Man in the Iron Mask

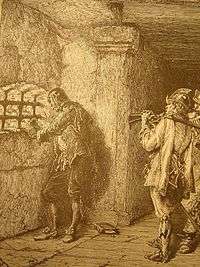

The Man in the Iron Mask (French: L'Homme au Masque de Fer; c. 1640 – 19 November 1703) was an unidentified prisoner who was arrested in 1669 or 1670 and subsequently held in a number of French prisons, including the Bastille and the Fortress of Pignerol (modern Pinerolo, Italy). He was held in the custody of the same jailer, Bénigne Dauvergne de Saint-Mars, for a period of 34 years. He died on 19 November 1703 under the name Marchioly, during the reign of King Louis XIV of France (1643–1715).

Man in the Iron Mask | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Birth name unknown c. 1640 |

| Died | 19 November 1703 Bastille, Paris |

| Resting place | Saint-Paul Cemetery, Paris |

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | Marchioly, Eustache Dauger |

| Known for | Mystery regarding his identity |

| Criminal status | Died in prison |

| Criminal charge | Unknown |

| Penalty | Life imprisonment |

Date apprehended | 1669/70 |

No one is known to have seen his face because it was hidden by a mask of black velvet cloth, and the true identity of the prisoner remains a mystery; it has been extensively debated by historians, and various theories have been expounded in numerous books and films.

Among the leading theories is that proposed by the writer and philosopher Voltaire, who claimed in the second edition of his Questions sur l'Encyclopédie (1771) that the prisoner wore a mask made of iron rather than of cloth, and that he was the older, illegitimate brother of Louis XIV. What little is known about the historical Man in the Iron Mask is based mainly on correspondence between Saint-Mars and his superiors in Paris. Recent research suggests that his name might have been Eustache Dauger, a man who was involved in several political scandals of the late 17th century, but this assertion has not been proven.

The National Archives of France has made the original data available online relating to the inventories of the goods and papers of Saint-Mars (one inventory, of 64 pages, was drawn up at the Bastille in 1708; the other, of 68 pages, at the citadel of Sainte-Marguerite in 1691). These documents had been sought in vain for more than a century and were thought to have been lost. They were discovered in 2015, among the 100 million documents of the Minutier central des notaires de Paris.[1][2] They show that some of the 800 documents in the possession of the jailer Saint-Mars were analysed after his death. These documents confirm the reputed avarice of Saint-Mars, who appears to have diverted the funds paid by the king for the prisoner. They also give a description of a cell occupied by the masked prisoner, which contained only a sleeping mat, but no luxuries, as was previously thought.

The Man in the Iron Mask has also appeared in many works of fiction, most prominently in the late 1840s by Alexandre Dumas. A section of his novel The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later, the final installment of his D'Artagnan saga, features the Man in the Iron Mask. Here the prisoner is forced to wear an iron mask and is portrayed as Louis XIV's identical twin.[3] Dumas also presented a review of the popular theories about the prisoner extant in his time in the chapter "L'homme au masque de fer" in the sixth volume of his non-fiction Crimes Célèbres.[4]

Prisoner

Arrest and imprisonment

The earliest surviving records of the masked prisoner are from late July 1669, when Louis XIV's minister, the Marquis de Louvois, sent a letter to Bénigne Dauvergne de Saint-Mars, governor of the prison of Pignerol (which at the time was part of France). In his letter, Louvois informed Saint-Mars that a prisoner named "Eustache Dauger" was due to arrive in the next month or so.

Louis XIV instructed Saint-Mars to prepare a cell with multiple doors, one closing upon the other, which were to prevent anyone from the outside listening in. Saint-Mars was to see Dauger only once a day to provide food and whatever else he needed. Dauger was to be told that if he, Dauger, spoke of anything other than his immediate needs he would be killed, but, according to Louvois, the prisoner should not require much since he was "only a valet".

Historians have noted that the name Eustache Dauger was written in a handwriting different from that used in the rest of the letter's text, suggesting that a clerk wrote the letter under Louvois' dictation, while someone else, very likely Louvois, added the name afterward.

Dauger was arrested by Captain Alexandre de Vauroy, garrison commander of Dunkirk, and taken to Pignerol, where he arrived in late August. Evidence has been produced to suggest that the arrest was actually made in Calais and that not even the local governor was informed of the event – Vauroy's absence being explained away by his hunting for Spanish soldiers who had strayed into France via the Spanish Netherlands.[5]

The first rumours of the prisoner's identity (specifically as a Marshal of France) began to circulate at this point.

Masked man serves as a valet

The prison at Pignerol, like the others at which Dauger was later held, was used for men who were considered an embarrassment to the state and usually held only a handful of prisoners at a time.

Saint-Mars' other prisoners at Pignerol included Count Ercole Antonio Mattioli, an Italian diplomat who had been kidnapped and jailed for double-crossing the French over the purchase of the important fortress town of Casale on the Italian border. There was Nicolas Fouquet, Marquis of Belle-Île, a former superintendent of finances who had been jailed by Louis XIV on the charge of embezzlement, and the Marquis de Lauzun, who had become engaged to the Duchess of Montpensier, a cousin of the king, without the king's consent. Fouquet's cell was above that of Lauzun.

In his letters to Louvois, Saint-Mars describes Dauger as a quiet man, giving no trouble, "disposed to the will of God and to the king", compared to his other prisoners, who were always complaining, constantly trying to escape, or simply mad.[5]

Dauger was not always isolated from the other prisoners. Wealthy and important ones usually had manservants; Fouquet for instance was served by a man called La Rivière. These servants, however, would become as much prisoners as their masters and it was thus difficult to find people willing to volunteer for such an occupation. Because La Rivière was often ill, Saint-Mars applied for permission for Dauger to act as servant for Fouquet. In 1675, Louvois gave permission for such an arrangement on condition that he was to serve Fouquet only while La Rivière was unavailable and that he was not to meet anyone else; for instance, if Fouquet and Lauzun were to meet, Dauger was not to be present.

It is an important point that the man in the mask served as a valet. Fouquet was never expected to be released; thus, meeting Dauger was no great matter, but Lauzun was expected to be set free eventually, and it would have been important not to have him spread rumours of Dauger's existence or of secrets he might have known. Historians have also argued that 17th-century protocol made it unthinkable that a man of royal blood would serve as a manservant, casting some doubt on speculation that Dauger was in some way related to the king.[3]

After Fouquet's death in 1680, Saint-Mars discovered a secret hole between Fouquet and Lauzun's cells. He was sure that they had communicated through this hole without detection by him or his guards and thus that Lauzun must have been made aware of Dauger's existence. Louvois instructed Saint-Mars to move Lauzun to Fouquet's cell and to tell him that Dauger and La Rivière had been released.

Other prisons

Lauzun was freed in 1681. Later that same year, Saint-Mars was appointed governor of the prison of the Exiles Fort (now Exilles in Italy). He went there, taking Dauger and La Rivière with him. La Rivière's death was reported in January 1687; in May, Saint-Mars and Dauger moved to Sainte-Marguerite, one of the Lérins Islands, half a mile offshore from Cannes.

It was during the journey to Sainte-Marguerite that rumors spread that the prisoner was wearing an iron mask. Again, he was placed in a cell with multiple doors.

On 18 September 1698, Saint-Mars took up his new post as governor of the Bastille prison in Paris, bringing Dauger with him. He was placed in a solitary cell in the prefurnished third chamber of the Bertaudière tower. The prison's second-in-command, de Rosarges, was to feed him. Lieutenant du Junca, another officer of the Bastille, noted that the prisoner wore "a mask of black velvet".

The masked prisoner died on 19 November 1703 and was buried the next day under the name of Marchioly.

In 1711, King Louis's sister-in-law, Elizabeth Charlotte, Princess Palatine, sent a letter to her aunt, Sophia, Electress of Hanover, stating that the prisoner had "two musketeers at his side to kill him if he removed his mask". She described him as very devout, and stated that he was well treated and received everything he desired. However, the prisoner had already been dead for eight years by that point and the Princess had not necessarily seen him for herself; rather, she was quite likely reporting rumours she had heard at court.

Popular interest

The fate of the mysterious prisoner – and the extent of the apparent precautions his jailers took – created significant interest in his story and gave birth to many legends. Many theories exist and several books have been written about the case. Some were presented after the existence of the letters was widely known. Still later commentators have presented their own theories, possibly based on embellished versions of the original tale.

Theories about his identity that were popular during his time included that he was a Marshal of France; the English Henry Cromwell,[6] son of Oliver Cromwell; or François, Duke of Beaufort. Later, many people such as Voltaire and Alexandre Dumas[7] suggested other theories about the man in the mask.

Candidates

King's relative

Voltaire claimed that the prisoner was a son of Anne of Austria and Cardinal Mazarin, and therefore an illegitimate half-brother of King Louis XIV. However, the sincerity of this claim is uncertain.

King's twin brother

In a 1965 essay Le Masque de fer,[8] French novelist Marcel Pagnol, supporting his theory in particular on the circumstances of King Louis XIV's birth, claims that the Man in the Iron mask was indeed a twin but born second, and hence the younger, and would have been hidden in order to avoid any dispute over the throne holder.[8] [lower-alpha 1]

The historians who reject this theory (including Jean-Christian Petitfils), highlight the conditions of childbirth for the queen: It usually took place in the presence of multiple witnesses – the main court's figures. But according to Marcel Pagnol, immediately after the birth of the future Louis XIV, King Louis XIII took his whole court to the Château de Saint-Germain's chapel to celebrate a Te Deum in great pomp, contrary to the common practice of celebrating it several days before childbirth.[9]

Aligned with the theory of King Louis XIV having had a twin, a thorough examination of the French Kings' genealogy shows many twin births, in the Capetian dynasty, as well as in the House of Valois, Bourbon, and the House of Orléans.[10]

Alexandre Dumas explored a similar theory in his book The Vicomte de Bragelonne, where the prisoner was instead an identical twin of Louis XIV. This book has served as the basis – even if loosely adapted – for many film versions of the story.

According to Marcel Pagnol's theory, this twin was then born in 1638 and grew up on the Island of Jersey under the name James de la Cloche. He would supposedly later conspire with Roux de Marcilly against King Louis XIV, and be arrested in Calais in 1669.

King's father

Hugh Ross Williamson[11] argued that the man in the iron mask was the natural father of Louis XIV. According to this theory, the "miraculous" birth of Louis XIV in 1638 would have come after Louis XIII had been estranged from his wife Anne of Austria for 14 years.

The theory then suggests that Cardinal Richelieu, the king's minister, had arranged for a substitute, probably an illegitimate son or grandson of Henry IV, to become intimate with the queen and father an heir in the king's stead. At the time, the heir presumptive was Louis XIII's brother Gaston, Duke of Orléans, who was Richelieu's enemy. If Gaston became king, Richelieu would quite likely have lost both his job as minister and his life, and so it was in his best interests to thwart Gaston's ambitions.

Supposedly the substitute father then left for the Americas but in the 1660s returned to France with the aim of extorting money for keeping his secret, and was promptly imprisoned. This theory would explain the secrecy surrounding the prisoner, whose true identity would have destroyed the legitimacy of Louis XIV's claim to the throne had it been revealed.

This theory was notably disputed by British politician Hugh Cecil, 1st Baron Quickswood. He said the idea has no historical basis and is hypothetical. Williamson held that to say it is a guess with no solid historical basis is merely to say that it is like every other theory on the matter, although it makes more sense than any of the other theories. There is no known evidence that is incompatible with it, even the age of the prisoner, which Cecil had considered a weak point; and it explains every aspect of the mystery.[11]

French general

In 1890, Louis Gendron, a French military historian, came across some coded letters and passed them on to Étienne Bazeries in the French Army's cryptographic department. After three years Bazeries managed to read some messages in the Great Cipher of Louis XIV. One of them referred to a prisoner and identified him as General Vivien de Bulonde. One of the letters written by Louvois made specific reference to de Bulonde's crime.

At the Siege of Cuneo in 1691, Bulonde was concerned about enemy troops arriving from Austria and ordered a hasty withdrawal, leaving behind his munitions and wounded men. Louis XIV was furious and in another of the letters specifically ordered him "to be conducted to the fortress at Pignerol where he will be locked in a cell and under guard at night, and permitted to walk the battlements during the day with a 330 309." It has been suggested that the 330 stood for masque and the 309 for full stop. However, in 17th-century French avec un masque would mean "in a mask".

Some believe that the evidence of the letters means that there is now little need of an alternative explanation for the man in the mask. Other sources, however, claim that Bulonde's arrest was no secret and was actually published in a newspaper at the time and that he was released after just a few months. His death is also recorded as happening in 1709, six years after that of the man in the mask.[5]

Valet

In 1801, revolutionary legislator Pierre Roux-Fazillac stated that the tale of the masked prisoner was an amalgamation of the fates of two separate prisoners, Ercole Antonio Mattioli (see below) and an imprisoned valet named "Eustache d'Auger".

Lang (1903)[12] presented a theory that "Eustache d'Auger" was a prison pseudonym of a man called "Martin", valet of the Huguenot Roux de Marcilly. After his master's execution in 1669 the valet was taken to France, possibly by abduction. A letter from the French Foreign minister has been found rejecting an offer to arrest Martin: He was simply not important.[13]

Noone (1988)[14] pointed out that the minister was concerned Dauger should not communicate, rather than that his face should be concealed. Later, St. Mars elaborated upon instructions that the prisoner should not be seen during transportation. The idea of keeping d'Auger in a velvet mask was St. Mars' own, to increase his self importance. What d'Auger had seen or done is still a mystery.

In 2016 the historian Paul Sonnino provided additional circumstantial evidence to support the idea that the valet Eustache d'Auger was the man in the mask.[15][16]

Son of Charles II

Barnes (1908)[17] presents James de la Cloche, the alleged illegitimate son of the reluctant Protestant Charles II of England, who would have been his father's secret intermediary with the Catholic court of France.

One of Charles's confirmed illegitimate sons, the Duke of Monmouth, has also been proposed as the man in the mask. A Protestant, he led a rebellion against his uncle, the Catholic King James II. The rebellion failed and Monmouth was executed in 1685. But in 1768, a writer named Saint-Foix claimed that another man was executed in his place and that Monmouth became the masked prisoner, it being in Louis XIV's interests to assist a fellow Catholic like James who would not necessarily want to kill his own nephew. Saint-Foix's case was based on unsubstantiated rumors and allegations that Monmouth's execution was faked.[5]

Italian diplomat

Another candidate, much favored in the 1800s, was Fouquet's fellow prisoner Count Ercole Antonio Mattioli (or Matthioli). He was an Italian diplomat who acted on behalf of debt-ridden Charles IV, Duke of Mantua in 1678, in selling Casale, a strategic fortified town near the border with France. A French occupation would be unpopular, so discretion was essential, but Mattioli leaked the details to France's Spanish enemies, after pocketing his commission once the sale had been concluded, and they made a bid of their own before the French forces could occupy the town. Mattioli was kidnapped by the French and thrown into nearby Pignerol in April 1679. The French took possession of Casale two years later.[5]

George Agar Ellis reached the conclusion that Mattioli was the state prisoner commonly called The Iron Mask when he reviewed documents extracted from French archives in the 1820s. His book,[18] published in English in 1826, was translated into French and published in 1830. German historian Wilhelm Broecking came to the same conclusion independently seventy years later. Robert Chambers' Book of Days supports the claim and places Matthioli in the Bastille for the last 13 years of his life.

Since that time, letters sent by Saint-Mars, which earlier historians missed, indicate that Mattioli was only held at Pignerol and Sainte-Marguerite and was not at Exilles or the Bastille and, therefore, it is argued that he can be discounted.[3]

Eustache Dauger de Cavoye

In his letter to Saint-Mars announcing the imminent arrival of the prisoner who would become the "man in the iron mask," Louvois gave his name as "Eustache Dauger" and historians have found evidence that a "Eustache Dauger" was living in France at the time and was involved in scandalous and embarrassing events involving people in high places known as l'Affaire des Poisons. His full name was Eustache Dauger de Cavoye.[5]

Early life

Records indicate that he was born on 30 August 1637, the son of François Dauger, a captain in Cardinal Richelieu's guards. François was married to Marie de Sérignan and they had 11 children, nine of whom survived into adulthood. When François and his two eldest sons were killed in battle, Eustache became the nominal head of the family.

Disgrace

In April 1659, Eustache and Guiche were invited to an Easter weekend party at the castle of Roissy-en-Brie. By all accounts it was a debauched affair of merry-making, with the men involved in all sorts of sordid activities, including attacking a man who claimed to be Cardinal Mazarin's attorney. It was also claimed, among other things, that a black mass was enacted and that a pig was baptized as carp in order to allow them to eat pork on Good Friday.

When news of these events became public, an inquiry was held and the various perpetrators jailed or exiled. There is no record as to what happened to Dauger, but in 1665, near the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, he allegedly killed a young page boy in a drunken brawl involving the Duc de Foix. The two men claimed that they had been provoked by the boy, who was drunk, but the fact that the killing took place near a castle where the king was staying meant that this was not a good enough explanation, and as a result, Dauger was forced to resign his commission.

Dauger's mother died shortly afterwards. In her will, written a year previously, she passed over her eldest surviving sons Eustache and Armand, leaving the bulk of the estate to their younger brother Louis. Eustache was restricted in the amount of money to which he had access, having built up considerable debts, and left with barely enough for "food and upkeep".

Affair of the Poisons

In the 1930s, historian Maurice Duvivier linked Eustache Dauger de Cavoye to the Affair of the Poisons, a notorious scandal of 1677–1682 in which people in high places were accused of being involved in black mass and poisonings. An investigation had been launched, but Louis XIV had instigated a cover-up when it appeared that his mistress Madame de Montespan was involved.[5]

The records show that during the inquiry the investigators were told about a supplier of poisons, a surgeon named Auger, and Duvivier became convinced that Dauger de Cavoye, disinherited and short of money, had become Auger, the supplier of poisons, and subsequently Dauger, the man in the mask.

In a letter sent by Louvois to Saint-Mars shortly after Fouquet's death while in prison (with Dauger acting as his valet), the minister adds a note in his own handwriting, asking how Dauger performed certain acts that Saint-Mars had mentioned in a previous correspondence (now lost) and "how he got the drugs necessary to do so". Duvivier suggested that Dauger may have poisoned Fouquet as part of a complex power struggle between Louvois and his rival Colbert.

Dauger in prison

However, evidence has emerged that Dauger de Cavoye actually died in the Prison Saint-Lazare, an asylum run by monks which many families used in order to imprison their "black sheep". Documents have survived indicating that Dauger de Cavoye was held at Saint-Lazare in Paris at about the same time that Dauger, the man in the mask, was taken into custody in Pignerol, hundreds of miles away in the south.

These include a letter sent to Dauger de Cavoye's sister, the Marquise de Fabrègues, dated 20 June 1678, which is filled with self-pity as Eustache complains about his treatment in prison, where he has been held for 10 years, and how he was deceived by their brother Louis and Clérac, their brother-in-law and the manager of Louis' estate. A year later, he wrote a letter to the king, outlining the same complaints and making a similar request for freedom. The best the king would do, however, was to send a letter to the head of Saint-Lazare telling him that "M. de Cavoye should have communication with no one at all, not even with his sister, unless in your presence or in the presence of one of the priests of the mission". The letter was signed by the king and Colbert.

A poem written by Louis-Henri de Loménie de Brienne, an inmate at the time, indicates that Eustache Dauger de Cavoye died as a result of heavy drinking in the late 1680s. Historians consider all this proof enough that he was not involved in any way with the man in the mask.[3][5]

In popular culture

Literature

- Alfred de Vigny, "The Prison" (1821),[19] a long poem describing the final events in the life of the Man in the Iron Mask. An aged priest is called to offer the last rites of the Catholic Church to a mysterious prisoner. After an involved process to ensure the prisoner's anonymity, the priest is introduced to the dying prisoner, who is addressed as "my prince" by the jailer. The priest realizes in the dim light that the prisoner wears an iron mask, and recalls the tales he heard in his youth. The prisoner rejects the priest's efforts, even after the priest promises that his lifelong incarceration has already opened Heaven to him if he would only embrace God. The prisoner dies without repenting. The priest continues to pray for the man for several hours, and is horrified to see that the corpse continues to wear the mask underneath the shroud, denied release even in death.

- Alexandre Dumas, The Vicomte de Bragelonne: Ten Years Later (1847–1850), the final section of which is titled The Man in the Iron Mask (French: L'homme au masque de fer)

- Henry Vizetelly, The Man With the Iron Mask (1870)

- Juliette Benzoni, Secret d'etat

- Louis-César, Cassandra Palmer series

- Algis Budrys's 1958 science-fiction novel Who? / The Man in the Steel Mask, and the 1973 film based on it, are loosely inspired by the historical affair, placing a similar mystery in a contemporary Cold War setting.

- Karleen Koen, Before Versailles, in which the boy in the iron mask is a central issue among the characters.

- Fortuné du Boisgobey, Le Vrai Masque de fer (1873). The serialized translations of this work in Japan and Korea in the early twentieth century made this the most popular “Man in the Iron Mask” in these countries, more so than the Dumas novel.

Films and television

- 1909: La maschera di ferro – Italian silent film

- 1923: Der Mann mit der eisernen Maske – German silent film

- 1929: The Iron Mask – An American silent film starring Douglas Fairbanks

- 1938: The Face Behind the Mask – An American short film directed by Jacques Tourneur

- 1939: The Man in the Iron Mask – American black and white film directed by James Whale, starring Louis Hayward, Joan Bennett, Warren William and Alan Hale Sr.

- 1952: Lady in the Iron Mask – American color film starring Louis Hayward, Patricia Medina and Alan Hale Jr.

- 1962: Le Masque de fer – Italian/French film, starring Jean Marais

- 1968: The Man in the Iron Mask – British TV series (9 episodes)

- 1968: The Three Musketeers (Animated Series) from The Banana Splits Adventure Hour – "The True King"

- 1970: Start the Revolution Without Me - Man in mask is seen in jailcell, with there linking two cells together by tunnel.

- 1977: The Man in the Iron Mask – British TV movie with Richard Chamberlain, Patrick McGoohan, Louis Jourdan, Jenny Agutter, Ian Holm, Ralph Richardson and Vivien Merchant

- 1979: The Fifth Musketeer also known as Behind the Iron Mask – Austrian/West German film directed by Ken Annakin, with Sylvia Kristel, Ursula Andress, Beau Bridges, Cornel Wilde, Lloyd Bridges, José Ferrer, Olivia de Havilland, Ian McShane, Rex Harrison and Alan Hale Jr.; remake of the 1939 film

- 1985: The Man in the Iron Mask – Australian animated TV film

- 1987: Three Musketeers – Japanese anime television series, included the character of The Man in the Iron Mask depicted as a Doctor Doom-like villain.

- 1987: DuckTales – American animated TV series, Season 1, Episode 10 "The Duck in the Iron Mask."

- 1993: The Secret of Queen Anne or Musketeers Thirty Years After – Russian musical film directed by Georgi Yungvald-Khilkevich based on Alexandre Dumas' novel The Vicomte de Bragelonne, with Mikhail Boyarsky, Veniamin Smekhov, Valentin Smirnitsky, Igor Starygin, Alisa Freindlich and Dmitry Kharatyan

- 1998: The Man in the Iron Mask – British/American film directed by Randall Wallace, with Leonardo DiCaprio, Jeremy Irons, John Malkovich, Gérard Depardieu and Gabriel Byrne

- 1998: The Man in the Iron Mask also known as The Mask of Dumas – American film, directed by William Richert, with Edward Albert, Dana Barron, Rex Ryon and Timothy Bottoms

- 2001: The Mole – The first season of the American version of The Mole had one test that took inspiration from The Man in the Iron Mask story. One contestant was kidnapped from his room and held prisoner in a jail in Monte Carlo. The contestant was forced to wear a Iron Mask while locked up.

- 2007: Revenge Is a Dish Best Served Three Times – 18th season of The Simpsons animated television program.

- 2009: G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra – James McCullen's family background is retconned as his ancestor James McCullen IX was only punished by the French monarchy after being caught selling weapons to both them and England, condemned to have a red-hot iron mask welded onto his face and serve as an example to others who attempted to overthrow the crown.

- 2014: The Musketeers (BBC 2014 adaptation) – series 1, episode 6

- 2016: The Flash (season 2), The CW TV Series – Season 2, Episode 14, The real Jay Garrick is imprisoned and locked in an iron mask by Hunter Zolomon while he impersonates him. This seems to be an homage to the fictional telling in The Man in the Iron Mask (1998 film)

- 2018: In Versailles, the Franco-Canadian TV series, the 3rd series commences with the Man in the Iron Mask imprisoned and under consideration for dispatch to the Americas.

Comic books

- 1956: "The Three Super-Musketeers" (World's Finest Comics 82), written by Edmond Hamilton, illustrated by Dick Sprang. Superman, Batman and Robin are the title characters, tasked to conceal the prisoner's identity.

- 1965: "The Phantom of Notre Duck" (Uncle Scrooge 60) by Carl Barks. Scrooge McDuck has a silly adventure in Duckburg, mashing up elements of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Phantom of the Opera and (briefly) Dumas' version of the Iron Mask legend.

Music

- 1983: "The Man in the Iron Mask" – a track on Life's a Riot with Spy vs Spy by Billy Bragg.

- 1992: "The Iron Mask" – a CD by gothic rock band Christian Death.

- 1999: "These Are the times," a music video by the R&B group Dru Hill.

- 2006: "Tilting the Hourglass" – a song released by rock band Alesana on their debut album On Frail Wings of Vanity and Wax, in which the imprisonment and feelings of the prisoner are portrayed in song.

- 2019: “The Man in The Iron Mask” - a song released by Magneto Dayo

Gaming

- 2014: In Assassin's Creed Unity, a DLC titled "Dead Kings". In "Dead Kings", player can get a new story content and an outfit of "The Man in The Iron Mask".

See also

- The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later

- Ivan VI of Russia, a prisoner with a similar story

- Look-alike

Footnotes

- To make the context clearer, note that at the time there was a controversy over which one of twins was the elder: The one born first, or the one born second, who was then thought to have been conceived first.

References

- Archives nationales de France: salle des inventaires, Archives nationales (accessed 23 January 2017).

- Analyse et photographies des documents découverts, https://sergearoles-documents-archives.com/ [archive] (accessed 23 January 2017).

- The Man in the Iron Mask, Timewatch TV documentary presented by Henry Lincoln, BBC, 1988

- "Crimes célèbres : Alexandre Dumas : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Archive.org. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- The Man Behind the Iron Mask by John Noone, 1988 ISBN 0750906790

- Dumas, Alexandre (1910). Celebrated Crimes. 6. p. 2008.

- "Gutenberg.org". Gutenberg.org. 22 September 2004. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Pagnol, Marcel (1965). Le Masque de fer. Éditions de Provence. pp. chapters 11 & 12.

- Dumont, Jean (ed.). Supplément au Corps Universel Diplomatique. IV. p. 176.

- Kermabon, Yann (October 1998). "Courrier des lecteurs". Revue Historia.

- Williamson, Hugh Ross (2002). Who Was The Man In the Iron Mask? and Other Historical Mysteries. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-139097-2.

- Lang, Andrew (1903). The Valet's Tragedy and Other Stories.

- Thompson, Harry. The Man in the Iron Mask. p. 77.

- Noone, John (1988). The Man behind the Mask. p. 272.

- https://www.livescience.com/54669-man-in-the-iron-mask-identified.html. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- https://www.ranker.com/list/the-real-man-in-the-iron-mask/. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Barnes, Arthur (1908). The Man of the Mask.

- George Agar Ellis, The true history of the State Prisoner commonly called the Iron Mask, here identified with Count E.A. Mattioli, extracted from documents in the French archives (London, J. Murray, 1826)

- "La Prison (Vigny)" (in French). Fr.wikisource.org. Retrieved 31 January 2018 – via Wikisource.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Man in the Iron Mask. |

- The Man in the Iron Mask at Project Gutenberg

- Who was the "Man in the Iron Mask"? at the Straight Dope