Lake Ontario

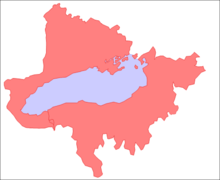

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is surrounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the American state of New York, whose water boundaries meet in the middle of the lake. Ontario, Canada's most populous province, was named for the lake.

| Lake Ontario | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Lake Ontario shoreline in Mississauga, Ontario | |

| |

| Location | North America |

| Group | Great Lakes |

| Coordinates | 43.7°N 77.9°W |

| Lake type | Freshwater |

| Etymology | Ontarí:io, a Huron (Wyandot) word meaning "great lake" |

| Primary inflows | Niagara River |

| Primary outflows | St. Lawrence River |

| Catchment area | 24,720 sq mi (64,000 km2)[5] |

| Basin countries | United States Canada |

| Max. length | 193 mi (311 km)[6] |

| Max. width | 53 mi (85 km)[6] |

| Surface area | 7,340 sq mi (19,000 km2)[5] |

| Average depth | 283 ft (86 m)[6][7] |

| Max. depth | 802 ft (244 m)[6][7] |

| Water volume | 393 cu mi (1,640 km3)[6] |

| Residence time | 6 years |

| Shore length1 | 634 mi (1,020 km) plus 78 mi (126 km) for islands[8] |

| Surface elevation | 243 ft (74 m)[6] |

| Settlements | Toronto, Ontario Hamilton, Ontario Rochester, New York |

| References | [7] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

The Canadian cities of Toronto, Kingston, and Hamilton are located on the lake's northern and western shorelines, while the American city of Rochester is located on the south shore. In the Huron language, the name Ontarí'io means "great lake". Its primary inlet is the Niagara River from Lake Erie. The last in the Great Lakes chain, Lake Ontario serves as the outlet to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. It is the only Great Lake not to border the state of Michigan.

Geography

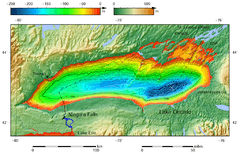

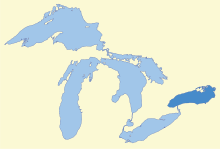

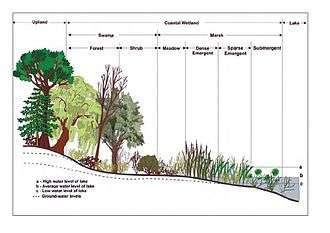

Lake Ontario is the easternmost of the Great Lakes and the smallest in surface area (7,340 sq mi, 18,960 km2),[5] although it exceeds Lake Erie in volume (393 cu mi, 1,639 km3). It is the 13th largest lake in the world. When its islands are included, the lake's shoreline is 712 miles (1,146 km) long. As the last lake in the Great Lakes' hydrologic chain, Lake Ontario has the lowest mean surface elevation of the lakes at 243 feet (74 m)[6] above sea level; 326 feet (99 m) lower than its neighbor upstream. Its maximum length is 193 statute miles (311 kilometres; 168 nautical miles) and its maximum width is 53 statute miles (85 km; 46 nmi).[6] The lake's average depth is 47 fathoms 1 foot (283 ft; 86 m), with a maximum depth of 133 fathoms 4 feet (802 ft; 244 m).[6][7] The lake's primary source is the Niagara River, draining Lake Erie, with the St. Lawrence River serving as the outlet. The drainage basin covers 24,720 square miles (64,030 km2).[5][9] As with all the Great Lakes, water levels change both within the year (owing to seasonal changes in water input) and among years (owing to longer-term trends in precipitation). These water level fluctuations are an integral part of lake ecology, and produce and maintain extensive wetlands.[10][11] The lake also has an important freshwater fishery, although it has been negatively affected by factors including over-fishing, water pollution and invasive species.[12]

Baymouth bars built by prevailing winds and currents have created a significant number of lagoons and sheltered harbors, mostly near (but not limited to) Prince Edward County, Ontario and the easternmost shores. Perhaps the best-known example is Toronto Bay, chosen as the site of the Upper Canada (Ontario) capital for its strategic harbour. Other prominent examples include Hamilton Harbour, Irondequoit Bay, Presqu'ile Bay, and Sodus Bay. The bars themselves are the sites of long beaches, such as Sandbanks Provincial Park and Sandy Island Beach State Park. These sand bars are often associated with large wetlands, which support large numbers of plant and animal species, as well as providing important rest areas for migratory birds.[13][14] Presqu'ile, on the north shore of Lake Ontario, is particularly significant in this regard. One unique feature of the lake is the Z-shaped Bay of Quinte which separates Prince Edward County from the Ontario mainland, save for a 2-mile (3.2 km) isthmus near Trenton; this feature also supports many wetlands and aquatic plants, as well as associated fisheries.

Major rivers draining into Lake Ontario include the Niagara River, Don River, Humber River, Trent River, Cataraqui River, Genesee River, Oswego River, Black River, Little Salmon River, and the Salmon River.

Geology

The lake basin was carved out of soft, weak Silurian-age rocks by the Wisconsin ice sheet during the last ice age. The action of the ice occurred along the pre-glacial Ontarian River valley which had approximately the same orientation as today's basin. Material that was pushed southward by the ice sheet left landforms such as drumlins, kames, and moraines, both on the modern land surface and the lake bottom,[15] reorganizing the region's entire drainage system. As the ice sheet retreated toward the north, it still dammed the St. Lawrence valley outlet, so the lake surface was at a higher level. This stage is known as Lake Iroquois. During that time the lake drained through present-day Syracuse, New York into the Mohawk River, thence to the Hudson River and the Atlantic. The shoreline created during this stage can be easily recognized by the (now dry) beaches and wave-cut hills 10 to 25 miles (15 to 40 km) from the present shoreline.

When the ice finally receded from the St. Lawrence valley, the outlet was below sea level, and for a short time the lake became a bay of the Atlantic Ocean, in association with the Champlain Sea. Gradually the land rebounded from the release of the weight of about 6,500 feet (2,000 m) of ice that had been stacked on it. It is still rebounding about 12 inches (30 cm) per century in the St. Lawrence area. Since the ice receded from the area last, the most rapid rebound still occurs there. This means the lake bed is gradually tilting southward, inundating the south shore and turning river valleys into bays. Both north and south shores experience shoreline erosion, but the tilting amplifies this effect on the south shore, causing loss to property owners.

History

The name Ontario is derived from the Huron word Ontarí'io, which means "great lake". The lake was a border between the Huron people and the Iroquois Confederacy in the pre-Columbian era. In the 1600s, the Iroquois drove out the Huron from southern Ontario and settled the northern shores of Lake Ontario. When the Iroquois withdrew and the Anishnabeg / Ojibwa / Mississaugas moved in from the north to southern Ontario, they retained the Iroquois name.[16]

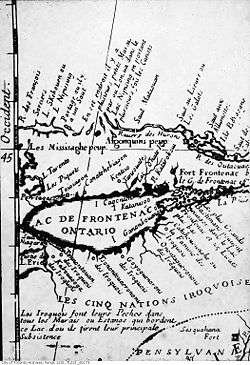

It is believed the first European to reach the lake was Étienne Brûlé in 1615. As was their practice, the French explorers introduced other names for the lake. In 1632 and 1656, the lake was referred to as Lac de St. Louis or Lake St. Louis by Samuel de Champlain and cartographer Nicolas Sanson respectively (likely for Louis XIV of France)[17] In 1660 Jesuit historian Francis Creuxius coined the name Lacus Ontarius. In a map drawn in the Relation des Jésuites (1662–1663), the lake bears the legend "Lac Ontario ou des Iroquois" with the name "Ondiara" in smaller type. A French map produced in 1712 (currently in the Canadian Museum of History[18]), created by military engineer Jean-Baptiste de Couagne, identified Lake Ontario as "Lac Frontenac" named after Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac et de Palluau. He was a French soldier, courtier, and Governor General of New France from 1672 to 1682 and from 1689 to his death in 1698.

Artifacts which are believed to be of Norse origin have been found in the area of Sodus Bay, indicating the possibility of trading by the indigenous peoples with Norse explorers on the east coast of North America.[19]

A series of trading posts were established by both the British and French, such as Fort Frontenac (Kingston) in 1673, Fort Oswego in 1722, Fort Rouillé (Toronto) in 1750. After the French and Indian War, all forts around the lake were under British control. The United States did not take possession of forts on present-day American territory until the signing of the Jay Treaty in 1794. Permanent, non-military European settlement began during the American Revolution. As the easternmost and nearest lake to the Atlantic seaboard of Canada and the United States, population centres here are among the oldest in the Great Lakes basin, with Kingston, Ontario, formerly the capital of Canada, dating to the 1670s (Fort Frontenac). The lake became a hub of commercial activity following the War of 1812 with canal building on both sides of the border and heavy travel by lake steamers. Steamer activity peaked in the mid-19th century before competition from railway lines.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a type of scow known as a stone hooker was in operation on the north-west shore, particularly around Port Credit and Bronte. Stonehooking was the practice of raking flat fragments of Dundas shale from the shallow lake floor of the area for use in construction, particularly in the growing city of Toronto.[20]

Ecology and environmental concerns

The Great Lakes watershed is a region of high biodiversity, and Lake Ontario is important for its diversity of birds, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and plants. Many of these special species are associated with shorelines, particularly sand dunes, lagoons, and wetlands. The importance of wetlands to the lake has been appreciated, and many of the larger wetlands have protected status. However, these wetlands are changing in part because the natural water level fluctuations have been reduced. Many wetland plants are dependent upon low water levels to reproduce.[21] When water levels are stabilized, the area and diversity of the marsh is reduced. This is particularly true of meadow marsh (also known as wet meadow wetlands); for example, in Eel Bay near Alexandria Bay, regulation of lake levels has resulted in large losses of wet meadow.[22] Often this is accompanied by the invasion of cattails, which displace many of the native plant species and reduce plant diversity. Eutrophication may accelerate this process by providing nitrogen and phosphorus for the more rapid growth of competitively dominant plants.[23] Similar effects are occurring on the north shore, in wetlands such as Presqu'ile, which have interdunal wetlands called pannes, with high plant diversity and many unusual plant species.[24]

Most of the forests around the lake are deciduous forests dominated by trees including maple, oak, beech, ash and basswood. These are classified as part of the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone by Environment Canada, or as the Eastern Great Lakes and Hudson Lowlands by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, or as the Great Lakes Ecoregion by The Nature Conservancy.[25] Deforestation in the vicinity of the lake has had many negative impacts,[26] including loss of forest birds, extinction of native salmon, and increased amounts of sediment flowing into the lake. In some areas more than 90 percent of the forest cover has been removed and replaced by agriculture. Certain tree species, such as hemlock, have also been particularly depleted by past logging activity.[27] Guidelines for restoration stress the importance of maintaining and restoring forest cover, particularly along streams and wetlands.[28][29]

The open water is less-affected by shoreline features, such as wetlands, and more affected by nutrient levels that control the production of algae. Algae are the basis of the open water food web, and the source of primary production that ends up as Lake Trout and Walleye at the top of the open water food web.

Like the other Great Lakes, Lake Ontario used to have an important commercial fishery. It has been largely destroyed, mostly by over-fishing. Consider the Lake Sturgeon as but one example. Lake sturgeon are huge fish—they can grow up to three meters long and exceed 190 kg in weight. The females mature slowly and require decades to reach sexual maturity. It was once an abundant species in Lake Ontario. "In 1860, this species, taken on incidental catches of other fishes, was killed and dumped back in the lake, piled up on shore to dry and be burned, fed to pigs, or dug into the earth as fertilizer."[30] It was even stacked like cordwood and used to fuel steamboats. Once its value was realized, "They were taken by every available means from spearing and jigging to set lines of baited or unbaited hooks laid on the bottom to trapnets, poundnets and gillnets."[30] Over 5 million pounds were taken from adjoining Lake Erie in a single year. The fishery collapsed, largely by 1900. They have never recovered. Like most sturgeons, the lake sturgeon is rare now, and is protected in many areas. Populations in the Oswego River are being actively managed for recovery.

This food web has been damaged not only by over-fishing, and changes in nutrient levels, but also by other types of pollution from industrial chemicals, agricultural fertilizers, untreated sewage, phosphates from laundry detergents, and pesticides. Some pollutant chemicals that have been found in the lake include DDT, benzo[a]pyrene and other pesticides; PCBs, aramite, chromium, lead, mirex, mercury, and carbon tetrachloride. The International Joint Commission has identified areas where pollution is particularly intense (point sources) and mapped them as Areas of Concern. A Remedial Action Plan has been developed for each area. Some Lake Ontario areas of concern include the Oswego River and Rochester Embayment on the American side, and Hamilton Harbour and Toronto on the Canadian side.

By the 1960s and 1970s, the increased pollution caused frequent algal blooms to occur in the summer.[12] These blooms killed large numbers of fish, and left decomposing piles of filamentous algae and dead fish along the shores.[31] At times the blooms became so thick waves could not break. Fish eating birds such as osprey, bald eagle and cormorant were being poisoned by contaminated fish. Since the 1960s and 1970s, environmental concerns have forced a cleanup of industrial and municipal wastes. Cleanup has been accomplished through better treatment plants, tighter environmental regulations, deindustrialization and increased public awareness. Today, Lake Ontario has recovered some of its pristine quality; for example, walleye, a fish species considered as a marker of clean water, are now found. However, regional airshed pollution remains a concern. The lake has also become an important sport fishery, although with introduced species (Coho and Chinook salmon) rather than the native species. Bald eagle and osprey populations are also beginning to recover.

Invasive species are a problem for Lake Ontario, particularly lamprey and zebra mussels. Lamprey are being controlled by poisoning in the juvenile stage in the streams where they breed. Zebra mussels in particular are difficult to control, and pose major challenges for the lake and its waterways.

Climate

The lake has a natural seiche rhythm of eleven minutes. The seiche effect normally is only about 3⁄4 inches (2 cm) but can be greatly amplified by earth movement, winds, and atmospheric pressure changes.

Because of its great depth, the lake as a whole never freezes in winter, but an ice sheet covering between 10% and 90% of the lake area typically develops, depending on the severity of the winter. Ice sheets typically form along the shoreline and in slack water bays, where the lake is not as deep. During the winters of 1877 and 1878, the ice sheet coverage was up to 95–100% in most of the lake. In the winter of 1812, the ice cover was stable enough the American naval commander stationed at Sackets Harbor feared a British attack from Kingston, over the ice.

When the cold winds of winter pass over the warmer water of the lake, they pick up moisture and drop it as lake effect snow. Since the prevailing winter winds are from the northwest, the southern and southeastern shoreline of the lake is referred to as the snowbelt. In some winters the area between Oswego and Pulaski may receive twenty or more feet (600 cm) of snowfall.

Also impacted by lake-effect snow is the Tug Hill Plateau, an area of elevated land about 20 miles (32 km) east of Lake Ontario, creating ideal conditions for lake-effect snowfall. The "Hill", as it is often referred to, typically receives more snow than any other region in the eastern United States. As a result, Tug Hill is a popular location for winter enthusiasts, such as snow-mobilers and cross-country skiers. Lake-effect snow often extends inland as far as Syracuse, with that city often recording the most winter snowfall accumulation of any large city in the United States. Other cities in the world receive more snow annually, such as Quebec City, which averages 135 inches (340 cm), and Sapporo, Japan, which receives 250 inches (640 cm) each year and is often regarded as the snowiest city in the world. Foggy conditions (particularly in fall) can be created by thermal contrasts and can be an impediment for recreational boaters. In a normal winter, Lake Ontario will be at most one quarter ice-covered, in a mild winter almost completely unfrozen. Lake Ontario has completely frozen over on five recorded occasions: from about January 20 to about March 20, 1830;[32] in 1874;[33] in 1893;[33] in 1912;[33] and in February 1934.[33]

Lake breezes in spring tend to retard fruit bloom until the frost danger is past, and in the autumn delay the onset of fall frost, particularly on the south shore. Cool onshore winds also retard early bloom of plants and flowers until later in the spring season, protecting them from possible frost damage. Such microclimatic effects have enabled tender fruit production in a continental climate, with the southwest shore supporting a major fruit-growing area. Apples, cherries, pears, plums, and peaches are grown in many commercial orchards around Rochester. Between Stoney Creek and Niagara-on-the-Lake on the Niagara Peninsula is a major fruit-growing and wine-making area. The wine-growing region extends over the international border into Niagara and Orleans counties. Apple varieties that tolerate a more extreme climate are grown on the lake's north shore, around Cobourg.

Settlements

A large conurbation called the Golden Horseshoe occupies the lake's westernmost shores, anchored by the cities of Toronto and Hamilton. Ports on the Canadian side include St. Catharines, Oshawa, Cobourg and Kingston, near the St. Lawrence River outlet. Close to 9 million people or over a quarter of Canada's population lives within the watershed of Lake Ontario. The American shore is largely rural, with the exception of Rochester and the much smaller ports at Oswego and Sackets Harbor. The city of Syracuse is 40 miles (64 km) inland, connected to the lake by the New York State Canal System. Over 2 million people live in Lake Ontario's American watershed.

A high-speed passenger/vehicle ferry, the Spirit of Ontario I, operated between Toronto and Rochester from June 17, 2004, to January 10, 2006, when the service was cancelled. The Crystal Lynn II, out of Irondequoit, New York, has been operating between Irondequoit Bay and Henderson, New York since May 2000, operated by Capt. Bob Tein.

- Ontario, Canada

- Toronto

- Mississauga

- Hamilton

- Burlington

- Oshawa

- Kingston

- Whitby

- Stoney Creek

- Grimsby

- Oakville

- St. Catharines

- Port Hope

- Cobourg

- Brighton

- Pickering

- Ajax

- Bowmanville

- Belleville

- Trenton

- Niagara-on-the-Lake

- New York, United States

Ocean and lake navigation

The Great Lakes Waterway connects the lake sidestream to the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence Seaway, and upstream to the other rivers in the chain via the Welland Canal and to Lake Erie. The Trent-Severn Waterway for pleasure boats connects Lake Ontario at the Bay of Quinte to Georgian Bay (Lake Huron), via Lake Simcoe. The Oswego Canal connects the lake at Oswego to the New York State Canal System, with outlets to the Hudson River, Lake Erie, and Lake Champlain.

The Rideau Canal, also for pleasure boats, connects Lake Ontario at Kingston to the Ottawa River in downtown Ottawa, Ontario.

Lighthouses

- Beach Canal Lighthouse

- Braddock Point Light

- Charlotte-Genesee Lighthouse

- Gibraltar Point Lighthouse

- Oswego Harbor West Pierhead Light

- Presqu'ile Lighthouse

- Selkirk Lighthouse

- Sodus Point Light

- Stony Point Light

- Thirty Mile Point Light

Islands

Nearly all of Lake Ontario's islands are on the eastern and north-eastern shores, between the Prince Edward County headland and the lake's outlet at Kingston. The Toronto Islands on the north-western shore are the remnants of a sand spit formed by coastal erosion, whereas the mostly larger eastern islands are underlain by the basement rock found throughout the region. The largest island is Wolfe Island, at the east end of the lake. It is accessible by ferry from both Canada and the U.S.

- Toronto Islands

- Wolfe Island

- Association Island

- Galloo Island – and nearby Little Galloo Island, Calf Island, and Stony Island

- Amherst Island

- Simcoe Island

- Garden Island

- Grenadier Island

- Waupoos Island

- Nicholson Island

- Big Island

Other topics

The Great Lakes Circle Tour and Seaway Trail are designated scenic road systems connecting all of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River.[34] As the Seaway Trail is posted on the U.S. side only, Lake Ontario is the only of the five Great Lakes to have no posted bi-national circle tour.

In the 1800s, there were reports of an alleged creature, similar to the so-called Loch Ness Monster, being sighted in the lake. The creature is described as large with a long neck, green in colour, and generally causes a break in the surface waves.[35][36][37]

Swims across the lake

As of 2012, nearly 50 people have successfully swum across the lake.[38] The first person who accomplished the feat was Marilyn Bell, who did it in 1954 at the age of 16. Toronto's Marilyn Bell Park is named in her honour. The park opened in 1984, and is just to the east of the spot where Bell completed her swim.[39] In 1974, Diana Nyad became the first person who swam across the lake against the current (from north to south).[40] On August 28, 2007, 14-year-old Natalie Lambert from Kingston, Ontario, made the swim, leaving Sackets Harbor, New York, and reaching Kingston's Confederation basin less than 24 hours after she entered the lake.[41] On August 19, 2012, 14-year-old Annaleise Carr became the youngest person to swim across the lake. She completed the 32-mile (52-km) crossing from Niagara-on-the-Lake to Marilyn Bell Park in just under 27 hours.[42]

Industrialisation

The government of Ontario, which holds the lakebed rights of the Canadian portion of the lake under the Beds of Navigable Waters Act,[43] does not permit off-shore wind power to be generated offshore.[44] In Trillium Power Wind Corporation v. Ontario (Natural Resources),[43] the Superior Court of Justice held Trillium Power—since 2004 an "Applicant of Record" who had invested $35,000 in fees and, when in 2011 the Crown made a policy decision against offshore windfarms, claimed an injury of $2.25 billion—disclosed no reasonable cause of action.

While the Great Lakes once supported an industrial-scale fishery, with record hauls in 1899, overfishing later blighted the industry.[45] Today only recreational fishing activities exist.

Lake Ontario is also the site of several major commercial ports including the Port of Toronto and the Port of Hamilton. Hamilton Harbour is also the location of major steel production facilities.

Images

.jpg) Satellite image during late autumn

Satellite image during late autumn The lake seen from dead end of Dutch St.; Huron, New York (A sparsely populated neighboring town of Wolcott, New York)

The lake seen from dead end of Dutch St.; Huron, New York (A sparsely populated neighboring town of Wolcott, New York)

Bathers at Southwick Beach State Park, eastern shore of Lake Ontario, New York State

Bathers at Southwick Beach State Park, eastern shore of Lake Ontario, New York State.jpg) Sodus Outer Light, Sodus Bay, New York

Sodus Outer Light, Sodus Bay, New York View of Lake Ontario from Toronto's CN Tower, showing Toronto Harbour, Toronto Islands, and the island airport

View of Lake Ontario from Toronto's CN Tower, showing Toronto Harbour, Toronto Islands, and the island airport- Pier in Oakville, Ontario

Sculpture at top of Scarborough Bluffs

Sculpture at top of Scarborough Bluffs

Lake Ontario from Prince Edward County, Ontario

Lake Ontario from Prince Edward County, Ontario

See also

- Charity Shoal Crater

- Engagements on Lake Ontario

- Gaasyendietha

- Glacial Lake Admiralty

- Glacial Lake Iroquois

- Iroquois settlement of the northern shores of Lake Ontario

- Lake Ontario Waterkeeper

- Ontario Lacus, a hydrocarbon lake on Saturn's moon Titan named after Lake Ontario

- Wyandot people

Great Lakes in general

- Great Lakes Areas of Concern

- Great Lakes census statistical areas

- Great Lakes Commission

- Great Recycling and Northern Development Canal

- Great Storm of 1913

- International Boundary Waters Treaty

- List of cities along the Great Lakes

- Sixty Years' War for control of the Great Lakes

- Third Coast

References

- National Geophysical Data Center Archived March 23, 2015, at Wikiwix, 1999. Bathymetry of Lake Ontario. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V56H4FBH [access date: March 23, 2015].

- National Geophysical Data Center Archived March 23, 2015, at Wikiwix, 1999. Bathymetry of Lake Erie and Lake Saint Clair. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V5KS6PHK [access date: March 23, 2015]. (only small portion of this map)

- National Geophysical Data Center, 1999. Global Land One-kilometer Base Elevation (GLOBE) v.1. Archived February 24, 2011, at Wikiwix Hastings, D. and P.K. Dunbar. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V52R3PMS [access date: March 16, 2015].

- "About Our Great Lakes: Tour". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) – Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL). Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2015. Google Earth Great Lakes Tour GreatLakesTour_Merged.kmz Archived January 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "Great Lakes: Basic Information: Physical Facts". U.S. Government. May 25, 2011. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- "Great Lakes Atlas: Factsheet #1". United States Environmental Protection Agency. April 11, 2011. Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- Wright 2006, p. 64.

- Shorelines of the Great Lakes Archived April 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- A Report on Water Resources and Local Watershed Management Programs Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The State of the New York Lake Ontario Basin (2000)

- Wilcox, D.A, Thompson, T.A., Booth, R.K., and Nicholas, J.R.. 2007. Lake-level variability and water availability in the Great Lakes. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1311, 25 p.

- Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. Chapter 2.

- Christie, W. J. (1974). Changes in the fish species composition of the Great Lakes. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 31, 827–54.

- Maynard, L., and Wilcox, D.A., 1997, Coastal wetlands of the Great Lakes—State of the Lakes Ecosystem Conference 1996 background paper: Environment Canada and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA 905–R–97–015b, 99 p.

- Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.497 p.

- Origin of drumlins on the floor of Lake Ontario and in upper New York State; Quaternary geology; bridging the gap between East and West — Department of Geology, University of Toronto Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Geology.utoronto.ca (November 17, 2011). Retrieved on November 29, 2011.

- Smith 1987, p. 10.

- Lake Ontario Facts and Figures Archived March 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Great-lakes.net (February 28, 2005). Retrieved on November 29, 2011.

- "L'Amérique française en 1712". Canadian Museum of Civilization. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008.

- "A 1000-Year-Old Nordic Spearhead Raises the Question – Were The Vikings in New York?". Terra Forming Terra. June 10, 2017. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Snider, Charles Henry Jeremiah, Townsend, Robert B. Tales from the Great Lakes. Toronto: Dundurn Press Limited, 1995, pp. 25.

- Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Chapters 1 and 2.

- Wilcox, D.A, Thompson, T.A., Booth, R.K., and Nicholas, J.R. 2007. Lake-level variability and water availability in the Great Lakes. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1311.Box 4

- Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p.

- Moore, D. R. J. and Keddy, P. A. (1989). The relationship between species richness and standing crop in wetlands: the importance of scale. Vegetation, 79, 99–106.

- "Great Lakes". Nature Conservancy Canada. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011.

- Williams, M. 1989. Americans and Their Forests: A Historical Geography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Keddy, C.J. 1993. Forest History of Eastern Ontario. A report prepared for the Eastern Ontario Forest Group.

- Environment Canada. 2004. How Much Habitat is Enough? A Framework for Guiding Habitat Rehabilitation in Great Lakes Areas of Concern. 2nd ed. 81 p.

- Keddy, P.A. and C. G. Drummond. 1996. Ecological properties for the evaluation, management, and restoration of temperate deciduous forest ecosystems. Ecological Applications 6: 748–762.

- Scott, W.B. and E.J. Crossman. 1972. Freshwater Fisheries of Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Department of the Environment, Ottawa. p. 88.

- Vallentyne, J. R. (1974). The Algal Bowl: Lakes and Man, Miscellaneous Special Publication No. 22. Ottawa, ON: Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service.

- Kingston Chronicle, January 30, 1830, 2, col. 6 ("For several years past we have not been visited with so much snow as has fallen here within the last fortnight. The storm of Wednesday and yesterday could only be equalled by such visitations as are familiar to our Lower Canada friends. The thermometer has ranged from 10° below, to 20° above 0, for the last ten days. The Lake is firmly frozen, and a cheap and safe style of travelling has revived the intercourse with our brethren of the independent portion of the world"); Republican Compiler [newspaper], February 23, 1830, p. 2, col. 5 ("At Kingston, Upper Canada, the quantity of snow which had fallen had not been equalled for several years.—The Lake (Ontario) was frozen, and crossing had become general"); Perry, Kenneth A, The Fitch Gazetteer: An Annotated Index to the Manuscript History of Washington County, New York, 4 vols. (Bowie, Md.: Heritage Books, 1999), 4:565 ("Kingston, Upper Canada, [experiencing] the deepset [sic] snow in several yrs., & Lake Ontario frozen over"); Kingston Chronicle [newspaper], January 9, 1830, 2, col. 1 ("the Bay was frozen across this morning"); see also Vermont Chronicle, (Bellows Falls, Vt.) Friday, February 19, 1830, p. 31, col D, quoting the Quebec Gazette: "The Lake (Ontario) was frozen, and crossing had become general."

- May 2008.

- Great Lakes Circle Tour Archived July 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Great-lakes.net (July 5, 2005). Retrieved on November 29, 2011.

- The Morning Post (London, England), Saturday, July 25, 1835; p. 6 "Sea Serpent in Lake Ontario"

- Glasgow Herald (Glasgow, Scotland), Friday, June 28, 1867 "Another Sea Serpent Sensation: A hideous monster discovered in Lake Ontario"

- Pinkwater, Daniel. The Monster of Lake Ontario. New York: Houghton Mifflin Publishing, 2010, pp. 46–47.

- CNN Wire Staff (August 20, 2012). "14-year-old swims solo across Lake Ontario". CNN. Archived from the original on August 20, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- "Plaque in Marilyn Bell Park". YouTube. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- Pitock, Todd. "The Unsinkable Diana Nyad". Reader's Digest (November 2011). Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- "Kingston teen becomes youngest to swim Lake Ontario". CBC. August 28, 2007. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- Alamenciak, Tim (August 20, 2012). "Annaleise outwits Lake Ontario". The Hamilton Spectator. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- "Trillium Power Wind Corporation v. Ontario (Natural Resources), 2012 ONSC 5619 (CanLII)". canlii.org. Archived from the original on August 29, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- Spears, John (February 15, 2013). "Ontario's off-shore wind turbine moratorium unresolved two years later". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- Author unknown (1972). The Great Lakes: An Environmental Atlas and Resource Book. Bi-national (U.S. and Canadian) resource book.

Bibliography

- May, Gary (2008). "The Day the Lake Froze Over". Watershed Magazine (Winter 2008/2009).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Donald B. (1987). Sacred Feather. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-6732-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wright, John W., ed. (2006). The New York Times Almanac (2007 ed.). New York, New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-303820-6.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lake Ontario. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Ontario. |

- Lake Ontario NOAA nautical chart #14820 online

- EPA's Great Lakes Atlas

- Great Lakes Coast Watch

- Lake Ontario Bathymetry