History of the Jews in Chicago

At the end of the 20th century there were a total of 270,000 Jews in the Chicago area, with 30% in the city limits. [1] In 1995 there were 154,000 Jews in the suburbs of Chicago. Of them, over 80% of the Jews in the suburbs of Chicago live in the northern and northwestern suburbs.[2] In 1995, the largest Jewish community in the City of Chicago was in West Rogers Park. By 1995 the Jewish population within the City of Chicago had been declining, and it tended to be older and more well educated than the Chicago average.[3] Jews in Chicago came from many national origins including those in Europe and Middle East, with Eastern Europe and Germany being the most common.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Ethnic groups in Chicago |

|---|

History

Jews arrived in Chicago immediately after its 1833 incorporation.[1] The Ashkenazi were the first Jewish group settling in Chicago. In the late 1830s and early 1840s a group of German Jews came to Chicago. Most of them were from Bavaria.[4] On Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) 1845 the first Jewish religious service in Chicago was held.[5] Many Jews peddled items on streets. They later opened small stores, which were the basis of several companies.[1] In this time the Jewish community was constantly growing, and when the American Civil War began, the community itself recruited a company of 100 Jews to join the 82nd Regiment of Illinois Volunteers.[6]

Originally the Jews lived in the Downtown area, but this changed after the Great Chicago Fire occurred in 1871. Many moved to lakeside communities such as Hyde Park, Kenwood, and South Shore.[1]

Immigration from Eastern Europe

The first wave of Eastern European Jewish immigration, with many coming from shtetls in Poland and Russia, started in the 1870s. The Eastern European and German Jewish communities remained separate until the mid-20th century due to different cultural practices and religious practices. The Eastern European Jews originally moved to the Maxwell Street area in the Near Westside, which at the time was one of the poorest areas of Chicago. Many of the Jews worked as artisans, workers in factories, peddlers, and petty merchants. The factory workers were primarily in the clothing sector. In that community an outdoor market and 40 synagogues opened. Irving Cutler wrote that the Jews in the Maxwell Street area "created a community with some resemblance to the Old World shtetl with its numerous Jewish institutions".[1]

By 1910 Eastern European Jews were moving to new communities due to educational opportunities and income from entrepreneurial activities. The largest group went to North Lawndale. Other neighborhoods receiving Eastern European Jews included northwestern communities such as Albany Park, Humboldt Park, and Logan Square. Northern communities along the lake receiving Eastern European Jews included Lake View, Rogers Park, and Uptown. A group of Eastern European Jews moved into the German Jewish community on the South Side of Chicago.[1]

Suburbanization

In the post-World War I era a group of Jews, mostly consisting of descendants of immigrants from Germany, settled in the North Shore of Chicago, including Glencoe and Highland Park.[7]

There were 275,000 Jews in Chicago by 1930, making it the third largest Jewish population after New York City and Warsaw.[8] In that year, 80% of Chicago's Jews were of Eastern European heritage.[1] The Chicago Jews were 8% of the city's population.[8]

In 1950, 5% of the Chicago area Jews lived in suburbs. As part of the first wave of suburbanization, in the early 1950s Jews began moving to Lincolnwood and Skokie because they had relatively inexpensive vacant land and because of the 1951 opening of the Edens Expressway.[7] Homebuilders, often Jewish homebuilders who advertised to Jewish communities, constructed single family houses in Skokie and Lincolnwood. Ultimately most northern suburbs were settled by Jews except those which Jews were barred from: Kenilworth and Lake Forest had prevented Jews from moving in.[9] The number of Jews in the suburbs increased to 40% by the early 1960s.[7]

Present Day

In 1982 there were about 248,000 Jews in the Chicago metropolitan area, making up about 4% of the population. Due to a loss of Jewish identity, loss of immigration, low birthrate, some youth being alienated from the Jewish community, and intermarriage leading to assimilation, the Jewish population had declined. Households became smaller and overall the population had aged. Most suburban Jews no longer spoke Yiddish.[10]

Synagogues and Jewish Organizations including The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute are working to show how Judaism is relevant to the present generation. [11] [12] [13] [14][15]

Geography

In 1995, of the 248,000 Jews living in Chicago area, over 80% live north of Lawrence Avenue (4800 north) and over 62% of the entire population of Chicago area Jews lives in suburban communities.[7] In 1995, Glencoe, Highland Park, Lincolnwood, and Skokie had estimates of being almost 50% Jewish. In that year, Buffalo Grove and Deerfield had estimates of being over 25% Jewish. In the same year, Evanston, Glenview, Morton Grove, Niles, Northbrook, Wilmette, and Winnetka had estimates of being 10-25% Jewish. In 1995, due to relatively inexpensive housing and vacant land, young Jewish families were moving into suburbs further away from the Chicago Loop in the northwest side. the suburban Jewish population "continues to be dispersed over a widening geographic area" which hampers the ability to supply certain Jewish-oriented services.[9] Cutler wrote that inter-suburban movement was occurring among Jews.[9]

In 1995 Irving Cutler wrote that the Jewish populations of Deerfield and Northbrook had recent growth, and he also stated that the Jewish community of Buffalo Grove was "large and growing".[9] The Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago estimated in 1975 that of the almost 70,000 residents in Skokie, Jewish people made up 40,000 of them. In 1995 Irving Cutler wrote that there had been a recent decline of Jews in Skokie due to children of post-World War II households growing up and moving out, and that there had especially been inter-suburban movement of Jews from Skokie.[9]

In 1995, 85,000 Jews lived in the City of Chicago, with 80,000 of them living in contiguous Jewish communities within the city and in a series of northside lakefront communities. The contiguous Jewish communities included West Rogers Park/West Ridge and the lakefront area ranges from the Chicago Loop to Rogers Park. In that year, the Hyde Park-Kenwood area has a population of Jews.[7] In 1995 Cutler wrote that in the city the Jewish population was being concentrated in fewer and fewer neighborhoods.[9]

Irving Cutler, author of the article "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb," stated that Jews living in southern and western suburbs of Chicago and in Northwest Indiana "often feel removed from the mainstream of Chicago Jewry" since they do not have Jewish services and have smaller numbers than the main group of Jews to the north.[7] In 1995, the Oak Park-River Forest-Westchester area to the west had a Jewish community. In the same year, the Glenwood-Homewood-Flossmoor-Olympia Fields-Park Forest area to the south had another Jewish community. In 1995, some Northwest Indiana cities such as East Chicago, Hammond, and Michigan City had Jewish populations in 1996; Cutler stated that the Northwest Indiana Jewish populations were "small and often declining".[7]

Institutions

The United Hebrew Relief Association (UHRA) was founded in 1859. 15 Jewish organizations, including some B'nai B'rith lodges and some women's organizations, together founded the UHRA.[1]

The earlier German Jewish community founded many institutions to deliver services to its people. These include the following: The Michael Reese Hospital was founded in 1882; The Drexel Home, a home for elderly Jews, was founded in 1891 at 62nd St. and Drexel Ave; The Standard Club, a civic and social club, located at 320 S. Plymouth Ct., was opened in 1869. The Eastern European Jews founded the Jewish Training School in 1890, the Chicago Maternity Center in 1895, and the Chicago Hebrew Institute in 1903.[1]

Over time, even more institutions for care of the young and old were founded. Here is a timeline:

1899-Chicago Home for Jewish Orphans (Woodlawn Hall)

1900-BMZ-Beth Moshev Z’elohim (Orthodox Jewish Home for the Aged), located at 1648 S. Albany Ave. is founded an opens its doors to 15 residents in 1903.

1913-Federated Orthodox Charities (later merged with Associated Jewish Charities, which ultimately became Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago, in 1950.

1914-Rose Eisenberg Memorial Home (Park View Home) of the Daughters of Zion and Daughters of Jacob originally started out as a day and night nursery servicing the needs of immigrant families who worked and required day and night care for their children. The nursery moved to a new building in 1928 and the children's care was discontinued in 1950.

1951-Park View Home, the former Eisenberg Home, affiliated with JUF and converted the building into an elderly care facility which ultimately became the Park View Home. With a $300,000 gift from the Eisenberg family, the facility adopted the name Park View Home - Rose Eisenberg Memorial - of the Daughters of Zion and Daughters of Jacob.

1953-First 10 residents, both male and female - were admitted to the Home. Its capacity was 136 residents

1966-The Board of Directors of the Jewish Federation met to consider emerging problems cited in an internal research report on Services to the Aged. At this time, JF owned Drexel Home, BMZ, and Park View Home and the need for change in these and other programs were becoming apparent.

1968-A study was conducted and the Gerontological Council of the JF was established.

1971-The Council for Jewish Elderly, later renamed to become CJE SeniorLife, was founded by the Jewish Federation to provide services to elderly Jews in their residences and provide housing.

The Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center is located in Skokie.

Education

In 1995 Jews in Chicago attend universities at twice the rate of the overall population, and this contributes to the overall higher than average incomes.[10]

Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership is located in Chicago.

Universities include:

Primary and secondary schools:

- Akiba-Schechter Jewish Day School

- Bernard Zell Anshe Emet Day School

- Chicago Jewish Day School

- Fasman Yeshiva High School

- Ida Crown Jewish Academy

- Rochelle Zell Jewish High School (former Chicagoland Jewish High School)

- Telshe Yeshiva

There is also a museum, Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center.

Religion

In 1995, there were about 24 Jewish congregations in Lincolnwood and Skokie. Most of them are Conservative or Orthodox-Traditional synagogues. One rabbinical college is in Skokie. In 1995 the North Shore suburbs further from the Chicago Loop have mostly Reform congregations. In the same year, the following further-out suburbs with newer Jewish settlement have synagogues: Buffalo Grove, Des Plaines, Hoffman Estates, Vernon Hills, and Wheeling. In that year, Six synagogues are in the area around Buffalo Grove. In 1995 West Rogers Park in the City of Chicago has many elderly Jews and Jews born abroad, so it has larger groups of Orthodox synagogues.[9]

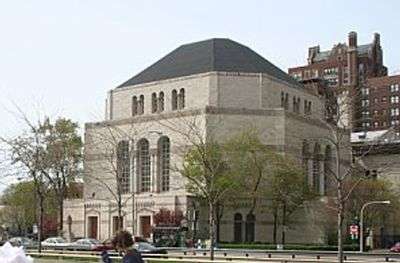

The first synagogue in Chicago was the Kehilath Anshe Mayriv (KAM), located at the intersection of Lake and Wells. German Jewish immigrants founded it in 1847. Kehilath B'nai Sholom, the second congregation, was founded by 20 Polish Jews in 1852. They were dissatisfied with KAM. Kehilath B'nail Shalom was more Orthodox than KAM. In 1861 the Sinai Reform Congregation formed, using a church near the intersection of LaSalle and Monroe as its place of worship. The founders were a group of former KAM members with Rabbi Bernhard Felsenthal as the leader.[1]

In 1920 a synagogue opened in Glencoe. This synagogue, the first synagogue in the North Shore, was a branch of the Sinai Congregation (Reform) synagogue of the South Side but it became the North Shore Congregation Israel, an independent synagogue. In 1952 the first synagogue serving Lincolnwood and Skokie, the Niles Township Jewish Congregation, opened.[7]

Notable Jews of metropolitan Chicago

- Saul Alinsky

- Morey Amsterdam

- Bob Balaban

- Saul Bellow

- Mike Bloomfield

- Neil Bluhm

- Leonard Chess

- Henry Crown

- Larry Ellison

- Ari Emanuel

- Ezekiel Emanuel

- Rahm Emanuel, Mayor of Chicago

- Ephraim Epstein

- Milton S. Florsheim

- Arthur Goldberg

- Maurice Goldblatt

- Benny Goodman

- Albert Grossman

- Henry Horner, Governor of Illinois

- Peter Jacobson

- Edward H. Levi

- Steven Levitan

- David Mamet

- Edward Morris

- Ira Nelson Morris

- Nelson Morris

- Arnie Morton[16]

- William S. Paley

- Mandy Patinkin

- Jeremy Piven

- Sol Polk

- Abram Nicholas Pritzker

- Daniel Pritzker

- Donald Pritzker

- Gigi Pritzker

- Harry Nicholas Pritzker

- Jack Nicholas Pritzker

- Jay Pritzker

- John Pritzker

- Nicholas J. Pritzker

- Penny Pritzker

- Rhoda Pritzker

- Robert Pritzker

- Thomas Pritzker

- Julius Rosenwald

- Lessing J. Rosenwald

- William Rosenwald

- Abram M. Rothschild

- Jack Ruby

- Ernest Samuels

- Edwin Silverman

- Gene Siskel

- Joseph Spiegel

- Marcus M. Spiegel

- Jill Stein

- Studs Terkel

- Mel Torme

- Sam Zell

- Warren Zevon

References

- Cutler, Irving. "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb" (Chapter 5). In: Holli, Melvin G. and Peter d'Alroy Jones. Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995. Start page 122. ISBN 0802870538, 9780802870537.

Notes

- Cutler, Irving. "Jews." Encyclopedia of Chicago History. Retrieved on March 4, 2014.

- Cutler, "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb," Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait, p. 165-166.

- Cutler, "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb," Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait, p. 165.

- Cutler, "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb," Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait, p. 123.

- Cutler, "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb," Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait, p. 123-124.

- "The Jewish Community of Chicago". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

- Cutler, "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb," Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait, p. 166.

- Cutler, "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb," Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait, p. 122.

- Cutler, "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb," Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait, p. 168

- Cutler, "The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb," Ethnic Chicago: A Multicultural Portrait, p. 169.

- Wilkinson, Phaedra (October 21, 2014). "From the community: Exciting Class on Jewish Positive Psychology to be Presented in Northbrook". Chicago: Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

The Jewish Learning Institute's (JLI) Newest Class Looks at Positive Psychology through the 3,000-year-old lens of Jewish thought. Northbrook, IL - When Israeli-born psychologist Tal Ben-Shahar began teaching a class called Positive Psychology at Harvard in 2006, a record 855 undergraduate students signed up for his class. Droves of students at the academically-intense university came to learn, as the course description puts it, about "psychological aspects of a fulfilling and flourishing life."

- "Economic crisis from a Jewish perspective". The Naperville Sun (Chicago Tribune). The Sun - Naperville (IL) via HighBeam. January 27, 2012. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015.

Money Matters has been developed by the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute and will be taught in 300 locations throughout the world

- "Torah and Torts". Chicago Jewish News (original publisher). Archived article at JLI Central. February 20, 2009.

At a time when every other news story seems to involve a matter of ethics, Rabbi Meir Hecht is teaching his adult students - many of them lawyers - how to understand complicated ethical issues with help from the Torah. Hecht is the coordinator for the Jewish Learning Institute, which is currently offering a class called "You Be The Judge," with Thursday morning and evening classes at Lubavitch Chabad of Skokie. (Childcare is available during the morning classes.) Lawyers can receive Continuing Legal Education and ethics credits through the class, but its lessons are for anyone - Jewish or non-Jewish-who is interested in pursuing the intersection between law and ethics, Hecht said in a recent phone conversation.

- Independent Press (October 26, 2014). "Happiness and Positive living series starts Nov. 5 at Chabad of SE Morris County in Madison". New Jersey On-Line. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

How Happiness Thinks was created by the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute- an internationally acclaimed adult education program running on over 350 cities worldwide, which boast over 75,000 students. This particular course builds on the latest observations and discoveries in the field of positive psychology. How Happiness Thinks offers participants the chance to earn up to 15 continuing education credits from the American Psychological Association (APA), American Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and the National Board of Certified Counselors (NBCC).

- Open Source Contributor. "Promoting Jewish Medical Awareness In Northbrook". Chicago Tribune. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "HPHS Jewish 'Fame and Fortune' Alumni" (PDF). Chicago Jewish Historical Society. Fall 2007.

Further reading

- Bregstone, Philip P. Chicago and Its Jews: A Cultural History. Philip P. Bregstone, 1933.

- Brinkmann, Tobias. "Sundays at Sinai" A Jewish Congregation in Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012. ISBN 9780226074542.

- Chicago Jewish History. Chicago: Chicago Jewish Historical Society, 1989—current.

- Chicago Sinai Congregation: A Pictorial History. Chicago: Chicago Sinai Congregation, 1986.

- Cutler, Irving. The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb. University of Illinois Press, 1996. ISBN 0252021851, 9780252021855.

- Cutler, Irving. Chicago's Jewish West Side. Arcadia Publishing, 2009. ISBN 0738560154, 9780738560151.

- Cutler, Irving. Jewish Chicago: A Pictorial History. Arcadia Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0738501301, 9780738501307.

- Meites, Hyman Louis (editor). History of the Jews of Chicago. Chicago Jewish Historical Society, 1924. ISBN 0922984042, 9780922984046. 1990 reprint available.

- Rosen, Rhoda (editor). The Shaping of a Community: The Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago. Chicago: Spertus Press, 1999.

- Roth, Walter. Looking Backward: True Stories from Chicago's Jewish Past. Academy Chicago Publishers, Limited, 2005. ISBN 0897335406, 9780897335409.

- The Sentinel's History of Chicago Jewry, 1911–1986. Chicago: Sentinel Pub. Co., 1986.

- Synagogues of Chicago. Chicago: Chicago Jewish Historical Society, 1991.