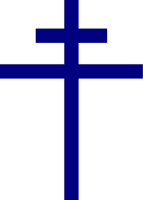

Patriarchal cross

The Patriarchal cross is a variant of the Christian cross, the religious symbol of Christianity, and also known as the Cross of Lorraine. Similar to the familiar Latin cross, the patriarchal cross possesses a smaller crossbar placed above the main one so that both crossbars are near the top. Sometimes the patriarchal cross has a short, slanted crosspiece near its foot (Russian Orthodox cross). This slanted, lower crosspiece often appears in Byzantine Greek and Eastern European iconography, as well as in other Eastern Orthodox churches.

The Patriarchal cross first regularly appeared on the coinage of the Byzantine Empire starting with the second reign of the emperor Justinian II, whose second reign was from 705-711. At the beginning of the second reign, the emperor was depicted on the solidus holding a globus cruciger with a Patriarchal cross at the top of the globe.[1] Until that time, the standard practice was to show the globus cruciger with an ordinary cross. The emperor Theodosius III, who ruled from 715 to 717, made the Patriarchal cross a standard feature of the gold, silver and bronze coinage minted in Constantinople.[2] After his short reign ended, the practice was discontinued under his successor, Leo III, and was not revived again until the middle of the eighth century by the usurper Artavasdus.

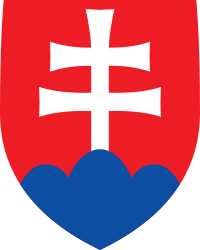

The Byzantine Christianization came to the Morava Empire in the year 863, provided at the request of Rastislav sent Byzantine Emperor Michael III.[3] The symbol, often referred to as the patriarchal cross, appeared in the Byzantine Empire in large numbers in the 10th century. For a long time, it was thought to have been given to Saint Stephen by the pope as the symbol of the apostolic Kingdom of Hungary.

The two-barred cross has been one of the main elements in the coat of arms of Hungary since 1190. It appeared during the reign of King Béla III, who was raised in the Byzantine court. Béla was the son of Russian princess Eufrosina Mstislavovna. The cross appears floating in the coat of arms and on the coins from this era. In medieval Kingdom of Hungary was extended Byzantine Cyril-Methodian and western Latin church was expanded later.[4]

The two-barred cross in the Hungarian coat of arms comes from the same source of Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire in the 12th century. Unlike the ordinary Christian cross, the symbolism and meaning of the double cross is not well understood.

In most renditions of the Cross of Lorraine, the horizontal bars are "graded" with the upper bar being the shorter, though variations with the bars of equal length are also seen.

Imagery

The top beam represents the plaque bearing the inscription "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews" (often abbreviated in the Latinate "INRI", and in the Greek as "INBI"). A popular view is that the slanted bottom beam is a foot rest, however there is no evidence of foot rests ever being used during crucifixion, and it has a deeper meaning. The bottom beam may represent a balance of justice. Some sources suggest that, as one of the thieves being crucified with Jesus repented of his sin and believed in Jesus as the Messiah and was thus with Christ in Paradise, the other thief rejected and mocked Jesus and therefore descended into Hades.

Many symbolic interpretations of the double cross have been put forth. One of them says that the first horizontal line symbolized the secular power and the other horizontal line the ecclesiastic power of Byzantine emperors. Also, that the first cross bar represents the death and the second cross the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

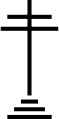

Other variations

The Russian cross can be considered a modified version of the Patriarchal cross, having two smaller crossbeams, one at the top and one near the bottom, in addition to the longer crossbeam. One suggestion is the lower crossbeam represents the footrest (suppedaneum) to which the feet of Jesus were nailed. In some earlier representations (and still currently in the Greek Church) the crossbar near the bottom is straight, or slanted upwards. In later Slavic and other traditions, it came to be depicted as slanted, with the side to the viewer's left usually being higher. During 1577–1625 the Russian use of the cross was between the heads of the double-headed eagle in the coat of arms of Russia.

One tradition says that this comes from the idea that as Jesus Christ took his last breath, the bar to which his feet were nailed broke, thus slanting to the side. Another tradition holds that the slanted bar represents the repentant thief and the unrepentant thief that were crucified with Christ, the one to Jesus' right hand repenting and rising to be with God in Paradise, and one on his left falling to Hades and separation from God. In this manner it also reminds the viewer of the Last Judgment.

Still another explanation of the slanted crossbar would suggest the Cross Saltire, as tradition holds that the Apostle St. Andrew introduced Christianity to lands north and west of the Black Sea: today's Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, Moldova, and Romania.

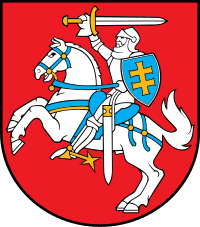

Another form of the cross was used by the Jagiellonian dynasty in Poland. This cross now features on the coat of arms of Lithuania, where it appears on the shield of the knight. It is also the badge of the Lithuanian Air Force and forms the country's highest award for bravery, the Order of the Cross of Vytis.

The Patriarchal Cross appears on the Pahonia, used at various times as the coat of arms of Belarus.

Roman Catholic metropolitan archbishop's coat of arms (version with pallium

Roman Catholic metropolitan archbishop's coat of arms (version with pallium Saint Stephen, the first King of Hungary (1000–1038).

Saint Stephen, the first King of Hungary (1000–1038)..svg.png) Coat of arms of Hungary under king Béla III

Coat of arms of Hungary under king Béla III

Archangel Gabriel holds the Holy Crown and the apostolic double cross as the symbols of Hungary, Hősök tere, Budapest, Hungary

Archangel Gabriel holds the Holy Crown and the apostolic double cross as the symbols of Hungary, Hősök tere, Budapest, Hungary The globus cruciger of Hungary (right) is unique in having a patriarchal cross instead of a simple cross

The globus cruciger of Hungary (right) is unique in having a patriarchal cross instead of a simple cross Coat of arms of King Jogaila of Lithuania

Coat of arms of King Jogaila of Lithuania The coat of arms of Lithuania, with the patriarchal cross on the knight's shield

The coat of arms of Lithuania, with the patriarchal cross on the knight's shield.svg.png)

Coat of arms of the city of Nitra, Slovakia

Coat of arms of the city of Nitra, Slovakia Coat of arms of the city of Skalica, Slovakia

Coat of arms of the city of Skalica, Slovakia Coat of arms of the city of Levoča, Slovakia

Coat of arms of the city of Levoča, Slovakia Coat of arms of the city of Žilina, Slovakia

Coat of arms of the city of Žilina, Slovakia Coat of arms of the city of Zvolen, Slovakia

Coat of arms of the city of Zvolen, Slovakia Coat of arms of Pest County, Hungary

Coat of arms of Pest County, Hungary_variant_2.svg.png) Flag of the Hlinka's Slovak People's Party 1938 to 1945

Flag of the Hlinka's Slovak People's Party 1938 to 1945 The badge of the Lithuanian Air Force

The badge of the Lithuanian Air Force Serbian Emperor Stefan Dušan holding the patriarchal cross.

Serbian Emperor Stefan Dušan holding the patriarchal cross. The Russian cross, with slanted cross-bar (suppedaneum)

The Russian cross, with slanted cross-bar (suppedaneum) A variation of the Russian cross, so called "Calvary cross"

A variation of the Russian cross, so called "Calvary cross" Archangels' cross

Archangels' cross Archangels' cross variant

Archangels' cross variant

Typefaces

Unicode defines the character ☦ (Russian cross) and ☨ (Cross of Lorraine) in the Miscellaneous Symbols range at code point U+2626 and U+2628 respectively.

References

- Breckenridge, James (1959). The Numismatic Iconography of Justinian II. The American Numismatic Society. p. 23.

- Sear, David (1987). Byzantine Coins and Their Values. Seaby. pp. 283–84. ISBN 0900652713.

- Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 22.

- František Vít̕azoslav Sasinek: Dejiny počiatkov terajšieho Uhorska, Bánská Bystrica, 1868 (Slovak language)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Patriarchal cross. |