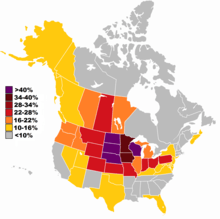

German Canadians

German Canadians (German: Deutsch-Kanadier or Deutschkanadier, pronounced [ˈdɔʏ̯tʃkaˌnaːdi̯ɐ]) are Canadian citizens or residents of ethnic German ancestry. The 2016 Canadian census put the number of Canadians of German ethnicity at over 3.3 million. Some immigrants came from what is today Germany, while larger numbers came from German settlements in Eastern Europe and Imperial Russia; others came from parts of the German Confederation, Austria-Hungary and Switzerland.

German Canadians % of population by area | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,322,405 (by ancestry, 2016 Census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Ontario, Western Canada, Atlantic Canada, Quebec | |

| Languages | |

| English • French • German | |

| Religion | |

| Protestantism • Catholicism • Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Germans, German Americans, Austrian Canadians, Swiss Canadians, Luxembourgish Canadians |

Number of German Canadians

Data from this section from Statistics Canada, 2016.[2]

| Percent | |

|---|---|

| 9.6% | |

| 1.7% | |

| 5.1% | |

| 10.7% | |

| 4.7% | |

| 1.8% | |

| 9.0% | |

| 17.7% | |

| 27.7% | |

| 17.9% | |

| 13.3% | |

| 15.9% | |

| 8.3% | |

| 2.1% |

History

When Governor Edward Cornwallis established Halifax, Nova Scotia (1749), he also settled the first German community in present-day Canada. They were known as Foreign Protestants. These were continental Protestants encouraged to come to Nova Scotia to counterbalance the large number of Catholic Acadians. This influx happened between 1750 and 1752. Family surnames, Lutheran churches and village names along the South Shore of Nova Scotia retain their German heritage, such as Lunenburg. The first German church in Canada, the Little Dutch (Deutsch) Church in Halifax, is located on land set aside for the German-speaking community in 1756. The church was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1997.[3][4]

A smaller number of Germans who had fought for prince-elector king George III during the Revolutionary War stayed in North America and mixed with the French-Canadians.[5] The American Revolution saw a small group of German-American migrants to Canada. German speakers from New York and Pennsylvania (and other areas) made up a significant percentage of United Empire Loyalists. To fight the war, Britain had hired regiments from small German states; these soldiers were known as "Hessians." About 2,200 settled in Canada once their terms of service expired or they were released from American captivity. For example, a group from the Brunswick regiment settled southwest of Montreal and south of Quebec City.[6]

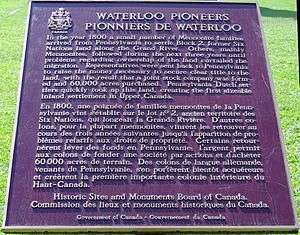

The largest group fleeing the United States were the Mennonites from the U.S., called Pennsylvania Dutch, actually Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch, (German).[7] Many of those families' ancestors had been from Southern Germany or Switzerland. Starting in the early 1800s, they moved to what is today southwest Ontario, settling around the Grand River, especially in Berlin, Ontario (now known as Kitchener) and in the northern part of what later became Waterloo County, Ontario.[8]

This same geographic area also attracted new German migrants from Europe, roughly 50,000 between the 1830 and 1860.[9][10][9] Research indicates that there was no apparent conflict between the Germans from Europe and those who came from Pennsylvania.[11]

1850 to 1900

By 1871, nearly 55 percent of the population of Waterloo County had German origins.[12] Especially in Berlin, German was the dominant language spoken. Research indicates that there was no apparent conflict between the Germans from Europe and those who came from Pennsylvania.[13]

The German Protestants developed the Lutheran Church along Canadian lines. In Waterloo County, Ontario, with large German elements that arrived after 1850, the Lutheran churches played major roles in the religious, cultural and social life of the community. After 1914 English became the preferred language for sermons and publications. Absent a seminary, the churches trained their own ministers, but there was a doctrinal schism in the 1860s. While the Anglophone Protestants promoted the Social Gospel and prohibition, the Lutherans stood apart.[14]

In Montreal, immigrants and Canadians of German-descent founded the German Society of Montreal in April 1835. The secular organization's purpose was to bring together the German community in the city, and act as a unified voice, help sick and needy members of the community and to keep alive customs and traditions.[15] The Society is still active today and celebrated its 180th anniversary in 2015.

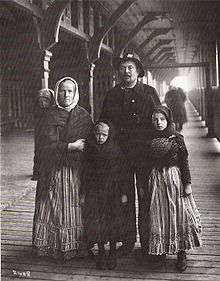

20th century

The population of the Canadian west beginning in 1896 drew further large numbers of German immigrants, mostly from Eastern Europe. Once again German-speaking Mennonites (of Dutch-Prussian ancestry) were especially prominent, being persecuted by the Tsarist regime in Russia. The farmers, used to the harsh conditions of farming in southern Imperial Russia (today's Ukraine), were some of the most successful in adapting to the Canadian prairies. This accelerated when, in the 1920s, the United States imposed quotas on Central and Eastern European immigration. Soon after Canada imposed its own limits, however, and prevented most of those trying to flee the Third Reich from moving to Canada. Many of the Mennonites settled in the Winnipeg and Steinbach, Manitoba, and the area just north of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.[16]

By the early 1900s, the northern part of Waterloo County, Ontario exhibited a strong German culture and those of German origin made up a third of the population in 1911. Lutherans were the primary religious group. There were nearly three times as many Lutherans as Mennonites at that time. The latter, who had moved here from Pennsylvania in the first half of the 1800s, primarily resided in the rural areas and small communities.[17]

Before and during World War I, there was some Anti-German sentiment in the Waterloo County area and some cultural sanctions on the community, primarily in Berlin, Ontario (now Kitchener).[7] Mennonites in the area were pacifist so they could not enlist and some who had immigrated from Germany (and were not born in Canada) found it morally difficult to fight against a country that was a significant part of their heritage.[18] It was this anti-German sentiment that precipitated the Berlin to Kitchener name change in 1916. The city was named after Lord Kitchener, famously pictured on the "Lord Kitchener Wants You" recruiting posters.

Several streets in Toronto that had previously been named for Liszt, Humboldt, Schiller, Bismarck, etc., were changed to names with strong British associations, such as Balmoral. There were anti-German riots in Victoria, BC and in Calgary, Alberta in the first years of the war.

News reports from Waterloo County, Ontario indicate that "A Lutheran minister was pulled out of his house ... he was dragged through the streets. German clubs were ransacked through the course of the war. It was just a really nasty time period.".[19] That sentiment was the primary reason for the 1916 Berlin to Kitchener name change in Waterloo County. A document in the Archives of Canada makes the following comment: "Although ludicrous to modern eyes, the whole issue of a name for Berlin highlights the effects that fear, hatred and nationalism can have upon a society in the face of war."[20]

Across Canada, internment camps opened in 1915 and 8,579 "enemy aliens" were held there until the end of the war; many were German speaking immigrants from Austria, Hungary, Germany and the Ukraine. Only 3,138 were classed as prisoners of war; the rest were civilians.[21][22]

There was also anti-German sentiment in Canada during WWII. Under the War Measures Act, some 26 POW camps opened and interned those who had been born in Germany, Italy and particularly in Japan, if they were deemed to be "enemy aliens". For Germans, this applied especially to single males who had some association with the Nazi Party of Canada. No compensation was paid to them after the war.[23] In Ontario, the largest internment centre for German Canadians was at Camp Petawawa, housing 750 who had been born in Germany and Austria.[24]

Between 1945 and 1994, some 400,000 German-speaking immigrants arrived in Canada.[25] The vast majority have been largely assimilated. Culturally and linguistically there is far less to distinguish Germans from the Anglo-French majority compared to the more visible immigrant groups.

Geography

Ethnic-bloc settlements in the Prairies

There are several German ethnic-bloc settlements in the Canadian Prairies in western Canada. Over a quarter of people in Saskatchewan are German-Canadians. German bloc settlements include the areas around Strasbourg, Bulyea, Leader, Burstall, Fox Valley, Eatonia, St. Walburg, Paradise Hill, Loon Lake, Goodsoil, Pierceland, Meadow Lake, Edenwold, Windthorst, Lemberg, Qu'appelle, Neudorf, Grayson, Langenburg, Kerrobert, Unity, Luseland, Macklin, Humboldt, Watson, Cudworth, Lampman, Midale, Tribune, Consul, Rockglen, Shaunavon and Swift Current.

Saskatchewan

In Saskatchewan the German settlers came directly from Russia, or, after 1914 from the Dakotas.[26] They came not as large groups but as part of a chain of family members, where the first immigrants would find suitable locations and send for the others. They formed compact German-speaking communities built around their Catholic or Lutheran churches, and continuing old-world customs. They were farmers who grew wheat and sugar beets.[27] Arrivals from Russia, Bukovina, and Romanian Dobruja established their villages in a 40-mile-wide tract east of Regina.[28] The Germans operated parochial schools primarily to maintain their religious faith; often they offered only an hour of German language instruction a week, but they always had extensive coverage of religion. Most German Catholic children by 1910 attended schools taught entirely in English.[29] From 1900 to 1930, German Catholics generally voted for the Liberal ticket (rather than the Provincial Rights and Conservative tickets), seeing Liberals as more willing to protect religious minorities. Occasionally they voted for Conservatives or independent candidates who offered greater support for public funding of parochial schools.[30] Nazi Germany made a systematic effort to proselytize among Saskatchewan's Germans in the 1930s. Fewer than 1% endorsed their message, but some did migrate back to Germany before anti-Nazi sentiment became overwhelming in 1939.[31]

Education

There are two German international schools in Canada:

- Alexander von Humboldt Schule Montréal

- German International School Toronto

There are also bilingual German-English K-12 schools in Winnipeg, Manitoba:

- Donwood Elementary School (K–5)

- Princess Margaret School (K–5)

- Chief Peguis Junior High (6–8)

- River East Collegiate (9–12)

- Westgate Mennonite Collegiate (6-12)

See also

- Germans

- German Americans

- Hessian (soldiers)

- German inventors and discoverers

- German Mills, Ontario

- German Canadian Club Hansa

- Waterloo County, Ontario

References

Notes

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables - Ethnic Origin, both sexes, age (total), Canada, 2016 Census – 25% Sample data". www12.statcan.gc.ca.

- "2016 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations | Ethnic Origin (247), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census - 20% Sample Data". Statistics Canada. 2020-01-11. Retrieved 2020-01-11.

- "HistoricPlaces.ca - HistoricPlaces.ca". Historicplaces.ca. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Little Dutch (Deutsch) Church National Historic Site of Canada. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- Wilhelmy: Les Mercenaires allemands au Québec, 1776-1783

- Lehmann (1986) p 371

- "HistoricPlaces.ca - HistoricPlaces.ca". Historicplaces.ca. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- "Waterloo Township". Waterloo Region Museum Research. Region of Waterloo. 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- "German Canadians". The Canadian Encyclopedia. The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Lehmann (1986) passim

- "Religion in Waterloo North (Pre 1911)". Waterloo Region. Waterloo Region. 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- "Full text of "Waterloo County to 1972 : an annotated bibliography of regional history"". archive.org. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- "Religion in Waterloo North (Pre 1911)". Waterloo Region. Waterloo Region. 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- Wilfrid H. Heick, "Becoming an Indigenous Church: The Lutheran Church in Waterloo County, Ontario," Ontario History, Dec 1964, Vol. 56 Issue 4, pp 249–260

- Gürttler, Karin R. (1985). Geschichte der Deutschen Gesellschaft zu Montreal (1835-1985). Montreal, QC: German Society of Montreal. p. 108. ISBN 2-9800421-0-2.

- Lehmann (1986) pp 186–94, 198–204

- "Waterloo Region Pre-1914". Waterloo Region WWI. University of Waterloo. 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- D'Amato, Louisa (28 June 2014). "First World War ripped away Canada's 'age of innocence'". Kitchener Post, Waterloo Region Record. Kitchener. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- "Kitchener mayor notes 100th year of name change". Cbc.ca. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- "ARCHIVED - Did You Know That… - ARCHIVED - Canada and the First World War - Library and Archives Canada". Collectionscamnada.gc.ca. 30 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Anti-German Sentiment". Canadian War Museum. Government of Canada. 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- Tahirali, Jesse (3 August 2014). "First World War internment camps a dark chapter in Canadian history". CTV News. Bell Media. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- "INTERNMENT IN CANADA: WW1 VS WW2". ALL ABOUT CANADIAN HISTORY. ALL ABOUT CANADIAN HISTORY. 23 February 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- MacKinnon, Dianne (16 August 2011). "Canadian Internment Camps". Renfrew County Museums. Renfrew County Museums. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- "German Canadians". Canadian Encyclopedia. Canadian Encyclopedia. 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- Heinz Lehmann and Gerhard P. Bassler, The German Canadians, 1750–1937: immigration, settlement & culture (1986)

- Jessica Clark and Thomas D. Isern, "Germans from Russia in Saskatchewan: An Oral History," American Review of Canadian Studies, Spring 2010, Vol. 40 Issue 1, pp 71–85

- Adam Giesinger, "The Germans from Russia Who Pioneered in Saskatchewan," Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Summer 1984, Vol. 7 Issue 2, pp 1–14

- Clinton O. White, "Pre-World War I Saskatchewan German Catholic thought concerning the perpetuation of their language and religion," Canadian Ethnic Studies, 1994, Vol. 26 Issue 2, pp 15–30

- Clinton O. White, "The Politics of Elementary Schools in a German-American Roman Catholic Settlement in Canada's Province of Saskatchewan, 1903–1925," Great Plains Research, Sept 1997, Vol. 7 Issue 2, pp 251–272

- Jonathan F. Wagner, "The Deutscher Bund Canada in Saskatchewan," Saskatchewan History, May 1978, Vol. 31 Issue 2, pp 41–50

Further reading

- Antor, Heinz (2003) Refractions of Germany in Canadian literature and culture Walter de Gruyter

- Becker, Anthony. "The Germans in Western Canada, A Vanishing People." Bulletin of the Canadian Catholic Historical Association (1975). online

- Foster, Lois, and Anne Seitz. "Official attitudes to Germans during World War II: some Australian and Canadian comparisons." Ethnic and Racial Studies 14.4 (1991): 474–492.

- Freund, Alexander. "Troubling memories in Nation-Building: World War II memories and Germans' inter-ethnic encounters in Canada after 1945." Social History 39.77 (2006): 129+. online

- Grams, Grant W.: German Emigration to Canada and the Support of its Deutschtum during the Weimar Republic - the Role of the Deutsches Ausland Institut, Verein für das Deutschtum im Ausland and German-Canadian Organisations (Peter Lang Publishers, Frankfurt am Main, 2001.

- Grams, Grant W.: "Der Volksverein deutsch-canadischer Katholiken, the rise and fall of a German-Catholic Cultural and Immigration Society, 1909-1952", The Catholic Historical Review, 2013.

- Grams, Grant W.: "The Deportation of German Nationals from Canada, 1919 to 1939", Journal of International Migration and Integration, 2010.

- Grams, Grant W.: "Immigration and Return Migration of German Nationals, Saskatchewan 1919 to 1939", Prairie Forum, 2008.

- Grams, Grant W.: "Karl Respa and German Espionage in Canada during World War One", Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 2005.

- Grams, Grant W.: "Sankt Raphael’s Verein and German-Catholic Emigration to Canada between 1919 and 1939", The Catholic Historical Review, 2005.

- Gürttler, Karin R. "Geschichte der Deutschen Gesellschaft zu Montreal (1835-1985)". (1985) Montreal, QC: German Society of Montreal. 108 p. ISBN 2-9800421-0-2.

- Lehmann, Heinz. German-Canadians 1750–1937 (1986)

- Keyserlingk, Robert H. "The Canadian Government's Attitude Towards Germans and German Canadians in World War Two." Canadian ethnic studies= Études ethniques au Canada 16.1 (1984): 16+.

- McLaughlin, K. M. The Germans in Canada (Canadian Historical Association, 1985).

- Magocsi, Paul, ed. Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples (1999) extensive coverage

- Sauer, Angelika E. "The unbounded German nation: Dr. Otto Hahn and German emigration to Canada in the 1870s and 1880s." Canadian Ethnic Studies 39.1-2 (2007): 129–144.

- Wagner, Jonathan. A History of Migration from Germany to Canada 1850–1939 (UBC Press, 2006)

- Waters, Tony. "Towards a theory of ethnic identity and migration: the formation of ethnic enclaves by migrant Germans in Russia and North America." International Migration Review 29.2 (1995): 515–544.

- (in French) Meune, Manuel. Les Allemands du Québec: Parcours et discours d'une communauté méconnue. Montréal: Méridien, 2003. ISBN 2-89415293-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canadians of German descent. |

- German Clubs, Communities and Businesses in Canada and USA

- University of Alberta's History of Germans in Alberta

- Multicultural Canada website including German books and periodicals and digitized issues of the Berliner Journal, 1880–1916

- History of Ours: the German People A history of Germans in Brantford, Ontario.

- German Canadian Club "Hansa Haus" in Mississauga, Ontario German-Canadian Cultural Centre in the GTA

- German Canadian Association of Nova Scotia Nonprofit organization in Nova Scotia that promotes German Canadian heritage and cultures

- German Canadian Congress