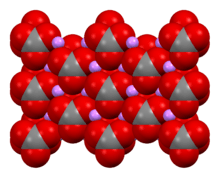

Lithium carbonate

Lithium carbonate is an inorganic compound, the lithium salt of carbonate with the formula Li

2CO

3. This white salt is widely used in the processing of metal oxides and treatment of mood disorders.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Lithium carbonate | |

| Other names

Dilithium carbonate, Carbolith, Cibalith-S, Duralith, Eskalith, Lithane, Lithizine, Lithobid, Lithonate, Lithotabs Priadel, Zabuyelite | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.239 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Li 2CO 3 | |

| Molar mass | 73.89 g/mol |

| Appearance | Odorless white powder |

| Density | 2.11 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 723 °C (1,333 °F; 996 K) |

| Boiling point | 1,310 °C (2,390 °F; 1,580 K) Decomposes from ~1300 °C |

| |

| Solubility | Insoluble in acetone, ammonia, alcohol[2] |

| −27.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD) |

1.428[3] |

| Viscosity |

|

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C) |

97.4 J/mol·K[2] |

Std molar entropy (S |

90.37 J/mol·K[2] |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−1215.6 kJ/mol[2] |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG˚) |

−1132.4 kJ/mol[2] |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Irritant |

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 1109 |

| GHS pictograms |  |

| GHS Signal word | Warning |

GHS hazard statements |

H302, H319[4] |

| P305+351+338[4] | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

525 mg/kg (oral, rat)[5] |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations |

Sodium carbonate Potassium carbonate Rubidium carbonate Caesium carbonate |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

For the treatment of bipolar disorder, it is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[6]

Uses

Lithium carbonate is an important industrial chemical. It forms low-melting fluxes with silica and other materials. Glasses derived from lithium carbonate are useful in ovenware. Lithium carbonate is a common ingredient in both low-fire and high-fire ceramic glaze. Its alkaline properties are conducive to changing the state of metal oxide colorants in glaze particularly red iron oxide (Fe

2O

3). Cement sets more rapidly when prepared with lithium carbonate, and is useful for tile adhesives. When added to aluminium trifluoride, it forms LiF which gives a superior electrolyte for the processing of aluminium.[7] It is also used in the manufacture of most lithium-ion battery cathodes, which are made of lithium cobalt oxide.

Medical uses

In 1843, lithium carbonate was used as a new solvent for stones in the bladder. In 1859, some doctors recommended a therapy with lithium salts for a number of ailments, including gout, urinary calculi, rheumatism, mania, depression, and headache. In 1948, John Cade discovered the antimanic effects of lithium ions. This finding led lithium, specifically lithium carbonate, to be used to treat mania associated with bipolar disorder.

Lithium carbonate is used to treat mania, the elevated phase of bipolar disorder. Lithium ions interfere with ion transport processes (see “sodium pump”) that relay and amplify messages carried to the cells of the brain.[8] Mania is associated with irregular increases in protein kinase C (PKC) activity within the brain. Lithium carbonate and sodium valproate, another drug traditionally used to treat the disorder, act in the brain by inhibiting PKC's activity and help to produce other compounds that also inhibit the PKC.[9] Lithium carbonate's mood-controlling properties are not fully understood.[10]

Adverse reactions

Taking lithium salts has risks and side effects. Extended use of lithium to treat various mental disorders has been known to lead to acquired nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.[11] Lithium intoxication can affect the central nervous system and renal system and can be lethal.[12]

Red colorant

Lithium carbonate is used to impart a red color to fireworks.[13].

Properties and reactions

Unlike sodium carbonate, which forms at least three hydrates, lithium carbonate exists only in the anhydrous form.[14] Its solubility in water is low relative to other lithium salts. The isolation of lithium from aqueous extracts of lithium ores capitalizes on this poor solubility. Its apparent solubility increases 10-fold under a mild pressure of carbon dioxide; this effect is due to the formation of the metastable bicarbonate, which is more soluble:[7]

- Li

2CO

3 + CO

2 + H

2O ⇌ 2 LiHCO

3

The extraction of lithium carbonate at high pressures of CO

2 and its precipitation upon depressuring is the basis of the Quebec process.

Lithium carbonate can also be purified by exploiting its diminished solubility in hot water. Thus, heating a saturated aqueous solution causes crystallization of Li

2CO

3.[15]

Lithium carbonate, and other carbonates of group 1, do not decarboxylate readily. Li

2CO

3 decomposes at temperatures around 1300 °C.

Production

Lithium is extracted from primarily two sources: pegmatite crystals and lithium salt from brine pools. About 30,000 tons were produced in 1989. It also exists as the rare mineral zabuyelite.[16]

Lithium carbonate is generated by combining lithium peroxide with carbon dioxide. This reaction is the basis of certain air purifiers, e.g., in spacecraft, used to absorb carbon dioxide:[14]

- 2 Li

2O

2 + 2 CO

2 → 2 Li

2CO

3 + O

2

In recent years many junior mining companies have begun exploration of lithium projects throughout North America, South America and Australia to identify economic deposits that can potentially bring new supplies of lithium carbonate online to meet the growing demand for the product. [17]

In April 2017 MGX Minerals reported it had received independent confirmation of its rapid lithium extraction process to recover lithium and other valuable minerals from oil and gas wastewater brine. [18]

Natural occurrence

Natural lithium carbonate is known as zabuyelite. This mineral is connected with deposits of some salt lakes and some pegmatites.[19]

References

- Seidell, Atherton; Linke, William F. (1952). Solubilities of Inorganic and Organic Compounds. Van Nostrand.

- "lithium carbonate". Chemister.ru. 2007-03-19. Retrieved 2017-01-02.

- Pradyot Patnaik. Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill, 2002, ISBN 0-07-049439-8

- Sigma-Aldrich Co., Lithium carbonate. Retrieved on 2014-06-03.

- Michael Chambers. "ChemIDplus - 554-13-2 - XGZVUEUWXADBQD-UHFFFAOYSA-L - Lithium carbonate [USAN:USP:JAN] - Similar structures search, synonyms, formulas, resource links, and other chemical information". Chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2017-01-02.

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Ulrich Wietelmann, Richard J. Bauer (2005). "Lithium and Lithium Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_393.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "lithium, Lithobid: Drug Facts, Side Effects and Dosing". Medicinenet.com. 2016-06-17. Retrieved 2017-01-02.

- Yildiz, A; Guleryuz, S; Ankerst, DP; Ongür, D; Renshaw, PF (2008). "Protein kinase C inhibition in the treatment of mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tamoxifen" (PDF). Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (3): 255–63. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.43. PMID 18316672.

- Lithium Carbonate at PubChem

- Richard T. Timmer; Jeff M. Sands (1999-03-01). "Lithium Intoxication". Jasn.asnjournals.org. Retrieved 2017-01-02.

- Simard, M; Gumbiner, B; Lee, A; Lewis, H; Norman, D (1989). "Lithium carbonate intoxication. A case report and review of the literature" (PDF). Archives of Internal Medicine. 149 (1): 36–46. doi:10.1001/archinte.149.1.36. PMID 2492186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- "Chemistry of Fireworks".

- Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edn.), Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. Pages=84-85 ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- Caley, E. R.; Elving, P. J. (1939). "Purification of Lithium Carbonate". Inorganic Syntheses. 1: 1–2. doi:10.1002/9780470132326.ch1.

- David Barthelmy. "Zabuyelite Mineral Data". Mineralogy Database. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- "Junior mining companies exploring for lithium". www.juniorminingnetwork.com. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- "MGX Minerals Receives Independent Confirmation of Rapid Lithium Extraction Process". www.juniorminingnetwork.com. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- https://www.mindat.org/min-4380.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lithium carbonate. |

- Official FDA information published by Drugs.com