Proximal tubule

The proximal tubule is the segment of the nephron in kidneys which begins from the renal pole of the Bowman's capsule to the beginning of loop of Henle. It can be further classified into the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) and the proximal straight tubule (PST).

| Proximal tubule | |

|---|---|

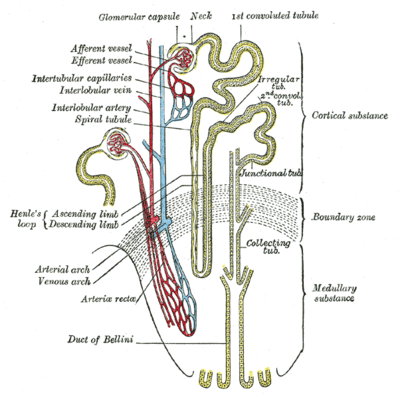

Scheme of renal tubule and its vascular supply. (1st convoluted tubule labeled at center top.) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Metanephric blastema |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tubulus proximalis, pars tubuli proximalis |

| MeSH | D007687 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

The most distinctive characteristic of the proximal tubule is its luminal brush border.

Brush border cell

The luminal surface of the epithelial cells of this segment of the nephron is covered with densely packed microvilli forming a border readily visible under the light microscope giving the brush border cell its name. The microvilli greatly increase the luminal surface area of the cells, presumably facilitating their reabsorptive function as well as putative flow sensing within the lumen.[1]

The cytoplasm of the cells is densely packed with mitochondria, which are largely found in the basal region within the infoldings of the basal plasma membrane. The high quantity of mitochondria gives the cells an acidophilic appearance. The mitochondria are needed in order to supply the energy for the active transport of sodium ions out of the cells to create a concentration gradient which allows more sodium ions to enter the cell from the luminal side. Water passively follows the sodium out of the cell along its concentration gradient.

Cuboidal epithelial cells lining the proximal tubule have extensive lateral interdigitations between neighboring cells, which lend an appearance of having no discrete cell margins when viewed with a light microscope.

Agonal resorption of the proximal tubular contents after interruption of circulation in the capillaries surrounding the tubule often leads to disturbance of the cellular morphology of the proximal tubule cells, including the ejection of cell nuclei into the tubule lumen.

This has led some observers to describe the lumen of proximal tubules as occluded or "dirty-looking", in contrast to the "clean" appearance of distal tubules, which have quite different properties.

Divisions

The proximal tubule as a part of the nephron can be divided into two sections, pars convoluta and pars recta. Differences in cell outlines exist between these segments, and therefore presumably in function too.

Regarding ultrastructure, it can be divided into three segments, oS1, S2, and S3:

| Segment | Gross divisions | Ultrastructure divisions | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal tubule | convoluted | S1[2] | Higher cell complexity[2] |

| S2[2] | |||

| straight | |||

| S3[2] | Lower cell complexity[2] | ||

Proximal convoluted tubule (pars convoluta)

The pars convoluta (Latin "convoluted part") is the initial convoluted portion.

In relation to the morphology of the kidney as a whole, the convoluted segments of the proximal tubules are confined entirely to the renal cortex.

Some investigators on the basis of particular functional differences have divided the convoluted part into two segments designated S1 and S2.

Proximal straight tubule (pars recta)

The pars recta (Latin "straight part") is the following straight (descending) portion.

Straight segments descend into the outer medulla. They terminate at a remarkably uniform level and it is their line of termination that establishes the boundary between the inner and outer stripes of the outer zone of the renal medulla.

As a logical extension of the nomenclature described above, this segment is sometimes designated as S3.

Functions

Absorption

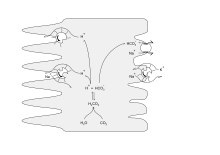

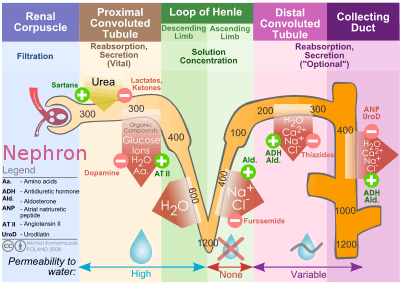

The proximal tubule efficiently regulates the pH of the filtrate by exchanging hydrogen ions in the interstitium for bicarbonate ions in the filtrate; it is also responsible for secreting organic acids, such as creatinine and other bases, into the filtrate.

Fluid in the filtrate entering the proximal convoluted tubule is reabsorbed into the peritubular capillaries. This is driven by sodium transport from the lumen into the blood by the Na+/K+ ATPase in the basolateral membrane of the epithelial cells.

Sodium reabsorption is primarily driven by this P-type ATPase. 60-70% of the filtered sodium load is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule through active transport, solvent drag, and paracellular electrodiffusion. Active transport is mainly through the sodium/hydrogen antiporter NHE3.[3] Paracellular transport increases transport efficiency, as determined by oxygen consumed per unit of Na+ reabsorbed, thus playing a part in maintaining renal oxygen homeostasis.[4]

| Substance | % of filtrate reabsorbed | Comments |

| salt and water | approximately two-thirds | Much of the mass movement of water and solutes occurs through the cells, passively across the basolateral membrane via transcellular transport, followed by active resorption across the apical/luminal membrane via the Na/K/ATPase pump. The solutes are absorbed isotonically, in that the osmotic potential of the fluid leaving the proximal tubule is the same as that of the initial glomerular filtrate. |

| organic solutes (primarily glucose and amino acids) | 100% | Glucose, amino acids, inorganic phosphate, and some other solutes are resorbed via secondary active transport through co-transporters driven by the sodium gradient out of the nephron. |

| potassium | approximately 65% | Most of the filtered potassium is resorbed by two paracellular mechanisms - solvent drag and simple diffusion.[5] |

| urea | approximately 50% | Paracellular fluid reabsorption sweeps some urea with it via solvent drag. As water leaves the lumen, the concentration of urea increases, which facilitates diffusion in the late proximal tubule.[5] |

| phosphate | approximately 80% | Parathyroid hormone reduces reabsorption of phosphate in the proximal tubules, but, because it also enhances the uptake of phosphate from the intestine and bones into the blood, the responses to PTH cancel each other out, and the serum concentration of phosphate remains approximately the same. |

| citrate | 70%–90%[6] | Acidosis increases absorption. Alkalosis decreases absorption. |

Secretion

Many types of medications are secreted in the proximal tubule. Further reading: Table of medication secreted in kidney

Most of the ammonium that is excreted in the urine is formed in the proximal tubule via the breakdown of glutamine to alpha-ketoglutarate.[7] This takes place in two steps, each of which generates an ammonium anion: the conversion of glutamine to glutamate and the conversion of glutamate to alpha-ketoglutarate.[7] The alpha-ketoglutarate generated in this process is then further broken down to form two bicarbonate anions,[7] which are pumped out of the basolateral portion of the tubule cell by co-transport with sodium ions.

Clinical significance

Proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTECs) have a pivotal role in kidney disease. Two mammalian cell lines are commonly used as models of the proximal tubule: porcine LLC-PK1 cells and marsupial OK cells.[8]

Cancer

Most renal cell carcinoma, the most common form of kidney cancer, arises from the convoluted tubules.[9]

Other

Acute tubular necrosis occurs when PTECs are directly damaged by toxins such as antibiotics (e.g., gentamicin), pigments (e.g., myoglobin) and sepsis (e.g., mediated by lipopolysaccharide from gram-negative bacteria). Renal tubular acidosis (proximal type) (Fanconi syndrome) occurs when the PTECs are unable to properly reabsorb glomerular filtrate so that there is increased loss of bicarbonate, glucose, amino acids, and phosphate.

PTECs also participate in the progression of tubulointerstitial injury due to glomerulonephritis, ischemia, interstitial nephritis, vascular injury, and diabetic nephropathy. In these situations, PTECs may be directly affected by protein (e.g., proteinuria in glomerulonephritis), glucose (in diabetes mellitus), or cytokines (e.g., interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factors). There are several ways in which PTECs may respond: producing cytokines, chemokines, and collagen; undergoing epithelial mesenchymal trans-differentiation; necrosis or apoptosis.

See also

- Urinary pole

- Brush border

Additional images

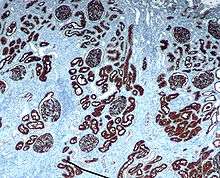

Distribution of blood vessels in cortex of kidney.

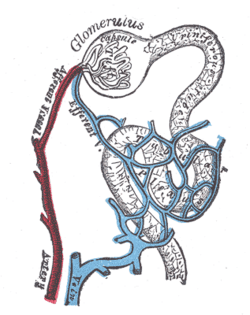

Distribution of blood vessels in cortex of kidney. Glomerulus.

Glomerulus. TEM of negatively stained proximal convoluted tubule of Rat kidney tissue at a magnification of ~55,000x and 80KV with Tight junction.

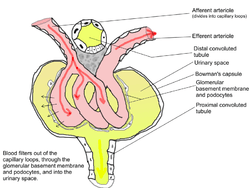

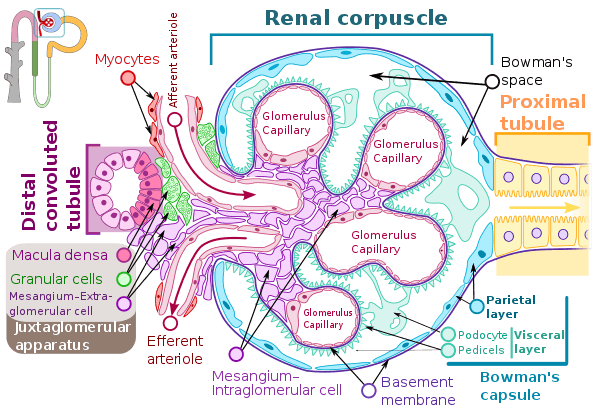

TEM of negatively stained proximal convoluted tubule of Rat kidney tissue at a magnification of ~55,000x and 80KV with Tight junction. Renal corpuscle

Renal corpuscle Diagram outlining movement of ions in nephron.

Diagram outlining movement of ions in nephron.

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1223 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Wang T (September 2006). "Flow-activated transport events along the nephron". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 15 (5): 530–6. doi:10.1097/01.mnh.0000242180.46362.c4. PMID 16914967.

- Boron WF, Boulpaep EL, eds. (2005). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approaoch. Elsevier/Saunders. p. 743. ISBN 978-1-4160-2328-9.

- Aronson PS (2002). "Ion exchangers mediating NaCl transport in the renal proximal tubule". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 36 (2–3): 147–53. doi:10.1385/CBB:36:2-3:147. PMID 12139400.

- Pei L, Solis G, Nguyen MT, Kamat N, Magenheimer L, Zhuo M, Li J, Curry J, McDonough AA, Fields TA, Welch WJ, Yu AS (July 2016). "Paracellular epithelial sodium transport maximizes energy efficiency in the kidney". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 126 (7): 2509–18. doi:10.1172/JCI83942. PMC 4922683. PMID 27214555.

- Boron WF, Boulpaep EL, eds. (2005). Medical Physiology (Updated ed.).

- Hypocitraturia~overview#aw2aab6b5 at eMedicine

- Rose BD, Rennke HG (1994). Renal pathophysiology : the essentials. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-683-07354-6.

- Kruidering M, van de Water B, Nagelkerke JF (1996). Methods for studying renal toxicity. Archives of Toxicology. Supplement. Archives of Toxicology. 18. pp. 173–83. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-61105-6. ISBN 978-3-642-64696-6. PMID 8678793.

- Tomita Y (February 2006). "Early renal cell cancer". International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 11 (1): 22–7. doi:10.1007/s10147-005-0551-4. PMID 16508725.

External links

- Anatomy photo: Urinary/mammal/cortex1/cortex6 - Comparative Organology at University of California, Davis - "Mammal, kidney cortex (LM, Medium)"

- Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 7/7ch03/7ch03p14". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24. - "The Nephron: Proximal Tubule, Pars Convoluta & Pars Recta"

- Swiss embryology (from UL, UB, and UF) turinary/urinhaute02