Nicomedes (mathematician)

Nicomedes (/ˌnɪkəˈmiːdiːz/; Greek: Νικομήδης; c. 280 – c. 210 BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician.

Life and work

Almost nothing is known about Nicomedes' life apart from references in his works. Studies have stated that Nicomedes was born in about 280 BC and died in about 210 BC. It is known that he lived around the time of Eratosthenes or after, because he criticized Eratosthenes' method of doubling the cube. It is also known that Apollonius of Perga called a curve of his creation a "sister of the conchoid", suggesting that he was naming it after Nicomedes' already famous curve. Consequently, it is believed that Nicomedes lived after Eratosthenes and before Apollonius of Perga.

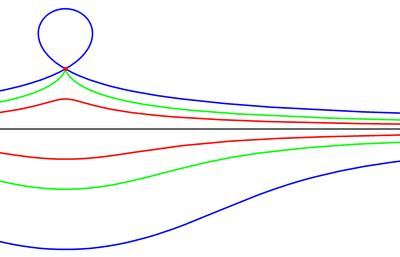

Like many geometers of the time, Nicomedes was engaged in trying to solve the problems of doubling the cube and trisecting the angle, both problems we now understand to be impossible using the tools of classical geometry. In the course of his investigations, Nicomedes created the conchoid[1] of Nicomedes; a discovery that is contained in his famous work entitled On conchoid lines. Nicomedes discovered three distinct types of conchoids, now unknown. Pappus wrote: "Nicomedes trisected any rectilinear angle by means of the conchoidal curves, the construction, order and properties of which he handed down, being himself the discoverer of their peculiar character".[2]

Nicomedes also used the Hippias' quadratrix to square the circle, since according to Pappus, "For the squaring of the circle there was used by Dinostratus, Nicomedes, and certain other later persons a certain curve which took its name from this property, for it is called by them square-forming".[2] Eutocius mentions that Nicomedes "prided himself inordinately on his discovery of this curve, contrasting it with Eratosthenes's mechanism for finding any number of mean proportionals, to which he objected formally and at length on the ground that it was impracticable and entirely outside the spirit of geometry".[2]

Citations and footnotes

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 826–827.

- Heath (1921)

References

- T. L. Heath, A History of Greek Mathematics (2 Vols.) (Oxford, 1921).

- G. J. Toomer, Biography in Dictionary of Scientific Biography (New York 1970–1990).