Royal supporters of England

The royal supporters of England refer to the heraldic supporter creatures appearing on each side of the royal arms of England. The royal supporters of the monarchs of England displayed a variety, or even a menagerie, of real and imaginary heraldic beasts, either side of their royal arms of sovereignty, including lion, leopard, panther and tiger, antelope and hart, greyhound, boar and bull, falcon, cock, eagle and swan, red and gold dragons, as well as the current unicorn.[1]

Heraldic supporters of the monarchs of England

| Monarch (Reign) | Supporters[2] | Details | Coat of arms |

|---|---|---|---|

(1327–1399) | |||

King Edward III (1327–1377) |

|

King Edward III was supposed to have used on the dexter side a Lion guardant Or, crowned of the last; and on the sinister, by a Falcon Argent, membered Or. However, there is no conclusive evidence to assume that a definitive set of heraldic supporters were in use so early at this period.[4] |

_(Attributed).svg.png) lion and falcon |

.jpg) King Richard II (1377–1399) |

|

King Richard's arms appear on the north front of Westminster Hall. On the base of the escutcheon rests his royal badge of the white hart; which is collared and chained. This device is derived from the personal badge of his mother Joan of Kent. The same device was also used by her son, from her first husband; Thomas Holland, 1st Earl of Kent. In this same decoration the escutcheon is surrounded by two angels, however these the character of pious emblems, rather than heraldic figures.[5] Another example lies in St Olave's Church, Hart Street, depicts the arms of the monarch impaled with those of his patron saint; Edward the Confessor. Here is escutcheon is supported by two Harts Argent, collared and chained Or.[6] |

.svg.png) two harts |

(1399–1413) | |||

.jpg) King Henry IV (1399–1413) |

|

King Henry IV was supposed to have his escutcheon supported on the dexter by an antelope Argent, ducally collared, lines, and armed Or; and on the sinister, by a swan Argent. However no remaining monuments have been found that supports conclusive proof that these devices were used as such. The device of the swan is derived from the Bohun swan of the family of de Bohun, a descendant of which, Mary de Bohun, was Henry's first wife.[7] It is likely that these may have been used only as badges and not as supporters at all. (Page 89)[8] The heraldic antelope appears to have also been derived from the Bohun family.[9][10] |

.svg.png) lion and antelope |

King Henry V (1413–1422) |

|

King Henry V as king bore on the dexter side a lion guardant Or, on the sinister an antelope Argent.[11] |

.svg.png) lion and antelope |

.jpg) King Henry VI (1422–1461) |

|

King Henry VI's arms are supported by two antelopes, this depiction appears on the ceiling of the southern aisle of St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle; and on the upper part of the inner gateway of Eton College.[12] Possibly the first English king to systematically used supporters, in their arms, previously they were used ornamentally rather than as part of the heraldic science. The heraldic antelopes are described thus; two heraldic antelopes Argent, armed and tufted Or. [13] |

.svg.png) two antelopes |

(1413–1485) | |||

King Edward IV (1461–1483) |

|

King Edward IV's arms contained the white lion, which had been used as supporters by the Mortimers, Earls of March. When he himself was Earl of March, his arms were indeed supported by two white lions; lions rampant guardant Argent, their tails passing between their legs and over their backs.[14][15] A black bull, with horns, hoofs Or, is sometimes incorporated as a supporter interchangeably with other creature either on the dexter or sinister side. The bull was a device of Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, the second son of Edward III. The House of York were descended through him by Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York and his mother Anne de Mortimer.[16] The white hart was evidently derived from the arms of Richard II, who in 1387 declared Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, Edward's maternal great-grandfather, his lawful heir to the crown.[14] |

.svg.png) two lions |

King Edward V (1483) |

|

The short-lived monarch shares his supporters with his father: the white lion and the white hart.[17] A painting of the king's arms is found in St George's Chapel, beside the tomb of Oliver King, Bishop of Exeter. It shows dexter a lion argent and sinister a hind argent.[18] |

.svg.png) lion and hart |

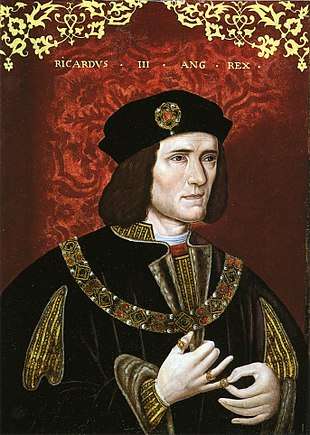

King Richard III (1483–1485) |

|

King Richard III used most prominently two white boars as his supporters. Even before his ascension to the throne the white boar was used as a personal badge, also in his service was a pursuivant called 'Blanc Sanglier'. The satire of William Collingbourne, referring to Richard as a 'hogge' is well known.[19]The boars are described as; A boar rampant argent, armed and bristled Or.[20] |

.svg.png) two boars |

(1485–1606) | |||

King Henry VII (1485–1509) |

|

King Henry VII used as his supporters a red dragon and a white greyhound. The red dragon is traditionally the symbol of Cadwaladr, King of Gwynedd. Henry VII claims his descent from the Welsh leader, and was fond of the myth surrounding his reign. However the dragon itself have long been borne by various English kings in their standard; such as Henry III, Edward I and Edward III.[21] The dragon is described as; a dragon Gules garnished and armed Or.[22] The white greyhound have been used as a device by the House of York, it was assumed as a supporter by Henry in right of his wife, who derived it from her grandmother's family of Neville.[23] At other times the greyhound have been attributed to the House of Beaufort, the family of Henry's mother; Margaret Beaufort, rather than York.[24]The greyhound is described as; a greyhound Argent collared Gules.[25] |

.svg.png) dragon and greyhound |

King Henry VIII (1509–1547) |

|

During the first half of his reign, King Henry VIII used the same supporters as his father, this was depicted on many manuscripts which belonged to him. Afterwards he began to use a crowned lion of England on the dexter side and the red dragon on the sinister side.[26] The lion is described as; A lion guardant Or, imperially crowned proper.[27] |

.svg.png) lion and dragon |

King Edward VI (1547–1553) |

|

King Edward VI used the same supporters, without change, from those used by his father on the latter half of his reign.[28] |

.svg.png) lion and dragon |

Queen Mary I (1553–1558) |

|

Queen Mary I used as her supporters; on the dexter an eagle Sable, with wings endorsed; and on the sinister a crowned lion of England. The eagle was the supporter of her husband King Philip II of Spain.[29] |

.svg.png) eagle and lion |

Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603) |

|

Queen Elizabeth I used the supporters of her father, a crowned lion and a dragon. However, sometimes the red dragon is substituted with a golden one.[30] |

.svg.png) lion and dragon |

(1603–1649) | |||

King James I (1603–1625) |

|

When King James VI of Scotland inherited the English throne in 1603 and became King James I of England, he exchanged the red dragon with the Scottish unicorn of his ancestors.[31] The royal arms of Scotland have been supported by two unicorns since the reign of King James V.[32] The unicorn is blazoned as: a unicorn Argent, armed, unguled, craned, and gorged with a royal coronet Or, having a chain affixed thereto and reflexed over the back all Or.[33] However to preserve a distinct identity for both nations, the king allowed for the use of two coats of arms; one for England and another for Scotland. In Scotland the position of the supporters are switched with the unicorn in the dexter and the lion in the sinister. The unicorn is also imperially crowned, similarly to the lion.[34] |

.svg.png) lion and unicorn |

.jpg) King Charles I (1625–1649) |

|

King Charles I uses the same supporters as those of his father, the crowned lion and unicorn.[35] Blazoned as; dexter a lion rampant guardant Or imperially crowned, sinister a unicorn Argent armed, crined and unguled Proper, gorged with a coronet Or composed of crosses patée and fleurs de lys a chain affixed thereto passing between the forelegs and reflexed over the back also Or.[36] |

.svg.png) lion and unicorn |

(1653–1659) | |||

Oliver Cromwell (1653–1658) |

|

During the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell a coat of arms was created for use in the Great Seal. This coat of arms featured; Dexter, a lion guardant Or, crowned with the imperial crown Proper, Sinister, a dragon gules. Perhaps it was thought that the arms and motto of the Royal family was too personal and must be dropped. The supporters and crest, however was less personal but more national in character and was retained. The substitution of the Tudor dragon in favour of the unicorn demonstrates a clear rejection of the Stuarts and their symbols.[37] |

.svg.png) lion and dragon |

Richard Cromwell (1658–1659) |

|

The younger Cromwell retained the arms of his father for the eight months he held the office, until his rule was terminated by the Restoration in May 1660.[37] |

.svg.png) lion and dragon |

(1660–1707) | |||

.jpg) King Charles II (1660–1685) |

|

King Charles II uses; dexter a lion rampant guardant Or imperially crowned, sinister a unicorn Argent armed, crined and unguled Proper, gorged with a coronet Or composed of crosses patée and fleurs de lys a chain affixed thereto passing between the forelegs and reflexed over the back also Or.[38] |

.svg.png) lion and unicorn |

King James II (1685–1688) |

|

King James II uses; dexter a lion rampant guardant Or imperially crowned, sinister a unicorn Argent armed, crined and unguled Proper, gorged with a coronet Or composed of crosses patée and fleurs de lys a chain affixed thereto passing between the forelegs and reflexed over the back also Or.[39] |

.svg.png) lion and unicorn |

King William III and Queen Mary II (1689–1694) |

|

King William III and Queen Mary uses; dexter a lion rampant guardant Or imperially crowned, sinister a unicorn Argent armed, crined and unguled Proper, gorged with a coronet Or composed of crosses patée and fleurs de lys a chain affixed thereto passing between the forelegs and reflexed over the back also Or.[40] |

.svg.png) lion and unicorn |

King William III (1689–1702) |

|

King William III uses; dexter a lion rampant guardant Or imperially crowned, sinister a unicorn Argent armed, crined and unguled Proper, gorged with a coronet Or composed of crosses patée and fleurs de lys a chain affixed thereto passing between the forelegs and reflexed over the back also Or.[41] |

.svg.png) lion and unicorn |

Queen Anne (1702–1707) |

|

Queen Anne uses; dexter a lion rampant guardant Or imperially crowned, sinister a unicorn Argent armed, crined and unguled Proper, gorged with a coronet Or composed of crosses patée and fleurs de lys a chain affixed thereto passing between the forelegs and reflexed over the back also Or.[41] |

.svg.png) lion and unicorn |

References

- Citations

- The Art of Heraldry: An Encyclopædia of Armory. A.C. Fox-Davies. (ch XXX, p300). (1986). ISBN 0-906223-34-2.

- Charles Hasler, The Royal Arms, pp.3–11. ISBN 0-904041-20-4

- The Penny Magazine. 18 April 1835

- Willement 1821, p. 16.

- Willement 1821, p. 20.

- Willement 1821, p. 21.

- Willement 1821, p. 28.

- Pinches 1974, p. 89.

- Willement 1821, p. 29.

- Pinches 1974, p. 90.

- Willement 1821, p. 33.

- Willement 1821, p. 35.

- Pinches 1974, p. 97.

- Willement 1821, p. 46.

- Pinches 1974, p. 113.

- Willement 1821, p. 45.

- Willement 1821, p. 49.

- Pinches 1974, p. 121.

- Willement 1821, p. 50.

- Pinches 1974, p. 122.

- Willement 1821, pp. 58–59.

- Pinches p. 133

- Willement 1821, p. 59.

- Willement 1821, p. 60.

- Pinches 1974, p. 133.

- Willement 1821, pp. 64–65.

- Pinches 1974, p. 140.

- Willement 1821, p. 76.

- Willement 1821, p. 78.

- Pinches 1974, p. 154.

- Willement pp. 88–89

- Pinches 1974, p. 159.

- Pinches 1974, p. 160.

- Pinches 1974, p. 169.

- Willement 1821, p. 92.

- Pinches 1974, p. 174.

- Pinches 1974, p. 179.

- Pinches 1974, p. 181.

- Pinches 1974, p. 187.

- Brooke-Little 1978, p. 214.

- Brooke-Little 1978.

- Bibliography

- Aveling, S. T (1890). Heraldry: Ancient and Modern including Boutell's Heraldry. London: Frederick Warne and Co. ISBN 0548122040.

- Boutell, Charles (1863). A Manual of Heraldry, Historical and Popular. London: Windsor And Newton. ISBN 1146289545.

- Brooke-Little, J.P., FSA (1978) [1950], Boutell's Heraldry (Revised ed.), London: Frederick Warne LTD, ISBN 0-7232-2096-4

- Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974), The Royal Heraldry of England, Heraldry Today, Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press, ISBN 0-900455-25-X

- Willement, Thomas (1821), Regal Heraldry, London: W. Wilson

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal coats of arms of England. |

- Royal Standards of England

- Royal Badges of England

- Royal Arms of England

- Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom

- Heraldry

.svg.png)