Fulvestrant

Fulvestrant, sold under the brand name Faslodex among others, is a medication used to treat hormone receptor (HR)-positive metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women with disease progression as well as HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer in combination with palbociclib in women with disease progression after endocrine therapy.[2] It is given by injection into a muscle.[3]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Faslodex, others |

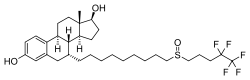

| Other names | ICI-182780; ZD-182780; ZD-9238; 7α-[9-[(4,4,5,5,5-Pentafluoropentyl)-sulfinyl]nonyl]estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular injection |

| Drug class | Antiestrogen |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Low[1] |

| Protein binding | 99%[1] |

| Metabolism | Hydroxylation, conjugation (glucuronidation, sulfation)[1] |

| Elimination half-life | IM: 40–50 days[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.170.955 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C32H47F5O3S |

| Molar mass | 606.78 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Fulvestrant is a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD) and was first-in-class to be approved.[4] It works by binding to the estrogen receptor and destabilizing it, causing the cell's normal protein degradation processes to destroy it.[4]

Fulvestrant was approved for medical use in the United States in 2002.[5]

Medical uses

Breast cancer

Fulvestrant is used for the treatment of hormone receptor positive metastatic breast cancer or locally advanced unresectable disease in postmenopausal women; it is given by injection.[3] A 2017 Cochrane review found it is as safe and effective as first line or second line endocrine therapy.[3]

It is also used to treat HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer in combination with palbociclib in women with disease progression after first-line endocrine therapy.[2]

Due to the medication's having a chemical structure similar to that of estrogen, it can interact with immunoassays for blood estradiol concentrations and show falsely elevated results.[6] This can improperly lead to discontinuing the treatment.[6]

Early puberty

Fulvestrant has been used in the treatment of peripheral precocious puberty in girls with McCune–Albright syndrome.[7][8][9]

Contraindications

Fulvestrant should not be used in women with kidney failure or who are pregnant.[2][10]

Side effects

Very common (occurring in more than 10% of people) adverse effects include nausea, injection site reactions, weakness, and elevated transaminases. Common (between 1% and 10%) adverse effects include urinary tract infections, hypersensitivity reactions, loss of appetite, headache, blood clots in veins, hot flushes, vomiting, diarrhea, elevated bilirubin, rashes, and back pain.[10] In a large clinical trial, the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with fulvestrant was 0.9%.[2]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Fulvestrant is an antiestrogen which acts as an antagonist of the estrogen receptor (ER) and additionally as a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD).[4] It works by binding to the estrogen receptor and making it more hydrophobic, which makes the receptor unstable and misfold, which in turn leads normal processes inside the cell to degrade it.[4] In addition to its antiestrogenic activity, fulvestrant is an agonist of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), albeit with relatively low affinity (10–100 nM, relative to 3–6 nM for estradiol).[11][12][13][14][15]

Pharmacokinetics

Fulvestrant is slowly absorbed and maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) are reached after about 5 days and the terminal half-life is around 50 days. Fulvestrant is highly (99%) bound to plasma proteins including very low density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, and high density lipoprotein. It appears to be metabolized along the same pathways as endogenous steroids; CYP3A4 may be involved, but non-cytochrome routes appear to be more important. It does not inhibit any CYP450 enzymes. Elimination is almost all via feces.[10]

Fulvestrant does not cross the blood–brain barrier in animals and may not in humans as well.[16][17][18] Accordingly, no effects of fulvestrant on brain function have been observed in preclinical or clinical research.[17][18]

Chemistry

Fulvestrant is a synthetic estrane steroid and a derivative of estradiol. An alkyl-sulfinyl moiety was added to the endogenous estrogen receptor ligand.[4]

It was discovered through rational drug design, but was selected for further development via phenotypic screening.[19]

History

Fulvestrant was the first selective estrogen receptor degrader to be approved.[4] It was approved in the United States in 2002[2] and in Europe in 2004.[10]

Society and culture

NICE evaluation

The U.K. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) said in 2011 that it found no evidence Faslodex was significantly better than existing treatments, so its widespread use would not be a good use of resources for the country's National Health Service. The first month's treatment of Faslodex, which starts with a loading dose, costs £1,044.82 ($1,666), and subsequent treatments cost £522.41 a month. In the 12 months ending June 2015, the UK price (excluding VAT) of a month's supply of anastrozole (Arimidex), which is off patent, cost 89 pence/day, and letrozole (Femara) cost £1.40/day.[20][21][22]

Patent extension

The original patent for Faslodex expired in October 2004. Drugs subject to pre-marketing regulatory review are eligible for patent extension, and for this reason AstraZeneca got an extension of the patent to December 2011.[23][24] AstraZeneca has filed later patents. A generic version of Faslodex has been approved by the FDA. However, this does not mean that the product will necessarily be commercially available - possibly because of drug patents and/or drug exclusivity.[25] A later patent for Faslodex expires in January 2021.[26] Atossa Genetics has a patent for the administration of fulvestrant into the breast via a microcatheter invented by Susan Love.[27]

Research

Fulvestrant was studied in endometrial cancer but results were not promising and as of 2016 development for this use was abandoned.[28]

Because fulvestrant cannot be given orally, efforts have been made to develop SERD drugs that can be taken by mouth, including brilanestrant and elacestrant.[4] The clinical success of fulvestrant also led to efforts to discover and develop a parallel drug class of selective androgen receptor degraders (SARDs).[4]

References

- Dörwald FZ (4 February 2013). Lead Optimization for Medicinal Chemists: Pharmacokinetic Properties of Functional Groups and Organic Compounds. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 486–. ISBN 978-3-527-64565-7.

- "US Label: Fulvestrant" (PDF). FDA. July 2016.

- Lee CI, Goodwin A, Wilcken N (January 2017). "Fulvestrant for hormone-sensitive metastatic breast cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD011093. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011093.pub2. PMC 6464820. PMID 28043088.

- Lai AC, Crews CM (February 2017). "Induced protein degradation: an emerging drug discovery paradigm". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 16 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1038/nrd.2016.211. PMC 5684876. PMID 27885283.

- "Fulvestrant". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Estradiol immunoassays – interference from the drug fulvestrant (Faslodex®) may cause falsely elevated estradiol results Medical safety alert - GOV.UK". UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 24 March 2016.

- Fuqua JS (June 2013). "Treatment and outcomes of precocious puberty: an update". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 98 (6): 2198–207. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-1024. PMID 23515450.

- Zacharin M (May 2019). "Disorders of Puberty: Pharmacotherapeutic Strategies for Management". Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. doi:10.1007/164_2019_208. PMID 31144045.

- Sims EK, Garnett S, Guzman F, Paris F, Sultan C, Eugster EA (September 2012). "Fulvestrant treatment of precocious puberty in girls with McCune-Albright syndrome". International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology. 2012 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/1687-9856-2012-26. PMC 3488024. PMID 22999294.

- "Faslodex 250 mg solution for injection - Summary of Product Characteristics". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. 21 July 2016.

- Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB (July 2015). "International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCVII. G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor and Its Pharmacologic Modulators". Pharmacol. Rev. 67 (3): 505–40. doi:10.1124/pr.114.009712. PMC 4485017. PMID 26023144.

- Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J (February 2005). "Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells". Endocrinology. 146 (2): 624–32. doi:10.1210/en.2004-1064. PMID 15539556.

- Prossnitz ER, Barton M (August 2011). "The G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER in health and disease". Nat Rev Endocrinol. 7 (12): 715–26. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2011.122. PMC 3474542. PMID 21844907.

- Prossnitz ER, Barton M (May 2014). "Estrogen biology: new insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 389 (1–2): 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. PMC 4040308. PMID 24530924.

- Barton M (August 2012). "Position paper: The membrane estrogen receptor GPER--Clues and questions". Steroids. 77 (10): 935–42. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2012.04.001. PMID 22521564.

- Robertson JF (November 2001). "ICI 182,780 (Fulvestrant)--the first oestrogen receptor down-regulator--current clinical data". Br. J. Cancer. 85 Suppl 2: 11–4. doi:10.1054/bjoc.2001.1982. PMC 2375169. PMID 11900210.

- Howell A, Abram P (2005). "Clinical development of fulvestrant ("Faslodex")". Cancer Treat. Rev. 31 Suppl 2: S3–9. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.08.010. PMID 16198055.

- Bundred N, Howell A (April 2002). "Fulvestrant (Faslodex): current status in the therapy of breast cancer". Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2 (2): 151–60. doi:10.1586/14737140.2.2.151. PMID 12113237.

- Moffat JG, Rudolph J, Bailey D (August 2014). "Phenotypic screening in cancer drug discovery - past, present and future". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 13 (8): 588–602. doi:10.1038/nrd4366. PMID 25033736.

- UK Department of Health Commercial Medicines Unit Electronic Medicines Information Tool, London, 2015

- UK’s NICE says no to AstraZeneca breast cancer drug Faslodex, The Pharma Letter, 10 November 2011

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guidance Archived 2011-04-03 at the Wayback Machine Breast cancer (metastatic) - fulvestrant

- Patent Term Extensions The United States Patent and Trademark Office.

- Determination of Regulatory Review Period for Purposes of Patent Extension; FASLODEX A Notice by the Food and Drug Administration on 04/17/2003

- Generic Faslodex Availability, Drugs.COM

- Pink Ribbon Blues: How Breast Cancer Culture Undermines Women's Health By Gayle A. Sulik, Oxford University Press (Oct. 2010)

- US granted 6638727, Hung DT, Love S, "Methods for identifying treating or monitoring asymptomatic patients for risk reduction or therapeutic treatment of breast cancer", issued 28 October 2003, assigned to Cytyc Health Corp

- Battista MJ, Schmidt M (2016). "Fulvestrant for the treatment of endometrial cancer". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 25 (4): 475–83. doi:10.1517/13543784.2016.1154532. PMID 26882357.