Battle of Stoney Creek

The Battle of Stoney Creek was a British victory over an American force fought on 6 June 1813, during the War of 1812 near present-day Stoney Creek, Ontario. British units made a night attack on the American encampment, and due in large part to the capture of the two senior officers of the American force, and an overestimation of British strength by the Americans, the battle resulted in a total victory for the British, and a turning point in the defence of Upper Canada.

| Battle of Stoney Creek | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

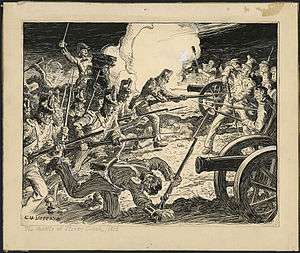

Battle of Stoney Creek, Charles Jefferys | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 700[1] | 3,400[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

159 killed and wounded 52 captured 3 missing[3][4] |

55 killed and wounded 100 captured[5][6] | ||||||

Background

On 27 May, the Americans had won the Battle of Fort George, forcing the British defenders of Fort George into a hasty retreat. The British commander, Brigadier General John Vincent, gathered in all his outposts along the Niagara River, disbanded the militia contingents in his force and retreated to Burlington Heights (at the west end of Burlington Bay), with about 1,600 men in total. The Americans under the overall leadership of General Henry Dearborn, who was elderly and ill, were slow to pursue. A brigade under Brigadier General William H. Winder first followed up Vincent, but Winder decided that Vincent's forces were too strong to engage, and halted at the Forty Mile Creek. Another brigade joined him, commanded by Brigadier General John Chandler, who was the senior, and took overall command. Their combined force, numbering 3,400, advanced to Stoney Creek, where they encamped on 5 June.[7] The two generals set up their headquarters at the gage Farm.[8]

Vincent sent his Deputy Assistant Adjutant General, Lieutenant Colonel John Harvey, to reconnoitre the American position. Harvey recommended a night attack, reporting that "the enemy's guards were few and negligent; his line of encampment was long and broken; his artillery was feebly supported; several of his corps were placed too far to the rear to aid in repelling a blow which might be rapidly struck in front".[9] The American dispositions described by Harvey account for the statement in the post-battle report of the U.S. Assistant Adjutant-General that only 1,328 American troops were engaged against the British, out of Chandler's total force of 3,400.[2] A British column of five companies from the 1/8th (King's) Regiment of Foot and the main body of the 49th Regiment of Foot, about 700 men in all, was formed.[1] Out of the 700 soldiers fighting on the British side, 14 were Canadian locals and the remainder were British regulars.[10] Although Vincent accompanied the column, he placed Harvey in command.[9]

At this point, the story of Billy Green comes to light. Billy Green was a 19-year-old local resident who had witnessed the advance of the Americans from the top of the Niagara Escarpment earlier in the day. Billy's brother-in-law, Isaac Corman, had been briefly captured by the Americans, but was released after he convinced them (truthfully)[11] that he was the cousin of American General William Henry Harrison. In order to be able to pass through the American lines, he was given the challenge response password for the day – "WIL-HEN-HAR" (an abbreviation of Harrison's name). He gave his word of honour that he would not divulge this to the British army. He kept his word, but did reveal the word to Billy Green, who rode his brother-in-law's horse part way, and ran on foot the rest of the way to Burlington Heights. Here, he revealed the password to Lieutenant James FitzGibbon. He was provided with a sword and uniform and used his knowledge of the terrain to guide the British to the American position.[12][13][14] Billy Green was present at the battle.

However, it has been suggested that the password was actually obtained by Lieutenant Colonel Harvey. According to an account given after the war by Frederick Snider, a neighbour of the Gages, Harvey had executed a ruse on the first sentry to be accosted. Pretending to be the American officer of the day making Grand Rounds, he approached the sentry and when challenged, came close to the sentry's ear as if to whisper the countersign. But with bayonet secreted in hand, he grabbed the surprised sentry by the throat and threw him to the ground. With the bayonet at his throat, the sentry gave up the password.[15] This suggestion illustrates the incomplete research into several aspects of the Battle of Stoney Creek. Snider gave this account not long before his death in 1877 [16][17] and his source for it was the April 1871 issue of The Canadian Literary Journal.[18] Snider was confusing Harvey with Colonel Murray, June 1813 with December 1813 and Stoney Creek with Youngstown near Fort Niagara. Snider makes several obvious errors, such as "the British General St. Vincent was found some days after wandering about in the woods nearly dead of hunger." His name was Vincent and he did not wander about the woods for days. Snider's source for the provenance of the countersign should thus be considered to be unreliable.[14]

Battle

The British left their camp at Burlington Heights at 11:30 p.m. on June 5. While Vincent was the senior officer present, the troops were placed under the conduct and direction of Lieutenant Colonel Harvey, who led them silently toward Stoney Creek.[1] They had removed the flints from their muskets to ensure that there were no accidental discharges and dared not utter even a whisper.[13] A sentry post of American soldiers was surprised and either captured or killed by bayonet.[19] Billy Green is said to have bayoneted one of the American sentries personally,[12] although this is not mentioned in any official British record. The British continued advancing toward the American campfires in silence. However at the repeated urging of Second Lieutenant Ephraim Shaler, the U.S. 25th Regiment which had earlier been camped there had been moved from their previous exposed position, leaving behind only the cooks who were preparing the troops' meal for the next day.[20] Shaler had returned to the original position when he heard a sentry cry out as he was being tomahawked after being shot with an arrow from one of John Norton's small band of First Nations warriors.

Around the same time, a group of Vincent's staff officers who had come forward to watch the action let out a cheer.[20] Their men took up the cheer, relieving their tension but depriving them of the element of surprise that was their primary advantage given the lopsided number of troops they faced. Instead of striking fear in their adversaries, the yells served to direct their attention to where the British were, helping the rousing troops to focus their attention and musket fire and making it nearly impossible for officers' orders to be heard above the din. Any hope of catching the Americans unaware and bayoneting them in their sleep was now lost and the British fixed their flints to their muskets and attacked. Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon and three sergeants of the Light Company of the 49th were able to keep their men from taking up the shout "until a late stage of the affair, when firing on our side became general".[21] Gradually, the American troops began to recover from the initial surprise, recover their poise and start firing at the attacking British, at times from as far away as 200 yards (180 m). The American artillery also entered the fray after having previously been rendered useless due to the dampness settling into the powder.[22]

Holding the high ground, the Americans were able to pour both musket and artillery fire into the exposed British line and the line began to lose cohesion. For ammunition, the U.S. Twenty-Fifth Infantry was firing a variant of 'buck and ball', in this instance firing 12 buckshot balls instead of the usual .65 calibre ball and 3 buckshot. This effectively turned their muskets into shotguns.[23] Despite repeated charges by the British, the centre of the American line was holding and with the withering fire that the British line was sustaining, it was only a matter of time before they would have to retire.

A series of events coincided to change the course of the battle. General Winder ordered the U.S. 5th Infantry to protect the left flank. In doing so, he created a gap in the American line while at the same time leaving the artillery unsupported by infantry. Simultaneously, the other American commander, John Chandler, hearing musket shots from the far right of the American line and having already sent his staff officers off with other orders, rode out to investigate personally. But his horse fell (or was shot – Chandler used both excuses at different times) and he was knocked out in the fall.[24]

Major Charles Plenderleath, commanding the British 49th Regiment, was able to ascertain the position of the American artillery when two field guns fired in quick succession (43.218493°N 79.764344°W). Realising the importance of possession of the guns, he gathered troops of Fitzgibbon's and other nearby companies to charge the guns before they could reload. First to volunteer for what could be a suicidal attack were 23-year-old Sergeant Alexander Fraser and his 21-year-old brother Peter, a corporal in Fitzgibbon's company,[25] with 20 to 30 others. With bayonets fixed, Plenderleath led the charge up Gage's Lane, volunteers following at a run, all fearing that the next discharge from the cannons might annihilate them. However, the U.S. 2nd Artillery under the command of Captain Nathaniel Towson at that moment responded to an order to cease firing,[25] unaware of the British troops advancing on their position. The gunners were without arms of their own.[24] The British charged the field guns, and when they were within a few yards of the gun emplacement, the men began yelling "Come on, Brant".[25] They set upon the helpless gunners, bayoneting man and horse, quickly overrunning and capturing the position[26] before continuing on to engage the U.S. 23rd Infantry which got off one round before the momentum of the 49th scattered them.[27] The remaining British forces followed soon after.[28]

At this point General Chandler, conscious again and aware of the commotion near his artillery but not of the reason, stumbled to the position to investigate. Thinking himself to be among the U.S. 23rd Infantry and intending to bring order back to the "new and undisciplined" troops,[29] he realised to his horror that the soldiers were British and Alexander Fraser immediately took him prisoner at bayonet point. Winder very shortly thereafter fell prey to the same mistake. Realising his error, he pulled his pistol, aiming it at Fraser who was poised to take him prisoner as he had Chandler. With his musket pointed at Winder's breast, Fraser told him menacingly "If you stir, sir; you die"[30] and Winder was made prisoner also, proffering his sword to Fraser.[31] Major Joseph Lee Smith of the 25th U.S. Infantry was very nearly captured himself but having made good his escape, alerted his men to make a quick withdrawal, thereby avoiding capture.[32] Command of the American forces fell to cavalry officer Colonel James Burn. The cavalry charged forward firing, but once again in the darkness, the Americans suffered from a case of mistaken identity – they were firing on their own U.S. 16th Infantry, who were themselves wandering around without their commander and firing at each other in confusion. Shortly afterwards, the Americans fell back, convinced that they had been defeated, when in fact they still retained a superior force.[33]

The battle lasted less than 45 minutes, but its intensity led to heavy casualties on both sides.[1] As dawn broke, Harvey ordered the outnumbered British to fall back into the woods in order to hide their small numbers. They succeeded in carrying away two of the captured guns, and spiked two more, leaving them on the ground owing to their inability to move them.[1] They later watched from a distance as the Americans returned to their camp after daybreak, burned their provisions and tents and retreated toward Forty Mile Creek (present day Grimsby, Ontario). By afternoon on 6 June, the British occupied the former site of the American camp.[28]

For much of the morning of 6 June, General Vincent was missing. He had been injured after a fall from his horse during the battle and was found wandering in a state of confusion, convinced that the entire British force had been destroyed. He was finally located about seven miles from the battle scene; his horse, hat and sword all missing.[8][34]

Casualties

The British casualty return gave 23 killed, 136 wounded and 55 missing.[3] Of the men reported as "missing", 52 were captured by the Americans.[4]

The American casualty return for 6 June gave 17 killed, 38 wounded and 7 officers (2 brigadier-generals, 1 major, 3 captains and 1 lieutenant) and 93 enlisted men missing.[5] The British report of prisoners taken on the morning of 6 June corresponds exactly to the American list of "missing" as concerns the number and ranks of the captured officers but gives 94 enlisted men captured,[6] indicating that one of the Americans who was presumed to have been killed in the casualty return was in fact captured. Of the seven officers who were captured on the morning of 6 June, three (Gen. Chandler, Captain Peter Mills and Captain George Steele) were wounded,[35] which suggests that a substantial number of the enlisted prisoners may also have been wounded.

British killed in action at the Battle of Stoney Creek, 6 June 1813 (as listed on the Stoney Creek Battlefield Monument): Samuel Hooker, Joseph Hunt, James Daig, Thomas Fearnsides, Richard Hugill, George Longley, Laurence Mead, John Regler, John Wale, Charles Page, James Adams, Alexander Brown, Michael Burke, Henry Carroll, Nathaniel Catlin, Martin Curley, Martin Donnolly, Peter Henley, John Hostler, Edward Killoran, Edward Little, Patrick Martin, John Maxwell. The names of the American dead are not recorded.

Aftermath

.png)

Casualties in the fight had been uneven, with the British taking roughly three times more killed and wounded than the Americans, but the Americans had been shaken. It is most probable that if their generals had not been captured, the battle might have turned out quite differently.[8] However, the British had a reasonable claim to victory in this battle. Under the de facto leadership of Colonel Harvey, and with some good fortune, they had successfully forced the Americans back toward the Niagara River. American forces would never again advance so far from the Niagara.

At Forty Mile Creek, the retreating American troops were met by reinforcements under Dearborn's second-in-command, Major General Morgan Lewis. Dearborn had ordered Lewis to proceed to Stoney Creek to attack the British, but almost as the two groups met, the British fleet under Captain Sir James Lucas Yeo appeared in Lake Ontario. The American armed vessels under Commodore Isaac Chauncey had abruptly vanished when they heard that Yeo and troops under Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost had attacked their own base at Sackett's Harbor, New York. (The Battle of Sackett's Harbor was a defeat for the British, but large quantities of stores and equipment had mistakenly been set on fire by the Americans, hampering the Americans' efforts to build large fighting vessels.)

With Yeo threatening his communications, which ran for 40 miles (64 km) along the edge of the lake, Lewis decided to retreat at once to Fort George, leaving a large quantity of tents, arms and supplies for the British to acquire. The British vigorously followed up the American withdrawal. A skirmish on 7 June brought in 12 more prisoners; a captain and 11 enlisted men.[6] During 8–10 June 80 more prisoners were taken,[36] making a total American loss, during 6–10 June, of 16 killed, 38 wounded and 192 captured: total 230 men.

The Americans retired into a small defensive perimeter around Fort George, where they remained until abandoning the fort and retreating across the Niagara River into U.S. territory in December.[37]

Brigadier General Winder was later exchanged and subsequently commanded the Tenth Military District around Washington, where he attracted censure following the burning of Washington.

Legacy

Battlefield House remains from the time of the battle, and is a museum located within Battlefield Park. They are located very near the site of the battle and, with a knoll across the street where a separate monument stands, comprises Battle of Stoney Creek National Historic Site.[38][39] The park's stone tower, was dedicated exactly 100 years after the battle. It was unveiled following a signal given by Queen Mary in England, via the transatlantic telegraph cable, and commemorates British soldiers who died in the fight. The Gage farm house is also preserved and serves as a museum. The battle is re-enacted annually on the weekend closest to 6 June.[40] The 2016 event was the 35th such re-enactment.[41]

The battle is commemorated in the song "Billy Green" from the 1999 album From Coffee House to Concert Hall by the late Canadian folk singer Stan Rogers.[42][43] George Fox also sang "Billy Green" which is on his album, Canadian.[44]

References

- Letter, Lt. Col. Harvey to Col. Baynes – 6 June 1813, Cruikshank, p. 7.

- Cruikshank, p. 41.

- J. Harvey, DAAG., Cruikshank, p. 10.

- Cruikshank, p. 30.

- J. Johnson, Asst. Adj. Gen., Cruikshank, p. 25.

- Cruikshank, p. 12.

- H. F. Wood, The Many Battles of Stoney Creek, in Zaslow (ed), p. 57.

- Extract – Niles' Register – Vol 11, pp.116–119, 19 October 1816, Cruikshank, pp. 30–38.

- Zaslow, p. 58.

- Strange Fatality: The Battle of Stoney Creek, 1813 by James Elliot, 2009 pg. 260

- "The Adventures of Billy Green, "The Scout"". Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2009. – Also see Genealogy of Benjamin Harrison IV – who is indicated as being grandfather to William Henry Harrison (via Benjamin Harrison V), and also to Issac Corman (via Sarah Harrison).

- "Battlefield House Museum – Billy Green, the Scout". Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- Berton, pp. 72–80.

- "Green, Philip E.J. 2013. Billy Green the Scout and the Battle of Stoney Creek (June 5–6, 1813). Issue 20, May 3013. War of 1812 Magazine" (PDF). Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Elliot Strange Fatality, p. 115.

- "Frederick G. Snider (1793 - 1877) - Find A Grave Memorial". Findagrave.com. 8 December 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Clark et al., footnotes 34, 35.

- Lubell et al., footnote 44.

- Letter, Lt. James FitzGibbon to Rev. James Somerville – 7 June 1813, Cruikshank, p. 12.

- Elliot, p. 119.

- Stanley, p. 18.

- Elliot, p. 123.

- Elliot, p. 121.

- Elliot, p. 134.

- Elliot, p. 136.

- Hitsman, p. 150.

- Elliot, p. 137.

- Letter, Brigadier General Vincent to Sir George Prevost – 6 June 1813, Cruikshank, p. 8.

- Niles' Weekly Register – 19 October 1816, Battle of Stoney Creek.

- Elliot, p. 138.

- Letter, Brigadier General Chandler to General Dearborn – 18 June 1813, Cruikshank, p. 25.

- Cruikshank, p. 23.

- Berton, p. 78.

- Berton, p. 79.

- Heitman, Volume 2, pp. 17, 31 and 37.

- Cruikshank, p. 64.

- Berton, pp. 79–80.

- Battle of Stoney Creek. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- Battle of Stoney Creek. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- "Battlefield House Museum and Park". Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- Lennie, Laura (27 May 2015). "Annual Re-enactment of the Battle of Stoney Creek just around the corner". Hamilton News. Metroland (a division of the Toronto Star). Retrieved 5 June 2016.

Each year, we strive to ensure that the re-enactment is an event that not only commemorates what occurred at the site over 200 years ago, but also provides historical information related to what was occurring around the world in the early 19th century," Ramsay said. Hundreds of re-enactors ... participate ...

- Baxter-Moore, Nick (Winter 2005). "Recording the War of 1812: Stan Rogers' (Un)sung Heroes". College Quarterly. Seneca College. 8 (1).

- From Coffee House to Concert Hall at AllMusic

- Canadian at AllMusic

Referenced in notes

- Berton, Pierre (1981). Flames Across the Border, 1813 – 1814. Canada: Random House Canada. ISBN 0-385-65838-9.

- Clark, D. B.; Green, D. A.; Lubell, M. (2011). Billy Green and Balderdash (PDF). Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: Stoney Creek Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-9868772-1-6.

- Cruikshank, E. A., ed. (c. 1908). The Documentary History of the Campaign Upon the Niagara Frontier – Part VI. Welland, Ontario: Lundy's Lane Historical Society. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- Elliott, James E. (2009). Strange Fatality: The Battle of Stoney Creek, 1813. Toronto: Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-58-3.

- Green, Philip E. J. (May 2013). "Billy Green the Scout and the Battle of Stoney Creek (June 5-6, 1813)" (PDF). The War of 1812 Magazine. No. 20. napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Heitman, Francis B. (1965) [1903]. Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, from its Organization, 29 September 1789, to 2 March 1903. (Two volumes). Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- Hitsman, J. Mackay (1999). The Incredible War of 1812 – A military History. Cap-Saint-Ignace, Quebec: Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-13-3.

- Lubell, M.; Clark, D. A.; Green, D. (2012). Billy Green and More Balderdash (PDF). Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: Stoney Creek Historical Society.

- Stanley, George F. G. (1991). Battle in the Dark: Stoney Creek, June 6, 1813. Toronto: Balmuir Book Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-919511-46-0.

- Zaslow, Morris (1964). The Defended Border: Upper Canada and the War of 1812. Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada Limited. ISBN 0-7705-1242-9.

General

- John R. Elting, Amateurs to Arms, Da Capo Press, New York, 1995, ISBN 0-306-80653-3.

- Jon Latimer, 1812: War with America, Harvard University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-674-02584-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Stoney Creek. |