Alqosh

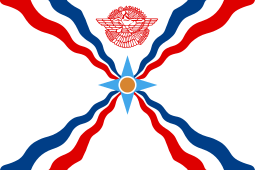

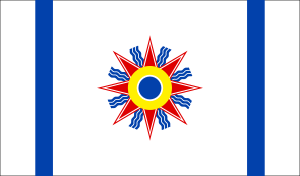

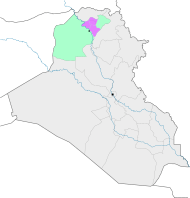

Alqosh (Syriac: ܐܲܠܩܘܿܫ,[2][3][4] Judeo-Aramaic: אלקוש, Arabic: ألقوش,[1] alternatively spelled Alkosh or Alqush) is an ethnic Assyrian[5][6] village in the Nineveh plains of northern Iraq. It is a sub-district of the Tel Kaif District and is 45 km north of the city of Mosul. It is the site of a military base of the Nineveh Plain Protection Units.[7][8][9] Colonel R. S. Stafford, who was the British Administrative Inspector for Mosul, referred to Alqosh as an "Assyrian center" where another massacre (in reference to the Simele massacre) was planned.[10]

Alqosh ܐܲܠܩܘܿܫ ألقوش[1] | |

|---|---|

Village | |

General view of Alqosh | |

Alqosh | |

| Coordinates: 36°43′55.6″N 43°5′42.6″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Ninawa |

| District | Tel Kaif (officially) |

| Founded | 1500 BC |

| Time zone | GMT +3 |

| • Summer (DST) | GMT +4 |

Christianity

The importance of Alqosh for the Church of the East arose from its proximity to the Rabban Hormizd Monastery, named after its seventh-century founder Rabban Hormizd (Rabban means "monk"), who is venerated as a saint in the churches descended from the Church of the East, erroneously called the Nestorian.

The monastery, built on the mountain slope, was for the East Syrian Church of the East a centre of learning that stood against the neighbouring West Syrian (Syriac Orthodox Church) communities and monasteries. It was the burial place of the patriarchs of the Church of the East from the late fifteenth century and was their seat from the time of Shimun VI (1503-1538) until the end of the series of patriarchs known as the Eliya line.[11] Isolated and cut off by snow from Alqosh in winter, it never became their permanent residence,[12] and its line of patriarchs is commonly described as the Mosul line or as resident in Alqosh.[13]

In the schism of 1552, the abbot of the monastery, Yohannan Sulaqa, was elected irregularly to the post of patriarch by several bishops who were dissatisfied with the restriction of patriarchal succession to members of a single family. By tradition, a patriarch could be ordained only by someone of archiepiscopal (metropolitan) rank, a rank to which only members of that one family were promoted. For that reason, Sulaqa travelled to Rome, where, presented as the new patriarch elect, he entered communion with the Catholic Church and was ordained by the Pope and recognized as patriarch. He and his successors (who eventually formally broke communion with Rome) took up residence further east. This schism gave rise to the Chaldean Catholic Church, in opposition to what historians call the traditionalist wing of the Church of the East, that which in 1976 officially adopted the name "Assyrian Church of the East".[14][15]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the "legitimist" Alqosh patriarchal line from which Sulaqa broke away in 1552, drew closer to Rome, especially during the 58-year reign of Eliya XI/XII Denkha (1722−1778), who sent several letters to Rome, some with professions of faith in line with Catholic teaching, but no formal papal recognition followed.[16][17] However, it was a member of the family from whom the "legitimate" traditionalist patriarchs were chosen, Yohannan Hormizd (1760–1838) who, having considered himself a Catholic since 1778, was chosen as patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church in 1830.[18][17]

Association with the Prophet Nahum

Austen Henry Layard, who visited the area in 1847, reported that by "a very ancient tradition" the village contains the tomb of the prophet Nahum, whose Old Testament book begins with: "An oracle concerning Nineveh. The book of the vision of Nahum of Elkosh."[19] While Jerome located in Galilee the birthplace of Nahum, Layard considered not without weight the Alqosh tradition in spite of the lack of inscriptions or ancient remains.[20] Iraqi Jews made pilgrimage to the site during Shavuot, and "He who has not made the pilgrimage to Nahum's tomb has not yet known real pleasure" was a common saying.[21] When Jews were expelled from Iraq or voluntarily emigrated to Israel in 1948, the Jewish custodian entrusted the care of the building to a local Chaldean Catholic.[22] A survey conducted in 2017 determined that the structure was in danger of collapse, and in the following year work began on stabilizing it.[23][24][25][26][27]

Destruction

Other attacks

- The village was attacked and sacked by Timur (Tamerlane) in 1401 AD.[17]

- Alqosh was attacked in 1508 AD by Pasha of Baghdad Bar Yak (Murad Bey).[17]

- Soran Kurds attacked Alqosh, killing nearly 300 villagers in 1831.[28]

- Mosa Pasha, the governor of Amadiya, approached Alqosh and put fire to Rabban Hermizd Monastery in 1828 AD.[29]

- Mohammed Pasha (Mira Koor), the Kurdish prince of Rowanduz attacked Alqosh, killing over 600 of its inhabitants in 1832 AD.[29]

- Resoul Beck, Mira Koor's brother, repeated the attack in 1840 AD.[29]

- Rabban Hormizd Monastery was attacked by the Kurds, and 1000 manuscripts may have been destroyed.[28]

- In 2014, the terrorists associated with the radical Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) came close to Alqosh. Almost all of the people fled Alqosh; however, many men and youths did not leave Alqosh due to a desire to protect their town. ISIL failed to take the town after protection from the Assyrian militia,[30] Alqoshians and Kurdish Peshmerga fighters.[31]

Demographics

The town of Alqosh is primarily home to members of the Chaldean Catholic Church but has a smaller number of Yazidi inhabitants.[32] In 1913, the town of Alqosh, was according to Joseph Tfinkdji inhabited by 7,000 Chaldean Catholics.[33] Many have emigrated since the 1970s. It is estimated that at least 40,000 "Alqushnaye" immigrants and their 2nd and 3rd generation descendants now live in the cities of Detroit, Michigan, the western suburb of Fairfield in Sydney, Australia and San Diego, California.

In February 2010, the attacks against Assyrians in Mosul forced 4,300 Assyrians to flee from Mosul to the Nineveh plains where there is an Assyrian majority population. A report by the United Nations stated that 504 Assyrians at once migrated to Alqosh. Many Assyrians from Mosul and Baghdad since the post-2003 Iraq war have fled to Alqosh for safety. The town's population in 2020 is estimated to be roughly 4,600.[34]

In 2014 the mayor of Aqlosh, Faiz Jahwareh, was illegally detained and replaced by KDP member Lara Zara, only to be reinstated after protests by Alqosh residents.[35] Jahwareh was again detained and replaced by the KRG in July 2017 on the basis of false corruption charges that were dismissed by the Iraqi Federal Court.[36][37] Basim Bello, mayor of nearby Tel Keppe, was also unlawfully removed by the same parties in August 2017, and reinstated by order of the Governor of Nineveh in August 2018.[38][39]

Climate

Alqosh has a semi-arid climate (BSh) with extremely hot and dry summers, and cool wet winters.

| Climate data for Alqosh | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

14 (57) |

20 (68) |

26 (79) |

34 (93) |

38 (100) |

43 (109) |

40 (104) |

38 (100) |

30 (86) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

27 (81) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

4 (39) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

13 (55) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39 (1.5) |

69 (2.7) |

51 (2.0) |

27 (1.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (0.2) |

36 (1.4) |

60 (2.4) |

288 (11.3) |

| Average precipitation days | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 65 |

| Source: World Weather Online (2000-2012)[40] | |||||||||||||

`

Natives of Alqosh

- Yohannan Hormizd (1760–1838), Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church 1830–1838

- Joseph VI Audo (1790–1878), Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church 1847–1878

- Toma Audo (1854–1918), Archbishop of Urmia

- Yousef VI Emmanuel II Thomas (1852–1947), Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church 1900–1947

- Paul II Cheikho (1906–1989), Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church 1958–1989

- Hirmis Aboona (1940–2009), historian

- Emil Shimoun Nona (1967– ), Archbishop of Mosul 2009–2015, Eparch of Chaldean Catholic Eparchy of Saint Thomas the Apostle of Sydney 2015–

See also

References

- معاناة الكورد الايزديين فيá ظل الحكومات العراقية، 1921-2003. University of California, Berkeley, USA. 2008.

- Maclean, Arthur John (1901). Dictionary of the Dialects of Vernacular Syriac. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 13b.

- Payne Smith, Robert (1879–1901). Thesaurus Syriacus (in Latin). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 221.

- Thomas A. Carlson, “Alqosh — ܐܠܩܘܫ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified June 7, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/19.

- Ronald Sempill Stafford (1935). The Tragedy of the Assyrian Minority in Iraq. p. 187.

- Donabed, Sargon (1 March 2015). Reforging a Forgotten History. Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9780748686025.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-7486-8602-5.

- "Ny bas stärker NPU:s grepp om Nineveslätten". hujada.com. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Militias of Iraqi Christians resist Islamic State amid sectarian strife". Catholic Philly. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Kruczek, Gregory J. (13 December 2018). "Christian Minorities and the Struggle for Nineveh: The Assyrian Democratic Movement in Iraq and the Nineveh Plains Protection Units" (PDF). VTechWorks: 29.

- Zubaida, Sami (2000). "Contested Nations: Iraq and the Assyrians". Nations and Nationalism. 6 (3): 363–382. doi:10.1111/j.1354-5078.2000.00363.x. ISSN 1354-5078.

- List_of_Patriarchs_of_the_Church_of_the_East#Patriarchal lines from the schism of 1552 until 1830

- David Wilmshurst (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. Peeters Publishers. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-90-429-0876-5.

- F. Kristian Girling, "The Chaldean Catholic Church: A study in modern history, ecclesiology and church-state relations (2003–2013)" (Department of Theology, Heythrop College, University of London), p. 43

- Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- Eckart Frahm (24 March 2017). A Companion to Assyria. Wiley. p. 1132. ISBN 978-1-118-32523-0.

- Heleen L. Murre-Van Den Berg, "The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries" in Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies Volume 2 (1999 [2010), p. 247,

- David Wilmshurst (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913 (582 ed.). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9042908769.

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006). Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453–1923. Cambridge University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-521-02700-7.

- Nahum 1:1

- Austen Henry Layard (1849). Nineveh and Its Remains. J. Murray. p. 233.

- Neurink, Judit (5 July 2015). "Kurdistan needs help to preserve its Jewish heritage". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Hedow, Amer (3 August 2009). "An AlQosh Man Struggles to Keep a Promise to an Old Friend". chaldean.org. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Schwartzstein, Peter (19 February 2015). "Surrounded by Conflict, an Ancient Synagogue Crumbles in Iraq". National Geographic. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- "Progress made on saving Prophet Nahum's tomb in Iraq". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- Neurink, Judit (21 March 2018). "Hebrew prophet's tomb in Iraq saved from collapse". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- staff, T. O. I. "US to donate $500K to restore tomb of biblical prophet Nahum in Iraq". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- JTA. "Historic Jewish site outside Mosul said at risk of collapse". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Wilmhurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organization of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. p. 205.

- Geoff Hann, Karen Dabrowska, Tina Townsend-Greaves (2015). Iraq: The ancient sites and Iraqi Kurdistan. ISBN 1841624888.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Foundation, Thomson Reuters. "Iraq's traumatised minorities: test of unity after Mosul offensive". news.trust.org. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Costa-Roberts, Daniel (15 March 2015). "8 things you didn't know about Assyrian Christians". PBS. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- "UNPO: Assyria: Crowds Gather to Protest Mayor's Unfounded Expulsion". unpo.org. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Joseph Tfinkdji, "L'Église Chaldéenne Catholique autrefois et aujourd'hui", in Annuaire Pontifical Catholique 17 (1914). pp. 449-525.

- "Population Project". Shlama Foundation. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Iraqi Christians reject second mayor installed by pro-Kurd council". World Watch Monitor. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Post - Assyrian Policy Institute". assyrianpolicy. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- "Iraqi Christians reject second mayor installed by pro-Kurd council". World Watch Monitor. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- "Mayor of Tel Keppe Reinstated After Unlawful Dismissal by KDP". Assyrian Policy Institute. 8 August 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "Alqosh, Christian village on faultline of Iraq and Kurdistan". Middle East Eye. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- "Alqosh, Ninawa Monthly Climate Average, Iraq". World Weather Online. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Sources

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006) [1983]. Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Addai Scher, Notice sur les manuscrits syriaques conservés dans la bibliothèque du couvent des Chaldéens de Notre-Dame-des-Semences, Journal Asiatique Sér. 10: 8, 9 (1906). This may be found online at Gallica by searching for "Journal Asiatique". An English translation of the first portion is at tertullian.org