Pike and shot

Pike and shot is a historical infantry combat formation that evolved during the Italian Wars before the late seventeenth century evolution of the bayonet. The infantry formations of the period were a mix of pike and early firearms ("shot"), either arquebusiers or musketeers. The tactic was developed in the late 15th and early 16th centuries by the armies of the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Spain, and further innovated by Dutch and Swedish forces in the 17th century.

Origin

By the end of the fifteenth century, those late-medieval troop types that had proven most successful in the Hundred Years' War and Burgundian Wars dominated European warfare, especially the heavily armoured gendarme (a professional version of the medieval knight), the Swiss and Landsknecht mercenary pikeman, and the emerging artillery corps of heavy cannons, which were rapidly improving in technological sophistication. The French army of the Valois kings was particularly formidable due to its combination of all of these elements. The French dominance of warfare at this time presented a daunting challenge to those states which were opposed to Valois ambitions, particularly in Italy.

Emperor Maximilian I (1493-1519) opposed the French armies with the establishment of the Landsknechte units. Many of their tactics were adapted from the Swiss mercenaries, but the use of firearms was added. The firearms, in conjunction with the pike formations, gave the Imperials a tactical edge over the French. Those pike and shot regiments were recruited in Germany, Austria, and Tyrol.

A simulaneous development took place in the Spanish forces. In 1495 at the Battle of Seminara, the hitherto-successful Spanish army was trounced while opposing the French invasion of Naples by an army composed of armoured gendarme cavalry and Swiss mercenary infantry.

The chastened Spanish undertook a thorough reorganization of their army and tactics under the great captain Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba. Realizing that he could not match the sheer offensive power of the French gendarmes and Swiss pikes, Fernández de Córdoba decided to integrate the shooting power of firearms, an emerging technology at the time, with the defensive strength of the pike, and to employ them in a mutually-supporting formation, preferably in a strong defensive position.

At first, this mixed infantry formation was referred to as a colunella ("colonelcy"), and was commanded by a colonel. It interspersed formations of men in close order armed with the pike and looser formations armed with the firearm, initially the arquebus. The arquebusiers could shoot down their foes, and could then run to the nearby pikemen for shelter if enemy cavalry or pikes drew near. This was especially necessary because the firearms of the early sixteenth century were inaccurate, took a very long time to load and only had a short range, meaning the shooters were often only able to get off a few shots before the enemy was upon them.

This new tactic resulted in triumph for the Spanish and Fernández de Córdoba's colunellas at the Battle of Cerignola, one of the great victories of the Italian Wars, in which the heavily outnumbered Spanish pike-and-shot forces, in a strong defensive position, crushed the attacking gendarmes and Swiss mercenaries of the French army.

The sixteenth century

Spanish and Imperial developments

The armies of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, developed significantly the "Pike and shot" tactic. The front line of Charles' German Landsknechte consisted of doppelsöldner, renowned for their use of arquebus and zweihänder during the Italian wars. The Spanish colunellas continued to show valuable flexibility as the Great Italian Wars progressed, and the Spanish string of battlefield successes continued. The colunellas were eventually replaced by the tercios in the 1530s by order of Charles. The tercios were originally made up of one third pikemen, one third arquebusiers and one third swordsmen. Tercios were administrative organizations and were in charge of up to 3000 soldiers. These were divided into ten companies that were deployed in battle. These companies were further subdivided into small units that could be deployed individually or brought together to form great battle formations that were sometimes called Spanish squares.

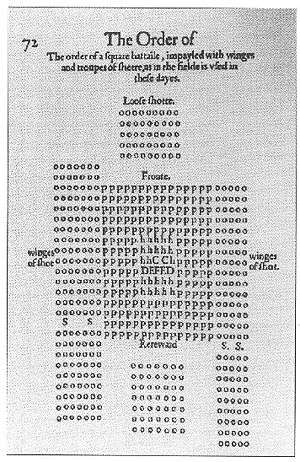

As these squares matured in usage during the sixteenth century, they generally took on the appearance of a "bastioned square" – that is, a large square with smaller square "bastions" at each corner. The large square in the center was made up of the pikemen, 56 files across and 22 ranks deep. The outer edges of the central pike square were lined with a thin rank of arquebusiers totaling 250 men. At each corner of this great pike square were the smaller squares of arquebusiers, called mangas (sleeves), each 240 men strong. Finally, two groups in open order, each of 90 men and armed with the longer musket, were placed in front of, and to the sides of, the arquebusiers.

Normal attrition of combat units (including sickness and desertion) and the sheer lack of men usually led to the tercios being far smaller in practice than the numbers above suggest but the roughly 1:1 ratio of pikemen to shooters was generally maintained. The tercios for all armies were usually of 1,000 to 2,000 men, although even these numbers could be reduced by the conditions already mentioned. Tercio type formations were also used by other powers, chiefly in the Germanic areas of the Holy Roman Empire.

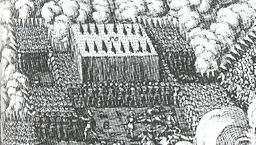

To modern eyes the tercio square seems cumbersome and wasteful of men, many of the soldiers being positioned so that they could not bring their weapons to bear against the enemy. However, in a time when firearms were short-ranged and slow to load, it had its benefits. It offered great protection against cavalry – still the dominant fast-attack arm on the battlefield – and was extremely sturdy and difficult to defeat. It was very hard to isolate or outflank and destroy a tercio by maneuver due to its great depth and distribution of firepower to all sides (as opposed to the maximization of combat power in the frontal arc as adopted by later formations). The individual units of pikemen and musketeers were not fixed and were re-ordered during battle to defend a wing or to bring greater fire power or pikes to bear in a certain direction. Finally, its depth meant that it could run over shallower formations in a close assault – that is, should the slow moving tercio manage to strike the enemy line.

Armies using the tercio generally intended to field them in brigades of at least three, with one tercio in the front and two behind, the rearward formations echeloned off on either side so that all three resembled a stepped pyramid. The word tercio means "a third" (that is, one third of the whole brigade). This entire formation would be flanked by cavalry. The musketeers, and those arquebusiers whose shooting was not blocked by friendly forces, were supposed to keep up a continuous fire by rotation. This led to a fairly slow rate of advance, estimated by modern writers at roughly 60 meters a minute. Movement of such seemingly unwieldy groups of soldiers was difficult but well trained and experienced tercios were able to move and manoeuvre with surprising facility and to great advantage over less experienced opponents. They would be co-ordinated with each other in a way that often caught attacking infantry or cavalry with fire coming from different directions from two or more of these strong infantry squares.

The French failure to keep pace

The great rivals of the Spanish/Habsburg Empire, the Kings of France, had access to a smaller and poorly organized force of pike and shot. The French military establishment showed considerably less interest in shot as a native troop type than did the Spanish until the end of the sixteenth century, and continued to prefer close combat arms, particularly heavy cavalry, as the decisive force in their armies until the French Wars of Religion; this despite the desire of King Francis I to establish his own pike and shot contingents after the Battle of Pavia, in which he was defeated and captured. Francis had declared the establishment of the French "Legions" in the 1530s, large infantry formations of 6,000 men which were roughly composed of 60% pikemen, 30% arquebusiers and 10% halberdiers. These legions were raised regionally, one in each of Normandy, Languedoc, Champagne and Picardy. Detachments of around 1,000 men could be sent off to separate duty, but in practice the Legions were initially little more than an ill-disciplined rabble and a failure as a battlefield force, and as such were soon relegated to garrison duty until they matured in the seventeenth century.

In practice, pike and shot formations that the French used on the sixteenth-century battlefield were often of an ad hoc nature, the large blocks of Swiss mercenary, Landsknecht, or, to a lesser extent, French pikemen being supported at times by bands of mercenary adventurer shot, largely Gascons and Italians. (The Swiss and Landsknechts also had their own small contingents of arquebusiers, usually comprising not more than 10-20% of their total force.) The French were also late to adopt the musket, the first reference to their use being at the end of the 1560s—twenty years after its use by the Spanish, Germans and Italians.

This was essentially the condition of the French Royal infantry throughout the French Wars of Religion that occupied most of the latter sixteenth century, and when their Huguenot foes had to improvise a native infantry force, it was largely made up of arquebusiers with few if any pikes (other than the large blocks of Landsknechts they sometimes hired), rendering formal pike and shot tactics impossible.

In the one great battle fought in the sixteenth century between the French and their Imperial rivals after the Spanish and Imperial adoption of the tercio, the Battle of Ceresole, the Imperial pike and shot formations shot down attacking French gendarmes, defending themselves with the pike when surviving heavy cavalry got close. Although the battle was ultimately lost by the Spanish and Imperial forces, it demonstrated the self-sufficiency of the mixed pike and shot formations, something sorely lacking in the French armies of the day.

Dutch reforms

Foremost amongst the enemies of the Spanish Habsburg empire in the late 16th century were the Seven Provinces of the Netherlands (often retroactively known as the "Dutch"), who fought a long war of independence from Spanish control starting in 1568. After soldiering on for years with a polyglot army of foreign-supplied troops and mercenaries, the Dutch took steps to reform their armies starting in 1590 under their captain-general, Maurice of Nassau, who had read ancient military treatises extensively.

In addition to standardizing drill, weapon caliber, pike length, and so on, Maurice turned to his readings in classical military doctrine to establish smaller, more flexible combat formations than the ponderous regiments and tercios which then presided over open battle. Each Dutch battalion was to be 550 men strong, similar to the size of the ancient Roman legionary 480-man cohort described by Vegetius. Although inspired by the Romans, Maurice's soldiers carried the weapons of their day—250 were pikemen and the remaining 300 were arquebusiers and musketeers, 60 of the shot serving as a skirmish screen in front of the battalion, the rest forming up in two equal bodies, one on either side of the pikemen. Two or more of these battalions were to form the regiment, which was thus theoretically 1,100 men or stronger, but unlike the tercio, the regiment had the battalions as fully functional sub-units, each of mixed pike and shot which could, and generally did, operate independently, or could support each other closely.

These battalions were fielded much less deep than the infantry squares of the Spanish, the pikemen being generally described as five to ten ranks deep, the shot eight to twelve ranks. In this way, fewer musketeers were left inactive in the rear of the formation, as was the case with tercios which deployed in a bastioned-square.

Maurice called for a deployment of his battalions in three offset lines, each line giving the one in front of it close support by means of a checkerboard formation, another similarity to Roman military systems, in this case the Legion's Quincunx deployment.

In the end, Maurice's armies depended primarily on defensive siege warfare to wear down the Spanish attempting to wrest control of the heavily fortified towns of the Seven Provinces, rather than risking the loss of all through open battle. On the rare occasion that open battle occurred, this reformed army, as many reformed armies have done in the past, behaved variably, running from the Spanish tercios one day, fighting those same tercios only a few days later, at the Battle of Nieuwpoort, and crushing them. Maurice's reforms are more famous for the effect they had on others—taken up and perfected, and would be put to the test on the battlefields of the seventeenth century.

Seventeenth century: Swedish innovations

After bad experiences with the classic tercios formations in Poland, Gustav II Adolf decided to reorganize his battlefield formations, initially adopting the "Dutch formations", but then adding a number of innovations of his own.

He started by re-arranging the formations to be thinner, typically only four to six ranks deep, spreading them out horizontally into rectangles instead of squares. This further maximized the number of musketeers near the front of the formation. Additionally he introduced the practice of volley fire, where all of the gunners in the ranks would fire at the same time. This was intended to bring down as many members of the opposing force's front line as possible, causing ranks moving up behind them to trip and fall as they were forced forward by the ranks further back. Finally, he embedded four small "infantry guns" into each battalion, allowing them to move about independently and not suffer from a lack of cannon fire if they became detached.

Gustav also placed detached musketeers in small units among the cavalry. In traditional deployments the infantry would be deployed in the middle with cavalry on both sides, protecting the flanks. Battles would often open with the cavalry attacking their counterparts in an effort to drive them off, thereby opening the infantry to a cavalry charge from the side. An attempt to do this against his new formations would be met with volley fire, perhaps not dangerous on its own, but giving the Swedish cavalry a real advantage before the two forces met. Under normal conditions detached musketeers without pikemen would be easy targets for the enemy cavalry, but if they did close to sabre range, the Swedish cavalry would be a more immediate concern.

The effect of these changes was profound. Gustav had been largely ignored by most of Europe after his mixed results in Poland, and when he arrived in Germany in 1630 he was not immediately challenged. He managed to build up a force of 24,000 regulars and was joined by a force of 18,000 Saxons of questionable quality under von Arnim. Battle was first joined in major form when Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly turned his undefeated 31,000 man veteran army to do battle, meeting Gustav at the Battle of Breitenfeld in 1631. Battle opened in traditional fashion, with Tilly's cavalry moving forward to attack the flanks. This drove off the Saxons on the one flank, but on the other Gustav's new combined cavalry/musket force drove off any attempt to charge. With one flank now open Tilly nevertheless had a major positional advantage, but Gustav's smaller and lighter units were able to easily re-align to face the formerly open flank, their light guns cutting into their ranks while the heavier guns on both sides continued to exchange fire elsewhere. Tilly was soon driven from the field, his forces in disarray.

Follow-up battles had similar outcomes, and Tilly was eventually mortally wounded during one of these. By the end of 1632 Gustav controlled much of Germany. His successes were short-lived however, as the opposing Imperial forces quickly adopted similar tactics. From this point on pike and shot formations gradually spread out into ever-wider rectangles in order to maximize firepower of the muskets. Formations became more flexible, with more firepower and independence of action.

Later use

After the mid-seventeenth century, armies that adopted the flintlock musket began to abandon the pike altogether, or to greatly decrease their numbers. Instead, a bayonet could be affixed to the musket, turning it into a spear, and the musket's firepower was now so deadly that combat was often decided by shooting alone.

A common end date for the use of the pike in infantry formations is 1700, although Prussian and Austrian armies had already abandoned the pike by that date, whereas others such as the Swedish and Russians continued to use it for several decades afterward—the Swedes of King Charles XII in particular using it to great effect until 1721.

Even later, the obsolete pike would still find a use in such countries as Ireland, Russia and China, generally in the hands of desperate peasant rebels who did not have access to decent firearms.

One attempt to resurrect the pike as a primary infantry weapon occurred during the American Civil War when the Confederate States of America planned to recruit twenty regiments of pikemen in 1862. In April 1862 it was authorized that every Confederate infantry regiment would include two companies of pikemen, a plan supported by Robert E. Lee. Many pikes were produced but were never used in battle and the plan to include pikemen in the army was abandoned.

See also

- The Pike & Shot Society, a society devoted to study of the period

References

- Arfaioli, Maurizio. The Black Bands of Giovanni: Infantry and Diplomacy During the Italian Wars (1526–1528). Pisa: Pisa University Press, Edizioni Plus, 2005. ISBN 88-8492-231-3.

- Baumgartner, Frederic J. The French Reluctance to Adopt Firearms Technology in the Early Modern Period, in The Heirs of Archimedes: Science and the Art of War Through the Age of Enlightenment, eds Brett D. Steele and Tamera Dorland. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2005.

- Baumgartner, Frederic J. France in the Sixteenth Century. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1995.

- Oman, Charles. A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century. London: Methuen & Co., 1937.

- Jorgensen, Christer (et al.). Fighting Techniques of the Early Modern World: Equipment, Combat Skills, and Tactics. New York, New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2006.

- Schürger, André. The Battle of Lützen: an examination of 17th century military material culture. University of Glasgow, 2015

- Taylor, Frederick Lewis. The Art of War in Italy, 1494–1529. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1973. ISBN 0-8371-5025-6.