Parliament of Malaysia

The Parliament of Malaysia (Malay: Parlimen Malaysia) is the national legislature of Malaysia, based on the Westminster system. The bicameral parliament consists of the Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) and the Dewan Negara (Senate). The Yang di-Pertuan Agong (King) as the Head of State is the third component of Parliament.

Parliament of Malaysia Parlimen Malaysia | |

|---|---|

| 14th Parliament | |

Insignia of Parliament of Malaysia | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | Dewan Negara Dewan Rakyat |

| History | |

| Founded | 11 September 1959 |

| Preceded by | Federal Legislative Council |

| Leadership | |

Al-Sultan Abdullah since 31 January 2019 | |

Vacant since 22 June 2020 | |

| Structure | |

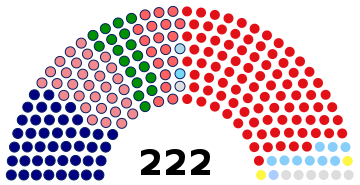

| Seats | 292 70 Senators 222 Members of Parliament |

| |

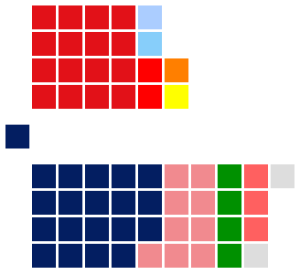

Dewan Negara political groups | As of 6 July 2020 Government (43)

Independent (1)

Opposition (21) Independent (1)

Vacant (4) |

| |

Dewan Rakyat political groups | As of 31 July 2020 Government (112)

Opposition (109) [1] PSB (2)

|

| Dewan Negara committees | 4

|

| Dewan Rakyat committees | 5

|

| Elections | |

| Indirect election and appointments | |

| First-past-the-post | |

Dewan Rakyat last election | 9 May 2018 |

Dewan Rakyat next election | 16 September 2023 or earlier |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Malaysian Houses of Parliament, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Parliament assembles in the Malaysian Houses of Parliament, located in the national capital city of Kuala Lumpur.

The term "Member of Parliament (MP)" usually refers to a member of the Dewan Rakyat, the lower house of the Parliament.

The term "Senator" usually refers to a member of the Dewan Negara, the upper house of the Parliament.

History

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Malaysia |

|

|

|

Colonial and the Federation of Malaya

Historically, none of the states forming the Federation of Malaysia had parliaments before independence, save for Sarawak which had its own Council Negeri which enabled local participation and representation in administrative work since 1863. Although the British colonial government had permitted the forming of legislative councils for Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak, these were not the supreme makers of law, and remained subordinate to the British High Commissioner or the Rajah, in case of Sarawak.

The Reid Commission, which drafted the Constitution of Malaya — Malaya gained independence in 1957, ahead of the other states that would later form Malaysia – modelled the Malayan system of government after the British system: a bicameral parliament, with one house being directly elected, and the other having limited powers with some members being appointed by the King, as is the case with the British House of Commons and House of Lords. In line with the federal nature of the new country, the upper house would also have members elected by state legislative assemblies in addition to members appointed by the King.

The Constitution provided for the pre-independence Federal Legislative Council to continue to sit as the legislative body of the new country until 1959, when the first post-independence general election were held and the first Parliament of Malaya were elected.

Parliament first sat at the former headquarters building of the Federated Malay States Volunteer Force on a hill near Jalan Tun Ismail (Maxwell Road). The Dewan Negara met in a hall on the ground floor while the Dewan Rakyat met in the hall on the first floor.[2] With the completion of Parliament House in 1962, comprising a three-storey main building for the two houses of Parliament to meet, and an 18-storey tower for the offices of Ministers and members of Parliament, both houses moved there.

Malaysia

In 1963, when Malaya, Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore merged to form Malaysia, the Malayan Parliament was adopted for use as the Parliament of Malaysia. Both Dewan Rakyat and Dewan Negara were expanded to include representatives from the new states. When Singapore seceded from Malaysia in 1965, it ceased to be represented in the Parliament of Malaysia.

Significant change regarding the composition of Dewan Negara occurred during this period. Under the 1957 Constitution of Malaya, senators elected by the state assemblies were in the majority, totalling 22 members with 2 for each state, while there were only 16 appointed members. The 1963 Constitution of Malaysia retains the provision that each state sends two senators, but subsequent amendments gradually increased the number of appointed members to 40 (plus another 4 appointed for representing the federal territories), leaving state-elected members in the minority and effectively diminishing the states' representation in Dewan Negara.[3]

Parliament has been suspended only once in the history of Malaysia, in the aftermath of the 13 May race riots in 1969. From 1969 to 1971 – when Parliament reconvened – the nation was run by the National Operations Council (NOC).

Debates in Parliament are broadcast on radio and television occasionally, such as during the tabling of a budget. Proposals from the opposition to broadcast all debates live have been repeatedly rejected by the government; in one instance, a Minister said that the government was concerned over the poor conduct of the opposition as being inappropriate for broadcasting. The prohibitive cost (RM100,000 per sitting) was also cited as a reason.[4]

In 2006, Information Minister Zainuddin Maidin cited the controversy over speeches made at the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) — the leading party in the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition – annual general assembly as a reason to avoid telecasting Parliamentary debates. Zainuddin said that "our society has not attained a mental maturity where it is insensitive to racial issues", citing the controversy over a delegate who said Malays would fight "to the last drop of blood" to defend the special provisions granted to them as bumiputra under the Constitution.[5]

Composition and powers

As the ultimate legislative body in Malaysia, the Parliament is responsible for passing, amending and repealing acts of law. It is subordinate to the Head of State, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, under Article 39 of the Constitution.[6]

The Dewan Rakyat consists of 222 members of Parliament (MPs) elected from single-member constituencies drawn based on population in a general election using the first-past-the-post system. A general election is held every five years or when Parliament is dissolved by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong on the advice of the Prime Minister. Suffrage is given to registered voters 21 years and above, however voting is not compulsory. The age requirement to stand for election is 21 years and above. When a member of Parliament dies, resigns or become disqualified to hold a seat, a by-election is held in his constituency unless the tenure for the current Parliament is less than two years, where the seat is simply left vacant until the next general election.

The Dewan Negara consists of 70 members (Senators); 26 are elected by the 13 state assemblies (2 senators per state), 4 are appointed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong to represent the 3 federal territories (2 for Kuala Lumpur, 1 each for Putrajaya and Labuan). The rest 40 members are appointed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong on the advice of the Prime Minister. Senators must be 30 years or above, and are appointed to a three-year term for a maximum of two terms. The dissolution of the Parliament does not affect the Dewan Negara.

Members of Parliament are permitted to speak on any subject without fear of censure outside Parliament; the only body that can censure an MP is the House Committee of Privileges. Parliamentary immunity takes effect from the moment a member of Parliament is sworn in, and only applies when that member has the floor; it does not apply to statements made outside the House. An exception to this rule are portions of the constitution related to the social contract, such as the Articles governing citizenship, Bumiputera (Malays and indigenous people) priorities, the Malay language, etc. — all public questioning of these provisions is illegal under the 1971 amendments to the Sedition Act, which Parliament passed in the wake of the 1969 13 May race riots.[7] Members of Parliament are also forbidden from criticising the Yang di-Pertuan Agong and judges.[8] Parliamentary immunity and other such privileges are set out by Article 63 of the Constitution; as such, the specific exceptions to such immunity had to be included in the Constitution by amendment after the 13 May incident.

The executive government, comprising the Prime Minister and his Cabinet, is drawn from the members of Parliament and is responsible to the Parliament. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong appoints the Prime Minister, who is the Head of Government but constitutionally subordinant to His Majesty, from the Dewan Rakyat. In practice, the Prime Minister shall be the one who commands the confidence of the majority of the Dewan Rakyat. The Prime Minister then submits a list containing the names of members of his Cabinet, who will then be appointed as Ministers by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong. Members of the Cabinet must also be members of Parliament, usually from the Dewan Rakyat. The Cabinet formulates government policy and drafts bills, meeting in private. The members must accept "collective responsibility" for the decisions the Cabinet makes, even if some members disagree with it; if they do not wish to be held responsible for Cabinet decisions, they must resign. Although the Constitution makes no provision for it, there is also a Deputy Prime Minister, who is the de facto successor of the Prime Minister should he die, resign or be otherwise incapacitated.[6]

If the Prime Minister loses the confidence of the Dewan Rakyat, whether by losing a no-confidence vote or by failing to pass a budget, he must either submit his resignation to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, or ask His Majesty to dissolve the Parliament. If His Majesty refuses to dissolve the Parliament (one of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong discretionary powers), the Cabinet must resign and the Yang di-Pertuan Agong will appoint a new Prime Minister.

Although the judiciary is constitutionally an independent branch of the government, after the 1988 constitutional crisis, the judiciary was made subject to Parliament; judicial powers are held by Parliament, and vested by it in the courts, instead of being directly held by the judiciary as before. The Attorney-General was also conferred the power to instruct the courts on what cases to hear, where they would be heard, and whether to discontinue a particular case.[9]

After the general elections in 2008, Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, leader of the People's Justice Party and wife of former deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim became the leader of the opposition. She is the first female in Malaysian history to have held this position.[10] Wan Azizah is described as the "brains" behind the coalition of her own party, the 'leftist' Democratic Action Party (DAP) and the religion based Pan Malaysian Islamic Party.[11]

Procedure

Parliament meets from Monday to Thursday when it is in session, as Friday is part of the weekend in the states of Johor, Kelantan, Kedah, and Terengganu.[12]

A proposed act of law begins its life when a particular government minister or ministry prepares a first draft with the assistance of the Attorney-General's Department. The draft, known as a bill, is then discussed by the Cabinet. If it is agreed to be submitted to Parliament, the bill is distributed to all MPs. It then goes through three readings before the Dewan Rakyat. The first reading is where the minister or his deputy submits it to Parliament. At the second reading, the bill is discussed and debated by MPs. Until the mid-1970s, both English and Malay (the national language) were used for debates, but henceforth, only Malay was permitted, unless permission was obtained from the Speaker of the House. At the third reading, the minister or his deputy formally submit it to a vote for approval. A 2/3 majority is usually required to pass the bill, but in certain cases, a simple majority suffices. Should the bill pass, it is sent to the Dewan Negara, where the three readings are carried out again. The Dewan Negara may choose not to pass the bill, but this only delays its passage by a month, or in some cases, a year; once this period expires, the bill is considered to have been passed by the house.[12][13]

If the bill passes, it is presented to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, who has 30 days to consider the bill. Should he disagree with it, he returns it to Parliament with a list of suggested amendments. Parliament must then reconsider the bill and its proposed amendments and return it to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong within 30 days if they pass it again. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong then has another 30 days to give the royal assent; otherwise, it passes into law. The law does not take effect until it is published in the Government Gazette.[14]

The government attempts to maintain top secrecy regarding bills debated; MPs generally receive copies of bills only a few days before they are debated, and newspapers are rarely provided with copies of the bills before they are debated. In some cases, such as a 1968 amendment to the Constitution, an MP may be presented with a bill to be debated on the same day it is tabled, and all three readings may be carried out that day itself.[15] In rare circumstances, the government may release a White paper containing particular proposals that will eventually be incorporated into a bill; this has been done for legislation such as the Universities and University Colleges Act.[16]

Although the process above assumes only the government can propose bills, there also exists a process for Private Member's Bills. However, as in most other legislatures following the Westminster System, few members of Parliament actually introduce bills.[17] To present a Private Member's Bill, the member in question must seek the leave of the House in question to debate the bill before it is moved. Originally, it was allowed to debate the bill in the process of seeking leave, but this process was discontinued by an amendment to the Standing Orders of Parliament.[18] It is also possible for members of the Dewan Negara (Senate) to initiate bills; however, only cabinet ministers are permitted to move finance-related bills, which must be tabled in the Dewan Rakyat.[19]

It is often alleged that legislation proposed by the opposition parties, which must naturally be in the form of a Private Member's Bill, is not seriously considered by Parliament. Some have gone as far as to claim that the rights of members of Parliament to debate proposed bills have been severely curtailed by incidents such as an amendment of the Standing Orders that permitted the Speaker of the Dewan Rakyat to amend written copies of MPs' speeches before they were made. Nevertheless, some of these critics also suggest that "Government officials often face sharp questioning in Parliament, although this is not always reported in detail in the press."[9]

Most motions are typically approved or rejected by a voice vote; divisions are generally rare. In 2008, the 12th Parliament saw the first division on the question of a supply bill.[20]

In June 2008, two MPs announced they would be supporting a motion of no confidence against the Prime Minister, another first in the history of Parliament. The procedure surrounding a vote of no confidence is not entirely clear; as of 18 June 2008 it appeared there was no provision in the Standing Orders for whether a simple majority or a 2/3 supermajority would be necessary to pass a vote of no confidence[21]

Relationship with the government

In theory, based on the Constitution of Malaysia, the government is accountable to Parliament. However, there has been substantial controversy over the independence of the Malaysian Parliament, with many viewing it simply as a rubber stamp, approving the executive branch's decisions. Constitutional scholar Shad Saleem Faruqi has calculated that 80% of all bills the government introduced from 1991 to 1995 were passed without a single amendment. According to him, another 15% were withdrawn due to pressure from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or other countries, while only 5% were amended or otherwise altered by Parliament. Shad concludes that "the legislative process is basically an executive process, not a parliamentary process."[22]

Checks and balances

Theoretically, the executive branch of the government held in check by the legislative and judiciary branches. Parliament largely exerts control on the government through question time, where MPs question members of the cabinet on government policy, and through Select committees that are formed to look into a particular issue.

Formally, Parliament exercises control over legislation and financial affairs. However, the legislature has been condemned as having a "tendency to confer wide powers on ministers to enact delegated legislation", and a substantial portion of the government's revenue is not under Parliament's purview; government-linked companies, such as Petronas, are generally not accountable to Parliament.[23] In his 1970 book The Malay Dilemma, former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad stated: "In the main, Parliamentary sittings were regarded as a pleasant formality which afforded members opportunities to be heard and quoted, but which would have absolutely no effect on the course of the Government. ... The sittings were a concession to a superfluous democratic practice. Its main value lay in the opportunity to flaunt Government strength."[24] Critics have regarded Parliament as a "safe outlet for the grievances of backbenchers or opposition members," and meant largely to "endorse government or ruling party proposals" rather than act as a check on them.[25]

Party loyalty is strictly enforced by the Barisan Nasional coalition government, which has controlled Parliament since independence. Those who have voted against the frontbench position, such as Shahrir Abdul Samad, have generally been severely reprimanded. Although there is no precedent of an MP being removed from the house for crossing the floor, two Penang State Legislative Assemblymen who abstained from voting on an opposition-tabled motion in the State Legislative Assembly were suspended, and a stern warning was issued by then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad stating that representatives from BN would likely be dismissed if they crossed the floor.[26] This was later affirmed by Mahathir's successor, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, who issued an official directive prohibiting BN MPs from voting for opposition-tabled motions in Parliament.[27]

At one time, there was an attempt led by government backbenchers to gain Abdullah's support for a policy change which would permit some discretion in voting, but Abdullah insisted that MPs have "no leeway or freedom to do as they like". A similar policy is in place in the non-partisan Dewan Negara — when in 2005, several Senators refused to support the Islamic Family Law (Federal Territories) (Amendment) Bill 2005, Minister in the Prime Minister's Department Nazri Aziz said that although the government would take note of the complaints, "the cabinet did not allow senators to exercise conscience voting on this issue".[28]

There have been only six Select Committees formed since 1970, when Parliament reconvened after the May 13 Incident. Of these, three were formed between 2002 and 2005. Although question time exists for Parliament to check the power of the executive, it has been argued that the question time allotted for MPs to question the government on its policies is insufficient or ineffective. Shad has calculated that as each question time session lasts only an hour, at the most, twelve questions can be asked. Opposition Leader Lim Kit Siang of the Democratic Action Party (DAP) calculated that over the space of three days (from 10 to 13 October 2005), only 32 questions were answered orally. Of these 32 questions, only nine or 28% percent were answered by the Ministers concerned. The rest were answered either by Deputy Ministers (41%) or Parliamentary Secretaries (31%).[22][29] After the 2008 general election, Abdullah reshuffled his Cabinet, eliminating Parliamentary Secretaries, which The Sun greeted as a move "forcing ministers and deputy ministers to answer questions in Parliament".[30]

Time is allocated for discussion of the annual budget after it is tabled by the Minister of Finance; however, most MPs spend much of the time questioning the government on other issues. Shad contends that although about 20 days are given for discussion of the budget, "the budget debate is used to hit the government on the head about everything else other than the budget. From potholes to education policy to illegal immigrants."[22] If Parliament votes to reject the budget, it is taken as a vote of no-confidence, forcing the government out of office. The government will then either have to reform itself with a new cabinet and possibly new Prime Minister, or call for a general election. As a result, Shad states that "MPs may criticize, they may have their say but the government will have its way" when it comes to the budget.[22]

With the judiciary, it is possible for the courts to declare a particular act of Parliament unconstitutional. However, this has never occurred. Parliament is not involved in the process of judicial appointments.[31]

Department of Parliament controversy

In early October 2005, the Minister in the Prime Minister's Department in charge of parliamentary affairs, Nazri Aziz, announced the formation of a Department of Parliament to oversee its day-to-day running. The leader of the Opposition, Lim Kit Siang, immediately announced a "Save Parliament" campaign to "ensure that Parliament does not become a victim in the second most serious assault on the doctrine of separation of powers in the 48-year history of the nation".[32]

Nazri soon backed down, saying he had meant an office (although he stated jabatan, which means department; pejabat is the Malay word for office) and not Department (Jabatan) of Parliament. The New Straits Times, a newspaper owned by the United Malays National Organisation (a key member of the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition) wrote in an editorial that "ministerial authority was established over Parliament the building" and not Parliament the institution and that "[i]f the new 'department' and its management and staff do their jobs well, the rakyat (people) would have even more of a right to expect their MPs to do theirs by turning up for Dewan sessions, preserving that quaint tradition of the quorum, on behalf of their constituencies."[33]

Lim was dissatisfied with such a response and went ahead with a "Save Parliament" roundtable attended by several MPs (including Nazri) and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Although Lim thanked Nazri (the only Barisan Nasional MP in attendance), he stated that the proposed department remained a threat to Parliament's independence, and had to be "seen in the context of the relentless erosion and diminution of parliamentary powers and functions by the Executive". In a statement, the roundtable found that "Nazri's explanations were not convincing" and urged "Nazri to halt all implementation of the Cabinet decision to establish a Department or Office of Parliament until MPs and the civil society could approve and support the proposal".[34]

On 13 October in the Dewan Rakyat, Ahmad Shabery Cheek (BN MP for Kemaman) tabled a motion to reinstate the Parliamentary Services Act 1963 (which would provide for a parliamentary service independent of the Public Service Department currently handling parliamentary affairs) that had been repealed (upon the unilateral suggestion of then-Speaker Zahir Ismail) in 1992. Ahmad Shabery demanded to know if the government would make the status of parliament as an independent institution clear, and stated that "Aside from nice flooring, chairs and walls, we don’t even have a library that can make us proud, no in-house outlet selling copies of different Acts that are passed in Parliament itself and no proper information centre."[35]

Nazri responded that the motion would have to be referred to the House Committee for review. Shahrir Abdul Samad, chairman of the Barisan Nasional Backbenchers Club, then insisted that the Act be immediately restored without being referred to the Committee, and called on all MPs who supported the motion to stand. Several immediately stood, with some Opposition MPs shouting "bangun, bangun" (stand up, stand up). Following Shahrir's lead, a majority of the BN MPs also stood, including some frontbenchers. However, several ministers, including Foreign Minister Syed Hamid Albar (who had supported repealing the Act in 1992) remained seated. Nazri then stated that the matter would remain with the Committee, as he did not want it dealt with in a slipshod manner.[35]

The following day, Lim called on Kamaruddin Mohd Baria, who would have taken the post of Parliament Head of Administration, not to report for duty in his new post. Meanwhile, the Dewan Negara House Committee held a specially-convened meeting, which called on the government to revive the Act and to call off all moves to change the administrative structure of Parliament. The President of the Dewan Negara, Abdul Hamid Pawanteh, also stated that he had not been informed "at all" by the government regarding the new department or office of Parliament. Later the same day, Minister in the Prime Minister's Department Mohd Radzi Sheikh Ahmad stated that the government had agreed to revive the Act.[36]

However, on 17 October, Nazri refused to budge on the issue of the new post of "Parliament Head of Administration" (which would make the current Parliamentary Secretary, who is accountable to Parliament and not the executive, redundant). He also stated that the Parliamentary Services Act would have to go through the Dewan Rakyat House Committee and endorsed by the Dewan Rakyat before being sent to the cabinet for approval. In his blog, Lim slammed Nazri for overlooking "the fact that when the Parliamentary Privilege Act was repealed in 1992, it was not at the recommendation of the Dewan Rakyat House Committee but merely at the unilateral request of the Speaker."[37]

Dewan Negara

The Dewan Negara (Malay for Senate, literally National Council) is the upper house of the Parliament of Malaysia, consisting of 70 senators of whom 26 are elected by the state legislative assemblies, with two senators for each state, while the other 44 are appointed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (King), including four of whom are appointed to represent the federal territories.

The Dewan Negara usually reviews legislation that has been passed by the lower house, the Dewan Rakyat. All bills must usually be passed by both the Dewan Rakyat and the Dewan Negara (the Senate), before they are sent to the King for royal assent. However, if the Dewan Negara rejects a bill, it can only delay the bill's passage by a maximum of a year before it is sent to the King. Like the Dewan Rakyat, the Dewan Negara meets at the Malaysian Houses of Parliament in Kuala Lumpur.

Dewan Rakyat

The Dewan Rakyat (Malay for House of Representatives, literally People's Hall) is the lower house of the Parliament of Malaysia, consisting of members elected during elections from federal constituencies drawn by the Election Commission.

The Dewan Rakyat usually proposes legislation through a draft known as a 'bill'. All bills must usually be passed by both the Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) and the Dewan Negara, before they are sent to the King for royal assent. However, if the Dewan Negara rejects a bill, it can only delay the bill's passage by a maximum of a year before it is sent to the King. Like the Dewan Negara, the Dewan Rakyat meets at the Malaysian Houses of Parliament in Kuala Lumpur.

See also

Notes

- Two independent senators hold ministerial portfolios.

References

- https://www.sinarharian.com.my/article/92931/BERITA/Politik/Bersatu-pecat-Ahli-Parlimen-Sri-Gading

- Interview on 28 March 2011 with retired JKR engineer, Yoon Shee Leng, who built Parliament House.

- Funston, John (2001). "Malaysia: Developmental State Challenged". In John Funston (Ed.), Government and Politics in Southeast Asia, pp. 180, 183. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- "MALAYSIA: Why Parliament sessions can't go live on TV". (6 May 2004). Straits Times.

- Malaysia "not mature" enough for parliament broadcasts: minister. Malaysia Today.

- "Branches of Government in Malaysia" Archived 7 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 February 2006.

- Means, Gordon P. (1991). Malaysian Politics: The Second Generation, pp. 14, 15. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-588988-6.

- Myytenaere, Robert (1998). "The Immunities of Members of Parliament" Archived 25 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- "Malaysia". Retrieved 22 January 2006.

- Malaysia Has A Female Opposition Leader For The First Time In History Archived 23 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. AHN, 28 April 2008

- Malaysia's new lawmakers take oath of office to join Parliament after historic polls. International Herald tribune. 28 April 2008

- Lim, Kit Siang (2004). "Master English campaign – one day a week in Parliament for free use of English". Retrieved 15 February 2006.

- Shuid, Mahdi & Yunus, Mohd. Fauzi (2001). Malaysian Studies, pp. 33, 34. Longman. ISBN 983-74-2024-3.

- Shuid & Yunus, p. 34.

- Tan, Chee Koon & Vasil, Raj (ed., 1984). Without Fear or Favour, p. 7. Eastern Universities Press. ISBN 967-908-051-X.

- Tan & Vasil, p. 11.

- Ram, B. Suresh (16 December 2005). "Pro-people, passionate politician" Archived 27 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine. The Sun.

- Lim, Kit Siang (1997). "Consensus Against Corruption". Retrieved 11 February 2006.

- Henderson, John William, Vreeland, Nena, Dana, Glenn B., Hurwitz, Geoffrey B., Just, Peter, Moeller, Philip W. & Shinn, R.S. (1977). Area Handbook for Malaysia, p. 219. American University, Washington D.C., Foreign Area Studies. LCCN 771294.

- "Bill approved by block voting for first time". The Malaysian Insider. 29 May 2008. Archived from the original on 12 February 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- Beh, Lih Yi (18 June 2008). "No-confidence vote: No way, Sapp!". Malaysiakini. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- Ahmad, Zainon & Phang, Llew-Ann (1 October 2005). The all-powerful executive. The Sun.

- Funston, p. 180.

- Mohammad, Mahathir bin. The Malay Dilemma, p. 11.

- "Conclusion". In John Funston (Ed.) Government and Politics in Southeast Asia, p. 415.

- Yap, Mun Ching (21 December 2006). A sorry state of Parliament Archived 22 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. The Sun.

- Megan, M.K. & Andres, Leslie (9 May 2006). "Abdullah: Vote along party lines", p. 4. New Straits Times.

- Ahmad, Zainon (29 December 2006). World-class Parliament still a dream Archived 22 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. The Sun.

- Lim, Kit Siang (2005). "The day Dr. Mahathir was 'taken for a ride' by Rafidah". Retrieved 15 October 2005.

- Yusop, Husna; Llew-Ann Phang (18 March 2008). "Leaner govt, Cabinet surprises". The Sun. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- Funston, p. 183.

- Lim, Kit Siang (2005). "'Save Parliament' campaign". Retrieved 12 October 2005.

- "Order in the House". (12 October 2005). New Straits Times, p. 18.

- Lim, Kit Siang (2005). "Minister for 'First-World' Parliament – not Minister for Parliament toilets and canteen". Retrieved 12 October 2005.

- "Resounding aye to power separation". (14 October 2005). New Straits Times, p. 8.

- Lim, Kit Siang (2005). "Skies brighten for Parliament after a week of dark clouds". Retrieved 14 October 2005.

- Lim, Kit Siang (2005). "Sorry I was wrong, there is still no light at the end of the tunnel". Retrieved 17 October 2005.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parliament of Malaysia. |

- Official website (in Malay)