Dunkirk

Dunkirk (UK: /dʌnˈkɜːrk/, US: /ˈdʌnkɜːrk/;[2][3] French: Dunkerque [dœ̃kɛʁk] (![]()

![]()

Dunkirk | |

|---|---|

Subprefecture and commune | |

Dunkirk Town Hall and port | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

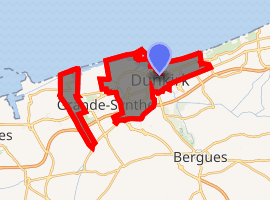

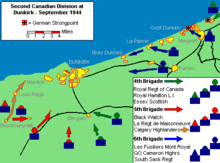

Location of Dunkirk

| |

Dunkirk  Dunkirk | |

| Coordinates: 51°02′18″N 2°22′39″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Hauts-de-France |

| Department | Nord |

| Arrondissement | Dunkerque |

| Canton | Dunkerque-1 Dunkerque-2 Grande-Synthe |

| Intercommunality | Dunkerque |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2014–2020) | Patrice Vergriete |

| Area 1 | 43.89 km2 (16.95 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 87,353 |

| • Density | 2,000/km2 (5,200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 59183 /59140, 59240, 59640 |

| Elevation | 0–17 m (0–56 ft) (avg. 4 m or 13 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Etymology and language use

The name of Dunkirk derives from West Flemish dun(e) 'dune' or 'dun' and kerke 'church', which together means 'church in the dunes'.[4]

Until the middle of the 20th century, French Flemish (the local variety of the Dutch language) was commonly spoken in Dunkirk; it has largely been forsaken, although it can still be heard.

History

Middle Ages

A fishing village arose late in the tenth century, in the originally flooded coastal area of the English Channel south of the Western Scheldt, when the area was held by the Counts of Flanders, vassals of the French Crown. About AD 960, Count Baldwin III had a town wall erected in order to protect the settlement against Viking raids. The surrounding wetlands were drained and cultivated by the monks of nearby Bergues Abbey. The name Dunkirka was first mentioned in a tithe privilege of 27 May 1067, issued by Count Baldwin V of Flanders. Count Philip I (1157–1191) brought further large tracts of marshland under cultivation, laid out the first plans to build a Canal from Dunkirk to Bergues and vested the Dunkirkers with market rights.

In the late 13th century, when the Dampierre count Guy of Flanders entered into the Franco-Flemish War against his suzerain King Philippe IV of France, the citizens of Dunkirk sided with the French against their count, who at first was defeated at the 1297 Battle of Furnes, but reached de facto autonomy upon the victorious Battle of the Golden Spurs five years later and exacted vengeance. Guy's son, Count Robert III (1305–1322), nevertheless granted further city rights to Dunkirk; his successor Count Louis I (1322–1346) had to face the Peasant revolt of 1323–1328, which was crushed by King Philippe VI of France at the 1328 Battle of Cassel, whereafter the Dunkirkers again were affected by the repressive measures of the French king.

Count Louis remained a loyal vassal of the French king upon the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War with England in 1337, and prohibited the maritime trade, which led to another revolt by the Dunkirk citizens. After the count had been killed in the 1346 Battle of Crécy, his son and successor Count Louis II of Flanders (1346–1384) signed a truce with the English; the trade again flourished and the port was significantly enlarged. However, in the course of the Western Schism from 1378, English supporters of Pope Urban VI (the Roman claimant) disembarked at Dunkirk, captured the city and flooded the surrounding estates. They were ejected by King Charles VI of France, but left great devastations in and around the town.

Upon the extinction of the Counts of Flanders with the death of Louis II in 1384, Flanders was acquired by the Burgundian, Duke Philip the Bold. The fortifications were again enlarged, including the construction of a belfry daymark (a navigational aid similar to a non-illuminated lighthouse). As a strategic point, Dunkirk has always been exposed to political greed, by Duke Robert I of Bar in 1395, by Louis de Luxembourg in 1435 and finally by the Austrian archduke Maximilian I of Habsburg, who in 1477 married Mary of Burgundy, sole heiress of late Duke Charles the Bold. As Maximilian was the son of Emperor Frederick III, all Flanders was immediately seized by King Louis XI of France. However, the archduke defeated the French troops in 1479 at the Battle of Guinegate. When Mary died in 1482, Maximilian retained Flanders according to the terms of the 1482 Treaty of Arras. Dunkirk, along with the rest of Flanders, was incorporated into the Habsburg Netherlands and upon the 1581 secession of the Seven United Netherlands, remained part of the Southern Netherlands, which were held by Habsburg Spain (Spanish Netherlands) as Imperial fiefs.

Corsair base

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The area remained much disputed between the Kingdom of Spain, the United Netherlands, the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of France. At the beginning of the Eighty Years' War, Dunkirk was briefly in the hands of the Dutch rebels, from 1577. Spanish forces under Duke Alexander Farnese of Parma re-established Spanish rule in 1583 and it became a base for the notorious Dunkirkers. The Dunkirkers briefly lost their home port when the city was conquered by the French in 1646 but Spanish forces recaptured the city in 1652. In 1658, as a result of the long war between France and Spain, it was captured after a siege by Franco-English forces following the battle of the Dunes. The city along with Fort-Mardyck was awarded to England in the peace the following year as agreed in the Franco-English alliance against Spain. The English governors were Sir William Lockhart (1658–60), Sir Edward Harley (1660–61) and Lord Rutherford (1661–62).

It came under French rule when King Charles II of England sold it to France for £320,000[5] on 17 October 1662. The French government developed the town as a fortified port. The town's existing defences were adapted to create ten bastions. The port was expanded in the 1670s by the construction of a basin that could hold up to thirty warships with a double lock system to maintain water levels at low tide. The basin was linked to the sea by a channel dug through coastal sandbanks secured by two jetties. This work was completed by 1678. The jetties were defended a few years later by the construction of five forts, Château d'Espérance, Château Vert, Grand Risban, Château Gaillard, and Fort de Revers. An additional fort was built in 1701 called Fort Blanc. The jetties, their forts, and the port facilities were demolished in 1713 under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht.[6]

During the reign of King Louis XIV, a large number of commerce raiders and pirates once again made their base at Dunkirk. Jean Bart was the most famous. The main character (and possible real prisoner) in the famous novel Man in the Iron Mask by Alexandre Dumas was arrested at Dunkirk. The eighteenth-century Swedish privateers and pirates Lars Gathenhielm and his wife Ingela Hammar, are known to have sold their gains in Dunkirk. The Treaty of Paris (1763) between France and Great Britain ending the Seven Years' War, included a clause restricting French rights to fortify Dunkirk, to allay British fears of it being used as an invasion base to cross the English Channel. This clause was overturned in the subsequent Treaty of Versailles of 1783.[7]

Dunkirk in World War I

Dunkirk's port was used extensively during the war by British forces who brought in dock workers from, among other places, Egypt and China.[8]

From 1915, the city experienced severe bombardment, including from the largest gun in the world in 1917, the German 'Lange Max'. On a regular basis, heavy shells weighing approximately 750 kg were fired from Koekelare, about 45–50 km away.[9] The bombardment killed nearly 600 people and wounded another 1,100, both civilian and military, while 400 buildings were destroyed and 2,400 damaged. The city's population, which had been 39,000 in 1914, reduced to fewer than 15,000 in July 1916 and 7,000 in the autumn of 1917.[8]

In January, 1916, a spy scare took place in Dunkirk. The writer Robert W. Service, then a war correspondent for the Toronto Star, was mistakenly arrested as a spy and narrowly avoided being executed out of hand.[10] On 1 January 1918, the United States Navy established a naval air station to operate seaplanes. The base closed shortly after the Armistice of 11 November 1918.[11]

In October 1917, to mark the gallant behaviour of its inhabitants during the war, the City of Dunkirk was awarded the Croix de Guerre and, in 1919, the Legion of Honour and the British Distinguished Service Cross.[8][12] These decorations now appear in the city's coat of arms.[13]

Dunkirk in World War II

Evacuation

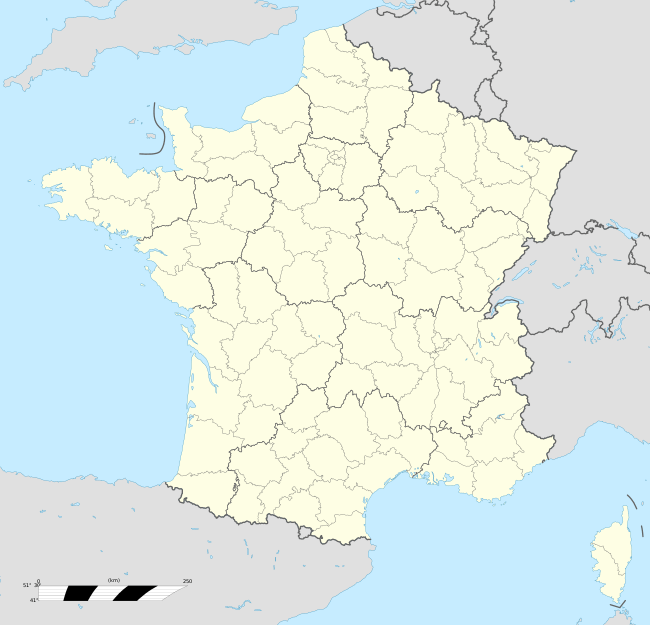

During the Second World War, in the May 1940 Battle of France, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), while aiding the French and Belgian armies, were forced to retreat in the face of the overpowering German Panzer attacks. Fighting in Belgium and France, the BEF and a portion of the French Army became outflanked by the Germans and retreated to the area around the port of Dunkirk. More than 400,000 soldiers were trapped in the pocket as the German Army closed in for the kill. Unexpectedly, the German Panzer attack halted for several days at a critical juncture. For years, it was assumed that Adolf Hitler ordered the German Army to suspend the attack, favouring bombardment by the Luftwaffe. However, according to the Official War Diary of Army Group A, its commander, Generaloberst Gerd von Rundstedt, ordered the halt to allow maintenance on his tanks, half of which were out of service, and to protect his flanks which were exposed and, he thought, vulnerable.[14] Hitler merely validated the order several hours later.[15] This lull gave the British and French a few days to fortify their defences. The Allied position was complicated by Belgian King Leopold III's surrender on 27 May, which was postponed until 28 May. The gap left by the Belgian Army stretched from Ypres to Dixmude. Nevertheless, a collapse was prevented and evacuate by sea across the English Channel, codenamed Operation Dynamo. Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, ordered any ship or boat available, large or small, to collect the stranded soldiers. 338,226 men (including 123,000 French soldiers) were evacuated – the miracle of Dunkirk, as Churchill called it. It took over 900 vessels to evacuate the BEF, with two-thirds of those rescued embarking via the harbour, and over 100,000 taken off the beaches. More than 40,000 vehicles as well as massive amounts of other military equipment and supplies were left behind, their value being regarded as less than that of trained fighting men. Forty thousand Allied soldiers (some who carried on fighting after the official evacuation) were captured or forced to make their own way home through a variety of routes including via neutral Spain. Many wounded who were unable to walk were abandoned.

Liberation

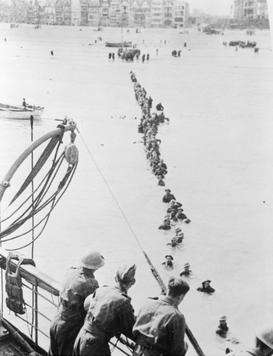

Dunkirk was again contested in 1944, with the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division attempting to liberate the city in September, as Allied forces surged northeast after their victory in the Battle of Normandy. However, German forces refused to relinquish their control of the city, which had been converted into a fortress. To seize the now strategically insignificant town would consume too many Allied resources which were needed elsewhere. The town was by-passed masking the German garrison with Allied troops, notably 1st Czechoslovak Armoured Brigade. During the German occupation, Dunkirk was largely destroyed by Allied bombing. The artillery siege of Dunkirk was directed on the final day of the war by pilots from No. 652 Squadron RAF, and No. 665 Squadron RCAF. The fortress, under the command of German Admiral Friedrich Frisius, eventually unconditionally surrendered to the commander of the Czechoslovak forces, Brigade General Alois Liška, on 9 May 1945.[16]

Postwar Dunkirk

On 14 December 2002, the Norwegian auto carrier Tricolor collided with the Bahamian-registered Kariba and sank off Dunkirk Harbour, causing a hazard to navigation in the English Channel.[17]

Politics

Presidential elections 2nd round

| Election | Candidate | Party | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Emmanuel Macron | En Marche! | 54.42 | |

| 2012 | François Hollande | PS | 55.37 | |

| 2007 | Nicolas Sarkozy | UMP | 52.30 | |

| 2002 | Jacques Chirac | RPR | 79.16 | |

Heraldry

2.svg.png) Arms of Dunkirk |

The arms of Dunkirk are blazoned: Per fess Or and argent, a lion passant sable armed and langued gules, and a dolphin naiant azure crested, barbed, finned and tailed gules. At their base, the arms display the insignia of the four medals awarded to the city: the Legion of Honour, Croix de Guerre and British Distinguished Service Cross for World War I; and a second Croix de Guerre for World War II.[13] The city also has its own flag, made up of six horizontal stripes of alternate white and azure blue.[13] |

Full achievement of the arms of Dunkirk |

Administration

The commune has grown substantially by absorbing several neighbouring communes:

- 1970: Merger with Malo-les-Bains (which had been created by being detached from Dunkirk in 1881)

- 1972: Fusion with Petite-Synthe and Rosendaël (the latter had been created by being detached from Téteghem in 1856)

- 1980: Fusion-association with Mardyck (which became an associated commune, with a population of 372 in 1999)

- 1980: A large part of Petite-Synthe is detached from Dunkirk and included into Grande-Synthe

- 2010: After a failed fusion-association attempt with Saint-Pol-sur-Mer and Fort-Mardyck in 2003, both successfully become associated communes with Dunkirk in December 2010.

Economy

Dunkirk has the third-largest harbour in France, after those of Le Havre and Marseille.[19] As an industrial city, it depends heavily on the steel, food processing, oil-refining, ship-building and chemical industries.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Dunkirk closely resembles Flemish cuisine; perhaps one of the best known dishes is coq à la bière – chicken in a creamy beer sauce.

Prototype metre

In June 1792 the French astronomers Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre and Pierre François André Méchain set out to measure the meridian arc distance from Dunkirk to Barcelona, two cities lying on approximately the same longitude as each other and also the longitude through Paris. The belfry was chosen as the reference point in Dunkirk.

Using this measurement and the latitudes of the two cities they could calculate the distance between the North Pole and the Equator in classical French units of length and hence produce the first prototype metre which was defined as being one ten millionth of that distance.[20] The definitive metre bar, manufactured from platinum, was presented to the French legislative assembly on 22 June 1799.

Dunkirk was the most easterly cross-channel measuring point for the Anglo-French Survey (1784–1790), which used trigonometry to calculate the precise distance between the Paris Observatory and the Royal Greenwich Observatory. Sightings were made of signal lights at Dover Castle from the Dunkirk Belfry, and vice versa.

Tourist attractions

- The Musée Portuaire displays exhibits of images about the history and presence of the port.

- The Musée des Beaux-Arts has a large collection of Flemish, Italian and French paintings and sculptures.

- The Carnival of Dunkirk

The Tour du Leughenaer (Tour du Leughenaer) (the Liar's Tower)

The Tour du Leughenaer (Tour du Leughenaer) (the Liar's Tower) Dunkirk Town Hall

Dunkirk Town Hall Carnival in Dunkirk

Carnival in Dunkirk Malo-les-Bains beach front

Malo-les-Bains beach front.jpg) Dunkirk Beach

Dunkirk Beach The remains of the East Mole of Dunkirk harbour, pictured in 2009

The remains of the East Mole of Dunkirk harbour, pictured in 2009

Transport

Dunkirk has a ferry with the firm DFDS with regular services each day to England. The Gare de Dunkerque railway station offers connections to Gare de Calais-Ville, Gare de Lille Flandres, Arras and Paris, and several regional destinations in France. The railway line from Dunkirk to De Panne and Adinkerke, Belgium, is closed and has been dismantled in places.

In September 2018, Dunkirk's public transit service introduced free public transport, thereby becoming the largest city in Europe to do so. Several weeks after the scheme had been introduced, the city's mayor, Patrice Vergriete, reported that there had been 50% increase in passenger numbers on some routes, and up to 85% on others. As part of the transition towards offering free bus services, the city's fleet was expanded from 100 to 140 buses, including new vehicles which run on natural gas.[21] As of August 2019, approximately 5% of 2000 people surveyed had used the free bus service to completely replace their cars.[22]

Sports

- USL Dunkerque, French football club, currently playing in the National.

- The Four Days of Dunkirk (or Quatre Jours de Dunkerque) is an important elite professional road bicycle racing event.

- Stage 2 of the 2007 Tour de France departed from Dunkirk.

Notable residents

- Jean Bart, naval commander and privateer

- Eugène Chigot, 19th -century post impressionist painter

- Marvin Gakpa, footballer

- Louise Lavoye, 19th-century soprano

- Robert Malm, footballer

- Jean-Paul Rouve, actor

- François Rozenthal, ice hockey player

- Maurice Rozenthal, ice hockey player

- Djoumin Sangaré, footballer

- Tancrède Vallerey, writer

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Dunkirk is twinned with:[23]

Climate

Dunkirk has an oceanic climate, with cool winters and warm summers. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Dunkirk has a marine west coast climate, abbreviated "Cfb" on climate maps.[25] Summers are averaging around 21 °C (70 °F), being significantly influenced by the marine currents.

| Climate data for Dunkirk (1981–2010 averages, records 1917–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.4 (83.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.4 (93.9) |

41.3 (106.3) |

36.2 (97.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

20.1 (68.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

41.3 (106.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

5.1 (41.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

2.9 (37.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.4 (7.9) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 55.0 (2.17) |

41.2 (1.62) |

46.9 (1.85) |

43.2 (1.70) |

50.4 (1.98) |

56.5 (2.22) |

58.4 (2.30) |

59.3 (2.33) |

67.0 (2.64) |

78.0 (3.07) |

74.8 (2.94) |

67.1 (2.64) |

697.8 (27.47) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.4 | 8.9 | 10.1 | 8.9 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 12.0 | 121.6 |

| Average snowy days | 2.9 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 11.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 84 | 81 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 81 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 81.8 |

| Source 1: Météo France,[26] Infoclimat.fr (humidity and snowy days, 1961–1990)[27] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [28][29] | |||||||||||||

References

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- Pul, Paul Van (2007). In Flanders Flooded Fields: Before Ypres There Was Yser. Pen and Sword. p. 89. ISBN 978-1473814318.

The French name of Dunkerque in fact is derived from the Flemish Duinkerke, which means 'church in the dunes'!

- "Correspondence and papers of the first Duke of Ormonde, chiefly on Irish and English public affairs: ref. MS. Carte 218, fol(s). 5 – date: 26 December 1662" (Description of contents of carte papers). Oxford University, Bodleian Library, Special Collections and Western Manuscripts: Carte Papers. 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "> 3D > Dunkirk Sea Forts". Fortified Places. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Ward, Sir Adolphus William (1922). "1783–1815".

- "La Grande Guerre (fr)". Dunkerque & vous. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- "Lange Max Museum".

- "Robert Service biography". robertwservice.com. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- Van Wyen, Adrian O. (1969). Naval Aviation in World War I. Washington, D.C.: Chief of Naval Operations. p. 60.

- "Traces of War". TracesOfWar. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- "Les Armoiries de la Ville (fr)". Dunkerque & vous. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- Levine, Joshua (2017) Dunkirk, Harper Collins, New York

- Lord, Walter (1982). "2: No. 17 Turns Up". The Miracle of Dunkirk. New York City: Open Road Integrated Media, Inc. pp. 28–35. ISBN 978-1-5040-4754-8.

- (in Czech) Czech army page Archived 2007-12-02 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.professionalmariner.com/March-2008/The-Tricolor-Kariba-Clary-Incident/

- http://www.lemonde.fr/nord-pas-de-calais-picardie/nord,59/dunkerque,59183/elections/presidentielle-2002/

- http://www.worldshipping.org/about-the-industry/global-trade/ports World Port Rankings 2015

- Adler, Ken (2002). The measure of all things: The seven year odyssey that transformed the world. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11507-8.

- Willsher, Kim (15 October 2018). "'I leave the car at home': how free buses are revolutionising one French city". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "French city of Dunkirk tests out free transport – and it works". France24. 31 August 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "Jumelage". ville-dunkerque.fr (in French). Dunkirk. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "Dunkirk International" (in French). Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- "Dunkerque, France Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Dunkerque (59)" (PDF). Fiche Climatologique: Statistiques 1981–2010 et records (in French). Météo-France. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- "Normes et records 1961–1990: Dunkerque (59) – altitude 11m" (in French). Infoclimat. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- "Meteo 59–62". Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- "Canicule : la France a connu hier une chaleur record au niveau national". www.meteofrance.fr (in French). Météo-France. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dunkerque. |

| Look up Dunkirk in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- City council website (in French)

- Tourist office website