and would imply that the Tribal Hidage in its present form was written in Wessex.[35] The very large hidage assessment for Wessex was considered to be an error by the historian J. Brownbill, but Cyril Hart maintains that the value for Wessex is correct and that it was one of several assessments designed to exact the largest possible tribute from Mercia's main rivals.[36]

Historiography

.jpg)

Sir Henry Spelman was the first to publish the Tribal Hidage in his first volume of Glossarium Archaiologicum (1626) and there is also a version of the text in a book written in 1691 by Thomas Gale, but no actual discussion of the Tribal Hidage emerged until 1848, when John Mitchell Kemble's The Saxons in England was published.[31] In 1884, Walter de Gray Birch wrote a paper for the British Archaeological Society, in which he discussed in detail the location of each of the tribes. The term Tribal Hidage was introduced by Frederic William Maitland in 1897, in his book Domesday Book and Beyond.[37] During the following decades, articles were published by William John Corbett (1900), Hector Munro Chadwick (1905) and John Brownbill (1912 and 1925).[37] The most important subsequent accounts of the Tribal Hidage since Corbett, according to Campbell, are by Josiah Cox Russell (1947), Cyril Hart (1971), Wendy Davies and Hayo Vierck (1974) and David Dumville (1989).[38]

Kemble recognised the antiquity of Spelman's document and used historical texts (such as Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum) to assess its date of origin.[39] He proposed locations for each tribe, without attempting to locate each one, and suggested that some Anglo-Saxon peoples were missing from the document.[40] Birch, in his paper An Unpublished Manuscript of some Early Territorial Names in England, announced his discovery of what became known as Recension A, which he suggested was a 10th or 11th century copy of a lost 7th-century manuscript.[41] He methodically compared all the publications and manuscripts of the Tribal Hidage that are available at the time and placed each tribe using both his own theories and the ideas of others, some of which (for instance when he located the Wokensætna in Woking, Surrey) are now discounted.[42] Maitland suspected that the accepted number of acres to each hide needed to be reconsidered to account for the figures in the Tribal Hidage and used his own calculations to conclude that the figures were probably exaggerated.[43] John Brownbill advised against using Latin versions of the document, which he described as error-prone. He determined that the Old English manuscript was written in 1032 and was a copy of an original Mercian manuscript.[44] Chadwick attempted to allocate each tribe to one or more English shires, with the use of key passages from historical texts.[45]

In 1971, Hart attempted a "complete reconstruction of the political geography of Saxon England at the end of the 8th century". Assuming that all the English south of the Humber are listed within the Tribal Hidage, he produced a map that divides southern England into Mercia's provinces and outlying dependencies, using evidence from river boundaries and other topographical features, place-names and historical borders.[46]

Importance for historians

The Tribal Hidage is a valuable record for historians. It is unique in that no similar text has survived: the document is one of a very few to survive out of a great many records that were produced by the administrators of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, a "chance survivor" of many more documents, as Campbell has suggested.[47] Hart has observed that "as a detailed record of historical topography it has no parallel in the whole of western Europe".[31] The Tribal Hidage lists several minor kingdoms and tribes that are not recorded anywhere else[14] and is generally agreed to be the earliest fiscal document that has survived from medieval England.[48]

Historians have used the Tribal Hidage to provide evidence for the political organisation of Anglo-Saxon England and it has been "pressed into service by those seeking to interpret the nature and geography of kingships and of 'peoples' in pre-Viking England", according to N. J. Higham.[48] In particular, the document has been seen as invaluable for providing evidence about the Mercian state and those peoples that were under its rule or influence.[49]

Alex Woolf uses the concentration of tribes with very small hidages between Mercia and East Anglia as part of an argument that there were in existence "large, multi-regional provinces, some of which were surrounded by small, contested territories".[50] Stenton positions the Middle Anglian peoples to the south-east of the Mercians. He suggests that an independent Middle Anglia once existed, seemingly consisting of twenty of the peoples that were listed in the Tribal Hidage. The expansion of Wessex in the tenth century would have caused the obliteration of the Middle Anglia's old divisions,[51] by which time the places listed would have become mere names.[13] Middle Anglia in the 7th century constitutes a model for the development of English administrative units during the period, according to Davies and Vierck, who demonstrate that it was created by Penda of Mercia when he made his son Peada king of the Middle Angles at the time that they were introduced to Christianity.[52]

James Campbell refutes suggestions that the hides given for each tribe were the sum of a system of locally collected assessments and argues that a two-tier system of assessment, one for large areas such as kingdoms and a more accurate one for individual estates, may have existed.[53] He considers the possibility that many of the tribes named in the Tribal Hidage were no more than administrative units and that some names did not originate from a tribe itself but from a place from where the people were governed, eventually coming to signify the district where the tribe itself lived.[54] Barbara Yorke suggests that the -sætan/sæte form of several of the place-names are an indication that they were named after a feature of the local landscape.[55] She also suggests the tribes were dependent administrative units and not independent kingdoms, some of which were created as such after the main kingdoms were stabilized.[56]

The term Tribal Hidage may perhaps have led scholars to underestimate how the names of the tribes were used by Anglo-Saxon administrators for the purpose of labelling local regions;[57] the names could be referring to actual peoples (whose identity was retained after they fell under Mercian domination), or administrative areas that were unconnected with the names of local peoples. Campbell suggests that the truth lies somewhere between these two possibilities.[34] Davies and Vierck believe the smallest of the groups in the Tribal Hidage originated from populations formed into tribes after the departure of the Romans in the fifth century and suggest that these tribes might sometimes have joined forces, until large kingdoms such as Mercia emerged around the beginning of the 7th century.[58] Scott DeGregorio has argued that the Tribal Hidage provides evidence that Anglo-Saxon governments required a system of "detailed assessment" in order to construct great earthworks such as Offa's Dyke.[57]

The kingdom of East Anglia is recorded for the first time in the Tribal Hidage.[59] According to Davies and Vierck, 7th century East Anglia may have consisted of a collection of regional groups, some of which retained their individual identity. Martin Carver agrees with Davies and Vierck when he describes the territory of East Anglia as having unfixed borders, stating that "political authority appears to have primarily invested in people rather than territory".[60]

Notes

- The hide was a unit of assessment that was used to indicate in some way the number of households who lived in an area, but historians have been unable to determine what it measured. It can only start to be described accurately in terms of acres around the time of the Domesday Book (completed in 1086), as at that time one hide was given in eastern England as being equivalent to 120 acres (0.49 km2; 0.19 sq mi), but less than 40 acres (0.16 km2; 0.063 sq mi) in parts of Wessex.[2] The hide was also considered to be the amount needed to sustain a freeman and his family. A man from every five hides was expected to serve in the king's fyrd.[3]

- For a full list of the contents of MS Harley 3271, refer to page 13 of the British Museum's Manuscripts in the Collection, volume 3 (1808).

Harley MS 3271 has been digitized in full and is available online on the British Library's Digitised Manuscripts website at http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Default.aspx, together with a full catalogue description of its contents.

Footnotes

- Kirby, Kings, p. 9.

- Hunter Blair, An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England pp., 267, 269.

- Neal, Defining power in the Mercian Supremacy, p. 14.

- Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 24.

- Brooks, Anglo-Saxon Myths, p. 65.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 296.

- Kirby, Kings, p. 10.

- Yorke, Political and Ethnic Identity, p. 83.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 296-297.

- Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 25.

- Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 28.

- Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 29.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 295.

- Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 23.

- Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 27.

- British Library, Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

- Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, pp. 24-25.

- Neal, Defining power in the Mercian Supremacy, p. 19.

- Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 26.

- Campbell, The Anglo-Saxons, p. 59.

- Neal, Defining Power in the Mercian Supremacy, pp. 20-22.

- Davies and Vierck, The Contexts of Tribal Hidage, p. 227.

- Higham, An English Empire, pp. 74-75.

- Brooks, Anglo-Saxon Myths, p. 62.

- Featherstone, Tribal Hidage, p. 30.

- Higham, An English Empire, pp. 75, 76.

- Higham, An English Empire, p. 50.

- Higham, An English Empire, p. 76.

- Higham, An English Empire, pp. 94-95.

- Kirby, Kings, p. 191, note 45.

- Hart, The Tribal Hidage, p.133.

- Higham, An English Empire, p. 75.

- Higham, An English Empire, p. 94.

- Campbell, The Anglo-Saxons, p. 61.

- Sawyer, From Roman Britain to Norman England, pp. 110-111.

- Hart, The Tribal Hidage, p. 156.

- Hill and Rumble, The Defence of Wessex, p. 183.

- Campbell, The Saxon State, p. 5.

- Kemble, The Saxons in England, pp. 81-82.

- Kemble, The Saxons in England, pp. 83-84.

- Birch, An Unpublished Manuscript of some Early Territorial Names in England, p. 29.

- Birch, An Unpublished Manuscript of some Early Territorial Names in England, p. 34.

- Maitland, Domesday Book and Beyond, pp. 509-510.

- Brownbill, The Tribal Hidage, pp. 625-629.

- Chadwick, England in the Sixth Century, pp. 6-9.

- Hart, The Tribal Hidage, pp. 135-136.

- Campbell, The Anglo-Saxon State, pp. xx-xxi.

- Higham, An English Empire, p. 74.

- Neal, Defining power in the Mercian Supremacy, p. 15.

- Woolf, Social Identity in Early Medieval Britain, p. 99.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon-England, pp. 42-43.

- Hines, The Anglo-Saxons from the Migration Period to the Eighth Century, p. 358.

- Campbell, The Anglo-Saxon State, p. 6.

- Campbell, The Anglo-Saxon State, p. 5.

- Yorke, Political and Ethnic Identity, p. 84.

- Yorke, Political and Ethnic Identity, p. 86.

- DeGregorio, The Cambridge Companion to Bede, pp. 30-31.

- Baxter et al, Early Medieval Studies in Memory of Patrick Wormald, pp. 54, 91.

- Carver, The Age of Sutton Hoo, p. 3.

- Carver, The Age of Sutton Hoo, pp. 6, 7.

Sources

Early printed texts and commentaries

- Birch, Walter de Gray (1884). "An Unpublished Manuscript of some Early Territorial Names in England". Journal of the British Archaeological Society. 1. 40: 28–46. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Brownbill, J. (October 1912). "The Tribal Hidage". The English Historical Review. 27: 625–648. doi:10.1093/ehr/xxvii.cviii.625. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Chadwick, H. M. (1907). "1 England in the Sixth Century". The Origin of the English Nation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–10. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- Gale, Thomas (1691). Historiae Britannicae, Saxonicae, Anglo-Danicae Scriptores XV, volume 3 (in Latin). Oxford. p. 748. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- Kemble, John Mitchell (1876). The Saxons in England, volume 1. London: Bernard Quaritch. pp. 81–84.

- Maitland, Frederic William (1907). Domesday Book and Beyond: Three Essays in the Early History of England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 506–509.

- Riley, Henry; Carpenter, John (1860). "Extracts from the Cottonian Portians of Liber Custumarum and Liber Legum Regum Antiquorum which have not previously appeared in the Government publications". Chronicles and memorials of Great Britain and Ireland during the Middle Ages (in Latin and English). London: Great Britain Public Record Office. pp. 626–627. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- Spelman, Henry (1626). Glossarium Archaiologicum (in Latin) (1687 ed.). London. pp. 291–292. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

Modern sources

- Baxter, Stephen David; Karkov, Catherine E.; Nelson, Janet L.; et al. (eds.). Early Medieval Studies in Memory of Patrick Wormald. Farnham (UK), Burlington (USA): Ashgate.

- Brooks, Nicholas (2000). Anglo-Saxon Myths: State and Church 400-1066. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 1-85285-154-6.

- Campbell, James, ed. (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-014395-5.

- Campbell, James (2000). The Anglo-Saxon State. London, New York: Hambledon and London. ISBN 1-85285-176-7.

- Carver, M. O. H., ed. (1992). The Age of Sutton Hoo: the Seventh Century in North-western Europe. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-851-15361-5.

- Davies, Wendy; Vierck, Hayo (1974). "The Contexts of Tribal Hidage: Social Aggregates and Settlement Patterns". Frühmittelalterliche Studien. 8. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024207-2.

- DeGregorio, Scott, ed. (2010). The Cambridge Companion to Bede. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-73073-0.

- Featherstone, Peter (2001). "The Tribal Hidage and the Ealdormen of Mercia". In Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-8264-7765-8.

- Hart, Cyril (1971). "Tribal Hidage". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 5th series. 21: 133–157. doi:10.2307/3678924.

- Higham, N. J. (1995). An English Empire: Bede and the Early Anglo-Saxon Kings. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4424-3.

- Hill, David; Rumble, Alexander R. (1996). The Defence of Wessex: the Burghal Hidage and Anglo-Saxon Fortifications. Manchester, New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3218-0.

- Hines, John, ed. (1997). The Anglo-Saxons from the Migration Period to the Eighth Century. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-034-5.

- Hunter Blair, Peter (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29219-0.

- Kirby, D.P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-4152-4211-8.

- Neal, James R. (May 2008). Defining power in the Mercian Supremacy: An examination of the dynamics of power in the kingdom of the borderers. (Submitted thesis). Reno: University of Nevada. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- Sawyer, P. H. (1978). From Roman Britain to Norman England. London: Methuen.

- Stenton, Sir Frank (1988). Anglo-Saxon England. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821716-1.

- Woolf, Alex (2000). "Community, Identity and Kingship in Early England". In Frazer, William O.; Tyrrell Andrew (eds.). Social Identity in Early Medieval Britain. London and New York: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-0084-9.

- Yorke, Barbara (2000). "Political and Ethnic Identity: A Case Study of Anglo-Saxon Practice". In Frazer, William O.; Tyrrell Andrew (eds.). Social Identity in Early Medieval Britain. London and New York: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-0084-9.

Further reading

For a comprehensive bibliography of the Tribal Hidage, refer to Hill. D and Rumble, A. R., The Defence of Wessex, Appendix III - The Tribal Hidage: an annotated bibliography.

- British Library. "Detailed record for Harley 3271". Catalogue of Illuminated Scripts. Retrieved 17 November 2011. There is a link to an image of the mediaeval manuscript.

- Blair, John (1999). "Tribal Hidage". In Lapidge, Michael; et al. (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Dumville, David (1989). "The Tribal Hidage: an introduction to its texts and their history". In Bassett, S. (ed.). Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Leicester: Leicester University Press. pp. 225–30. ISBN 0-7185-1317-7.