Cizre

Cizre (pronounced [ˈdʒizɾe]; Arabic: جزيرة ابن عمر, romanized: Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar,[3][nb 1] or Madinat al-Jazira,[8] Hebrew: גזירא, romanized: Gzira,[9] Kurdish: Cizîr,[10] or Cizîre,[11] Syriac: ܓܙܪܬܐ ܕܒܪ ܥܘܡܪ, romanized: Gāzartā,[3][nb 2]) is a city and district in Şırnak Province in southeastern Turkey. It is located on the river Tigris, by the Syria–Turkey border, and in the historical region of Upper Mesopotamia.

Cizre | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Cizre | |

Cizre | |

| Coordinates: 37°19′30″N 42°11′45″E | |

| Country | Turkey |

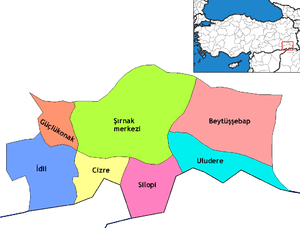

| Province | Şırnak |

| District | Cizre |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mehmet Ziriğ (HDP) |

| • Kaymakam | Davut Sinanoğlu |

| Area | |

| • District | 467.64 km2 (180.56 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 377 m (1,237 ft) |

| Population (2019)[2] | |

| • Urban | 125,799 |

| • District | 148,697 |

| • District density | 320/km2 (820/sq mi) |

| Post code | 73200 |

| Website | www.cizre.bel.tr |

In Kurdish culture, Cizre is presented as the setting of the tale of Mem and Zin.[14]

Etymology

The various names for the city of Cizre descend from the original Arabic name Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, which is derived from "jazira" ("island" in Arabic), "ibn" ("son of" in Arabic), and the name Umar, thus Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar translates to "island of Umar".[15] The city's alternative Arabic name Madinat al-Jazira is composed of "madinat" ("city" in Arabic) and "al-Jazira" ("the island" in Arabic), and therefore translates to "the island city".[16] Cizre was known in Syriac as Gāzartā d'Beṯ Zabdaï ("island of Zabdicene" in Syriac), from "gazarta" ("island" in Syriac) and "Beṯ Zabdaï" ("Zabdicene" in Syriac).[12]

History

Buyid 978–984

Marwanid 984–990

Uqaylid 990–???

Under Buyid suzerainty 990-996

Marwanid ???–1096

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Luluid 1251–1261

![]()

![]()

Bohtan 1336/1337–1456

![]()

Bohtan 1496–1847

![]()

![]()

![]()

Classical and early medieval period

Cizre is identified as the location of Ad flumen Tigrim, a river crossing depicted on the Tabula Peutingeriana, a Roman 4th/5th century map.[17] The river crossing lay at the end of a Roman road that connected it with Nisibis,[18] and was part of the region of Zabdicene.[19] It was previously assumed by most scholars that Bezabde was located at the same site of what would later become Cizre,[20] but is now agreed to be at Eski Hendek, 13 km (8.1 mi) northwest of Cizre.[21]

Cizre was originally known as Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, and was founded by and named after al-Hasan ibn Umar ibn al-Khattab al-Taghlibi (d. c. 865), Emir of Mosul, in the early 9th century, as recorded by Yaqut al-Hamawi in Mu'jam al-Buldan.[22][23] The city was constructed in a bend in the river Tigris, and al-Hasan ibn Umar built a canal across the bend, placing the city on an island in the river, hence the city's name.[24] Eventually, the original course of the river disappeared due to sedimentation and shifted to the canal, leaving the city on the west bank of the Tigris.[25] Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was situated to take advantage of trade routes from the direction of Amid to the northwest, Nisibin to the west, and Iran to the northeast.[26] The city also functioned as a river port, and goods were transported by raft down the Tigris to Mosul and further south.[27] Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar supplanted the neighbouring city of Bezabde as its inhabitants gradually left for the new city, and was likely abandoned in the early 10th century.[26]

Medieval Islamic scholars recorded competing theories of the founder of the city as al-Harawi noted in Ziyarat that it was believed that Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was the second city founded by Noah after the Great Flood.[8] This belief rests on the identification of nearby Mount Judi as the apobaterion (place of descent) of Noah's Ark.[28] Shahanshah Ardashir I of Iran (180-242) was also considered a potential founder.[22] In Wafayāt al-Aʿyān, Ibn Khallikan reported that Yusuf ibn Umar al-Thaqafi (d. 744) was considered by some to be responsible for the city's foundation, whilst he argued that Abd al-Aziz ibn Umar was the founder and namesake of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar.[23]

The city was fortified in the 10th century at the latest.[24] In the 10th century, Ibn Hawqal in Surat al-Ard described Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar as an entrepôt engaged in trade with the Eastern Roman Empire, Armenia, and the districts of Mayyafariqin, Arzen, and Mosul.[29]

Abu Taghlib, Hamdanid Emir of Mosul, allied himself with the Buyid Emir Izz al-Dawla Bakhtiyar of Iraq in his civil war against his cousin Emir 'Adud al-Dawla of Fars in 977 on the condition that Bakhtiyar hand over Abu Taghlib's younger brother Hamdan, who had conspired against him.[30] Although Abu Taghlib had secured his reign by executing his rival brother Hamdan, the alliance quickly backfired following Adud al-Dawla's victory over Abu Taghlib and Bakhtiyar at Samarra in the spring of 978 as he then annexed Hamdanid territory in upper Mesopotamia, and thus Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar came under Buyid rule, forcing Abu Taghlib to go into exile.[30][31] Buyid control of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was cut short by the civil war that followed the death of Adud al-Dawla in 983 as it allowed the Kurdish chief Bādh to seize Buyid territory in upper Mesopotamia in the following year, and he was acknowledged as its ruler by the claimant Emir Samsam al-Dawla.[32] Bādh attempted to conquer Mosul in 990, and the Hamdanid brothers Abu Abdallah Husayn and Abu Tahir Ibrahim were sent by the Buyid Emir Baha al-Dawla to repel the threat.[33] The Uqaylid clan agreed to aid the brothers against Bādh in return for the cities of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, Balad, and Nisibin, and Bādh was subsequently defeated and killed.[33] The leader of the Uqaylids Abu l-Dhawwad Muhammad ibn al-Musayyab secured control of the cities, and acknowledged Emir Baha al-Dawla as his sovereign.[33] On Muhammed's death in 996, his brother and successor as emir al-Muqallad asserted his independence, expelling the Buyid presence in the emirate, and thus ending Buyid suzerainty.[33]

High medieval period

Turkmen nomads arrived in the vicinity of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in the summer of 1042, and carried out raids in Diyar Bakr and upper Mesopotamia.[34] The Marwanid emirate became a vassal of the Seljuk Sultan Tughril in 1056.[35]

In the summer of 1083, the former Marwanid vizier Fakhr al-Dawla ibn Jahir persuaded the Seljuk Sultan Malikshah to send him with an army against the Marwanid emirate,[36] and eventually Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, the last remaining stronghold, was captured in 1085.[37][38] Although the Marwanid emirate was severely reduced, its final emir Nasir al-Dawla Mansur was permitted to continue to rule solely Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar under the Seljuk Sultanate from 1085 onwards.[39] The mamluk Jikirmish seized Mansur and usurped the emirate of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar on Mansur's death in January 1096.[40] In late 1096, Jikirmish set out to relieve Kerbogha's siege of Mosul following a request for aid from the Uqaylid Emir Ali ibn Sharaf al-Dawla of Mosul, but was defeated by Kerbogha's brother Altuntash, and submitted to him as a vassal.[40] Jikirmish was forced to aid in the ultimately successful siege against his former ally, and thus came under the suzerainty of Kerbogha as Emir of Mosul.[40] Kerbogha died in 1102, and Sultan Barkiyaruq appointed Jikirmish as his replacement as emir.[41] Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was thereafter directly ruled over by a string of Seljuk emirs of Mosul until the appointment of Zengi.[41]

Emir Aqsunqur al-Bursuqi of Mosul was murdered by assassins in 1126, and was succeeded by his son Mas'ud who died after several months and his younger brother became emir with the mamluk Jawali serving as atabeg (regent).[42] Jawali sent envoys to Sultan Mahmud II to receive official recognition for al-Bursuqi's son as emir of Mosul, but the envoys bribed the vizier Anu Shurwan to recommend Imad al-Din Zengi be appointed as emir of Mosul instead.[42] The sultan appointed Zengi as emir in the autumn of 1127, but he had to secure the emirate by force as forces loyal to al-Bursuqi's son resisted Zengi, and retained control of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar.[42] After taking Mosul, Zengi marched north and besieged Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar; in an attack, he ferried soldiers across the river whilst others swam to the city, and eventually the city surrendered.[43] Later, an Artuqid coalition of Da'ud of Hisn Kayfa, Timurtash of Mardin, and Ilaldi of Amid threatened Zengi's realm in 1130 whilst he campaigned in the vicinity of Aleppo in Syria, forcing him to return and defeat them at Dara.[44] After the battle, Da'ud marched on Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar and pillaged its surroundings, thus Zengi advanced to counter him, and Da'ud withdrew to the mountains.[44]

The dozdar (governor of the citadel) of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, Thiqat al-Din Hasan, was reported to have sexually harassed soldiers' wives whilst their husbands were on campaign, and thus Zengi sent his hajib (chamberlain) al-Yaghsiyani to handle the situation.[45] To avoid a rebellion, al-Yaghsiyani told Hasan he was promoted to dozdar of Aleppo, so he arranged to leave the city, but was arrested, castrated, and crucified by al-Yaghsiyani upon leaving the citadel.[45] The Jewish scholar Abraham ibn Ezra visited the city in November 1142.[46] On Zengi's death in 1146, his eldest son Sayf al-Din Ghazi I received the emirate of Mosul, including Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar,[47] and Izz al-Dīn Abū Bakr al-Dubaysī was appointed as the city's governor.[22] The city was transferred to Qutb al-Din Mawdud on his seizure of the emirate of Mosul after his elder brother Sayf al-Din's death in November 1149.[47]

The Grand Mosque of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was constructed in 1155.[48] After Qutb al-Din's death in September 1170, Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was inherited by his son and successor Sayf al-Din Ghazi II as emir of Mosul.[47] Michael the Syrian recorded that a Syriac Orthodox monastery was confiscated and the city's bishop Basilius was imprisoned in 1173.[49] Upon the death of Sayf al-Din Ghazi in 1180, Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was granted as an iqta' to his son Mu'izz al-Din Sanjar Shah within the emirate of Mosul, however, in late 1183, Sanjar Shah recognised Saladin as his suzerain, thus becoming a vassal of the Ayyubid Sultanate of Egypt, and effectively forming an autonomous principality.[47] Sanjar Shah continued to mint coins in his own name, and copper dirhams were minted at Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in 1203/1204.[50]

Sanjar Shah ruled until his murder by his son Ghazi in 1208 and was succeeded by his son Mu'izz al-Din Mahmud.[51] Mahmud successfully maintained Zengid control over Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar with the marriage of his son al-Malik al-Mas'ud Shahanshah to the daughter of Badr al-Din Lu'lu', who had overthrown the Zengids at Mosul and usurped power for himself in 1233.[51] The Grand Mosque of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was renovated during Mahmud's reign.[48] In the early 13th century, the city's fort and madrasa are attested by Ibn al-Athir in Al-Tārīkh al-bāhir fī al-Dawlah al-Atābakīyah bi-al-Mawṣil, and its mosque by Ibn Khallikan in Wafayāt al-Aʿyān.[23] According to the Arab scholar Izz al-Din ibn Shaddad, the Mongol Empire demanded 100,000 dinars in tribute from the ruler of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in 1251.[52] The end of the Zengid dynasty was heralded by the death of Mahmud in 1251 as Badr al-Din Lu'lu' had Mahmud's successor al-Malik al-Mas'ud Shahanshah killed soon after and assumed control of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar.[51]

Late medieval period

Badr al-Din Lu'lu' acknowledged Mongol suzerainty to secure his realm as early as 1252,[53] and minted coins in the name of Great Khan Möngke Khan in 1255 at the latest.[54] He is also known to have had a mosque built at Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar.[22] Badr al-Din became subject to the Mongol Ilkhanate on Hulagu Khan's assumption of the title Ilkhan (subject khan) in 1256.[55] Badr al-Din Lu'lu' died in July/August 1259,[53] and his realm was divided between his sons, and Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was bequeathed to his son al-Malik Al-Mujahid Sayf al-Din Ishaq.[56] The sons of Badr al-Din Lu'lu' chafed under Mongol rule and soon all had rebelled and travelled to Egypt seeking military assistance as al-Muzaffar Ala al-Din Ali left Sinjar in 1260,[56] al-Salih Rukn al-Din Ismail left Mosul in June 1261,[53] and finally Ishaq fled Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar for Egypt shortly afterwards.[57] Prior to his flight, Ishaq extorted 700 dinars from the city's Christians, and news of his impending escape pushed the populace to riot against his decision to leave the city to the wrath of the Mongols.[58]

In Ishaq's absence, 'Izz ad-Din 'Aibag, Emir of Amadiya, seized the city, and an attack by Abd Allah, Emir of Mayyafariqin, was repelled.[58] Baibars, Sultan of Egypt, refused to provide an army to the sons of Badr al-Din against the Mongols, but they were permitted to accompany Caliph Al-Mustansir on his campaign to reconquer Baghdad from the Mongols.[57] The three brothers marched with the caliph's campaign until they split at Al-Rahba, and travelled to Sinjar,[59] where Ali and Ishaq briefly remained whilst Ishaq continued onwards to Mosul, however, the two brothers abandoned Sinjar and Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar to the Mongols, and returned to Egypt upon learning of the caliph's death and defeat in November.[60] Mosul was sacked and Ismail was killed by a Mongol army after a siege from November to July/August 1262.[60] After the sack of Mosul, the Mongol army led by Samdaghu besieged Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar until the summer of 1263; the siege was lifted and the city spared when the Nestorian bishop Henan Isho claimed to have knowledge of chrysopoeia, and offered to render his services.[61] Jemal ad-Din Gulbag was appointed to govern Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, but he was later executed for conspiring with the city's former ruler Ishaq, and was replaced by Henan Isho,[61] who was also executed in 1268 following accusations of impropriety.[62]

In the second half of the 13th century, Mongol gold, silver, and copper coins were minted at Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar,[63] and production there increased after Khan Ghazan's (r. 1295-1304) reforms.[64] It was later attested that the vizier Rashid-al-Din Hamadani had planned to construct a canal from the Tigris by the city.[64] Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was visited by the Moroccan scholar Ibn Battuta in 1327 and noted the city's mosque, bazaar,[65] and three gates.[22] In 1326/1327, the city was granted as a fief to a Turkman chief, and Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar remained under his control until the disintegration of the Ilkhanate in 1335, soon after which it was seized by the Bohtan clan in 1336/1337 with the aid of al-Ashraf, Ayyubid Emir of Hisn Kayfa.[66] In the 1330s, Hamdallah Mustawfi in Nuzhat Al Qulub reported that Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar had an annual revenue of 170,200 dinars.[67] The emirate of Hisn Kayfa had aimed to control Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar through the Bohtan clan in providing military assistance to its capture and the marriage of a daughter to Izz ed-Din, Emir of Bohtan, but this was unsuccessful as the Bohtan emirate developed the city and consolidated their rule, and eventually the emir of Hisn Kayfa attempted to take Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar by force in 1384/1385, but was repelled.[66]

The emirate of Bohtan submitted to the Timurid Empire in 1400 after Timur sacked Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in retribution for the emir having seized one of his baggage convoys.[68] As punishment for the emir's refusal to participate in Timur's campaign in Iraq, the city was sacked by Timur's son Miran Shah.[68]

Early modern period

Uzun Hasan usurped leadership of the Aq Qoyunlu from his elder brother Jahangir in a coup at Amid in 1452, and set about expanding his realm by seizing Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in 1456, whilst the emir of Bohtan withdrew into the mountains.[69] Rebellion and civil war followed the death of Uzun Hasan in 1478, and the emir of Bohtan retook Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar from the Aq Qoyunlu in 1495/1496.[70]

Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar came under Safavid suzerainty in the first decade of the 16th century, but after the Ottoman victory at the battle of Chaldiran over Shah Ismail I in 1514, Sultan Selim I sent Idris Bitlisi to the city and he successfully convinced the emir of Bohtan to submit to the Ottoman Empire.[71] The emirate of Bohtan was incorporated into the empire as a hükûmet (autonomous territory),[14] and was assigned to the eyalet (province) of Diyarbekir upon its formation in 1515.[72] Sayyid Ahmad ruled in 1535.[22]

Christian families from Erbil found refuge and settled in Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in 1566.[22] In the mid-17th century, Evliya Çelebi visited Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar en route from Mosul to Hisn Kayfa,[73] and noted the city possessed four muftis and a naqib al-ashraf, and its qadis (judges) received a daily salary of 300 akçes.[74] In the late 17th century, Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar is mentioned by Jean-Baptiste Tavernier in Les Six Voyages de J. B. Tavernier as a location on the route to Tabriz.[75]

Late modern period

The Egyptian invasion of Syria in 1831-1832 allowed Mohammed Pasha Mir Kôr, Emir of Soran, to expand his realm, and he seized Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in 1833.[76][22] The Ottoman response to Mir Kôr was delayed by the war with Egypt until 1836, in which year Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was retaken by an army led by Reşid Mehmed Pasha.[76] Reşid deposed Saif al-Din Shir, Emir of Bohtan and mütesellim of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, and he was replaced by Bedir Khan Beg.[76] In 1838, an Ottoman army was sent to Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar during the campaign to suppress the rebellion of Abdul Agha and Khan Mahmud in the vicinity of Lake Van.[77][78] The German adviser Helmuth von Moltke the Elder accompanied the Ottoman army and reported back to the Ottoman government from Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in June 1838.[79] Bedir Khan reportedly established a munitions and arms factory at the city.[80]

In 1842, as part of the centralisation policies of the Tanzimat reforms, the kaza (district) of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was attached to the eyalet of Mosul, whilst the kaza of Bohtan, which constituted the remainder of the emirate, remained within the eyalet of Diyarbekir, thus administratively dividing the emirate, and provoking Bedir Khan.[78] The administrative reform aimed to increase Ottoman state revenue, but left the previously loyal emir disgruntled with the Ottoman state.[81] Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was visited by the American missionary Asahel Grant on 13 June 1843.[82] Bedir Khan's 1843 and 1846 massacres in Hakkari led the British and French governments to demand his removal from power,[80] and he was subsequently summoned to Constantinople, but Bedir Khan refused, and an Ottoman army was sent against him.[83] The emir defeated the Ottoman army, and he declared the independence of the Emirate of Bohtan.[80] Bedir Khan's success was brief as a large Ottoman army led by Osman Pasha, with Omar Pasha and Sabri Pasha, marched against him, and his relative Yezdanşêr defected and allowed for the Ottoman occupation of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar.[80] The Ottoman government unsuccessfully encouraged Bedir Khan to surrender, and the vali (governor) of Diyarbekir wrote to the Naqshbandi sheikhs İbrahim, Salih, and Azrail at Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar to mediate in June 1847.[84] Although Bedir Khan retook Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, the emir was forced to withdraw and surrendered on 29 July.[80][78]

As a consequence of Bedir Khan's rebellion, the emirate of Bohtan was dissolved and Yezdanşêr succeeded him as mütesellim of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar.[85] Also, the eyalet of Kurdistan was formed on 5 December 1847, and included the kazas of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar and Bohtan.[86] Yezdanşêr met with Lieutenant Colonel (later General) Fenwick Williams at Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in 1849 whilst he participated as the British representative in a commission to settle the Ottoman-Iranian border.[87] Yezdanşêr was soon replaced by the kaymakam Mustafa Pasha, sent away to Constantinople in March 1849, and forbidden from returning to Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar.[85] In 1852, the iane-i umumiye (temporary tax) was introduced, and the kaza of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was expected to provide 23,140 piastres.[88] During the Crimean War, in 1854, Yezdanşêr was ordered to recruit soldiers for the war, and 900 Kurds were recruited from Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar and Bohtan.[89] Yezdanşêr claimed to be maltreated by local officials and revolted in November, with Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar under his control.[89] He offered to surrender in January 1855 on the condition that he received the kazas of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar and Bohtan, but this was rejected.[90] An Ottoman army consisting of a regiment of infantry, a regiment of cavalry, and a battery of six guns was ordered to march on Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in February.[91] In March, Yezdanşêr accepted terms offered by General Williams, the British military commissioner with the Ottoman Anatolian army, and surrendered.[92]

In 1867, the eyalet of Kurdistan was dissolved and replaced by the Diyarbekir Vilayet, and Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar became the seat of a kaza in the sanjak of Mardin.[93] The kaza was subdivided into nine nahiyes, and possessed 210 villages.[94] Osman, son of Bedir Khan, seized Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in 1878 after his escape from captivity at Constantinople using demobilised Kurdish veterans of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, and proclaimed himself as emir.[95] The rebellion endured for eight months until it was quelled by an Ottoman army led by Shevket Bey.[96] The city was visited by the German scholar Eduard Sachau in 1880.[25] In the late 19th century, the French geographer Vital Cuinet recorded in La Turquie d'Asie the city's five caravanserais, one-hundred and six shops, ten cafés, and a vaulted bazaar.[22] At the inception of the Hamidiye cavalry corps in 1891, Mustafa, agha (chief) of the local Miran clan, enrolled and was made a commander with the rank of paşa, hereafter known as Mustafa Paşa.[97] Throughout the 1890s, Mustafa Paşa exploited his position to seize goods from merchants and plunder Christian villages in the district.[98] In 1892,[99] Mustafa Paşa converted a mosque at Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar into a barracks for his soldiers.[100]

The appointment of Mehmed Enis Paşa as vali of Diyarbekir on 4 October 1895 was quickly followed by massacres of Christians throughout the province,[101] and in mid-November an Ottoman army repelled an attempt by Mustafa Paşa to enter the city and slaughter its Christian inhabitants.[102] Mustafa Paşa subsequently complained to Enis Paşa, and the officer in charge of the regiment was summoned to Diyarbekir.[102] Later, the British and French vice-consuls at Diyarbekir, Cecil Marsham Hallward and Gustave Meyrier, respectively, suspected that Enis Paşa was responsible for the massacres in the province.[103] In 1897, the British diplomat Telford Waugh reported that Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was used as a place of exile by the Ottoman Empire as he noted the presence of Albanians deported there, and that the city's governor Faris, agha of the Şammar clan, had been exiled there after his fall from grace.[104]

Early 20th century

Mustafa Paşa feuded with agha Muhammad Aghayê Sor, and in 1900 the kaymakam of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar intervened to aid the Tayan clan, Mustafa Paşa's allies, against Aghayê Sor.[99] Several months later, Mustafa Paşa had twenty villages in the district loyal to his rival destroyed, and Aghayê Sor wrote to the Brigadier General Bahaeddin Paşa seeking protection.[99] Bahaeddin Paşa travelled to Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar to conduct an inquiry, but was imprisoned there for five days by Mustafa Paşa,[99] and the two rivals continued to attack each other's territories until Mustafa Paşa was assassinated on Aghayê Sor's orders in 1902.[105] Within the kaza of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, in 1909, there were 1500 households, 1000 of which possessed over 50 dönüms.[106] As late as 1910, the Miran clan annually migrated from their winter pastures in the plain of Mosul to Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in the spring to trade and pay taxes, and then across the Tigris to summer grazing grounds at the source of the river Botan.[107][108] The British scholar Gertrude Bell visited the city in May 1910.[109]

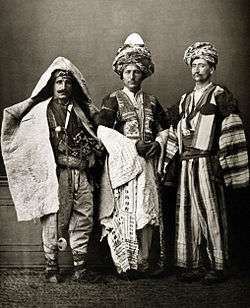

_2.434_Diyarbekir_Vilayet.jpg)

In 1915, amidst the ongoing genocide of Armenians and Assyrians perpetrated by the Ottoman government and local Kurds, Aziz Feyzi and Zülfü Bey carried out preparations to destroy the Christian population of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar on orders from Mehmed Reshid, vali of Diyarbekir.[110] From 29 April to 12 May, the officials toured the district and incited the Kurds against the Christians;[111] Halil Sâmi, kaymakam of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar since 31 March 1913, was replaced by Kemal Bey on 2 May 1915 due to his refusal to support the plans for genocide.[112] At this time, two redif (reserve) battalions were stationed in the city.[94] Julius Behnam, Syriac Orthodox Archbishop of Gazarta, fled to Azakh upon hearing of the commencement of massacres in the province in July.[94] Christians in rural areas of the district were massacred over several days from 8 August onwards,[112] and several Jacobite and 15 Chaldean Catholic villages were destroyed.[94]

On the night of 28 August, Flavianus Michael Malke, Syriac Catholic Bishop of Gazarta, and Philippe-Jacques Abraham, Chaldean Catholic Bishop of Gazarta, were killed.[113] On 29 August, Aziz Feyzi, Ahmed Hilmi, Mufti of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, and Ömer, agha of the Reman clan, coordinated the arrest, torture, and execution of all Armenian men and a number of Assyrians in Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar.[112][110] The men's bodies were dumped in the Tigris, and, two days later, the children were abducted into Muslim households, and most women were raped and killed, and their bodies were also thrown into the river.[110] Walter Holstein, German vice-consul at Mosul, reported the massacre to the German embassy at Constantinople on 9 September, and the German ambassador Ernst II, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg informed the German Foreign Office on 11 September that the massacre had resulted in the death of 4750 Armenians (2500 Gregorians, 1250 Catholics, and 1000 Protestants) and 350 Assyrians (250 Chaldeans and 100 Jacobites).[110] After the massacre, eleven churches and three chapels were confiscated.[94] 200 Armenians from Erzurum were exterminated near Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar by General Halil Kut on 22 September.[112] Kemal Bey continued in the office of kaymakam until 3 November 1915.[112]

In the aftermath of Ottoman defeat in the First World War, Ali İhsan Sâbis, commander of the Ottoman Sixth Army, was reported to have recruited and armed Kurds at Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in February 1919 in an effort to prevent British occupation.[114] After the murder of Captain Alfred Christopher Pearson, assistant political officer at Zakho, by Kurds on 4 April 1919, the occupation of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was considered to ensure the security of British Iraq, but ultimately dismissed.[115] Ahmed Hilmi, Mufti of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, was ordered to be arrested in May 1919 for his role in the massacre in 1915 as part of the Turkish courts-martial of 1919–1920, but he evaded arrest as he was under the protection of local Kurdish clans.[116]

Appeals from Kurds to the British government to create an independent Kurdish state spurred the appointment of Nihat Anılmış as commander at Cizre in June 1920 with instructions from the Prime Minister of Turkey Mustafa Kemal to establish local government and secure control of local Kurds by inciting them to engage in armed clashes against British and French forces, thus preventing good relations.[117] Local Kurdish notables complained to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey of alleged illegal activity by Nihat Anılmış, and although it was decided no action was to be taken in July 1922,[118] he was transferred away from Cizre in early September.[119]

Turkey concentrated a significant number of forces at Cizre in January 1923 to bolster the Turkish position at the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23.[120] The city itself was retained by Turkey, but part of the kaza was transferred to Syria and Iraq after the partition of the Ottoman Empire.[121] In response to Kurdish revolts in the 1920s, the Turkish government aimed to Turkify the population of eastern Turkey, but Christians were deemed unsuitable, and thus attempted to eradicate those who had survived the genocide.[122] In this effort, 257 Syriac Orthodox men from Azakh and neighbouring villages were imprisoned by the government at Cizre in 1926, where they were beaten and denied food.[122]

Late 20th century and contemporary period

Cizre received electricity and running water in the mid-1950s.[123] In the 1960s, the infrastructure of the city was developed as a new bridge, municipal buildings, and new roads were constructed and streets were widened, and amenities such as a public park named after Atatürk and a cinema were built.[123]

Roughly 60 people were detained and tortured for 20 days by Turkish police after the killing of two Turkish policemen in Cizre on 13 January 1989.[124] The economy of Cizre was severely disrupted by the eruption of the Gulf War as trade with Iraq was embargoed and the border was closed, resulting in the closure of 90% of shops in the city.[123] Kurdish militants clashed with Turkish security forces in Cizre on 18 June 1991, and five Turkish soldiers and one militant were killed, according to official reports, however Amnesty International reported the death of one civilian also.[124] On 21 March 1992, a pro-PKK demonstration to celebrate Nowruz in contravention of a state ban was dispersed by Turkish soldiers, and led to violence as Kurdish militants retaliated, resulting in the death of 26-30 people.[125] Properties in Cizre were damaged by Turkish soldiers in two shootouts against PKK militants in August and September 1993, and three militants were killed.[126]

Riots erupted in Cizre in October 2014 in response to the Turkish government's decision to prohibit Kurds from travelling to Syria to participate in the Syrian Civil War.[127] It is claimed that 17 Kurds from Cizre fought and died in the Siege of Kobanî.[128] The YDG-H, the militant youth wing of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), subsequently erected blockades, ditches, and armed checkpoints, and carried out patrols in several neighbourhoods to block the movement of Turkish police.[127][129] A military operation was launched by the Turkish Armed Forces to reestablish control over the city on 4 September 2015, and a curfew was imposed.[130] An estimated 70 YDG-H militants responded with rocket-propelled and grenade attacks on Turkish soldiers.[130][131] In the operation, the Turkish Ministry of the Interior claimed 32 PKK militants and 1 civilian had been killed, whereas the HDP argued 21 civilians were killed.[131] On 10 September, a group of 30 HDP MPs led by leader Selahattin Demirtaş were denied entry to the city by the police.[130] The curfew was briefly relaxed on 11 September, but was reimposed after two days.[132]

On 14 December 2015, Turkish military operations resumed in Cizre, and the curfew was renewed.[133] The military operation continued until 11 February, but the curfew was maintained until 2 March.[134] During the clashes between 24 July 2015 and 30 June 2016 at Cizre, the Turkish Armed Forces claimed 674 PKK militants were killed or captured, and 24 military and police officers were killed.[135] The Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects reported that four neighbourhoods were completely destroyed, with 1200 buildings severely damaged and approximately 10,000 buildings damaged, and c. 110,000 people fled the district.[136] The Turkish government announced plans in April 2016 to rebuild damaged 2700 houses in a project estimated to cost 4 billion Turkish lira.[137] The Turkish physician Dr Şebnem Korur Fincanci was arrested and imprisoned on charges of involvement in the propaganda of terrorism by the Turkish government on 20 June 2016 as a consequence of her report on conditions in Cizre after the end of the curfew in March 2016; she was later acquitted in July 2019.[138][139]

On 26 August 2016, 11 policemen were killed and 78 people were injured by a car bomb at a police checkpoint planted by the PKK, and the nearby riot police headquarters was severely damaged.[140] The Turkish government banned journalists and independent observers from entering the city to report on the attack.[141]

Ecclesiastical history

East Syriac

At the city's foundation in the early 9th century, it was included in the diocese of Qardu,[26] a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Nisibis in the Church of the East.[142] In c. 900, the diocese of Bezabde was moved and renamed to Gazarta (Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in Syriac), and partially assumed the territory of the diocese of Qardu,[26] which was also moved and renamed to its new seat Tamanon, having previously been based at Penek.[143] Tamanon declined and at some point after the mention of its last bishop in 1265, its diocese was subsumed into the diocese of Gazarta.[144]

Eliya was archbishop of Gazarta and Amid in 1504.[145]

Gazarta was a prominent centre of manuscript production, and most surviving east Syriac manuscripts from the late 16th century were copied there.[146]

The Catholic Church of Mosul, later known as the Chaldean Catholic Church, split from the Church of the East in the schism of 1552, and its inaugural patriarch Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa appointed Abdisho as archbishop of Gazarta in 1553.[147] Shemon VII Ishoyahb, Patriarch of the Church of the East, appointed Joseph as archbishop of Gazarta in response in 1554.[147][148] Abdisho succeeded Sulaqa as patriarch on his death in 1555.[147]

Gabriel was Nestorian archbishop of Gazarta in 1586.[149] There was an archbishop of Gazarta named John in 1594.[150] Joseph was Nestorian archbishop of Gazarta in 1610.[151] A certain Joseph, archbishop of Gazarta, is mentioned in a manuscript in 1618 with the patriarch Eliya IX.[152] A Nestorian archbishop of Gazarta named Joseph is also mentioned in a manuscript in 1657.[152]

Joseph, Nestorian archbishop of Gazarta, resided at the village of Shah in 1822.[153] A Nestorian archbishop named Joseph had two suffragan bishops, and served until his death in 1846.[154]

In 1850, the Nestorian diocese of Gazarta had 23 villages, 23 churches, 16 priests, and 220 families,[155] whereas the Chaldean diocese of Gazarta had 7 villages, 6 churches, 5 priests, and 179 families.[156] The Chaldean Catholic Church expanded considerably in the second half of the 19th century, and consequently its diocese of Gazarta grew to 20 villages, 15 priests, and 7,000 adherents in 1867.[156] The Chaldean diocese decreased to 5200 adherents, with 17 churches and 14 priests, in 1896, but recovered by 1913 to 6400 adherents in 17 villages, with 11 churches and 17 priests.[157]

West Syriac

The Syriac Orthodox diocese of Gazarta was established in 864, and is first mentioned under the authority of the maphrian in the tenure of the maphrian Dionysius I Moses (r. 1112–1142).[158]

Iwanis was the Syriac Orthodox Bishop of Gazarta in 1040.[13] Basilius was Syriac Orthodox Bishop of Gazarta in 1173.[49] John Wahb was bishop of Gazarta from his ordination by Gregory bar Hebraeus, Maphrian of the East, in 1265, to his death in 1280.[159] Dioscorus Gabriel of Bartella was consecrated bishop of Gazarta in 1284 by Gregory bar Hebraeus, and served in the office until his death on 7 September 1300.[160] 'Abd Allah of Bartella was archbishop of Gazarta in 1326.[160] Dioscorus Simon was Syriac Orthodox Archbishop of Gazarta until his death in 1501.[161] The Maphrian Baselios Yeldo consecrated George as archbishop of Gazarta in 1677, who assumed the name Dioscorus, and held the office until he was elevated to maphrian in 1684.[162] Behnam of Aqra was made archbishop of Gazarta at the church of Umm al-Zunnar in Homs in 1871 by the Patriarch Ignatius Peter IV, and assumed the name Julius.[163] He was represented by Iywannis Shakir, archbishop of Mosul, at the synod at the Monastery of Saint Ananias in 1916 to elect a new patriarch,[164] and served until his death in 1927.[163]

There was a Syriac Orthodox church of Mar Behnam at Gazarta in 1748, in which year Gregorius Tuma, Syriac Orthodox Archbishop of Jerusalem, was buried there.[162] There were 19 villages in the Syriac Orthodox diocese of Azakh and Gazarta in 1915.[165]

Government

Demography

Population

Until 1915, Cizre had a diverse population of Christian Armenians and Assyrians, who constituted half of the city's population, Jews, and Muslim Kurds.[94][170] The genocide of Armenians and Assyrians reduced the city's population significantly,[22] and it declined further with the departure of the Jews in 1950–1951.[171] The population began to recover in the second half of the 20th century,[22] and later increased dramatically from 1984 onwards due to the Kurdish–Turkish conflict as thousands of people fled to Cizre to escape pressure from both the Turkish armed forces and PKK militants.[126]

-

Year District Urban Rural Reference 1850 c. 4000 [172] 1890 9560 [22] 1918 c. 7500 [18] 1940 5575 [22] 1960 6473 [22] 1980 20,200 [126] 1990 63,626 50,023 13,603 [173] -

Year District Urban Rural Reference 2000 82,042 69,591 12,451 2007 105,651 90,477 15,174 [174] 2008 110,267 94,076 16,191 [175] 2009 113,041 96,452 16,589 [176] 2010 117,429 100,478 16,951 [177] 2011 122,967 104,844 18,123 [178] 2012 124,804 106,831 17,973 [179] -

Year District Urban Rural Reference 2013 129,578 110,166 19,412 [180] 2014 132,857 112,973 19,884 [181] 2015 131,816 111,266 20,550 [182] 2016 133,908 112,919 20,989 [183] 2017 140,372 [2] 2018 143,124 [2] 2019 148,697 125,799 22,898 [2]

Religion

Christian population

According to the census carried out by the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, 4281 Armenians inhabited the kaza of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar in 1913, with only one functioning church: 2716 Armenians in Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar itself and eleven nearby villages, and 1565 Armenians were nomadic.[184][112] Prior to the First World War, the kaza of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar contained 994 Syriac Orthodox (Jacobite) families in 26 villages, according to the report submitted to the Paris Peace Conference by the Syriac Orthodox Church in July 1919.[185]

60 Chaldean Catholic families inhabited the city in 1850, and were served by one church and one priest.[172] 300 Chaldeans in 1865, 240 Chaldeans in 1880, 320 Chaldeans in 1888, 350 Chaldeans in 1890, and 600 Chaldeans, with 2 priests and 2 churches, in 1913.[172]

In 1918, it was reported Kurds made up the majority of the city, with approximately 500 Chaldeans.[18] There were 960 Assyrians at Cizre in 1918.[186] In total, 35 Assyrian villages in the vicinity of Cizre were destroyed in the genocide.[187] 7510 Syriac Orthodox Christians were killed, including 8 clergymen, and 13 churches and convents were destroyed, in the district.[188]

At the Paris Peace Conference, the British authorities submitted a memorandum on behalf of the Nestorian patriarch Shimun XX Paulos requesting Cizre become part of an independent Assyrian state.[189]

Jewish population

The Jewish community of Cizre is attested by Benjamin of Tudela in the mid-12th century,[4] and he noted the city was inhabited by 4000 Jews led by rabbis named Muvhar, Joseph, and Hiyya.[8] J. J. Benjamin remarked on the presence of 20 Jewish families in Cizre during his visit in 1848.[190][191] Jews of Cizre spoke Judaeo-Aramaic and Kurdish.[171][192] There were 10 Jewish households in Cizre when visited by Rabbi Yehiel Fischel in 1859, and were described as very poor.[193] 126 Jews inhabited Cizre in 1891, as recorded by the Ottoman census.[194] The community had grown to 150 people by 1906,[195] and the synagogue was renovated in 1913.[196] In 1914, 234 Jews inhabited Cizre.[170] The Jewish community of Cizre emigrated to Israel in 1950–1951.[171] The Israeli politician Mickey Levy is a notable descendant of the Jews of Cizre.[192]

Culture

Education

Cizre formerly played a significant role in the dissemination of Islamic education in Upper Mesopotamia.[22] In the 11th century, a madrasa was constructed by the Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk.[197] In the following century, there were four Shafi‘i madrasas, and two Sufi khanqahs outside the city walls.[22] The two Sufi khanqahs were noted by Izz al-Din ibn Shaddad in the 13th century, and he also recorded the names of the four Shafi‘i madrasas as Ibn el-Bezri Madrasa, Zahiruddin Kaymaz al-Atabegi Madrasa, Radaviyye Madrasa and Kadi Cemaleddin Abdürrahim Madrasa.[198]

Until 1915, French Dominican priests operated a Chaldean Catholic school and Syriac Catholic school in the city, as well as other schools of those denominations in the vicinity.[94]

Monuments

Religious

In the 12th century, there was a bimaristan (hospital), 19 mosques, 14 hammams (baths), and 30 sabils (fountains).[22] This increased to two bimaristans, two grand mosques, 80 mosques, and 14 hammams when recorded by Ibn Shaddad in the next century.[198]

Secular

After the dissolution of the emirate of Bohtan in 1847, Bırca Belek, the citadel of Cizre, was periodically used as a barracks by Turkish soldiers, and was closed to the public.[199] It remained in military use, and was used by Turkish border guards from 1995 onwards, until 2010.[199] Excavations by archaeologists from Mardin Museum began in May 2013,[200] and continued until December 2014.[201]

Geography

Cizre is located at the easternmost point of the Tur Abdin in the Melabas Hills (Syriac: Turo d-Malbash, "the clothed mountain"), which is roughly coterminous with the region of Zabdicene.[19]

Climate

Cizre has a mediterranean climate (Csa in the Köppen climate classification) with wet, mild, rarely snowy winters and dry, extremely hot summers. Cizre has a mean temperature of 6.9 °C in coldest month and a mean temperature of 32.8 °C (91.0 °F) in hottest month. The highest temperature ever recorded in Cizre was 49 °C (120 °F), which is the highest temperature ever recorded in Turkey.[203]

| Climate data for Cizre, Turkey | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

29.8 (85.6) |

37.2 (99.0) |

41.7 (107.1) |

41.3 (106.3) |

37.3 (99.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

14.4 (57.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

19.5 (67.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

13.0 (55.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 118 (4.6) |

120 (4.7) |

109 (4.3) |

97 (3.8) |

42 (1.7) |

4 (0.2) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

34 (1.3) |

72 (2.8) |

127 (5.0) |

725 (28.4) |

| Source: Levoyageur[204] | |||||||||||||

Notable people

- Ismail al-Jazari (1136–1206), scholar

- Majd ad-Dīn Ibn Athir (1149–1210), historian

- Ali ibn al-Athir (1160–1233), historian

- Abdisho IV Maron (r. 1555–1570), Chaldean Catholic Patriarch of Babylon

- Malaye Jaziri (1570–1640), Kurdish poet

- Bedir Khan Beg (1803–1868), Emir of Bohtan

- Şerafettin Elçi (1938-2012), Kurdish politician

- Tahir Elçi (1966-2015), Kurdish lawyer

- Halil Savda (b. 1974), Kurdish conscientious objector

- Leyla İmret (b. 1987), Kurdish politician

References

Notes

Citations

- "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- "CİZRE NÜFUSU, ŞIRNAK". Türkiye Nüfusu (in Turkish). Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Carlson, Thomas A. (9 December 2016). "Gazarta". The Syriac Gazetteer. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Şanlı (2017), p. 72.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 352.

- Çetinoğlu (2018), p. 178.

- Kieser (2011), p. 139.

- Gil (2004), p. 428.

- Sabar (2002), p. 121.

- Avcýkýran, Dr. Adem, ed. (2009). "Kürtçe Anamnez, Anamneza bi Kurmancî" (PDF). Tirsik. p. 57. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Biner (2019), p. x.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 112.

- Palmer (1990), p. 257.

- Henning (2018), p. 94.

- Rassi (2015), p. 50.

- Gil (2004), p. 624.

- Roaf, M., T. Sinclair, S. Kroll, St J. Simpson. "Places: 874296 (Ad flumen Tigrim)". Pleiades. Retrieved 22 March 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Henning (2018), p. 88.

- Palmer (1990), p. xix.

- Lightfoot (1981), p. 86.

- Crow (2018), p. 235.

- Elisséeff (1986), pp. 960-961.

- ul-Hasan (2005), pp. 40-41.

- Nicolle (2013), p. 227.

- Lightfoot (1981), pp. 88-89.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 353.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 385.

- Zawanowska (2019), p. 36.

- Kennedy (2011), p. 180.

- Canard (1986), p. 128.

- Busse (2008), p. 269.

- Kennedy (2004), p. 260.

- Kennedy (2004), pp. 295-296.

- Beihammer (2017), p. 64.

- El-Azhari (2016), p. 42.

- Ibn al-Athir, pp. 209-210

- Ibn al-Athir, p. 221

- Beihammer (2017), p. 249.

- Hillenbrand (1991), p. 627.

- Ibn al-Athir, p. 286

- Cahen (1969), pp. 169-170.

- El-Azhari (2016), pp. 17-18.

- El-Azhari (2016), p. 44.

- El-Azhari (2016), p. 46.

- El-Azhari (2016), pp. 120-121.

- Gil (2004), p. 471.

- Heidemann (2002), pp. 453-454.

- Kana’an (2013), p. 189.

- Snelders (2010).

- "Zangid (Jazira) Sanjar 1203-1204". The David Collection. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Kana’an (2013), pp. 187-188.

- Jackson (2017), p. 252.

- Humphreys (1977), p. 468.

- Pfeiffer (2013), p. 134.

- Boyle (2007), p. 345.

- Patton (1991), p. 99.

- Amitai-Preiss (2004), p. 57.

- Bar Hebraeus XI, 518

- Amitai-Preiss (2004), p. 58.

- Amitai-Preiss (2004), p. 60.

- Bar Hebraeus XI, 520

- Bar Hebraeus XI, 525

- James (2019), p. 30.

- Sinclair (2019), p. 647.

- Miynat (2017), p. 94.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 401.

- Miynat (2017), p. 86.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 402.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 404.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 405.

- Bruinessen & Boeschoten (1988), pp. 14-15.

- Özoğlu (2004), p. 49.

- Bruinessen & Boeschoten (1988), p. 7.

- Bruinessen & Boeschoten (1988), pp. 26-27.

- Touzard (2000).

- Ateş (2013), pp. 67-68.

- Jwaideh (2006), p. 63.

- Özoğlu (2001), p. 397.

- Özoğlu (2001), p. 408.

- Jwaideh (2006), pp. 72-73.

- Özoğlu (2001), p. 398.

- Taylor (2007), p. 285.

- Henning (2018), p. 100.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 37.

- Badem (2010), pp. 362-363.

- Ateş (2013), p. 85.

- Badem (2010), p. 370.

- Badem (2010), p. 364.

- Badem (2010), p. 367.

- Badem (2010), p. 368.

- Badem (2010), p. 371.

- Badem (2010), p. 373.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), pp. 172, 337.

- Ternon (2002), pp. 179-180.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 410.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 256.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 156.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), pp. 160-161.

- Klein (2011), p. 71.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 162.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), pp. 102, 104.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 135.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 129.

- Henning (2018), p. 89.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 170.

- Quataert (1994), p. 865.

- Lightfoot (1981), p. 116.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 158.

- Lightfoot (1981), p. 117.

- Üngör (2012), pp. 98-99.

- Kévorkian (2011), p. 360.

- Kévorkian (2011), p. 378.

- Rhétoré (2005), pp. 290, 340.

- Jwaideh (2006), p. 134.

- Jwaideh (2006), p. 148.

- Üngör & Polatel (2011), p. 153.

- Mango (2013), pp. 5, 12-13.

- Mango (2013), p. 13-14.

- Burak (2005), p. 169.

- Ali (1997), p. 524.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 27.

- Sato (2001), pp. 62-63.

- Marcus (1994), p. 17.

- "Alleged Extrajudicial Executions in the Southeast - Four Further Cases" (PDF). Amnesty International. 26 February 1992. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "26 Are Killed as Kurds Clash With Turkish Forces". The New York Times. 22 March 1992. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Marcus (1994), p. 18.

- Salih, Cale; Stein, Aaron (20 January 2015). "How Turkey misread the Kurds". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Turkey and its Kurds: Dreams of self rule". The Economist. 12 February 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "PKK Youth: Fighting for Kurdish Neighbourhoods". Vice News. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "At least 30 killed in Kurdish town of Cizre: Ministry". Middle East Eye. 11 September 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Pamuk, Humeyra (27 September 2015). "A new generation of Kurdish militants takes fight to Turkey's cities". Reuters. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Bozarslan, Mahmut (13 September 2015). "Turkey imposes new curfew in battered Cizre". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Bowen, Jeremy (23 May 2016). "Inside Cizre: Where Turkish forces stand accused of Kurdish killings". BBC News. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "Turkey: State Blocks Probes of Southeast Killings". Human Rights Watch. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Over 12,000 killed or wounded during Turkey's security operations in Kurdish areas in 2015-2016". Nordic Monitor. 11 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "YIKILAN KENTLER RAPORU" (PDF) (in Turkish). Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects. September 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Emen, İdris (9 April 2016). "Project to renew 2,700 buildings in clash-hit Cizre to cost $1.3 billion". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Gupta, Sujata (6 December 2019). "What happens when governments crack down on scientists just doing their jobs?". Science News. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Case History: Sebnem Korur Fincanci". Front Line Defenders. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Turkey PKK conflict: Cizre bomb kills 11 policemen". BBC News. 26 August 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Kiley, Sam (27 August 2016). "Why Turkey Has Banned Reporting On Cizre Bombing". Sky News. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 38.

- Wilmshurst (2000), pp. 40, 100.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 396.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 50.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 241.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 22.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 351.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 260.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 86.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 352.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 195.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 136.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 83.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 368.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 361.

- Wilmshurst (2000), p. 362.

- Mazzola (2019), pp. 399-413.

- Ignatius Jacob III (2008), p. 214.

- Ignatius Jacob III (2008), p. 215.

- Barsoum (2003), p. 546.

- Ignatius Jacob III (2008), p. 216.

- Ignatius Jacob III (2008), pp. 217-218.

- Barsoum (2008), p. 51.

- Yacoub (2016), p. 60.

- "Seyyit Haşim Haşimi Biyografisi". Haberler.com. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Marcus (1994), p. 16.

- Sweeney, Steve (12 March 2020). "Turkish police detain HDP co-mayor of Kurdish city". The Morning Star. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Mayor of Cizre released from custody". Firat News Agency. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Karpat (1985), pp. 134-135.

- Mutzafi (2008), p. 10.

- Wilmshurst (2000), pp. 112-113.

- "1990 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2007 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2008 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2009 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2010 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2011 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2012 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2013 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2014 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2015 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "2016 Census Data" (in Turkish). Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Kévorkian (2011), p. 276.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), pp. 244-245.

- Yacoub (2016), p. 211.

- Yacoub (2016), p. 131.

- Yacoub (2016), p. 136.

- Yacoub (2016), p. 87.

- Zaken (2007), p. 11.

- Benjamin (1859), p. 65.

- Abdullah, Hemin (30 March 2015). "Şırnaklı Yahudi parlamenter: Kürdistan bağımsız olacak!". Rudaw (in Kurdish). Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Zaken (2007), p. 215.

- Courtois (2013), p. 122.

- Galante (1948), p. 28.

- Şanlı (2017), p. 74.

- Boyle (2007), p. 216.

- Açıkyıldız Şengül (2014), p. 182.

- "Birca Belek örneğinde sömürgecilik". Firat News Agency (in Turkish). 21 August 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Kozbe, Gulriz – Alp, Mesut– Erdoğan, Nihat (9–13 June 2014). "The Excavatıons in the Cıtadel of Cızre Castle (Bırca Belek)" (PDF). 9. International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. p. 77. Retrieved 16 April 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "Cizre'deki Kazılarda Osmanlı'ya Ait Eserler Çıktı". Haberler (in Turkish). 17 May 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Polat, Veysi (11 December 2015). "Cizrespor'da "güvenlik" isyanı; ligden çekildiler!". T24 (in Turkish). Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Türkiye'de ve Dünyada Kaydedilen En Düşük ve En Yüksek Değerler". Turkish State Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- TURKEY - CIZRE : Climate, weather, temperatures

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Gregory bar Hebraeus (1932). Chronography. Translated by E. A. W. Budge. Oxford University Press.

- Ibn al-Athir (2002). The Annals of the Saljuq Turks: Selections from al-Kamil fi'l-Ta'rikh of Ibn al-Athir. Translated by D.S. Richards. Routledge.

Secondary sources

- Açıkyıldız Şengül, Birgül (2014). "Cizre Kırmızı Medrese:Mimari, İktidar ve Tarih". Kebikeç (in Turkish). 38: 169–198.

- Ali, Othman (1997). "The Kurds and the Lausanne Peace Negotiations, 1922-23". Middle Eastern Studies. 33 (3): 521–534.

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (2004). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260-1281. Cambridge University Press.

- Ateş, Sabri (2013). Ottoman-Iranian Borderlands: Making a Boundary, 1843–1914. Cambridge University Press.

- Badem, Candan (2010). The Ottoman Crimean War (1853-1856). Brill.

- Barsoum, Ephrem (2003). The Scattered Pearls: A History of Syriac Literature and Sciences. Translated by Matti Moosa. Gorgias Press.

- Barsoum, Ephrem (2008). History of the Za‘faran Monastery. Translated by Matti Moosa. Gorgias Press.

- Beihammer, Alexander Daniel (2017). Byzantium & Emergence of Muslim-Turkish Anatolia, c.1040-1130. Routledge.

- Benjamin, Israel Joseph (1859). Eight years in Asia and Africa from 1846-1855. Routledge.

- Biner, Zerrin Ozlem (2019). States of Dispossession: Violence and Precarious Coexistence in Southeast Turkey. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Boyle, J. A. (2007). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods. Cambridge University Press.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2017). "A Historical Note of October 1915 Written in Dayro D-Zafaran (Deyrulzafaran)". In David Gaunt; Naures Atto; Soner O. Barthoma (eds.). Let Them Not Return: Sayfo – The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Berghahn Books. pp. 148–157.

- Bruinessen, Martin Van; Boeschoten, Hendrik (1988). Evliya Çelebi in Diyarbekir. Brill.

- Burak, Durdu Mehmet (2005). "EL-CEZİRE KUMANDANI NİHAT PAŞA'NIN EŞKIYA TARAFINDAN SOYULMASI" (PDF). Gazi Üniversitesi Kırşehir Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi (in Turkish). 6 (1): 169–183.

- Busse, Heribert (2008). "Iran Under the Buyids". In Richard Nelson Frye (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge University Press. pp. 250–305.

- Cahen, Claude (1969). "The Turkish Invasion: The Selchukids". In Marshall W. Baldwin (ed.). A History of the Crusades, Volume I: The First Hundred Years. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 135–177.

- Canard, Marius (1986). "Ḥamdānids". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. 3. pp. 126–131.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Çetinoğlu, Sait (2018). "Genocide/ Seyfo – and how resistance became a way of life". In Hannibal Travis (ed.). The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. Routledge. pp. 178–191.

- Courtois, Sébastien de (2013). "Tur Abdin : Réflexions sur l'état présent descommunautés syriaques du Sud-Est de la Turquie,mémoire, exils, retours". Cahier du Gremmamo, vol. 21 (in French): 113–150.

- Crow, James (2018). "Bezabde". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- El-Azhari, Taef (2016). Zengi and the Muslim Response to the Crusades: The politics of Jihad. Routledge.

- Elisséeff, Nur ad-Din (1986). "Ibn ʿUmar, D̲j̲azīrat". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. 3. pp. 960–961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Galante, Avram (1948). Histoire des Juifs de Turquie (in French).

- Gil, Moshe (2004). Jews in Islamic countries in the Middle Ages. Translated by David Strassler. Brill.

- Heidemann, Stefan (2002). "Zangids". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. 11. pp. 452–455.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Henning, Barbara (2018). Narratives of the History of the Ottoman-Kurdish Bedirhani Family in Imperial and Post-Imperial Contexts: Continuities and Changes. University of Bamberg Press.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (1991). "Marwanids". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. 6. pp. 626–627.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Humphreys, R. Stephen (1977). From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193-1260. State University of New York Press.

- Ignatius Jacob III (2008). History of the Monastery of Saint Matthew in Mosul. Translated by Matti Moosa. Gorgias Press.

- Jackson, Peter (2017). The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion. Yale University Press.

- James, Boris (2019). "Constructing the Realm of the Kurds (al-Mamlaka al-Akradiyya): Kurdish In-betweenness and Mamluk Ethnic Engineering (1130-1340 CE)". In Steve Tamari (ed.). Grounded Identities: Territory and Belonging in the Medieval and Early Modern Middle East and Mediterranean. Brill. pp. 17–45.

- Jongerden, Joost; Verheij, Jelle (2012). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915. Brill.

- Jwaideh, Wadie (2006). The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development. Syracuse University Press.

- Kana’an, Ruba (2013). "The Biography of a Thirteenth-century Brass Ewer from Mosul". In Sheila Blair; Jonathan M. Bloom (eds.). God Is Beautiful and Loves Beauty: The Object in Islamic Art and Culture. Yale University Press. pp. 176–193.

- Karpat, Kemal Haşim (1985). Ottoman Population, 1830-1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century. Pearson Education.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2011). "The Feeding of the five Hundred Thousand: Cities and Agriculture in Early Islamic Mesopotamia". Iraq. 73: 177–199.

- Kévorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2011). "From "Patriotism" to Mass Murder: Dr Mehmed Reşid (1873-1919)". In Ronald Grigor Suny; Fatma Müge Göçek; Norman M. Naimark (eds.). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 126–151.

- Kiraz, George A. (2011). "Giwargis II, Ignatius". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition. Gorgias Press.

- Klein, Janet (2011). The Margins of Empire: Kurdish Militias in the Ottoman Tribal Zone. Stanford University Press.

- Lightfoot, C.S. (1981). The Eastern Frontier of the Roman Empire with special reference to the reign of Constantius II.

- Mango, Andrew (2013). "Atatürk and the Kurds". In Sylvia Kedourie (ed.). Seventy-five Years of the Turkish Republic. Routledge. pp. 1–26.

- Marcus, Aliza (1994). "City in the War Zone". Middle East Report (189): 16–19.

- Mazzola, Marianna (2019). "Centralism and Local Tradition : A Reappraisal of the Sources on the Metropolis of Tagrit and Mor Matay". Le Muséon. 132 (3–4): 399–413. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Miynat, Ali (2017). Cultural and socio-economic relations between the Turkmen states and the Byzantine empire and West with a corpus of the Turkmen coins in the Barber Institute Coin Collection (PDF).

- Mutzafi, Hezy (2008). The Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Betanure (Province of Dihok). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Nicolle, David (2013). "The Zangid bridge of Ǧazīrat ibn ʿUmar (ʿAyn Dīwār/Cizre): A New Look at the carved panel of an armoured horseman". Bulletin d'études orientales. 62: 223–264.

- Özoğlu, Hakan (2001). ""Nationalism" and Kurdish Notables in the Late Ottoman–Early Republican Era". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 33 (3): 383–409.

- Özoğlu, Hakan (2004). Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries. SUNY Press.

- Palmer, Andrew (1990). Monk and Mason on the Tigris Frontier: The Early History of Tur Abdin. Cambridge University Press.

- Patton, Douglas (1991). "Badr al-Dīn Lu'lu' and the Establishment of a mamluk Government in Mosul". Studia Islamica. Brill. 74: 79–103.

- Pfeiffer, Judith (2013). "Confessional Ambiguity vs. Confessional Polarisation: Politics and the Negotiation of Religious Boundaries in the Ilkhanate". In Judith Pfeiffer (ed.). Politics, Patronage and the Transmission of Knowledge in 13th-15th Century Tabriz. Brill. pp. 129–171.

- Quataert, Donald (1994). "The Age of Reforms, 1812-1914". In Halil İnalcık; Donald Quataert (eds.). An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1914. Cambridge University Press. pp. 759–947.

- Rassi, Salam (2015). Justifying Christianity in the Islamic Middle Ages: The Apologetic Theology of ʿAbdīshōʿ bar Brīkhā (d. 1318).

- Rhétoré, Jacques (2005). Les chrétiens aux bêtes: souvenirs de la guerre sainte proclamée par les Turcs contre les chrétiens en 1915 (in French). Editions du CERF.

- Sabar, Yona (2002). A Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dictionary: Dialects of Amidya, Dihok, Nerwa and Zakho, Northwestern Iraq. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Şanlı, Süleyman (2017). "An Overview of Historical Background of Unknown Eastern Jews of Turkey". Mukaddime. 8 (1): 67–82.

- Sato, Noriko (2001). Memory and Social Identity among Syrian Orthodox Christians (PDF). Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Sinclair, T.A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III. Pindar Press. ISBN 9780907132349.

- Sinclair, Thomas (2019). Eastern Trade and the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages: Pegolotti’s Ayas-Tabriz Itinerary and its Commercial Context. Routledge.

- Snelders, Bas (2010). "The Syrian Orthodox in their Historical and Artistic Settings". Identity and Christian-Muslim Interaction: Medieval Art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area (PDF).

- Taylor, Gordon (2007). Fever and Thirst: An American Doctor Among the Tribes of Kurdistan, 1835-1844. Chicago Review Press.

- Ternon, Yves (2002). Revue d'histoire arménienne contemporaine: Mardin 1915: Anatomie pathologique d'une destruction. 4.

- Touzard, Anne-Marie (2000). "FRANCE vii. FRENCH TRAVELERS IN PERSIA, 1600-1730". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ul-Hasan, Mahmood (2005). Ibn Al-At̲h̲ir: An Arab Historian : a Critical Analysis of His Tarikh-al-kamil and Tarikh-al-atabeca. Northern Book Centre.

- Üngör, Uğur; Polatel, Mehmet (2011). Confiscation and Destruction: The Young Turk Seizure of Armenian Property. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Üngör, Uğur (2012). The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1950. Oxford University Press.

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Peeters Publishers.

- Yacoub, Joseph (2016). Year of the Sword: The Assyrian Christian Genocide, A History. Translated by James Ferguson. Oxford University Press.

- Zaken, Mordechai (2007). Jewish Subjects and Their Tribal Chieftains in Kurdistan: A Study in Survival. Brill.

- Zawanowska, Marzena (2019). "Yefet ben ʿEli on Genesis 11 and 22". In Meira Polliack; Athalya Brenner-Idan (eds.). Jewish Biblical Exegesis from Islamic Lands: The Medieval Period. SBL Press. pp. 33–61.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cizre. |