Cyrene, Libya

Cyrene (/saɪˈriːniː/; Ancient Greek: Κυρήνη, romanized: Kyrēnē) was an ancient Greek and later Roman city near present-day Shahhat, Libya. It was the oldest and most important of the five Greek cities in the region. It gave eastern Libya the classical name Cyrenaica that it has retained to modern times. Located nearby is the ancient Necropolis of Cyrene.

Κυρήνη | |

The ruins of Cyrene | |

Shown within Libya | |

| Location | Shahhat, Jabal al Akhdar, Cyrenaica, Libya |

|---|---|

| Region | Jebel Akhdar |

| Coordinates | 32°49′30″N 21°51′29″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Colonists from Thera led by Battus I |

| Founded | 631 BC |

| Abandoned | 4th century AD |

| Periods | Archaic Greece to Roman Empire |

| Site notes | |

| Official name | Archaeological Site of Cyrene |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1982 (6th session) |

| Reference no. | 190 |

| Region | Arab States |

Cyrene lies in a lush valley in the Jebel Akhdar uplands. The city was named after a spring, Kyre, which the Greeks consecrated to Apollo. It was also the seat of the Cyrenaics, a famous school of philosophy in the fourth century BC, founded by Aristippus, a disciple of Socrates.

History

Summary of the founding of Cyrene, as told by Herodotus

Grinus, son of Aesanius a descendant of Theras, and king of the island of Thera, had visited the Pythia, the oracle of Delphi, and offered a hecatomb to the Pythia on sundry matters. The Pythia had offered the advice to found a new city in Libya.

Many years passed and the advice was not taken, and Thera had succumbed to a horrific drought and all of the crops and trees had perished. They again sent to Delphi and were reminded that the Pythia had said several years before to settle in the country of Libya, but this time she specifically said to found a settlement in the land of Cyrene.

Not knowing how to get to Libya, they sent a messenger to Crete to find someone to lead them on their journey. They found a dealer in purple dyes named Corobius. He had once traveled to an island across from Libya called Platea [or Plataea, modern Jazirat Barda`ah].[1] Grinus and Corobius sailed to Platea, when they reached their destination they left Corobius with months of supplies and Grinus went back to Thera to collect men to settle the newly made colony. After two years of settling the colony, they had little success and went back to the Pythia to get advice. The Pythia had repeated her advice to move directly to the country of Libya instead of across from Libya. So they moved to a place called Aziris. They settled there for six years, and were very successful until the Libyans visited the settlement of Aziris to convince the people to move further inland. They were swayed by the Libyans to move and settled into what is now Cyrene. The current king of that time Battus reigned for 40 years, until he passed on and his son, Arcesilaus, took over and reigned for 16 years, with no more or less population change until the Oracle had told the third king, another Battus, to bring Greek citizens to the settlement and with that expansion the Libyans had lost a lot of land surrounding Cyrene.[2]

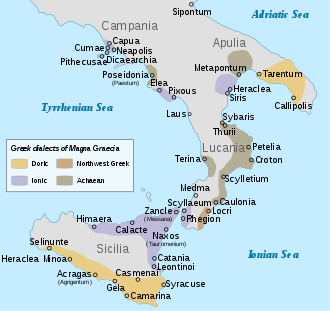

Greek period

According to Greek tradition, Cyrene was founded in 631 BC as a settlement of Greeks from the island of Thera, traditionally led by Battus I,[3] at a site 16 kilometres (10 mi) from its associated port, Apollonia (Marsa Sousa). Traditional details concerning the founding of the city are contained in Herodotus' Histories IV. Cyrene promptly became the chief town of Libya and established commercial relations with all the Greek cities, reaching the height of its prosperity under its own kings in the 5th century BC. Soon after 460 BC it became a republic. In 413 BC, during the Peloponnesian War, Cyrene supplied Spartan forces with two triremes and pilots.[4] After the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC), the Cyrenian republic became subject to the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Ophellas, the general who occupied the city in the name of Ptolemy I Soter's, ruled the city almost independently until his death, when Ptolemy's son-in-law Magas received governorship of the territory. In 276 BC Magas crowned himself king and declared de facto independence, marrying the daughter of the Seleucid emperor and forming with him an alliance in order to invade the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

The invasion was unsuccessful and in 250 BC, after Magas' death, the city was reabsorbed into Ptolemaic Egypt. Cyrenaica became part of the Ptolemaic empire controlled from Alexandria, and became Roman territory in 96 BC when Ptolemy Apion bequeathed Cyrenaica to Rome. In 74 BC the territory was formally transformed into a Roman province.

Roman period

In 74 BC Cyrene was created a Roman province; but, whereas under the Ptolemies the Jewish inhabitants had enjoyed equal rights, they were allegedly increasingly oppressed by the now autonomous and much larger Greek population. Tensions came to a head in the insurrection of the Jews of Cyrene under Vespasian (73 AD, the First Jewish–Roman War) and especially Trajan (117 AD, the Kitos War). This revolt was quelled by Marcius Turbo, but not before huge numbers of civilians had been brutally massacred by the Jewish rebels.[5] According to Eusebius of Caesarea, the Jewish rebellion left Libya so depopulated to such an extent that a few years later new colonies had to be established there by the emperor Hadrian just to maintain the viability of continued settlement.

Plutarch in his work De mulierum virtutibus ("On the Virtues of Women") describes how the tyrant of Cyrene, Nicocrates, was deposed by his wife Aretaphila of Cyrene around the year 50 BC[6]

The famous "Venus of Cyrene", a headless marble statue representing the goddess Venus, a Roman copy of a Greek original, was discovered by Italian soldiers here in 1913. It was transported to Rome, where it remained until 2008, when it was returned to Libya.[7] A large number of Roman sculptures and inscriptions were excavated at Cyrene by Captain Robert Murdoch Smith and Commander Edwin A. Porcher during the mid nineteenth century and can now be seen in the British Museum.[8] They include the Apollo of Cyrene and a unique bronze head of an African man.[9][10]

Christianity

Christianity is reputed from its beginning to have had links with Cyrene. All three synoptic Gospels mention a Simon of Cyrene as having been forced to help carry the cross of Jesus. In the Acts of the Apostles there is mention of people from Cyrene being in Jerusalem on the Day of Pentecost.[11] According to the tradition of the Coptic Orthodox Church, its founder, Saint Mark was a native of Cyrene and ordained the first bishop of Cyrene. The Roman Martyrology[12] mentions under 4 July a tradition that in the persecution of Diocletian a bishop Theodorus of Cyrene was scourged and had his tongue cut out. Earlier editions of the Martyrology mentioned what may be the same person also under 26 March. Letter 67 of Synesius tells of an irregular episcopal ordination carried out by a bishop Philo of Cyrene, which was condoned by Athanasius. The same letter mentions that a nephew of this Philo, who bore the same name, also became bishop of Cyrene. Although Cyrene was by then ruined, a bishop of Cyrene name Rufus was at the Robber Council of Ephesus in 449. And there was still a bishop of Cyrene, named Leontius, at the time of Greek Patriarch Eulogius of Alexandria (580–607).[13][14]

Known bishops of the town, then include:[15][16][17][18]

- Saint Luke by tradition

- Theodoro (fl.302)

- Filo I (fl.370 circa)

- Filo II (fl.370 circa)

- Rufo (fl.449)

- Leontius (fl.600 circa)

No longer a residential bishopric, Cyrene is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[19][20][21] The Greek Orthodox Church has also treated it as a titular see.[14]

Decline

Cyrene's chief local export through much of its early history was the medicinal herb silphium, used as an abortifacient; the herb was pictured on most Cyrenian coins. Silphium was in such demand that it was harvested to extinction;[22] this, in conjunction with commercial competition from Carthage and Alexandria, resulted in a reduction in the city's trade. Cyrene, with its port of Apollonia (Marsa Susa), remained an important urban center until the earthquake of 262, which damaged the Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephon in Cyrene. After the disaster, the emperor Claudius Gothicus restored Cyrene, naming it Claudiopolis, but the restorations were poor and precarious. Natural catastrophes and a profound economic decline dictated its death, and in 365 another particularly devastating earthquake destroyed its already meager hopes of recovery. Ammianus Marcellinus described it in the 4th century as a deserted city, and Synesius, a native of Cyrene, described it in the following century as a vast ruin at the mercy of the nomads. Ultimately, the city fell under Arab conquest in 643, by which time little was left of the opulent Roman cities of Northern Africa; the ruins of Cyrene are located near the modern village of Shahhat.

Philosophy

Cyrene contributed to the intellectual life of the Greeks, through renowned philosophers and mathematicians. Philosophy flourished at the Cyrenaican plateau, the School of Cyrene, known as Cyrenaics developed here, a minor Socratic school founded by Aristippus (perhaps the friend of Socrates, though according to some accounts a grandson of Aristippus with the same name). French Neo-Epicurean philosopher Michel Onfray has called Cyrene “a philosophical Atlantis” thanks to its huge importance in the birth and initial development of pleasure ethics.

Cyrene was the birthplace of Eratosthenes, who later went to Alexandria. Statues of philosophers, poets, and The Nine Muses, and a bust of Demosthenes were found in Cyrene.[23]

Others included, Aristippus successor and daughter Arete, Callimachus, Carneades, Ptolemais of Cyrene, and Synesius, a bishop of Ptolemais in the 4th century AD.

Biblical references

Cyrene is referred to in the deuterocanonical book 2 Maccabees. The book of 2 Maccabees itself is said by its author to be an abridgment of a five-volume work by a Hellenized Jew by the name of Jason of Cyrene who lived around 100 BC.

Cyrene is also mentioned in the New Testament. A Cyrenian named Simon carried the cross of Christ (Mark 15:21 and parallels). See also Acts 2:10 where Jews from Cyrene heard the disciples speaking in their own language in Jerusalem on the day of Pentecost; 6:9 where some Cyrenian Jews disputed with a disciple named Stephen; 11:20 tells of Jewish Christians originally from Cyrene who (along with believers from Cyprus) first preached the Gospel to non-Jews; 13:1 names Lucius of Cyrene as one of several to whom the Holy Spirit spoke, instructing them to appoint Barnabas and Saul (later Paul) for missionary service.

Present

Cyrene is now an archeological site near the village of Shahhat. One of its more significant features is the temple of Apollo see lists of temples in Libya which was originally constructed as early as 7th century BC. Other ancient structures include a temple to Demeter and a partially unexcavated temple to Zeus There is a large necropolis approximately 10 km between Cyrene and its ancient port of Apollonia. The Temple of Zeus, originally built in the 6th century BC, has been destroyed and rebuilt many times, being rebuilt in the 2nd century AD after the Jewish revolt in 115 AD and damaged during earthquakes in the 4th century AD.[24] Since 1982, it has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[25]

In 2005, Italian archaeologists from the University of Urbino discovered 76 intact Roman statues at Cyrene from the 2nd century AD. The statues remained undiscovered for so long because “during the earthquake of 375 AD, a supporting wall of the temple fell on its side, burying all the statues. They remained hidden under stone, rubble and earth for 1,630 years. The other walls sheltered the statues, so we were able to recover all the pieces, even works that had been broken."[26]

Beginning in 2006, Global Heritage Fund, in partnership with the Second University of Naples (SUN, Italy), the Libyan Department of Antiquities, and the Libyan Ministry of Culture, has been working to preserve the ancient site through a combination of holistic conservation practices and training of local skilled and unskilled labor. Apart from conducting ongoing emergency conservation on a theater inside the Sanctuary of Apollo through the process of anastylosis, the GHF-led team is in the process of developing a comprehensive master site management plan.[27]

In 2007 Muammar Gaddafi's son planned safeguarding Libya's archaeological sites and to prevent overdevelopment of Mediterranean coastlines.[28]

In May 2011, a number of objects excavated from Cyrene in 1917 and held in the vault of the National Commercial Bank in Benghazi were stolen. Looters tunnelled into the vault and broke into two safes that held the artefacts which were part of the so-called 'Benghazi Treasure'. The whereabouts of these objects are currently unknown.[29]

In 2017 UNESCO added Cyrene to its List of World Heritage in Danger.[30]

Notable residents

- Aristippus (c. 435 – c. 356 BC), philosopher and founder of the Cyrenaic School.

- Callimachus (310/305 – 240 BC), poet, critic, and scholar at the Library of Alexandria

- Eratosthenes (276 – 194 BC), mathematician, geographer, astronomer; librarian at the Library of Alexandria. First to calculate the circumference of the Earth.

- Eugammon (fl. 6th century BC), epic poet

- Lacydes (3rd century BC), philosopher

- Theodorus (c. 5th century BC), mathematician

Gallery

The Temple of Zeus

The Temple of Zeus The Tomb of Battus

The Tomb of Battus

The Temple of Zeus

The Temple of Zeus The Temple of Apollo

The Temple of Apollo

The Temple of Apollo

The Temple of Apollo Agora Victory Monument

Agora Victory Monument

See also

- Cyrenaica

- Cyrenaics

- List of Kings of Cyrene

- Extramural Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone at Cyrene, Libya

References

- "Platæa". Get A Map. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 23 Nov 2017.

- "Internet History Sourcebooks". sourcebooks.fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-12-03. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- Osborne, Robin (2009). Greece in the Making: 1200–479 BC. London: Routledge. p. 8.

- Thucydides (1998). Strassler, Robt. B. (ed.). The Peloponnesian War (The Landmark Thucydides ed.). New York: Touchstone. sec.7.50.

- Cassius Dio, lxviii. 32

- Plutarch. De Mulierum Virtutibus (Loeb Classical Library, Plutarch III) 1931. Retrieved February 2008.

- "Venus of Cyrene – Italy and Libya — Centre du droit de l'art". plone.unige.ch. Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- British Museum Collection

- "British Museum Highlights". Archived from the original on 2015-10-18. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- "British Museum Highlights". Archived from the original on 2015-10-18. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- Acts 2:10

- Martyrologium Romanum (Typographia Vaticana 2001 ISBN 978-88-209-7210-3)

- Michel Le Quien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus Archived 2017-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, (Paris 1740), Vol. II, coll. 621–624

- Raymond Janin, v. Cyrène in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques, vol. XIII, Paris 1956, coll. 1162–1164

- Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae Archived 2015-06-26 at the Wayback Machine, (Leipzig, 1931), p. 462.

- Michel Le Quien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus Archived 2018-04-03 at the Wayback Machine, (Parigi, 1740), volII, coll. 621–624.

- Anton Joseph Binterim, Suffraganei Colonienses extraordinarii, sive de sacrae Coloniensis ecclesiae proepiscopis Archived 2018-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, (Magonza, 1843).

- Raymond Janin, v. Cyrène in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques, vol. XIII, (Paris, 1956), coll. 1162–1164.

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 870

- Entry Archived 2017-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, at www.gcatholic.org

- titular See Cyrenaea Archived 2017-06-25 at the Wayback Machine at www.catholic-hierarchy.org

- Parejko, Ken (2003). "Pliny the Elder's Silphium: First Recorded Species Extinction". Conservation Biology. 17 (3): 925–927. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.02067.x. JSTOR 3095254.

- G. Mokhtar (1981). "Ancient Civilizations of Africa".

- https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/classics/intranets/students/modules/greekreligion/database/template-copyl/#:~:text=Archaeological%20Development&text=The%20Temple%20of%20Zeus%20was,time%20the%20site%20was%20abandoned.

- "21 World Heritage Sites you have probably never heard of". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2015-12-03. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- "Interview with archaeologist Mario Luni". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2009-05-22.

- Global Heritage Fund (GHF) Where We Work Archived 2009-04-09 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- "Reformed Libya eyes eco-tourist boom". BBC. 2007. Archived from the original on 2017-10-21. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- "Benghazi Treasure". Trafficking Culture Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2014-05-15. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- "Archaeological Site of Cyrene (Libya)". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cyrene. |

- Cyrene project summary at Global Heritage Fund

- Explore Cyrene with Google Earth on Global Heritage Network

- Cyrene and the Cyrenaica by Jona Lendering

- University of Pennsylvania Museum excavations at Cyrene