Antihypertensive drug

Antihypertensives are a class of drugs that are used to treat hypertension (high blood pressure).[1] Antihypertensive therapy seeks to prevent the complications of high blood pressure, such as stroke and myocardial infarction. Evidence suggests that reduction of the blood pressure by 5 mmHg can decrease the risk of stroke by 34%, of ischaemic heart disease by 21%, and reduce the likelihood of dementia, heart failure, and mortality from cardiovascular disease.[2] There are many classes of antihypertensives, which lower blood pressure by different means. Among the most important and most widely used medications are thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARBs), and beta blockers.

Which type of medication to use initially for hypertension has been the subject of several large studies and resulting national guidelines. The fundamental goal of treatment should be the prevention of the important endpoints of hypertension, such as heart attack, stroke and heart failure. Patient age, associated clinical conditions and end-organ damage also play a part in determining dosage and type of medication administered.[3] The several classes of antihypertensives differ in side effect profiles, ability to prevent endpoints, and cost. The choice of more expensive agents, where cheaper ones would be equally effective, may have negative impacts on national healthcare budgets.[4] As of 2018, the best available evidence favors low-dose thiazide diuretics as the first-line treatment of choice for high blood pressure when drugs are necessary.[5] Although clinical evidence shows calcium channel blockers and thiazide-type diuretics are preferred first-line treatments for most people (from both efficacy and cost points of view), an ACE inhibitor is recommended by NICE in the UK for those under 55 years old.[6]

Diuretics

Diuretics help the kidneys eliminate excess salt and water from the body's tissues and blood.

- Loop diuretics:

- bumetanide

- ethacrynic acid

- furosemide

- torsemide

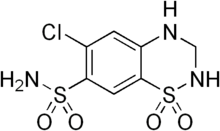

- Thiazide diuretics:

- Thiazide-like diuretics:

- indapamide

- chlorthalidone

- metalozone

- Xipamide

- Clopamide

- Potassium-sparing diuretics:

In the United States, the JNC8 (Eighth Joint National Committee on the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure) recommends thiazide-type diuretics to be one of the first-line drug treatments for hypertension, either as monotherapy or in combination with calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin II receptor antagonists.[7] There are fixed-dose combination drugs, such as ACE inhibitor and thiazide combinations. Despite thiazides being cheap and effective, they are not prescribed as often as some newer drugs. This is because they have been associated with increased risk of new-onset diabetes and as such are recommended for use in patients over 65 where the risk of new-onset diabetes is outweighed by the benefits of controlling systolic blood pressure.[8] Another theory is that they are off-patent and thus rarely promoted by the drug industry.[9]

Calcium channel blockers

Calcium channel blockers block the entry of calcium into muscle cells in artery walls.

- dihydropyridines:

- non-dihydropyridines:

The 8th Joint National Committee (JNC-8) recommends calcium channel blockers to be a first-line treatment either as monotherapy or in combination with thiazide-type diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin II receptor antagonists for all patients regardless of age or race.[7]

The ratio of CCBs' anti-proteinuria effect, non-dihydropyridine to dihydropyridine was 30 to -2.[10]

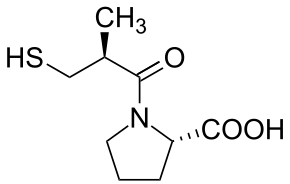

ACE inhibitors

ACE inhibitors inhibit the activity of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), an enzyme responsible for the conversion of angiotensin I into angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor.

- captopril

- enalapril

- fosinopril

- lisinopril

- moexipril

- perindopril

- quinapril

- ramipril

- trandolapril

- benazepril

A systematic review of 63 trials with over 35,000 participants indicated ACE inhibitors significantly reduced doubling of serum creatinine levels compared to other drugs (ARBs, α blockers, β blockers, etc.), and the authors suggested this as a first line of defense.[11] The AASK trial showed that ACE inhibitors are more effective at slowing down the decline of kidney function compared to calcium channel blockers and beta blockers.[12] As such, ACE inhibitors should be the drug treatment of choice for patients with chronic kidney disease regardless of race or diabetic status.[7]

However, ACE inhibitors (and angiotensin II receptor antagonists) should not be a first-line treatment for black hypertensives without chronic kidney disease.[7] Results from the ALLHAT trial showed that thiazide-type diuretics and calcium channel blockers were both more effective as monotherapy in improving cardiovascular outcomes compared to ACE inhibitors for this subgroup.[13] Furthermore, ACE inhibitors were less effective in reducing blood pressure and had a 51% higher risk of stroke in black hypertensives when used as initial therapy compared to a calcium channel blocker.[14] There are fixed-dose combination drugs, such as ACE inhibitor and thiazide combinations.

Notable side effects of ACE inhibitors include dry cough, high blood levels of potassium, fatigue, dizziness, headaches, loss of taste and a risk for angioedema.[15]

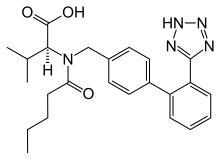

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists work by antagonizing the activation of angiotensin receptors.

In 2004, an article in the BMJ examined the evidence for and against the suggestion that angiotensin receptor blockers may increase the risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack).[16] The matter was debated in 2006 in the medical journal of the American Heart Association.[17][18] There is no consensus on whether ARBs have a tendency to increase MI, but there is also no substantive evidence to indicate that ARBs are able to reduce MI.

In the VALUE trial, the angiotensin II receptor blocker valsartan produced a statistically significant 19% (p=0.02) relative increase in the prespecified secondary end point of myocardial infarction (fatal and non-fatal) compared with amlodipine.[19]

The CHARM-alternative trial showed a significant +52% (p=0.025) increase in myocardial infarction with candesartan (versus placebo) despite a reduction in blood pressure.[20]

Indeed, as a consequence of AT1 blockade, ARBs increase Angiotensin II levels several-fold above baseline by uncoupling a negative-feedback loop. Increased levels of circulating Angiotensin II result in unopposed stimulation of the AT2 receptors, which are, in addition upregulated. Unfortunately, recent data suggest that AT2 receptor stimulation may be less beneficial than previously proposed and may even be harmful under certain circumstances through mediation of growth promotion, fibrosis, and hypertrophy, as well as proatherogenic and proinflammatory effects.[21][22][23]

ARBs happens to be the favorable alternative to ACE inhibitors if the hypertensive patients with the heart failure type of reduced ejection fraction treated with ACEis was intolerant of cough, angioedema other than hyperkalemia or chronic kidney disease.[24][25][26]

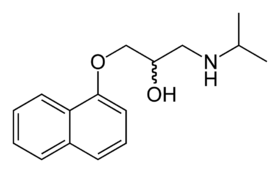

Adrenergic receptor antagonists

- Beta blockers

- Alpha blockers:

- Mixed Alpha + Beta blockers:

Although beta blockers lower blood pressure, they do not have a positive benefit on endpoints as some other antihypertensives.[27] In particular, beta-blockers are no longer recommended as first-line treatment due to relative adverse risk of stroke and new-onset of type 2 diabetes when compared to other medications,[3] while certain specific beta-blockers such as atenolol appear to be less useful in overall treatment of hypertension than several other agents.[28] A systematic review of 63 trials with over 35,000 participants indicated β-blockers increased the risk of mortality, compared to other antihypertensive therapies.[11] They do, however, have an important role in the prevention of heart attacks in people who have already had a heart attack.[29] In the United Kingdom, the June 2006 "Hypertension: Management of Hypertension in Adults in Primary Care"[30] guideline of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, downgraded the role of beta-blockers due to their risk of provoking type 2 diabetes.[31]

Despite lowering blood pressure, alpha blockers have significantly poorer endpoint outcomes than other antihypertensives, and are no longer recommended as a first-line choice in the treatment of hypertension.[32] However, they may be useful for some men with symptoms of prostate disease.

Vasodilators

Vasodilators act directly on the smooth muscle of arteries to relax their walls so blood can move more easily through them; they are only used in hypertensive emergencies or when other drugs have failed, and even so are rarely given alone.

Sodium nitroprusside, a very potent, short-acting vasodilator, is most commonly used for the quick, temporary reduction of blood pressure in emergencies (such as malignant hypertension or aortic dissection).[33][34] Hydralazine and its derivatives are also used in the treatment of severe hypertension, although they should be avoided in emergencies.[34] They are no longer indicated as first-line therapy for high blood pressure due to side effects and safety concerns, but hydralazine remains a drug of choice in gestational hypertension.[33]

Renin inhibitors

Renin comes one level higher than angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in the renin–angiotensin system. Renin inhibitors can therefore effectively reduce hypertension. Aliskiren (developed by Novartis) is a renin inhibitor which has been approved by the U.S. FDA for the treatment of hypertension.[35]

Aldosterone receptor antagonist

Aldosterone receptor antagonists:

Aldosterone receptor antagonists are not recommended as first-line agents for blood pressure,[36] but spironolactone and eplerenone are both used in the treatment of heart failure and resistant hypertension.

Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists

Central alpha agonists lower blood pressure by stimulating alpha-receptors in the brain which open peripheral arteries easing blood flow. These alpha 2 receptors are known as autoreceptors which provide a negative feedback in neurotransmission (in this case, the vasoconstriction effects of adrenaline). Central alpha agonists, such as clonidine, are usually prescribed when all other anti-hypertensive medications have failed. For treating hypertension, these drugs are usually administered in combination with a diuretic.

Adverse effects of this class of drugs include sedation, drying of the nasal mucosa and rebound hypertension.

Some indirect anti-adrenergics are rarely used in treatment-resistant hypertension:

- guanethidine - replaces norepinephrine in vesicles, decreasing its tonic release

- mecamylamine - antinicotinic and ganglion blocker

- reserpine - indirect via irreversible VMAT inhibition

For the most resistant and severe disease, oral minoxidil (Loniten) in combination with diuretic and β-blocker or other sympathetic nervous system suppressant may be used.

Endothelium receptor blockers

Bosentan belongs to a new class of drug and works by blocking endothelin receptors. It is specifically indicated only for the treatment of pulmonary artery hypertension in patients with moderate to severe heart failure.

Choice of initial medication

For mild blood pressure elevation, consensus guidelines call for medically supervised lifestyle changes and observation before recommending initiation of drug therapy. However, according to the American Hypertension Association, evidence of sustained damage to the body may be present even prior to observed elevation of blood pressure. Therefore, the use of hypertensive medications may be started in individuals with apparent normal blood pressures but who show evidence of hypertension-related nephropathy, proteinuria, atherosclerotic vascular disease, as well as other evidence of hypertension-related organ damage.

If lifestyle changes are ineffective, then drug therapy is initiated, often requiring more than one agent to effectively lower hypertension. Which type of many medications should be used initially for hypertension has been the subject of several large studies and various national guidelines. Considerations include factors such as age, race, and other medical conditions.[36] In the United States, JNC8 (2014) recommends any drug from one of the four following classes to be a good choice as either initial therapy or as an add-on treatment: thiazide-type diuretics, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin II receptor antagonists.[7]

The first large study to show a mortality benefit from antihypertensive treatment was the VA-NHLBI study, which found that chlorthalidone was effective.[37] The largest study, Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) in 2002, concluded that chlorthalidone, (a thiazide-like diuretic) was as effective as lisinopril (an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor) or amlodipine (a calcium channel blocker).[13] (ALLHAT showed that doxazosin, an alpha-adrenergic receptor blocker, had a higher incidence of heart failure events, and the doxazosin arm of the study was stopped.)

A subsequent smaller study (ANBP2) did not show the slight advantages in thiazide diuretic outcomes observed in the ALLHAT study, and actually showed slightly better outcomes for ACE-inhibitors in older white male patients.[38]

Thiazide diuretics are effective, recommended as the best first-line drug for hypertension,[39] and are much more affordable than other therapies, yet they are not prescribed as often as some newer drugs. Chlorthalidone is the thiazide drug that is most strongly supported by the evidence as providing a mortality benefit; in the ALLHAT study, a chlorthalidone dose of 12.5 mg was used, with titration up to 25 mg for those subjects who did not achieve blood pressure control at 12.5 mg. Chlorthalidone has repeatedly been found to have a stronger effect on lowering blood pressure than hydrochlorothiazide, and hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone have a similar risk of hypokalemia and other adverse effects at the usual doses prescribed in routine clinical practice.[40] Patients with an exaggerated hypokalemic response to a low dose of a thiazide diuretic should be suspected to have hyperaldosteronism, a common cause of secondary hypertension.

Other medications have a role in treating hypertension. Adverse effects of thiazide diuretics include hypercholesterolemia, and impaired glucose tolerance with increased risk of developing Diabetes mellitus type 2. The thiazide diuretics also deplete circulating potassium unless combined with a potassium-sparing diuretic or supplemental potassium. Some authors have challenged thiazides as first line treatment.[41][42][43] However, as the Merck Manual of Geriatrics notes, "thiazide-type diuretics are especially safe and effective in the elderly."[44]

Current UK guidelines suggest starting patients over the age of 55 years and all those of African/Afrocaribbean ethnicity firstly on calcium channel blockers or thiazide diuretics, whilst younger patients of other ethnic groups should be started on ACE-inhibitors. Subsequently, if dual therapy is required to use ACE-inhibitor in combination with either a calcium channel blocker or a (thiazide) diuretic. Triple therapy is then of all three groups and should the need arise then to add in a fourth agent, to consider either a further diuretic (e.g. spironolactone or furosemide), an alpha-blocker or a beta-blocker.[45] Prior to the demotion of beta-blockers as first line agents, the UK sequence of combination therapy used the first letter of the drug classes and was known as the "ABCD rule".[45][46]

Patient factors

The choice between the drugs is to a large degree determined by the characteristics of the patient being prescribed for, the drugs' side-effects, and cost. Most drugs have other uses; sometimes the presence of other symptoms can warrant the use of one particular antihypertensive. Examples include:

- Age can affect the choice of medications. Current UK guidelines suggest starting patients over the age of 55 years first on calcium channel blockers or thiazide diuretics.

- Age and multi-morbidity can affect the choice of medication, the target blood pressure and even whether to treat or not.[47]

- Anxiety may be improved with the use of beta blockers.

- Asthmatics have been reported to have worsening symptoms when using beta blockers.

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia may be improved with the use of an alpha blocker.

- Chronic kidney disease. ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be included in the treatment plan to improve kidney outcomes regardless of race or diabetic status.[7][12]

- Late-stage Dementia should consider Deprescribing antihypertensives, according to the Medication Appropriateness Tool for Comorbid Health Conditions in Dementia (MATCH-D)[48]

- Diabetes mellitus. The ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers have been shown to prevent the kidney and retinal complications of diabetes mellitus.

- Gout may be worsened by thiazide diuretics, while losartan reduces serum urate.[49]

- Kidney stones may be improved with the use of thiazide-type diuretics [50]

- Heart block. β-blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers should not be used in patients with heart block greater than first degree. JNC8 does not recommend β-blockers as initial therapy for hypertension [51]

- Heart failure may be worsened with nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, the alpha blocker doxazosin, and the alpha-2 agonists moxonidine and clonidine. On the other hand, β-blockers, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and aldosterone receptor antagonists have been shown to improve outcome.[52]

- Pregnancy. Although α-methyldopa is generally regarded as a first-line agent, labetalol and metoprolol are also acceptable. Atenolol has been associated with intrauterine growth retardation, as well as decreased placental growth and weight when prescribed during pregnancy. ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are contraindicated in women who are or who intend to become pregnant.[36]

- Periodontal disease could mitigate the efficacy of antihypertensive drugs.[53]

- Race. JNC8 guidelines particularly point out that when used as monotherapy, thiazide diuretics, and calcium channel blockers have been found to be more effective in reducing blood pressure in black hypertensives than β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, or ARBs.[7]

- Tremor may warrant the use of beta blockers.

The JNC8 guidelines indicate reasons to choose one drug over the others for certain individual patients.[7]

History

Chlorothiazide was discovered in 1957, but the first known instance of an effective antihypertensive treatment was in 1947 using Primaquine, an antimalarial.[54]

Research

Blood pressure vaccines

Vaccinations are being trialed and may become a treatment option for high blood pressure in the future. CYT006-AngQb was only moderately successful in studies, but similar vaccines are being investigated.[55]

References

- Antihypertensive+Agents at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Law M, Wald N, Morris J (2003). "Lowering blood pressure to prevent myocardial infarction and stroke: a new preventive strategy". Health Technology Assessment. 7 (31): 1–94. doi:10.3310/hta7310. PMID 14604498.

- Nelson, Mark. "Drug treatment of elevated blood pressure". Australian Prescriber (33): 108–112. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- Nelson MR, McNeil JJ, Peeters A, Reid CM, Krum H (June 2001). "PBS/RPBS cost implications of trends and guideline recommendations in the pharmacological management of hypertension in Australia, 1994-1998". The Medical Journal of Australia. 174 (11): 565–8. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143436.x. PMID 11453328.

- Wright JM, Musini VM, Gill R (April 2018). Wright JM (ed.). "First-line drugs for hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD001841. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub3. PMC 6513559. PMID 29667175.

- "Hypertension: Management of hypertension in adults in primary care | Guidance | NICE" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-01-07. Retrieved 2012-01-09., p19

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT, Narva AS, Ortiz E (February 2014). "2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PMID 24352797.

- Zillich AJ, Garg J, Basu S, Bakris GL, Carter BL (August 2006). "Thiazide diuretics, potassium, and the development of diabetes: a quantitative review". Hypertension. 48 (2): 219–24. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000231552.10054.aa. PMID 16801488.

- Wang TJ, Ausiello JC, Stafford RS (April 1999). "Trends in antihypertensive drug advertising, 1985-1996". Circulation. 99 (15): 2055–7. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.99.15.2055. PMID 10209012.

- Bakris GL, Weir MR, Secic M, Campbell B, Weis-McNulty A (June 2004). "Differential effects of calcium antagonist subclasses on markers of nephropathy progression". Kidney International. 65 (6): 1991–2002. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00620.x. PMID 15149313.

- Wu HY, Huang JW, Lin HJ, Liao WC, Peng YS, Hung KY, Wu KD, Tu YK, Chien KL (October 2013). "Comparative effectiveness of renin-angiotensin system blockers and other antihypertensive drugs in patients with diabetes: systematic review and bayesian network meta-analysis". BMJ. 347: f6008. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6008. PMC 3807847. PMID 24157497.

- Wright JT, Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Cheek D, Douglas-Baltimore JG, Gassman J, Glassock R, Hebert L, Jamerson K, Lewis J, Phillips RA, Toto RD, Middleton JP, Rostand SG (November 2002). "Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial". JAMA. 288 (19): 2421–31. doi:10.1001/jama.288.19.2421. PMID 12435255.

- The Allhat Officers And Coordinators For The Allhat Collaborative Research Group (December 2002). "Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)". JAMA. 288 (23): 2981–97. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. PMID 12479763.

- Leenen FH, Nwachuku CE, Black HR, Cushman WC, Davis BR, Simpson LM, Alderman MH, Atlas SA, Basile JN, Cuyjet AB, Dart R, Felicetta JV, Grimm RH, Haywood LJ, Jafri SZ, Proschan MA, Thadani U, Whelton PK, Wright JT (September 2006). "Clinical events in high-risk hypertensive patients randomly assigned to calcium channel blocker versus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial". Hypertension. 48 (3): 374–84. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000231662.77359.de. PMID 16864749.

- "High blood pressure (hypertension) - Uses for ACE inhibitors". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2016-08-01. Retrieved 2016-07-27. Page updated: June 29, 2016

- Verma S, Strauss M (November 2004). "Angiotensin receptor blockers and myocardial infarction". BMJ. 329 (7477): 1248–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7477.1248. PMC 534428. PMID 15564232.

- Strauss MH, Hall AS (August 2006). "Angiotensin receptor blockers may increase risk of myocardial infarction: unraveling the ARB-MI paradox". Circulation. 114 (8): 838–54. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594986. PMID 16923768.

- Tsuyuki RT, McDonald MA (August 2006). "Angiotensin receptor blockers do not increase risk of myocardial infarction". Circulation. 114 (8): 855–60. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594978. PMID 16923769.

- Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, Brunner HR, Ekman S, Hansson L, Hua T, Laragh J, McInnes GT, Mitchell L, Plat F, Schork A, Smith B, Zanchetti A (June 2004). "Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial". Lancet. 363 (9426): 2022–31. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16451-9. PMID 15207952.

- Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, Held P, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K (September 2003). "Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial". Lancet. 362 (9386): 772–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5. PMID 13678870.

- Levy BI (September 2005). "How to explain the differences between renin angiotensin system modulators". American Journal of Hypertension. 18 (9 Pt 2): 134S–141S. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.005. PMID 16125050.

- Lévy BI (January 2004). "Can angiotensin II type 2 receptors have deleterious effects in cardiovascular disease? Implications for therapeutic blockade of the renin-angiotensin system". Circulation. 109 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000096609.73772.C5. PMID 14707017.

- Reudelhuber TL (December 2005). "The continuing saga of the AT2 receptor: a case of the good, the bad, and the innocuous". Hypertension. 46 (6): 1261–2. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000193498.07087.83. PMID 16286568.

- Yusuf S, Pitt B, Davis CE, Hood WB, Cohn JN (August 1991). "Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure". The New England Journal of Medicine. 325 (5): 293–302. doi:10.1056/nejm199108013250501. PMID 2057034.

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos G, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW, Westlake C (September 2016). "2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America". Circulation. 134 (13): e282-93. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000435. PMID 27208050.

- Li, Edmond CK; Heran, Balraj S; Wright, James M (22 August 2014). "Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers for primary hypertension". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (8): CD009096. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009096.pub2. PMC 6486121. PMID 25148386.

- Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O (29 Oct – 4 Nov 2005). "Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta-analysis". Lancet. 366 (9496): 1545–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67573-3. PMID 16257341.

- Carlberg B, Samuelsson O, Lindholm LH (6–12 Nov 2004). "Atenolol in hypertension: is it a wise choice?". Lancet. 364 (9446): 1684–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17355-8. PMID 15530629.

- Freemantle N, Cleland J, Young P, Mason J, Harrison J (June 1999). "beta Blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis". BMJ. 318 (7200): 1730–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.318.7200.1730. PMC 31101. PMID 10381708.

- "Hypertension: management of hypertension in adults in primary care". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-16. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- Sheetal Ladva (2006-06-28). "NICE and BHS launch updated hypertension guideline". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

- ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group (September 2003). "Diuretic versus alpha-blocker as first-step antihypertensive therapy: final results from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)". Hypertension. 42 (3): 239–46. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000086521.95630.5A. PMID 12925554.

- Brunton L, Parker K, Blumenthal D, Buxton I (2007). "Therapy of hypertension". Goodman & Gilman's Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 544–60. ISBN 978-0-07-144343-2.

- Varon J, Marik PE (July 2000). "The diagnosis and management of hypertensive crises" (Free full text). Chest. 118 (1): 214–27. doi:10.1378/chest.118.1.214. PMID 10893382.

- Mehta, Akul (January 1, 2011). "Direct Renin Inhibitors as Antihypertensive Drugs". Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ (May 2003). "The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report". JAMA. 289 (19): 2560–72. doi:10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. PMID 12748199.

- Perry HM, Goldman AI, Lavin MA, Schnaper HW, Fitz AE, Frohlich ED, Steele B, Rickman HG: Evaluation of drug treatment in mild hypertension: VA-NHLBI feasibility trial. Ann NY Acad Sci 1978,304:267-292

- Wing LM, Reid CM, Ryan P, Beilin LJ, Brown MA, Jennings GL, Johnston CI, McNeil JJ, Macdonald GJ, Marley JE, Morgan TO, West MJ (February 2003). "A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting--enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (7): 583–92. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021716. PMID 12584366.

- Whelton PK, Williams B (November 2018). "The 2018 European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension and 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Blood Pressure Guidelines: More Similar Than Different". JAMA. 320 (17): 1749–1750. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.16755. PMID 30398611.

- https://blogs.pharmacy.umaryland.edu/atrium/2016/05/18/which-thiazide-type-diuretic-should-be-first-line-in-patients-with-hypertension/

- Lewis PJ, Kohner EM, Petrie A, Dollery CT (March 1976). "Deterioration of glucose tolerance in hypertensive patients on prolonged diuretic treatment". Lancet. 1 (7959): 564–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(76)90359-7. PMID 55840.

- Murphy MB, Lewis PJ, Kohner E, Schumer B, Dollery CT (December 1982). "Glucose intolerance in hypertensive patients treated with diuretics; a fourteen-year follow-up". Lancet. 2 (8311): 1293–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(82)91506-9. PMID 6128594.

- Messerli FH, Williams B, Ritz E (August 2007). "Essential hypertension". Lancet. 370 (9587): 591–603. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61299-9. PMID 17707755.

- "Section 11. Cardiovascular Disorders – Chapter 85. Hypertension". Merck Manual of Geriatrics. July 2005. Archived from the original on 2009-01-23.

- "CG34 Hypertension – quick reference guide" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 28 June 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- Williams B (November 2003). "Treatment of hypertension in the UK: simple as ABCD?". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 96 (11): 521–2. doi:10.1258/jrsm.96.11.521. PMC 539621. PMID 14594956.

- Parekh N, Page A, Ali K, Davies K, Rajkumar C (April 2017). "A practical approach to the pharmacological management of hypertension in older people". Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 8 (4): 117–132. doi:10.1177/2042098616682721. PMC 5394506. PMID 28439398.

- Page AT, Potter K, Clifford R, McLachlan AJ, Etherton-Beer C (October 2016). "Medication appropriateness tool for co-morbid health conditions in dementia: consensus recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel". Internal Medicine Journal. 46 (10): 1189–1197. doi:10.1111/imj.13215. PMC 5129475. PMID 27527376.

- Würzner G,"Comparative effects of losartan and irbesartan on serum uric acid in hypertensive patients with hyperuricaemia and gout." J Hypertens. 2001;19(10) 1855.

- Worcester EM, Coe FL: Clinical practice. Calcium kidney stones" N Engl J Med 2010;363(10) 954-963. Worcester EM, Coe FL (September 2010). "Clinical practice. Calcium kidney stones". The New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (10): 954–63. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1001011. PMC 3192488. PMID 20818905.

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure-The JNC 7 Report. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), 2003. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-02-16. Retrieved 2013-02-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, Gersh BJ, Gore J, Izzo JL, Kaplan NM, O'Connor CM, O'Gara PT, Oparil S (May 2007). "Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention". Circulation. 115 (21): 2761–88. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.107.183885. PMID 17502569.

- Pietropaoli D, Del Pinto R, Ferri C, Wright JT, Giannoni M, Ortu E, Monaco A (December 2018). "Poor Oral Health and Blood Pressure Control Among US Hypertensive Adults". Hypertension. 72 (6): 1365–1373. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11528. PMID 30540406.

- Historical Development of Antihypertensive Treatment Archived 2017-02-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Brown MJ (October 2009). "Success and failure of vaccines against renin-angiotensin system components". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 6 (10): 639–47. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2009.156. PMID 19707182.