Philoxenus of Mabbug

Philoxenus of Mabbug (Syriac: ܐܟܣܢܝܐ ܡܒܘܓܝܐ, Aksenāyâ Mabûḡāyâ) (died 523), also known as Xenaias and Philoxenus of Hierapolis, was one of the most notable Syriac prose writers and a vehement champion of Miaphysitism.

Early life

He was born, probably in the third quarter of the 5th century, at Tahal, a village in the district of Beth Garmaï east of the Tigris. He was thus by birth a subject of Persia, but all his active life of which we have any record was passed in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. His parents were from the Median city of Ecbatana.[1] The statements that he had been a slave and was never baptized appear to be malicious inventions of his theological opponents. He was educated at Edessa, perhaps in the famous "school of the Persians," which was afterwards (in 489) expelled from Edessa on account of its connection with Nestorianism.

Background

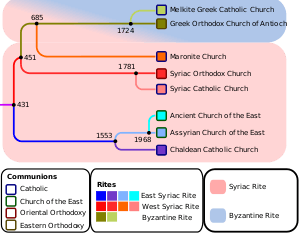

The years which followed the Council of Chalcedon (451) were a stormy period in the Syriac Church. Philoxenus soon attracted notice by his strenuous advocacy of Miaphysitism.

When Calandio, the Chalcedonian patriarch of Antioch, was expelled by the Miaphysite Peter the Fuller in 485, Philoxenus was ordained bishop of Mabbug.[2] It was probably during the earlier years of his episcopate that Philoxenus composed his thirteen homilies on the Christian life.

Syriac Bible

Later he devoted himself to the revision of the Syriac versions of the Bible, and with the help of his chorbishop Polycarp produced in 508 the so-called Philoxenian version, which was in some sense the received Bible of the Syriac Miaphysites during the 6th century. In the meantime he continued his ecclesiastical activity, working as a bitter opponent of Flavian II, who was patriarch of Antioch from 498 to 512 and accepted the decrees of the Council of Chalcedon.

With the support of Emperor Anastasius, the Miaphysites ousted Flavian in 512 and replaced him with their partisan Severus. Of Philoxenus's part in the struggle we possess not too trustworthy accounts by hostile writers, such as Theophanes the Confessor and Theodorus Lector. We know that in 498 he was staying at Edessa; in or about 507, according to Theophanes, he was summoned by the emperor to Constantinople; and he finally presided at a synod at Sidon which was the means of procuring the replacement of Flavian by Severus. But the triumph was short-lived. Justin I, who succeeded Anastasius in 518 and adhered to the Chalcedonian creed, exiled Severus and Philoxenus in 519. Philoxenus was banished to Philippopolis in Thrace, and afterwards to Gangra in Paphlagonia, where he was murdered in 523.[3]

Writings

Apart from his redoubtable powers as a controversialist, Philoxenus is remembered as a scholar, an elegant writer, and an exponent of practical Christianity. Of the chief monument of his scholarship – the Philoxenian version of the Bible – only the Gospels and certain portions of Isaiah are known to survive (see Wright, Syr. Lit. 14). It was an attempt to provide a more accurate rendering of the Septuagint than had hitherto existed in Syriac, and obtained recognition among Syriac Miaphysites until superseded by the still more literal renderings of the Old Testament by Paul of Tella and of the New Testament by Thomas of Harkel (both in 616/617), of which the latter at least was based on the work of Philoxenus.

There are also extant portions of commentaries on the Gospels from his pen. Of the excellence of his style and of his practical religious zeal we are able to judge from the thirteen homilies on the Christian life and character which have been edited and translated by E. A. Wallis Budge (London, 1894). In these he holds aloof for the most part from theological controversy, and treats in an admirable tone and spirit the themes of faith, simplicity, the fear of God, poverty, greed, abstinence and unchastity. His affinity with his earlier countryman Aphraates is manifest both in his choice of subjects and his manner of treatment. As his quotations from Scripture appear to be made from the Peshitta, he probably wrote the homilies before he embarked upon the Philoxenian version. Philoxenus wrote also many controversial works and some liturgical pieces. Many of his letters survive, and at least two have been edited. Several of his writings were translated into Arabic and Ethiopic.

Notes

- Wigram, William Ainger (1910) An introduction to the history of the Assyrian Church or the church of the Sassanid Persian Empire, 100-640 A.D., Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, UK.

- Barhebraeus, Chron. eccl. i. 183

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

References

Further reading

- Michelson, David A., "The Practical Christology of Philoxenos of Mabbug", Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Walters, James E., "The Philoxenian Gospels as Reconstructed from the Writings of Philoxenos of Mabbug", Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studes 13.2 (Summer 2010).