Guernsey

Guernsey (/ˈɡɜːrnzi/ (![]()

Guernsey Guernési (Guernésiais) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: "Sarnia Cherie" (Latin) (English: "Dear Guernsey") | |

| |

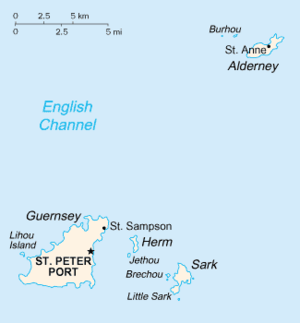

Map of Guernsey within the Bailiwick | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Crown dependency | Bailiwick of Guernsey |

| Separation from the Duchy of Normandy | 1204 |

| Capital and largest city | Saint Peter Port 49°27′36″N 2°32′7″W |

| Official languages | English |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Demonym(s) | Islanders, Guernseymen, Guernseywomen |

| Government | Parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Sir Ian Corder | |

• Bailiff | Richard McMahon |

| Gavin St Pier | |

| Legislature | States of Guernsey |

| Area | |

• Total | 65 km2 (25 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 0 |

| Population | |

• 2019 census | 62,792[1] (207th) |

• Density | 965/km2 (2,499.3/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | £3.272 billion[2] |

• Per capita | £52,531[2] |

| Currency | Guernsey pound[lower-alpha 2] Pound sterling (£) (GBP) |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (GMT) |

| UTC+01:00 (BST) | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +44 |

| UK postcode | |

| ISO 3166 code | GG |

| Internet TLD | .gg |

Constitutional status

The jurisdiction is not part of the United Kingdom, although defence and most foreign relations are handled by the British Government.[3]

The entire jurisdiction lies within the Common Travel Area of the British Islands and the Republic of Ireland. Taken together with the separate jurisdictions of Alderney and Sark it forms the Bailiwick of Guernsey.

The two Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey together form the geographical grouping known as the Channel Islands.

Name

The name "Guernsey", as well as that of neighbouring "Jersey", is of Old Norse origin. The second element of each word, "-ey", is the Old Norse for "island",[4] while the original root, "guern(s)", is of uncertain origin and meaning, possibly deriving from either a personal name such as Grani or Warinn, or from gron, meaning pine tree.[5]

Previous names for the Channel Islands vary over history, but include the Lenur islands,[6] and Sarnia, Sarnia is the Latin name for Guernsey, or Lisia (Guernsey) and Angia (Jersey).

History

Early history

Around 6000 BC, rising seas created the English Channel and separated the Norman promontories that became the bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey from continental Europe.[7] Neolithic farmers then settled on its coast and built the dolmens and menhirs found in the islands today, providing evidence of human presence dating back to around 5000 BC.[8]

Evidence of Roman settlements on the island, and the discovery of amphorae from the Herculaneum area and Spain, show evidence of an intricate trading network with regional and long distance trade.[9] Buildings found in La Plaiderie, St Peter Port dating from 100–400 AD appear to be warehouses.[10] The earliest evidence of shipping was the discovery of a wreck of a ship in St Peter Port harbour, which has been named "Asterix". It is thought to be a 3rd-century Roman cargo vessel and was probably at anchor or grounded when a fire broke out.[11] Travelling from the Kingdom of Gwent, Saint Sampson, later the abbot of Dol in Brittany, is credited with the introduction of Christianity to Guernsey.[12]

Middle Ages

In 933, the Cotentin Peninsula including Avranchin which included the islands, were placed by the French King Ranulf under the control of William I. The island of Guernsey and the other Channel Islands represent the last remnants of the medieval Duchy of Normandy.[12] In 1204, when King John lost the continental portion of the Duchy to Philip II of France, the islands remained part of the kingdom of England.[13] The islands were then recognised by the 1259 Treaty of Paris as part of Henry III's territories.[3]

During the Middle Ages, the island was a haven for pirates that would use the "lamping technique" to ground ships close to her waters. This intensified during the Hundred Years War, when, starting in 1339, the island was occupied by the Capetians on several occasions.[12] The Guernsey Militia was first mentioned as operational in 1331 and would help defend the island for a further 600 years.[14]

In 1372, the island was invaded by Aragonese mercenaries under the command of Owain Lawgoch (remembered as Yvon de Galles), who was in the pay of the French king. Owain and his dark-haired mercenaries were later absorbed into Guernsey legend as invading fairies from across the sea.[15]

Early modern period

As part of the peace between England and France, Pope Sixtus IV issued in 1483 a Papal bull granting the Privilege of Neutrality, by which the Islands, their harbours and seas, as far as the eye can see, were considered neutral territory.[16] Anyone molesting Islanders would be excommunicated. A Royal Charter in 1548 confirmed the neutrality. The French attempted to invade Jersey a year later in 1549 but were defeated by the militia. The neutrality lasted another century, until William III of England abolished the privilege due to privateering activity against Dutch ships.[17]

In the mid-16th century, the island was influenced by Calvinist reformers from Normandy. During the Marian persecutions, three women, the Guernsey Martyrs, were burned at the stake for their Protestant beliefs,[18] along with the infant son of one of the women. The burning of the infant was ordered by Bailiff Hellier Gosselin, with the advice of priests nearby who said the boy should burn due to having inherited moral stain from his mother.[19] Later on Hellier Gosselin fled the island to escape widespread outrage.

During the English Civil War, Guernsey sided with the Parliamentarians. The allegiance was not total, however; there were a few Royalist uprisings in the southwest of the island, while Castle Cornet was occupied by the Governor, Sir Peter Osborne, and Royalist troops. In December 1651, with full honours of war, Castle Cornet surrendered – the last Royalist outpost anywhere in the British Isles to surrender.[20][21]

Wars against France and Spain during the 17th and 18th centuries gave Guernsey shipowners and sea captains the opportunity to exploit the island's proximity to mainland Europe by applying for letters of marque and turning their merchantmen into privateers.

By the beginning of the 18th century, Guernsey's residents were starting to settle in North America,[22] in particular founding Guernsey County in Ohio in 1810.[23] The threat of invasion by Napoleon prompted many defensive structures to be built at the end of that century.[24] The early 19th century saw a dramatic increase in the prosperity of the island, due to its success in the global maritime trade, and the rise of the stone industry. Maritime trade suffered a major decline with the move away from sailing craft as materials such as iron and steel were not available on the island.[25]

Le Braye du Valle was a tidal channel that made the northern extremity of Guernsey, Le Clos du Valle, a tidal island. Le Braye du Valle was drained and reclaimed in 1806 by the British Government as a defence measure. The eastern end of the former channel became the town and harbour (from 1820) of St Sampson's, now the second biggest port in Guernsey. The western end of La Braye is now Le Grand Havre. The roadway called "The Bridge" across the end of the harbour at St Sampson's recalls the bridge that formerly linked the two parts of Guernsey at high tide. New roads were built and main roads metalled for ease of use by the military.[26]

Contemporary period

During the First World War, about 3,000 island men served in the British Expeditionary Force. Of these, about 1,000 served in the Royal Guernsey Light Infantry regiment formed from the Royal Guernsey Militia in 1916.[27]

From 30 June 1940, during the Second World War, the Channel Islands were occupied by German troops. Before the occupation, 80% of Guernsey children had been evacuated to England to live with relatives or strangers during the war. Some children were never reunited with their families.[28] The occupying German forces deported over 1,000 Guernsey residents to camps in southern Germany, notably to the Lager Lindele (Lindele Camp) near Biberach an der Riß and to Laufen. Guernsey was very heavily fortified during World War II, out of all proportion to the island's strategic value. German defences and alterations remain visible, particularly to Castle Cornet and around the northern coast of the island. Guernsey and Jersey were both liberated on 9 May 1945, now celebrated as Liberation Day on the two islands.[29]

During the late 1940s the island repaired the damage caused to its buildings during the occupation. The tomato industry started up again and thrived until the 1970s when the significant increase in world oil prices led to a sharp, terminal decline.[30] Tourism has remained important.[31] Finance businesses grew in the 1970s and expanded in the next two decades and are important employers.[32] Guernsey's constitutional and trading relationships with the United Kingdom and the European Union will be unaffected by Brexit.[33]

Geography

Situated around 49°35′N 2°20′W, Guernsey, Herm and some other smaller islands together have a total area of 71 square kilometres (27 sq mi) and coastlines of about 46 kilometres (29 mi). Elevation varies from sea level to 110 m (360 ft) at Hautnez on Guernsey.

There are many smaller islands, islets, rocks and reefs in Guernsey waters. Combined with a tidal range of 10 metres (33 feet) and fast currents of up to 12 knots, this makes sailing in local waters dangerous. The very large tidal variation provides an environmentally rich inter-tidal zone around the islands, and some sites have received Ramsar Convention designation.[34]

Climate

Guernsey's climate is temperate with mild winters and warm, sunny summers. It is classified as an oceanic climate, with a dry-summer trend, although marginally wetter than mediterranean summers. The warmest months are July and August, when temperatures are generally around 20 °C (68 °F) with some days occasionally going above 24 °C (75 °F). On average, the coldest month is February with an average weekly mean air temperature of 6 °C (42.8 °F). Average weekly mean air temperature reaches 16 °C (60.8 °F) in August. Snow rarely falls and is unlikely to settle, but is most likely to fall in February. The temperature rarely drops below freezing, although strong wind-chill from Arctic winds can sometimes make it feel like it. The rainiest months are December (average 112 mm (4.4 in)), November (average 104 mm (4.09 in)) and January (average 92 mm (3.62 in)). July is, on average, the sunniest month with 250 hours recorded sunshine; December the least with 58 hours recorded sunshine.[35] 50% of the days are overcast.

A number of records were set in 2014. It was the highest annual mean temperature of 12.4 °C (54.3 °F). This is 0.3 °C (0.54 °F) higher than for any other year, due to an almost complete absence of cold snaps during the winter months. Three very wet months meant that the winter was the wettest on record. Halloween turned out to be warmer than any other on record, with the temperature peaking at 18.3 °C (64.9 °F).[36]

| Climate data for Guernsey (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1947–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

30.8 (87.4) |

32.6 (90.7) |

34.3 (93.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

16.6 (61.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

4.6 (40.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.8 (18.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

0.1 (32.2) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 92.5 (3.64) |

70.2 (2.76) |

67.0 (2.64) |

53.1 (2.09) |

50.9 (2.00) |

45.5 (1.79) |

42.1 (1.66) |

47.7 (1.88) |

57.5 (2.26) |

95.0 (3.74) |

104.3 (4.11) |

112.9 (4.44) |

838.7 (33.02) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 19.3 | 15.7 | 15.9 | 13.2 | 11.9 | 10.4 | 11.0 | 10.6 | 12.4 | 17.3 | 18.8 | 18.6 | 175.0 |

| Average snowy days | 2.8 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 11.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 61.0 | 85.6 | 127.6 | 194.7 | 234.5 | 246.6 | 250.7 | 230.1 | 180.1 | 117.1 | 77.8 | 58.2 | 1,864 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22.7 | 29.1 | 34.7 | 47.7 | 49.6 | 51.2 | 51.7 | 52.0 | 47.8 | 35.3 | 28.7 | 22.8 | 41.8 |

| Source: Guernsey Met Office 2018 Weather Report[37] | |||||||||||||

Geology

Guernsey has a geological history stretching further back into the past than most of Europe. It forms part of the geological province of France known as the Armorican Massif.[38] There is a broad geological division between the north and south of the Island. The Southern Metamorphic Complex is elevated above the geologically younger, lower lying Northern Igneous Complex. Guernsey has experienced a complex geological evolution (especially the rocks of the southern complex) with multiple phases of intrusion and deformation recognisable.

Guernsey is composed of nine main rock types, two of which being granites and the rest gneiss.[39]

Politics

Guernsey is a parliamentary representative democracy and legally a British Crown dependency. The Lieutenant Governor of Guernsey is the "representative of the Crown in right of the république of the Bailiwick of Guernsey".[40] The official residence of the Lieutenant Governor is Government House. Since 2016 the incumbent has been Vice Admiral Sir Ian Corder KBE, CB, replacing his predecessor, Air Marshal Peter Walker, who had died in post.[41] The post was created in 1835 as a result of the abolition of the office of Governor. Since that point, the Lieutenant Governor has always resided locally.[42]

States of Guernsey

The deliberative assembly of the States of Guernsey (États de Guernesey) is called the States of Deliberation (États de Délibération) and consists of 38 People's Deputies, elected from multi-member districts every four years. There are also two representatives from Alderney, a semi-autonomous dependency of the Bailiwick, but Sark sends no representative since it has its own legislature. The Bailiff or Deputy Bailiff preside in the assembly. There are also two non-voting members: H.M. Procureur (analogous to the role of Attorney General) and H.M. Comptroller (analogous to Solicitor General), both appointed by the Crown and collectively known as the Law Officers of the Crown.

A projet de loi is the equivalent of a UK bill or a French projet de loi, and a law is the equivalent of a UK act of parliament or a French loi. A draft law passed by the States can have no legal effect until formally approved by Her Majesty in Council and promulgated by means of an order in council.[43] Laws are given the Royal Sanction at regular meetings of the Privy Council in London, after which they are returned to the islands for formal registration at the Royal Court. The States also make delegated legislation known as Ordinances (Ordonnances) and Orders (ordres) which do not require the Royal Assent. Commencement orders are usually in the form of ordinances.

The Policy and Resources Committee is responsible for Guernsey's constitutional and external affairs, developing strategic and corporate policy and coordinating States business. It also examines proposals and Reports placed before Guernsey's Parliament (the States of Deliberation) by Departments and Non States Bodies. The President of the Committee is the de facto head of government of Guernsey.[44]

Legal system

Guernsey's legal system originates in Norman Customary Law, overlaid with principles taken from English common law and Equity as well as from statute law enacted by the competent legislature(s) – usually, but not always, the States of Guernsey. Guernsey has almost complete autonomy over internal affairs and certain external matters. However, the Crown – that is to say, the UK Government – retains an ill-defined reserved power to intervene in the domestic affairs of any of the five Crown Dependencies within the British Islands "in the interests of good government".[45] The UK Parliament is also a source of Guernsey law for those matters which are reserved to the UK, namely defence and foreign affairs.

The head of the bailiwick judiciary in Guernsey is the Bailiff, who, as well as performing the judicial functions of a Chief Justice, is also the head of the States of Guernsey and has certain civic, ceremonial and executive functions. The Bailiff's functions may be exercised by the Deputy Bailiff. The posts of Bailiff and Deputy Bailiff are Crown appointments. Sixteen Jurats, who need no specific legal training, are elected by the States of Election from among Islanders. They act as a jury, as judges in civil and criminal cases and fix the sentence in criminal cases. First mentioned in 1179, there is a list of Jurats who have served since 1299.[46]

The oldest Courts of Guernsey can be traced back to the 9th century. The principal court is the Royal Court and exercises both civil and criminal jurisdiction. Additional courts, such as the Magistrate's Court, which deals with minor criminal matters, and the Court of Appeal, which hears appeals from the Royal Court, have been added to the Island's legal system over the years.

External relations

Several European countries have a consular presence within the jurisdiction. The French Consulate is based at Victor Hugo's former residence at Hauteville House.[47]

While the jurisdiction of Guernsey has complete autonomy over internal affairs and certain external matters, the topic of complete independence from the British Crown has been discussed widely and frequently, with ideas ranging from Guernsey obtaining independence as a Dominion to the bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey uniting and forming an independent Federal State within the Commonwealth, whereby both islands retain their independence with regards to domestic affairs but internationally, the islands would be regarded as one state.[12]

Although it is not a member of the European Union, it had a special relationship with it until Brexit. It was treated as part of the European Community with access to the single market for the purposes of the free trade in goods.

Parishes

%2C_administrative_divisions_-_de_-_colored.svg.png)

Guernsey has ten parishes, which act as civil administration districts with limited powers. Each parish is administered by a Douzaine, usually made up of twelve members, known as Douzeniers. Douzeniers are elected for a four-year mandate, two Douzeniers being elected by parishioners at a parish meeting in November each year. The senior Douzenier is known as the Doyen (Dean). Two elected Constables (Connétables) carry out the decisions of the Douzaine, serving for between one and three years. The longest serving Constable is known as the Senior Constable and his or her colleague as the Junior Constable.[48] The Douzaines levy an Occupiers Rate on properties to provide funding for running of the administration.[49]

Guernsey's Church of England parishes fall under the See of Canterbury, having split from the Bishopric of Winchester in 2014.[50] The biggest parish is Castel, while the most populated is St Peter Port.

Economy

Financial services, such as banking, fund management, and insurance, account for about 37% of GDP.[51] Tourism, manufacturing, and horticulture, mainly tomatoes and cut flowers, especially freesias, have been declining.[30] Light tax and death duties make Guernsey a popular offshore finance centre for private equity funds.

Guernsey does not have a Central Bank and it issues its own sterling coinage and banknotes. UK coinage and (English, Scottish and Northern Irish-faced) banknotes also circulate freely and interchangeably.[52] Total island investment funds, used to fund pensions and future island costs, amount to £2.7billion as at June 2016.[53] The island issued a 30-year bond in December 2015 for £330m, its first bond in 80 years.[54] The island has been given a credit rating of AA-/A-1+ with a stable outlook from Standard & Poor's.[55]

Guernsey has the official ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 code GG and the official ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 code GGY; market data vendors, such as Reuters, will report products related to Guernsey using the alpha-3 code.

In March 2016 there were over 32,291 people employed in Guernsey with 4,864 being self-employed. 2,453 employing businesses. 19.6% work in the finance industry and median earnings were £31,215.[56]

Infrastructure

Public services, such as water, wastewater, the two main harbours and the airport are still owned and controlled by the States of Guernsey. The electricity, and postal services have been commercialised by the States and are now operated by companies wholly owned by the States of Guernsey. Gas is supplied by an independent private company. In 1998, Guernsey and Jersey jointly formed the Channel Islands Electricity Grid to operate and manage the submarine cables between Europe and the Channel Islands.[57] The installation of these cables was originally to provide the island with a secure form of backup power but now are effectively the primary source of power with the local diesel generators providing back-up.[58]

Guernsey Telecoms, which provided telecommunications, was sold by the States to Cable & Wireless plc, rebranded as Sure and was sold to Batelco in April 2013. Newtel was the first alternative telecommunications company on the island and was acquired by Wave Telecom in 2010[59] and subsequently rebranded as Jersey Telecom.[60] Airtel-Vodafone also provide a mobile network.[61]

Both the Guernsey Post postal boxes (since 1969) and the telephone boxes (since 2002) are painted blue, but otherwise are identical to their British counterparts, the red pillar box and red telephone box. In 2009 the telephone boxes at the bus station were painted yellow just like they used to be when Guernsey Telecoms was state-owned. The oldest pillar box still in use in the British Isles can be found in Union Street, St Peter Port and dates back to 1853.[62]

_takes_off_from_Bristol_Airport%2C_England_8Sept2016_arp.jpg)

Transport

Ports and harbours exist at St Peter Port and St Sampson. There is a single paved airport, Guernsey Airport. The States of Guernsey wholly own their own airline, Aurigny. The decision to purchase the airline was made to protect important air links to and from the island and the sale was completed on 15 May 2003.

The Guernsey Railway, effectively an electric tramway, began working on 20 February 1892 and was abandoned on 9 June 1934. It replaced an earlier transport system which was worked by steam, the Guernsey Steam Tramway, which had operated from 6 June 1879 with six locomotives. Alderney is now the only Channel Island with a working railway.[63]

A narrow gauge railway was built by the German forces during WW2 to transport materials used in the construction of coastal defenses. This was removed after the War.

Guernsey has a public bus service, operated by CT Plus on behalf of the States of Guernsey Environment and Infrastructure Department.[64]

Business

As of 2014, the finance industry forms the largest economic sector in Guernsey, generating around 40% of Guernsey's GDP and directly employing around 21% of its workforce.[65] Banks began setting up operations in the island from the early 1960s onwards in order to avoid high onshore taxes and restrictive regulation.[32] The industry regulator is the Guernsey Financial Services Commission, which was established in 1987.[66]

Prior to the growth of the finance industry, the island's main industries were quarrying and horticulture. The latter particularly decline as a result of the oil price shocks of the 1970s and the introduction of cheap North Sea gas that benefited Dutch growers.[32] Guernsey is home to Specsavers Optical Group and Healthspan also has its headquarters in Guernsey.[67]

Tourism

Guernsey has been a tourist destination since at least the Victorian days, with the first tourist guide published in 1834. In the 19th century, two rail companies (London and South Western Railway and Great Western Railway[68]) ran competing boats from the UK mainland to St Peter Port, with a race to the only convenient berth. This was halted with the sinking of the SS Stella in 1899.[69]

Guernsey enters Britain in Bloom with St Martin Parish winning the small town category twice in 2006 and 2011,[70] Saint Peter Port winning the large coastal category in 2014 and St Peter's winning the small coastal prize in 2015.[71] Herm has won Britain in Bloom categories several times:[72] in 2002, 2008, and 2012, Herm won the Britain in Bloom Gold Award.[73]

The military history of the island has left a number of fortifications, including Castle Cornet, Fort Grey. Guernsey loophole towers and a large collection of German fortifications with a number of museums.

The use of the roadstead in front of St Peter Port by over 100 cruise ships a year is bringing over 100,000-day trip passengers to the island each year.[74]

Taxation

Guernsey, Alderney and Sark each raise their own taxation,[75] although in 1949 Alderney (but not Sark) transferred its fiscal rights to Guernsey.[76]

Personal tax liability differs according to whether an individual is resident in the island or not. Individuals resident in the Jurisdiction of Guernsey (which does not include Sark) pay income tax at the rate of 20% on their worldwide income, whereas non-residents are only liable on income arising from activity or ownership within Guernsey. Unlike in the UK, the income tax year in Guernsey aligns to the calendar year.[77] All Guernsey-resident individuals are subject an upper limit on their tax liability, which is known as the "tax cap". Individuals may elect either of the following; Tax on non-Guernsey-source income restricted to £110,000, plus tax on Guernsey-source income (excluding Guernsey bank interest), or Taxed on worldwide income restricted to £220,000, including Guernsey-source income. Income derived from Guernsey land and property is excluded from the tax cap, as from 1 January 2015, and is subject to tax at the normal rate of 20%. Only one cap applies per married couple.[78] As from 1 Jan 2019, these tax caps have increased to £130,000 and £260,000 respectively.[79] Guernsey has also introduced a new lower £50k tax cap for new residents for three years, subject to buying an Open Market Part A house with a document duty in excess of that amount, and not having lived in Guernsey or Alderney for three years prior.[80]

Since 2008, Guernsey has operated three levels of corporation tax, depending on the source of the income.

- A 0% corporation tax rate on most companies.

- A 10% rate (income from banking business and, with effect from 1 January 2013, extended to domestic insurance business, fiduciary business, insurance intermediary business and insurance manager business).

- A 20% rate (income from trading activities regulated by the Office of the Director General of Utility Regulation, and income from the ownership of lands and buildings).[81]

Guernsey levies no capital gains, inheritance, capital transfer, value added (VAT / TVA) or general withholding taxes.[82] In the 2011 Budget, the UK announced that it would be ending Low Value Consignment Relief that was being used to sell goods VAT free to customers across the UK, with this legislation coming into force on 1 April 2012.[83] Tax revenues represent 22.4% of GDP.[84]

Social Security contributions, a form of taxation, are payable by most residents, employees paying 6.6%, self employed 11% and non employed 10.4%, all subject to upper and lower limits.

Society

Demographics

The population is 63,026 (July 2016 est.)[1] The median age for males is 40 years and for females is 42 years. The population growth rate is 0.775% with 9.62 births/1,000 population, 8 deaths/1,000 population, and annual net migration of 6.07/1,000 population. The life expectancy is 80.1 years for males and 84.5 years for females.[85] The Bailiwick ranked 10th in the world in 2015 with an average life expectancy of 82.47 years.[86]

Border control

The whole jurisdiction of Guernsey is part of the Common Travel Area.[87]

For immigration and nationality purposes it is UK law, and not Guernsey law, which applies (technically the Immigration Act 1971,[88] extended to Guernsey by Order-in-Council). Guernsey may not apply different immigration controls to the UK.

Housing restrictions

Guernsey undertakes a population management mechanism using restrictions over who may work in the island through control of which properties people may live in. The housing market is split between local market properties and a set number of open market properties.[89] Anyone may live in an open market property, but local market properties can only be lived in by those who qualify – either through being born in Guernsey (to at least one local parent), by obtaining a housing licence, or by virtue of sharing a property with someone who does qualify (living en famille). Consequently, open market properties are much more expensive both to buy and to rent. Housing licences are for fixed periods, often only valid for 4 years and only as long as the individual remains employed by a specified Guernsey employer. The licence will specify the type of accommodation and be specific to the address the person lives in,[90] and is often subject to a police record check. These restrictions apply equally regardless of whether the property is owned or rented, and only apply to occupation of the property. Thus a person whose housing licence expires may continue to own a Guernsey property, but will no longer be able to live in it. There are no restrictions on who may own a property.

There are a number of routes to qualifying as a "local" for housing purposes. Generally, it is sufficient to be born to at least one Guernsey parent and to live in the island for ten years in a twenty-year period. In a similar way a partner (married or otherwise) of a local can acquire local status. Multiple problems arise following early separation of couples, especially if they have young children or if a local partner dies, in these situations personal circumstances and compassion can add weight to requests for local status. Once "local" status has been achieved it remains in place for life. Even a lengthy period of residence outside Guernsey does not invalidate "local" housing status.[91]

Although Guernsey's inhabitants are full British citizens,[92] an endorsement restricting the right of establishment in other European Union states is placed in the passport of British citizens connected solely with the Channel Islands and Isle of Man. If classified with "Islander Status", the British passport will be endorsed as follows: 'The holder is not entitled to benefit from EU provisions relating to employment or establishment'. Those who have a parent or grandparent born in the United Kingdom itself (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), or who have lived in the United Kingdom for 5 years, are not subject to this restriction.[93]

Education

Teaching in Guernsey is based on the English National Curriculum. There are 10 primary schools, plus two junior schools and three infant schools. As of 2017, the island still has the 11-plus exam and pupils then transfer to one of four 11–16 secondary schools, or a co-educational grammar school.[94] There are also three fee-paying colleges with lower schools, for which pupils over 11 receive grant support from the States of Guernsey. In 2016, the States of Guernsey voted to end the use of the 11-plus exams from 2019 onwards.[95] It is also responsible for education on the neighbouring islands.[96]

The Education Department is part way through a programme of re-building its secondary schools. The Department has completed the building of Le Rondin special needs school, the Sixth Form Centre at the Grammar School and the first phase of the new College of Further Education – a performing arts centre. The construction of St Sampsons High was completed summer 2008 and admitted its first pupils in September 2008.

In 2008, the school leaving age was raised so the earliest date is the last Friday in June in the year a pupil turns 16, in line with England, Wales and Northern Ireland. This means pupils will be between 15 and 10 months and 16 and 10 months before being able to leave. Prior to this, pupils could leave school at the end of the term in which they turned 14, if they so wished: a letter was required to be sent to the Education department to confirm this. However, this option was undertaken by relatively few pupils, the majority choosing to complete their GCSEs and then either begin employment or continue their education.

Post-GCSE pupils have a choice of transferring to the state-run Grammar School & Sixth Form Centre, or to the independent colleges for academic AS/A Levels/International Baccalureate Diploma Programme. They also have the option to study vocational subjects at the island's Guernsey College of Further Education.

There are no universities in the island. Students who attend university in the United Kingdom receive state support towards both maintenance and tuition fees. In 2007, the Education Department received the approval of the States Assembly to introduce student contributions to the costs of higher education, in the form of student loans, as apply in the UK. However, immediately after the general election of 2008, the States Assembly voted in favour of a Requête which proposed abolishing the student loans scheme on the grounds that it was expensive to run and would potentially discourage students from going to, and then returning to the island from, university. In 2012, the Education Department reported to the States Assembly that it had no need to re-examine the basis of higher education funding at the present time.

Culture

The French impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir visited the island in late summer 1883. While on the island, he painted fifteen pictures of the views on the island, all featuring the bay and beach of Moulin Huet on the south coast.[97]

The Guernsey cattle is an internationally famous icon of the island. As well as being prized for its rich creamy milk, which is claimed to hold health benefits over milk from other breeds,[98] Guernsey cattle are increasingly being raised for their distinctively flavoured and rich yellowy-fatted beef, with butter made from the milk of Guernsey cows also has a distinctive yellow colour.[99] Since the 1960s the number of individual islanders raising these cattle for private supply has diminished significantly, Guernsey steers can still be occasionally seen grazing on L'Ancresse common.[100]

Guernsey also hosts a breed of goat known as the Golden Guernsey, distinguished by its golden-coloured coat. At the end of the Second World War, the Golden Guernsey had almost been rendered extinct due to interbreeding on the island. The survival of this breed is largely credited to the work of a single woman, Miriam Milbourne, who successfully hid her herd from the Germans during the occupation.[101] Although no longer considered to be critically endangered, the breed remains on the watchlist of the Rare Breeds Survival Trust.[102] The traditional explanation for the donkey (âne in French and Guernésiais) is the steepness of St Peter Port streets that necessitated beasts of burden for transport (in contrast to the flat terrain of the rival capital of St Helier in Jersey), although it is also used in reference to Guernsey inhabitants' stubbornness. In turn, Guernseymen traditionally refer to Jerseymen as crapauds ("toads").[103]

The so-called Guernsey Lily, Nerine sarniensis, is also used as a symbol of the island, although this species was introduced to the island from South Africa.[104]

A local delicacy is the ormer (Haliotis tuberculata), a variety of abalone harvested under strict laws from beaches at low spring tides.[105] Traditional Guernsey recipes include a stew called Guernsey Bean Jar, that is particularly served at the annual Viaer Marchi festival.[106] Chief ingredients include haricot and butter beans, pork and shin beef. Guernsey Gâche is a special bread made with raisins, sultanas and mixed peel.[107]

Languages

English is the language in general use by the majority of the population, while Guernésiais, the Norman language of the island, is spoken fluently by only about 2% of the population (according to 2001 census). However, 14% of the population claim some understanding of the language. Until the early 20th-century French was the only official language of the Bailiwick, and all deeds for the sale and purchase of real estate in Guernsey were written in French until 1971. Family and place names reflect this linguistic heritage. George Métivier, a poet, wrote in Guernesiais. The loss of the island's language and the Anglicisation of its culture, which began in the 19th century and proceeded inexorably for a century, accelerated sharply when the majority of the island's school children were evacuated to the UK for five years during the German occupation of 1940–45.

Literature

Victor Hugo, having arrived on Halloween 1855,[108] wrote some of his best-known works while in exile in Guernsey, including Les Misérables. His home in St Peter Port, Hauteville House, is now a museum administered by the city of Paris. In 1866, he published a novel set on Guernsey, Travailleurs de la Mer (Toilers of the Sea), which he dedicated to the island. Guernsey was his home for fifteen years.[108]

Mabel Collins (1851–1927), a theosophist and prolific author, was born in St Peter Port, Guernsey.

Guernseyman G. B. Edwards wrote a critically acclaimed novel, The Book of Ebenezer Le Page that was published in 1981, including insights into Guernsey life during the 20th century.[109][110] In September 2008, a blue plaque was affixed to the house on the Braye Road where Edwards was raised.[111]

Henry Watson Fowler moved to Guernsey in 1903. He and his brother Francis George Fowler composed The King's English, the Concise Oxford Dictionary and much of Modern English Usage on the island.[112]

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, a novel by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, describes the Occupation of Germans during WWII. Written in 2009, it is about a writer who begins corresponding with residents of the island, and becomes compelled to visit the island. A film adaptation starring Lily James and Jessica Brown Findlay was released in 2018.

Sport

Guernsey participates in the biennial Island Games, which it hosted in 1987 and 2003 at Footes Lane.[113] Guernsey has also participated as a country in its own right in Commonwealth Games since 1970. Its first medals came in 1982 with its first gold in 1990.[114]

In those sporting events where Guernsey does not have international representation, but the British Home Nations are competing separately, highly skilled islanders may choose to compete for any of the Home Nations. There are, however, restrictions on subsequent transfers to represent other Home Nations. The football player Matt Le Tissier, for example, could have played for the Scottish or Welsh football teams, but opted to play for England instead.

Football in Guernsey is run by the Guernsey Football Association. The top tier of Guernsey football is the FNB Priaulx League where there are nine teams (Alderney, Belgrave Wanderers, Manzur, Northerners, Sylvans, St Martin's, Rovers, Rangers and Vale Recreation). The second tier is the Jackson League. In the 2011–12 season, Guernsey F.C. was formed and entered the Combined Counties League Division 1, becoming the first Channel Island club ever to compete in the English leagues. Guernsey became division champions comfortably on 24 March 2012,[115] they won the Combined Counties Premier Challenge Cup on 4 May 2012.[116] Their second season saw them promoted again on the final day in front of 1,754 'Green Lions' fans, this time to Division One South of the Isthmian League,[117][118] despite their fixtures being heavily affected not only by poor winter weather, but by their notable progression to the semi-finals of the FA Vase cup competition.[119] They play in level 8 of the English football pyramid. The Corbet Football Field, donated by Jurat Wilfred Corbet OBE in 1932, has fostered the sport greatly over the years. Recently, the island upgraded to a larger, better-quality stadium, in Footes Lane.[120]

Guernsey has the second oldest tennis club in the world, at Kings[121] (founded in 1857[122]), with courts built in 1875. The island has produced a world class tennis player in Heather Watson as well as professional squash players in Martine Le Moignan, Lisa Opie and Chris Simpson.[121]

Guernsey was declared an affiliate member by the International Cricket Council (ICC) in 2005 and an associate member in 2008.[123] The Guernsey cricket team plays in the World Cricket League and European Cricket Championship as well as the Sussex Cricket League.

Various forms of motorsport take place on the island, including races on the sands on Vazon beach as well as a quarter-mile "sprint" along the Vazon coast road. Le Val des Terres, a steeply winding road rising south from St Peter Port to Fort George, is often the focus of both local and international hill-climb races. In addition, the 2005, 2006 and 2007 World Touring Car Champion Andy Priaulx is a Guernseyman.[124]

The racecourse on L'Ancresse Common was re-established in 2004 after a gap of 13 years, with the first new race occurring on 2 May 2005.[125] Races are held on most May day bank holidays, with competitors from Guernsey as well as Jersey, France and the UK participating. Sea angling around Guernsey and the other islands in the Bailiwick from shore or boat is a popular pastime for both locals and visitors with the Bailiwick boasting multiple UK records.[126]

See also

References

Notes

- Extinct language.

- The Guernsey pound is not a separate currency, but a local issue of standard pound sterling.

Citations

- "Population, Employment and Earnings - States of Guernsey". March 2019.

- "Guernsey Annual GVA and GDP Bulletin - 2018". gov.gg. States of Guernsey. 15 August 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Ogier, Daryl Mark (2005). The Government and Law of Guernsey. The States of Guernsey. ISBN 978-0954977504.

- "Old Norse Words in the Norman Dialect". Viking Network. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Hocart, Richard (2010). Guernsey's Countryside: An Introduction to the History of the Rural Landscape. Guernsey: Societé Guernesiaise. ISBN 978-0953254798.

- "Guernsey, Channel Islands, UK". BBC. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- "La Cotte Cave, St Brelade". Société Jersiaise. Archived from the original on 23 March 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- "Guernsey Attractions – Ancient Monuments". Island Life. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Sebire 2005, p. 107

- Sebire 2005, p. 110

- "Gallo-Roman Ship". Guernsey Museums & Galleries. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Marr, James (2001). The History of Guernsey – The Bailiwick's Story. The Guernsey Press. ISBN 978-0953916610.

- Crossan 2015, p. 7

- "Royal Guernsey Militia Regimental Museum". Guernsey Museums & Galleries. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- de Garis, Marie (1986). Folklore of Guernsey. OCLC 19840362.

- Cooper 2006, p. 13

- Wimbush, Henry (1924). The Channel Islands. A&C Black. p. 89.

- Ogier, Daryl Mark (1997). Reformation and Society in Guernsey. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0851156033.

- Pleading the Belly: A Sparing Plea? Pregnant Convicts and the Courts in Medieval England by Sara M. Butler in Crossing Borders: Boundaries and Margins in Medieval and Early Modern Britain DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004364950_009

- The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 65. p. 621.

- "History of the Castle". Guernsey Museums & Galleries. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Guernsey's emigrant children". BBC Legacies. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Jamieson 1986, p. 281

- "18th & 19th Century Defences". Guernsey Museums & Galleries. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Jamieson 1986, p. 291

- Crossan 2015, p. 241

- Parks, Edwin (1992). Diex Aix: God Help Us – The Guernseymen who marched away 1914–1918. Guernsey: States of Guernsey. ISBN 978-1871560855.

- "Evacuees from Guernsey recall life in Scotland". BBC News. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- "Learn more about Liberation Day". Visit Guernsey. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- "The tomato growing industry". Local History Guernsey. BBC. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- "Guernsey Tourism Strategic Plan 2015–2025" (PDF). VisitGuernsey Trade and Media. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Crossan 2015, p. 17

- "Inside Brexit – Guernsey's Response" (PDF). We are Guernsey. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- "Nature Reserves". www.gov.gg. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- "Met Observatory Weather and Climate Info". Guernsey Airport. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- "2014 Weather Report" (PDF). Guernsey Met Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "2014 Weather Report" (PDF). Guernsey Met Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Renouf, John (May 1985). "Geological excursion guide 1: Jersey and Guernsey, Channel Islands". Geology Today. 1 (3): 90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2451.1985.tb00293.x.

- "Geology and Geography". La Société Guernesiaise. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Review of the Roles of the Jersey Crown officers" (PDF). 30 March 2010. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "Guernsey's Lieutenant Governor: Vice Admiral Ian Corder sworn in". BBC News. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Crossan 2015, p. 8

- Dawes, Gordon (2003). Laws of Guernsey. Oxford: Hart Publishing. ISBN 978-1847311856.

- "Policy & Resources". States of Guernsey.

- Hotchkiss v. Channel Islands Knitwear Company Limited, 207 (2001).

- "Jurats". Guernsey Royal Court.

- "Consulate of France in Guernsey, United Kingdom". Embassypages.com. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Parochial Officers". St Peter Port Parish. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Parishes and Douzaines". The Royal Court of Guernsey. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- "Channel Islands' Anglican churches pay Parish Shares to Canterbury". BBC News. 13 April 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Guernsey Gross Domestic Product First Release 2010". States of Guernsey. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- "About Guernsey". Visitguernsey.com. Archived from the original on 29 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "Total States Funds = £2.7 Billion". Island FM. 28 September 2016.

- "Guernsey's Debt Draws Strong Demand". Wall Street Journal.

- "Island Credit Rating Remains The Same". Island fm. 30 January 2017. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Guernsey Quarterly Population, Employment and Earnings Bulletin" (PDF). Island FM. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "The CIEG Ltd". Guernsey Electric. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "Channel Islands Electricity Grid Project" (PDF). ABB. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "Wave buys Newtel". Guernsey Press. 25 August 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- "Guernsey – A fresh look to mark the tenth birthday of Wave Telecom". JT Global. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- "Guernsey Airtel Launches Services". Airtel. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- "Well adapted for the purpose..." The British Postal Museum & Archive blog.

- Notes on the Railway taken from The Railway Magazine, September 1934 edition.

- "Using the bus service". buses.gg. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- "Guernsey Financial Services – A Strategy for the Future". Gov.GG. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "Locations – Guernsey". Blenheim Group. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "About Healthspan". Healthspan.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "The Wreck of the Stella – Titanic of the Channel Islands". Guernsey Museums and Galleries. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- "Guernsey History Timeline for Schools". Guernsey Museums and Galleries. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- "Where is the greenest, cleanest, prettiest place in Britain?". RHS.

- "St Peter's wins class in national Britain in Bloom". Guernsey press.

- "Herm aims for fourth gold medal in Britain in Bloom". BBC. 27 January 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- "Herm Garden Tour". Herm Island. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Record year for cruise ship passengers in Guernsey". BBC. 10 October 2015.

- "Background briefing on the Crown Dependencies: Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man" (PDF). Ministry of Justice.

- ""The Alderney (Application of Legislation) Law, 1948". Act of 22 December 1948. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- "Guernsey Income Tax". States of Guernsey. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "2018 Tax Guide Summary – Guernsey" (PDF).

- "Guernsey 2019 Tax cap updates – PWC".

- "Guernsey Tax Office Tax Cap rules".

- "Tax for businesses, companies and employers". Gov.GG. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "Guernsey Tax". Locate Guernsey. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "Government ends exploitation of Channel Islands VAT rules". UK Government. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "Guernsey Facts and Figures". States of Guernsey. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- "Health Profile for Guernsey and Alderney". States of Guernsey Public Health Services. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Life Expectancy at Birth". CIA World Factbook.

- "Guidance – Common travel area (CTA)". UK Visas and Immigration. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- "Immigration Act 1971", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1971 c. 77

- "Guernsey's Two Tier Housing Market". States of Guernsey. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015.

- "Where can licence holders live". States of Guernsey. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015.

- "What is a Qualified Resident?". States of Guernsey. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015.

- "British Nationality Act 1981", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1981 c. 61

- "What is Islander status?". States of Guernsey. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013.

- "Selection at 11 (the 11+ process)". Gov.GG. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Guernsey 11-plus vote: End of selection confirmed by States vote". BBC News. 2 December 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Teaching in the Channel Islands". Times Educational Supplement. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- House, John (1988). Renoir in Guernsey. Guernsey Museum & Art Gallery. p. 3. ISBN 978-1871560817. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Milk protein blamed for heart disease". BBC News – Health. 9 April 2001. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- Lewis, Samuel (1831). A Topographical Dictionary of England. London: S Lewis and Co.

- "Grazing returns to L'Ancresse Common". Birds on the Edge. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Watson, Angus (4 May 2007). "Alive and kicking". Financial Times. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- "A Brief History of the Golden Guernsey Goat". Golden Guernsey Goat Society. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Jersey toad is unique species, say experts". BBC News. 9 October 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Nerine sarniensis". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Ormers". Visit Guernsey. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Guernsey Bean Jar". BBC. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Guernsey Gâche". BBC. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Cooper 2006, p. 19

- "A Novel of Life in a Small World". The New York Times. 19 April 1981. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Chaney, Edward, GB Edwards and Ebenezer Le Page, Review of the Guernsey Society, Parts 1–3, 1994–95.

- "A plaque for G.B. Edwards". BBC. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- "H.W. Fowler, the King of English". The New York Times. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Games Reports & Results". International Island Games Association. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Guernsey – Introduction". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- "Guernsey FC secure Combined Counties Division One title,". BBC Sport. 24 March 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Guernsey Press (7 May 2012). "'Dom'-inating Green Lions finally get just rewards". thisisguernsey. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "Guernsey FC: Fourth Win in Four Days Earns Promotion,". BBC Sport. 6 May 2013.

- "Ryman here we come". Guernsey Press. 8 May 2013.

- "Guernsey FC lose FA Vase semi-final first leg to Spennymoor". BBC Sport. 23 March 2013.

- "BBC photo of Guernsey Stadium". Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "The Kings Story". Kings Premier Health Club. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- "Island Archives acquires Guernsey Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club historical material". Gov.GG. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- "Guernsey". International Cricket Council. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- "Andy Priaulx". Chip Ganassi Racing. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Connaughton, Mick (31 August 2004). "Racing: Guernsey racecourse ready for revival after gap of 13 years". The Independent. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- Petch, Thomas (26 January 2013). "British Sea Fish Records". Anglers Mail. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

Sources

- Cooper, Glynis (2006). Foul deeds & suspicious deaths in Guernsey. Wharncliffe Books. ISBN 978-1845630089.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crossan, Rose-Marie (2015). Poverty and Welfare in Guernsey, 1560–2015. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1783270408.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jamieson, A.G. (1986). A people of the sea. Methuen. ISBN 978-0416405408.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sebire, Heather (2005). The Archaeology and Early history of the Channel Islands. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752434490.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Guernsey. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guernsey. |

| Look up guernsey in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Countries.png)