Antiziganism

Antiziganism (also antigypsyism, anti-Romanyism, Romaphobia, or anti-Romani sentiment) is hostility, prejudice, discrimination or racism which is specifically directed at Romani people (Roma, Sinti, Iberian Kale, Welsh Kale, Finnish Kale and Romanichal). Non-Romani itinerant groups in Europe such as the Yenish and Irish and Scottish Travellers are often given the misnomer "gypsy" and confused with the Romani people. As a result, sentiments which were originally directed at the Romani people are also directed at other traveler groups and they are often referred to as "antigypsy" sentiments.

| Part of a series on |

| Romani people |

|---|

|

Diaspora

|

|

The term Antigypsyism is recognized by the European Parliament and the European Commission as well as by a wide cross-section of civil society.[1]

Etymology

The root Zigan comes from the term Cingane (alt. Tsinganoi, Zigar, Zigeuner) which probably derives from Athinganoi, the name of a Christian sect which the Romani became associated with during the Middle Ages.[2][3][4][5] According to Martin Holler, the English term anti-Gypsyism stems from the mid-1980s, and it became mainstream in the 2000s and 2010s, whereas the term antiziganism was more recently borrowed from the German Antiziganismus.[6]

History

In the Middle Ages

In the early 13th-century Byzantine records, the Atsínganoi are mentioned as "wizards ... who are inspired satanically and pretend to predict the unknown".[7]

Enslavement of Roma, mostly taken as prisoners of war, in the Danubian Principalities is first documented in the late 15th century. In these countries extensive legislation was developed that classified Roma into different groups, according to their tasks as slaves.[8]

By the 16th century, many Romani who lived in Eastern and Central Europe worked as musicians, metal craftsmen, and soldiers.[9] As the Ottoman Empire expanded, it relegated the Romani, who were seen as having "no visible permanent professional affiliation", to the lowest rung of the social ladder.[10]

16th & 17th centuries

In Royal Hungary in the 16th century at the time of the Turkish occupation, the Crown developed strong anti-Romani policies, as these people were considered suspect as Turkish spies or as a fifth column. In this atmosphere, they were expelled from many locations and increasingly adopted a nomadic way of life.[11]

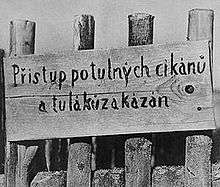

The first anti-Romani legislation was issued in the March of Moravia in 1538, and three years later, Ferdinand I ordered that Romani in his realm be expelled after a series of fires in Prague.

In 1545, the Diet of Augsburg declared that "whosoever kills a Gypsy (Romani), will be guilty of no murder".[12] The subsequent massive killing spree which took place across the empire later prompted the government to step in to "forbid the drowning of Romani women and children".[13]

In England, the Egyptians Act 1530 banned Romani from entering the country and required those living in the country to leave within 16 days. Failure to do so could result in confiscation of property, imprisonment and deportation. The act was amended with the Egyptians Act 1554, which directed that they abandon their "naughty, idle and ungodly life and company" and adopt a settled lifestyle. For those who failed to adhere to a sedentary existence, the Privy council interpreted the act to permit execution of non-complying Romani "as a warning to others".[14]

In 1660, the Romani were prohibited from residing in France by Louis XIV.[15]

18th century

In 1710, Joseph I, Holy Roman Emperor, issued an edict against the Romani, ordering "that all adult males were to be hanged without trial, whereas women and young males were to be flogged and banished forever." In addition, in the kingdom of Bohemia, Romani men were to have their right ears cut off; in the March of Moravia, the left ear was to be cut off. In other parts of Austria, they would be branded on the back with a branding iron, representing the gallows. These mutilations enabled authorities to identify the individuals as Romani on their second arrest. The edict encouraged local officials to hunt down Romani in their areas by levying a fine of 100 Reichsthaler on those who failed to do so. Anyone who helped Romani was to be punished by doing forced labor for half a year. The result was mass killings of Romani across the Holy Roman empire. In 1721, Charles VI amended the decree to include the execution of adult female Romani, while children were "to be put in hospitals for education".[16]

In 1774, Maria Theresa of Austria issued an edict forbidding marriages between Romani. When a Romani woman married a non-Romani, she had to produce proof of "industrious household service and familiarity with Catholic tenets", a male Rom "had to prove his ability to support a wife and children", and "Gypsy children over the age of five were to be taken away and brought up in non-Romani families."[17]

In 2007 the Romanian government established a panel to study the 18th- and 19th-century period of Romani slavery by Princes, local landowners, and monasteries. This officially legalized practice was first documented in the 15th century.[8] Slavery of Romani was outlawed in the Romanian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in around 1856.[18]

19th century

Governments regularly cited petty theft committed by Romani as justification for regulating and persecuting them. In 1899, the Nachrichtendienst für die Sicherheitspolizei in Bezug auf Zigeuner (transl. Intelligence service for the security police concerning gypsies) was set up in Munich under the direction of Alfred Dillmann, and catalogued data on all Romani individuals throughout the German-speaking lands. It did not officially close down until 1970. The results were published in 1905 in Dillmann's Zigeuner-Buch,[19] which was used in the following years as justification for the Porajmos. It described the Romani people as a "plague" and a "menace", but almost exclusively characterized "Gypsy crime" as trespassing and the theft of food.[19]

In the United States during Congressional debate in 1866 over the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution which would subsequently grant citizenship to all persons born within U.S. territory, an objection raised was that a consequence of enacting the amendment would be to grant citizenship to Gypsies and other groups perceived by some as undesirable.[20]

Pennsylvania Senator Edgar Cowan stated,

...I am as liberal as anybody toward the rights of all people, but I am unwilling, on the part of my State, to give up the right that she claims, and that she may exercise, and exercise before very long, of expelling a certain number of people who invade her borders; who owe her no allegiance; who pretend to owe none; who recognize no authority in her government; who have a distinct, independent government of their own—an imperium in imperio; who pay no taxes; who never perform military service; who do nothing, in fact, which becomes a citizen, and perform none of the duties which devolve upon him, but, on the other hand, have no homes, pretend to own no land, live nowhere, settle as trespassers where ever they go, and whose sole merit is a universal swindle; who delight in it, who boast of it, and whose adroitness and cunning is of such a transcendent character that no skill can serve to correct or punish it; I mean the Gypsies. They wander in gangs in my State... These people live in the country and are born in the country. They infest society.

In response Senator John Conness of California observed,

I have lived in the United States now many a year, and really I have heard more about Gypsies within the last two or three months than I have heard before in my life. It cannot be because they have increased so much of late. It cannot be because they have been felt to be particularly oppressive in this or that locality. It must be that the Gypsy element is to be added to our political agitation, so that hereafter the negro alone shall not claim our entire attention.

Porajmos

Persecution of Romani people reached a peak during World War II in the Porajmos (literally, the devouring), a descriptive neologism for the Nazi genocide of Romanis during the Holocaust. Because the Romani communities in Central and Eastern Europe were less organized than the Jewish communities and the Einsatzgruppen, mobile killing squads, who travelled from village to village massacring the Romani inhabitants where they lived typically left few to no records of the number of Roma killed in this way, although in a few cases, significant documentary evidence of mass murder was generated.[22] it is more difficult to assess the actual number of victims. Historians estimate that between 220,000 and 500,000 Romani were killed by the Germans and their collaborators—25% to over 50% of the slightly fewer than 1 million Roma in Europe at the time.[23] A more thorough research by Ian Hancock revealed the death toll to be at about 1.5 million.[24]

Nazi racial ideology put Romani, Jews, Slavs and blacks at the bottom of the racial scale.[25] The German Nuremberg Laws of 1935 stripped Jews of citizenship, confiscated property and criminalized sexual relationship and marriage with Aryans. These laws were extended to Romani as Nazi policy towards Roma and Sinti was complicated by pseudo-historic racialist theories, which could be contradictory, namely that the Romani were of Egyptian ancestry. While they considered Romani grossly inferior, they believed the Roma people had some distant "Aryan" roots that had been corrupted. The Romani are actually a distinctly European people of considerable Northwestern Indian descent, or what is literally considered to be Aryan. Similarly to European Jews, specifically the Ashkenazi, the Romani people quickly acquired European genetics via enslavement and intermarriage upon their arrival in Europe 1,000 years ago.

In the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the Nazi genocide of the Romani was so thorough that it exterminated the majority of Bohemian Romani speakers, eventually leading to the language's extinction in 1970 with the death of its last known speaker, Hana Šebková. In Denmark, Greece and a small number of other countries, resistance by the native population thwarted planned Nazi deportations and extermination of the Romani. In most conquered countries (e.g., the Baltic states), local cooperation with the Nazis expediated the murder of almost all local Romani. In Croatia, the Croatian collaborators of the Ustaše, were so vicious only a minor remnant of Croatian Romani (and Jews) survived the killings.

In 1982, West Germany formally recognized that genocide had been committed against the Romani.[26] Before this they had often claimed that, unlike Jews, Roma and Sinti were not targeted for racial reasons, but for "criminal" reasons, invoking antiziganist stereotype. In modern Holocaust scholarship the Porajmos has been increasingly recognized as a genocide committed simultaneously with the Shoah.[27]

Catholic Church takes responsibility

On 12 March 2000, Pope John Paul II issued a formal public apology to, among other groups of people affected by Catholic persecution, the Romani people and begged God for forgiveness.[28] On 2 June 2019, Pope Francis acknowledged during a meeting with members of the Romanian Romani community the Catholic Church's history of promoting "discrimination, segregation and mistreatment" against Romani people throughout the world, apologized, and asked the Romani people for forgiveness.[29][30][31][32]

Contemporary antiziganism

A 2011 report issued by Amnesty International states, "systematic discrimination is taking place against up to 10 million Roma across Europe. The organization has documented the failures of governments across the continent to live up to their obligations."[33]

Antiziganism has continued well into the 2000s, particularly in Slovakia,[34] Hungary,[35] Slovenia[36] and Kosovo.[37] In Bulgaria, Professor Ognian Saparev has written articles stating that 'Gypsies' are culturally inclined towards theft and use their minority status to 'blackmail' the majority.[38] European Union officials censured both the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 2007 for forcibly segregating Romani children from regular schools.[39]

The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Thomas Hammarberg, has been an outspoken critic of antiziganism. In August 2008, Hammarberg noted that "today's rhetoric against the Roma is very similar to the one used by Nazi Germany before World War II. Once more, it is argued that the Roma are a threat to safety and public health. No distinction is made between a few criminals and the overwhelming majority of the Roma population. This is shameful and dangerous".[40]

According to the latest Human Rights First Hate Crime Survey, Romanis routinely suffer assaults in city streets and other public places as they travel to and from homes and markets. In a number of serious cases of violence against them, attackers have also sought out whole families in their homes or whole communities in settlements predominantly housing Romanis. The widespread patterns of violence are sometimes directed both at causing immediate harm to Romanis, without distinction between adults, the elderly, and small children and physically eradicating the presence of Romani people in towns and cities in several European countries.[41]

Public opinion

The extent of negative attitudes towards Romani people varies across different parts of Europe.

European Union

.svg.png)

The practice of placing Romani students in segregated schools or classes remains widespread in countries across Europe.[44] Many Romani children have been channeled into all-Romani schools that offer inferior quality education and are sometimes in poor physical condition or into segregated all-Romani or predominantly Romani classes within mixed schools.[45] Many Romani children are sent to classes for pupils with learning disabilities. They are also sent to so-called "delinquent schools", with a variety of human rights abuses.[45]

Romani in European cities are often accused of crimes such as pickpocketing. In 2009, a documentary by the BBC called Gypsy Child Thieves showed Romani children being kidnapped and abused by Romani gangs from Romania. The children were often held locked in sheds during the nights and sent to steal during the days.[46] However, Chachipe, a charity which works for the human rights of Romani people, has claimed that this programme promoted "popular stereotypes against Roma which contribute to their marginalisation and provide legitimacy to racist attacks against them" and that in suggesting that begging and child exploitation was "intrinsic to the Romany culture", the programme was "highly damaging" for the Romani people. However, the charity accepted that some of the incidents that were detailed in the programme in fact took place.[47]

The documentary speculated that in Milan, Italy a single Romani child was able to steal as much as €12,000 in a month; and that there were as many as 50 of such abused Romani children operating in the city. The film went on to describe the link between poverty, discrimination, crime and exploitation.[46]

A United Nations study[48] found that Romani people living in European countries are arrested for robbery much more often than other groups. Amnesty International[49] and Romani rights groups such as the Union Romani blame widespread institutionalised racism and persecution.[50] In July 2008, a Business Week feature found the region's Romani population to be a "missed economic opportunity".[51] Hundreds of people from Ostravice, in the Beskydy mountains in Czech Republic, signed a petition against a plan to move Romani families from Ostrava city to their home town, fearing the Romani invasion as well as their schools not being able to cope with the influx of Romani children.[52]

In 2009, the UN's anti-racism panel charged that "Gypsies suffer widespread racism in European Union".[53] The EU has launched a program entitled Decade of Roma Inclusion to combat this and other problems.[54]

Austria

On 5 February 1995, Franz Fuchs killed four Romani in Oberwart with a pipe bomb improvised explosive device which was attached to a sign that read "Roma zurück nach Indien" ("Romani back to India"). It was the worst racial terror attack in post-war Austria, and was Fuchs's first fatal attack.[55]

Bulgaria

In 2011 in Bulgaria, the widespread anti-Romanyism culminated in anti-Roma protests in response to the murder of Angel Petrov on the orders of Kiril Rashkov, a Roma leader in the village of Katunitsa. In the subsequent trial, the killer, Simeon Yosifov, was sentenced to 17 years in jail.[56] As of May 2012, an appeal was under way.

Protests continued on 1 October in Sofia, with 2000 Bulgarians marching against the Romani and what they viewed to be the "impunity and the corruption" of the political elite in the country.[57]

Volen Siderov, leader of the far-right Ataka party and presidential candidate, spoke to a crowd at the Presidential Palace in Sofia, calling for the death penalty to be reinstated as well as Romani ghettos to be dismantled.[57]

Many of the organized protests were accompanied by ethnic clashes and racist violence against Romani. The protesters shouted racist slogans like "Gypsies into soap" and "Slaughter the Turks!"[62] Many protesters were arrested for public order offenses.[63][64] The news media labelled the protests as anti-Romani Pogroms.[62]

Furthermore, in 2009, Bulgarian prime minister Borissov referred to Roma as "bad human material".[58][59][60][61] The vice-president of the Party of European Socialists, Jan Marinus Wiersma claimed that he "has already crossed the invisible line between right-wing populism and extremism".[65]

In 2019 pogroms against the Roma community in Gabrovo broke out after 3 young Romani have been caught stealing in a shop.[66] The following wave of riots saw incidents of violence and arson of two houses where Roma people were living, leading to the majority of the towns Roma community fleeing over night leaving behind their homes to be lynched. Roma rights NGO said that gendarmerie were deployed near places where there were Roma houses, but the police had “shown frustration, urging more Gabrovo Roma to spend the next few days with relatives in other municipalities”. Many Roma have never returned as their homes were burned down and their property destroyed.[67]

Czech Republic

Roma make up 2–3% of population in the Czech Republic. According to Říčan (1998), Roma make up more than 60% of Czech prisoners and about 20–30% earn their livelihood in illegal ways, such as procuring prostitution, trafficking and other property crimes.[68] Roma are thus more than 20 times overrepresented in Czech prisons than their population share would suggest.

The Romanis are at the centre of the agenda of far-right groups in the Czech Republic, which spread anti-Romanyism. Among highly publicized cases was the Vítkov arson attack of 2009, in which four right-wing extremists seriously injured a three-year-old Romani girl. The public responded by donating money as well as presents to the family, who were able to buy a new house from the donations, while the perpetrators were sentenced to 18 and 22 years in prison.

According to 2010 survey, 83% of Czechs consider Roma asocial and 45% of Czechs would like to expel them from the Czech Republic.[69] A 2011 poll, which followed after a number of brutal attacks by Romani perpetrators against majority population victims, revealed that 44% of Czechs are afraid of Roma people.[70] The majority of the Czech people do not want to have Romanis as neighbours (almost 90%, more than any other group[71]) seeing them as thieves and social parasites. In spite of long waiting time for a child adoption, Romani children from orphanages are almost never adopted by Czech couples.[72] After the Velvet Revolution in 1989 the jobs traditionally employing Romanis either disappeared or were taken over by immigrant workers.

In January 2010, Amnesty International launched a report titled Injustice Renamed: Discrimination in Education of Roma persists in the Czech Republic.[73] According to the BBC, it was Amnesty's view that while cosmetic changes had been introduced by the authorities, little genuine improvement in addressing discrimination against Romani children has occurred over recent years.[74]

The 2019 Pew Research poll poll found that 66% of Czechs held unfavorable views of Roma.[75]

Denmark

In Denmark, there was much controversy when the city of Helsingør decided to put all Romani students in special classes in its public schools. The classes were later abandoned after it was determined that they were discriminatory, and the Romanis were put back in regular classes.[76]

France

France has come under criticism for its treatment of Roma. In the summer of 2010, French authorities demolished at least 51 illegal Roma camps and began the process of repatriating their residents to their countries of origin.[77] The French government has been accused of perpetrating these actions to pursue its political agenda.[78] In July 2013, Jean-Marie Le Pen, a very controversial far-right politician and founder of the National Front party, had a lawsuit filed against him by the European Roma and Travellers Forum, SOS Racisme and the French Union of Travellers Association after he publicly called France's Roma population "smelly" and "rash-inducing", claiming his comments violated French law on inciting racial hatred.[79]

Germany

After 2005 Germany deported some 50,000 people, mainly Romanis, to Kosovo. They were asylum seekers who fled the country during the Kosovo War. The people were deported after living more than 10 years in Germany. The deportations were highly controversial: many were children and obtained education in Germany, spoke German as their primary language and considered themselves to be Germans.[80]

Hungary

Hungary has seen escalating violence against the Romani people. On 23 February 2009, a Romani man and his five-year-old son were shot dead in Tatárszentgyörgy village southeast of Budapest as they were fleeing their burning house which was set alight by a petrol bomb. The dead man's two other children suffered serious burns. Suspects were arrested and were on trial as of 2011.[81]

In 2012, Viktória Mohácsi, 2004–2009 Hungarian Member of European Parliament of Romani ethnicity, asked for asylum in Canada after previously requesting police protection at home from serious threats she was receiving from hate groups.[82][83]

Italy

In 2007 and 2008, following the brutal rape and subsequent murder of a woman in Rome at the hands of a young man from a local Romani encampment,[84] the Italian government started a crackdown on illegal Roma and Sinti campsites in the country.

In May 2008 Romani camps in Naples were attacked and set on fire by local residents.[85] In July 2008, a high court in Italy overthrew the conviction of defendants who had publicly demanded the expulsion of Romanis from Verona in 2001 and reportedly ruled that "it is acceptable to discriminate against Roma on the grounds that they are thieves".[86] One of those freed was Flavio Tosi, Verona's mayor and an official of the anti-immigrant Lega Nord.[86] The decision came during a "nationwide clampdown" on Romanis by Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi. The previous week, Berlusconi's interior minister Roberto Maroni had declared that all Romanis in Italy, including children, would be fingerprinted.[86]

In 2011 the development of a National Inclusion Strategy Rom Dei Sinti and Caminanti [87] under the supervision of European Commission has defined the presence of Romani camps as an unacceptable condition. As already underlined by many international organizations, the prevalent positioning of the RSC communities in the c.d "nomad camps" fuels segregation and hinders every process of social integration / inclusion; but even where other more stable housing modalities have been found, forms of ghettoization and self-segregation are found, which hinder the process of integration / social inclusion.[88]

Romania

Roma make up 3.3% of population in Romania. Prejudice against Romanis is common amongst the Romanians, who characterize them as thieves, dirty and lazy.[89] A 2000 EU report about Romani said that in Romania... the continued high levels of discrimination are a serious concern...and progress has been limited to programmes aimed at improving access to education.[90] A survey of the Pro Democraţia association in Romania revealed that 94% of the questioned persons believe that the Romanian citizenship should be revoked to the ethnic Romani who commit crimes abroad.[91]

In 2009-2010, a media campaign followed by a parliamentarian initiative asked the Romanian Parliament to accept a proposal to change back the official name of country's Roma (adopted in 2000) to Țigan, the traditional and colloquial Romanian name for Romani, in order to avoid the possible confusion among the international community between the words Roma, which refers to the Romani ethnic minority, and Romania.[92] The Romanian government supported the move on the grounds that many countries in the European Union use a variation of the word Țigan to refer to their Gypsy populations. The Romanian upper house, the Senate, rejected the proposal.[93][94]

Several anti-Romani riots occurred in recent decades, notable of which being the Hădăreni riots of 1993, in which a mob of Romanians and Hungarians, in response to the killing of a Romanian by a Gypsy, burnt down 13 houses belonging to the Gypsies, lynched three Gypsies and forced 130 people to flee the village.[95]

In Baia Mare, Mayor Cătălin Cherecheș announced the building of a 3 metre high, 100 metre long concrete wall to divide the buildings in which the Gypsy community lives from the rest of the city and bring "order and discipline" into the area.[96]

The manele, their modern music style, was prohibited in some cities of Romania in public transport[97] and taxis,[98][99] that action being justified by bus and taxi companies as being for passengers' comfort and a neutral ambience, acceptable for all passengers. However, those actions had been characterised by Speranta Radulescu, a professor of ethno-musicology at the Bucharest Conservatory, as "a defect of Romanian society".[100] There were also a few criticisms of Professor Dr. Ioan Bradu Iamandescu's experimental study, which linked the listening of "manele" to an increased level of aggressiveness and low self-control and suggested a correlation between preference for that music style and low cognitive skills.[101][102]

In 2009, pop singer Madonna defended Romani people during her concert in Bucharest.[103]

Sweden

Roma are one of the five official national minorities in Sweden.[104]

In a survey commissioned by the Equality Ombudsman in 2002/2003, Roma described the discrimination they experience in their daily lives. 90 percent stated that they perceive Sweden to a certain or high degree as a racist country. The same amount agreed to a certain or high degree to the statement that the country has a attitude view towards Roma. 25 percent did neither feel as a part of the Swedish population nor accepted in the Swedish society. And 60 percent said that they have been called derogatory or discriminatory terms related to their ethnic background at least once in the last two years.[105]

Slovakia

According to the last census from 2011, Roma make up 2.0% of the population in Slovakia.

Three Slovakian Romani women have come before the European Court of Human Rights on grounds of having been forcefully sterilised in Slovakian hospitals. The sterilisations were performed by tubal ligation after the women gave birth by Caesarean section. The court awarded two of the women costs and damages while the third case was dismissed because of the woman's death.[106] A report by the Center for Reproductive Rights and the Centre for Civil and Human Rights has compiled more than 100 cases of Roma women in Slovakia who have been sterilised without their informed consent.[107]

Roma are the victims of ethnically driven violence and crime in Slovakia. According to monitoring and reports provided by the European Roma Rights Center (ERRC) in 2013, racist violence, evictions, threats, and more subtle forms of discrimination have increased over the past two years in Slovakia. The ERRC considers the situation in Slovakia to be one of the worst in Europe, as of 2013.[108]

Roma people suffer serious discrimination in Slovakia. Roma children are segregated in school and do not receive the level of education as other Slovakian children. Some are sent to schools for children with mild mental disabilities. As a result, their attainment level is far below average.[109] Amnesty International’s report "Unfulfilled promises: Failing to end segregation of Roma pupils in Slovakia" describes the failure of the Slovak authorities to end the discrimination of Roma children on the grounds of their ethnicity in education. According to a 2012 United Nations Development Programme survey, around 43 per cent of Roma in mainstream schools attended ethnically segregated classes.[110]

Roma people receive new housing from municipalities and regional administrations for free every year, however people complain that some of them end up being destroyed by Roma people themselves.[111][112][113][114] After the destruction, in some cases it has happened that the residents receive new housing, without being criminally prosecuted for destroying state property.[115]

The 2019 Pew Research poll found that 76% of Slovaks held unfavorable views of Roma.[116]

Non-EU countries

Canada

When Romani refugees were allowed into Canada in 1997, a protest was staged by 25 people, including neo-Nazis, in front of the motel where the refugees were staying. The protesters held signs that included, "Honk if you hate Gypsies", "Canada is not a Trash Can", and "G.S.T. – Gypsies Suck Tax". (The last is a reference to Canada's unpopular Goods and Services Tax, also known as GST.) The protesters were charged with promoting hatred, and the case, called R. v. Krymowski, reached the Supreme Court of Canada in 2005.[117]

On 5 September 2012, prominent Canadian conservative commentator Ezra Levant broadcast a commentary "The Jew vs. the Gypsies" on J-Source in which he accused the Romani people of being a group of criminals: "These are gypsies, a culture synonymous with swindlers. The phrase gypsy and cheater have been so interchangeable historically that the word has entered the English language as a verb: he gypped me. Well the gypsies have gypped us. Too many have come here as false refugees. And they come here to gyp us again and rob us blind as they have done in Europe for centuries.… They’re gypsies. And one of the central characteristics of that culture is that their chief economy is theft and begging."[118]

Kosovo

From the end of the Kosovo War in June 1999, about 80% of Kosovo's[a] Romanis were expelled, amounting to approximately 100,000 expellees.[119]:82 For the 1999–2006 period, the European Roma Rights Centre documented numerous crimes perpetrated by Kosovo's ethnic Albanians with the purpose to purge the region of its Romani population along with other non-Albanian ethnic communities. These crimes included murder, abduction and illegal detention, torture, rape, arson, confiscation of houses and other property and forced labour. Whole Romani settlements were burned to the ground by Albanians.[119]:82 Romanis remaining in Kosovo are reported to be systematically denied fundamental human rights. They "live in a state of pervasive fear"[119]:83 and are routinely intimidated, verbally harassed and periodically attacked on racist grounds by Albanians.[119]:83 The Romani community of Kosovo is regarded to be, for the most part, annihilated.[119]:93

At UN internally displaced persons' camps in Kosovska Mitrovica for Romanis, the refugees were exposed to lead poisoning.[120]

Norway

In Norway, many Romani people were forcibly sterilized by the state until 1977.[121][122]

Anti-Romanyism in Norway flared up in July 2012, when roughly 200 Romani people settled outside Sofienberg church in Oslo and were later relocated to a building site at Årvoll, in northern Oslo. The group was subjected to hate crimes in the form of stone throwing and fireworks being aimed at and fired into their camp. They, and Norwegians trying to assist them in their situation, also received death threats.[123] Siv Jensen, the leader of the right-wing Progress Party, also advocated the expulsion of the Romani people resident in Oslo.[124]

Switzerland

A Swiss right-wing magazine, Weltwoche, published a photograph of a gun-wielding Roma child on its cover in 2012, with the title "The Roma are coming: Plundering in Switzerland". They claimed in a series of articles of a growing trend in the country of "criminal tourism for which eastern European Roma clans are responsible", with professional gangs specializing in burglary, thefts, organized begging and street prostitution.[125] The magazine immediately came under criticism for its links to the right-wing populist People's Party (SVP), as being deliberately provocative and encouraged racist stereotyping by linking ethnic origin and criminality.[125] Switzerland's Federal Commission against Racism is considering legal action after complaints in Switzerland, Austria and Germany that the cover breached antiracism laws.

The Berlin newspaper Tagesspiegel investigated the origins of the photograph taken in the slums of Gjakova, Kosovo, where Roma communities were displaced during the Kosovo War to hovels built on a toxic landfill.[126] The Italian photographer, Livio Mancini, denounced the abuse of his photograph, which was originally taken to demonstrate the plight of Roma families in Europe.[127]

New Zealand

The Great Replacement manifesto by Christchurch mosques shooter Brenton Harrison Tarrant described Roma/Gypsies as one of the non-Europeans alongside African, Indian, Turkish, and Semitic (Jewish and Arab) peoples that the shooter wanted to be removed from Europe.[128]

United Kingdom

According to the LGBT rights organisation and charity Stonewall, anti-Romanyism is prevalent in the UK, with a distinction made between Romani people and Irish Travellers (both of whom are commonly known by the exonym "gypsies" in the UK), and the so-called "travellers [and] modern Gypsies".[129] In 2008, the media reported that Gypsies experience a higher degree of racism than any other group in the UK, including asylum-seekers. A Mori poll indicated that a third of UK residents admitted openly to being prejudiced against Gypsies.[130]

Thousands of retrospective planning permissions are granted in Britain in cases involving non-Romani applicants each year, and that statistics showed that 90% of planning applications by Romanis and travellers were initially refused by local councils compared with a national average of 20% for other applicants, disproving claims of preferential treatment favouring Romanis.[131] Travellers argued that the root of the problem was that many traditional stopping places had been barricaded off and that legislation passed by the previous Conservative government had effectively criminalised their community. For example, removing local authorities' responsibility to provide sites leaves the travellers with no option but to purchase unregistered new sites themselves.[132]

In August 2012, Slovakian television network TV JOJ ran a report about cases of Romani immigrant families with Slovakian or Czech citizenship, whose children were forcibly taken away by the British authorities. It has sparked Romani protests in towns such as Nottingham. The authorities refused to explain the reasons for their actions to the Slovak reporters. One of the mothers alleged that she was allowed visitation with her newborn baby only in an empty room; as there was no furniture, she was forced to change her baby's dirty nappies on the floor, which was reflected negatively in a social workers' report. Then, when she would not change the diapers on a subsequent occasion following this experience, failure to change them was reflected negatively in the report as well. TV JOJ also alleged that in another case, a biological mother suffered a nervous breakdown because her children were being taken away, which was seen as proof that she was not able to take care for them and they were then put up for adoption.[133] The problem was further escalated after reports that some Slovak children would be put up for adoption either in the UK or elsewhere, especially after a British court rejected the request of a grandmother, living in Slovakia, for legal custody of her grandchildren.[134] This dispute has sparked protests in front of the British embassy in Bratislava, with protesters holding signs such as "Britain – Thief of Children" and "Stop Legal Kidnappers".[135] According to Slovak media, over 30 Romani children were taken from their parents in Britain. The Slovak government voiced its "serious concern" over the readiness of British authorities to remove children from their "biological parents" for "no sound reason" and further stated its readiness to challenge the policy in front of the European Court of Human Rights.[136]

England

In 2002 Conservative Party politician, and Member of Parliament (MP) for Bracknell Andrew MacKay stated in a House of Commons debate on unauthorised encampments of Gypsies and other Travelling groups in the UK, "They [Gypsies and Travellers] are scum, and I use the word advisedly. People who do what these people have done do not deserve the same human rights as my decent constituents going about their ordinary lives".[137][138] MacKay subsequently left politics in 2010.[139]

In 2005, Doncaster Borough Council discussed in chamber a Review of Gypsy and Traveller Needs[140] and concluded that Gypsies and Irish Travellers are among the most vulnerable and marginalised ethnic minority groups in Britain.[141][142]

A Gypsy and Traveller support centre in Leeds, West Yorkshire, was vandalised in April 2011 in what the police suspect was a hate-crime. The fire caused substantial damage to a centre that is used as a base for the support and education of gypsies and travellers in the community.[143]

Scotland

The Equal Opportunities Committee of the Scottish Parliament in 2001[144] and in 2009[145] confirmed that widespread marginalisation and discrimination persists in Scottish society against gypsy and traveller groups. A 2009 survey conducted by the Scottish Government also concludes that Scottish gypsy and travellers had been largely ignored in official policies. A similar survey in 2006 found discriminatory attitudes in Scotland towards gypsies and travellers,[146] and showed 37 percent of those questioned would be unhappy if a relative married a gypsy or traveller while 48 percent found it unacceptable if a member of the gypsy or traveller minorities became primary school teachers.[146]

A report by the University of the West of Scotland found that both Scottish and UK governments had failed to safeguard the rights of the Roma as a recognized ethnic group and did not raise awareness of Roma rights within the UK.[147] Additionally, an Amnesty International report published in 2012 stated that Gypsy Traveller groups in Scotland routinely suffer widespread discrimination in society,[148] as well as a disproportionate level of scrutiny in the media.[149][150] Over a four-month period as a sample 48 per cent of articles showed Gypsy Travellers in a negative light, while 25–28 per cent of articles were favourable, or of a neutral viewpoint.[148] Amnesty recommended journalists adhere to ethical codes of conduct when reporting on Gypsy Traveller populations in Scotland, as they face fundamental human rights concerns, particularly with regard to health, education, housing, family life and culture.[148]

To tackle the widespread prejudices and needs of Gypsy/Traveller minorities, in 2011, the Scottish Government set up a working party to consider how best to improve community relations between Gypsies/Travellers and Scottish society.[151] Including young Gypsies/Travellers to engage in an on-line positive messages campaign, contain factually correct information on their communities.[152]

Wales

In 2007 a study by the newly formed Equality and Human Rights Commission found that negative attitudes and prejudice persists against Gypsy/Traveller communities in Wales.[153] Results showed that 38 percent of those questioned would not accept a long-term relationship with, or would be unhappy if a close relative married or formed a relationship with, a Gypsy Traveller. Furthermore, only 37 percent found it acceptable if a member of the Gypsy Traveller minorities became primary school teachers, the lowest score of any group.[153] An advertising campaign to tackle prejudice in Wales was launched by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) in 2008.[154]

Northern Ireland

In June 2009, having had their windows broken and deaths threats made against them, 20 Romanian Romani families were forced from their homes in Lisburn Road, Belfast, in Northern Ireland. Up to 115 people, including women and children, were forced to seek refuge in a local church hall after being attacked. They were later moved by the authorities to a safer location.[155] An anti-racist rally in the city on 15 June to support Romani rights was attacked by youths chanting neo-Nazi slogans. The attacks were condemned by Amnesty International[156] and political leaders from both the Unionist and Nationalist traditions in Northern Ireland.[157][158]

Following the arrest of three local youths in relation to the attacks, the church where the Romanis had been given shelter was badly vandalised. Using 'emergency funds', Northern Ireland authorities assisted most of the victims to return to Romania.[159][160]

United States

Elsie Paroubek Affair (1911)

In Chicago in 1911, the highly-publicised disappearance of the five-year old Elsie Paroubek was immediately blamed on "Gypsy child kidnappers". The public was alerted to reports that "Gypsies were seen with a little girl" and many such reports came in. Police raided a "Gypsy" encampment near 18th and South Halstead in Chicago itself and they later expanded the searches and raids to encampments throughout the state of Illinois, to locations as widespread as Round Lake, McHenry, Volo and Cherry Valley - but they found no trace of the missing girl. The police attributed her capture to "the natural love of the wandering people for blue-eyed, yellow-haired children".[161] Lillian Wulff, age 11 - who had actually been kidnapped by some Romanis four years earlier - came forward to offer his assistance, leading the police to conduct further fruitless raids, as well as convincing them to detain the supposed "King of the Gypsies", Elijah George - who, however,"failed to give them the desired information", and was released. Elijah George was detained in Argyle, Wisconsin, and this served to spread the anti-Romani hysteria outside Illinois.

The police finally abandoned this line of investigation. Still, when the girl's body was finally found, her distraught father Frank Paroubek charged: "I am sure the gypsies stole my girl and then when they knew we were after them, they killed her and threw her body into the canal."

Present situation

At the present time, because the Roma population in the United States has quickly assimilated and Roma people are not often portrayed in US popular culture, the term "Gypsy" is typically associated with a trade or lifestyle instead of being associated with the Romani ethnic group. While many Americans consider ethnic costumes offensive (such as blackface), many Americans continue to dress up as gypsy characters for Halloween or other events. Additionally, some small businesses, particularly those in the fortune-telling and psychic reading industry,[162] use the term "Gypsy" to describe themselves or their enterprises, even though they have no ties to the Roma people. Some do, however, as perhaps up to a million Americans, have Romani ancestry (see Romani Americans), but they are usually of partial Romani descent.

While some scholars argue that appropriation of the Roma identity in the United States is based on misconceptions and ignorance rather than anti-Romanyism,[163] Romani advocacy groups decry the practice.[164]

Environmental struggles

Environmental issues which were caused by Cold War-era industrial development have disproportionately impacted the Roma, particularly those Roma who live in Eastern Europe. Most often, the traditional nomadic lifestyle of the Roma causes them to settle on the outskirts of towns and cities, where amenities, employment and educational opportunities are often inaccessible. As of 1993, Hungary has been identified as one country where this issue exists: "While the economic restructuring of a command economy into a western style market economy created hardships for most Hungarians, with the national unemployment rate heading toward 14 percent and per capita real income falling, the burdens which are imposed on Romanis are disproportionately great."[165]

Panel buildings (panelák) in the Chanov ghetto near Most, Czech Republic were built in the 1970s for a high-income clientele, the authorities introduced a model plan, whereby Roma were relocated to these buildings, from poorer areas, to live among Czech neighbors. However, with the rising proportion of Roma moving in, the Czech clients gradually moved out in a kind of white flight, eventually leaving a district in which the vast majority of residents were Roma.[166] A poll in 2007 marked the district as the worst place in the Ústí nad Labem Region.[166] Buildings were eventually stripped of any valuable materials and torn down. The removal of materials was blamed on the Roma who had last inhabited the building.[167] Despite a total rental debt in excess of €3.5 million, all of the tenants in the remaining buildings continue to be provided with water and electricity,[168] unlike the situation in many other European countries.

When newly built in the 1980s, some flats in this settlement were assigned to Roma who had relocated from poverty-stricken locations in a government effort to integrate the Roma population. Other flats were assigned to families of military and law-enforcement personnel. However, the military and police families gradually moved out of the residences and the living conditions for the Roma population deteriorated. Ongoing failures to pay bills led to the disconnection of the water supply and an emergency plan was eventually created to provide running water for two hours per day to mitigate against the bill payment issue. Similarly to Chanov, some of these buildings were stripped of their materials and were eventually torn down; again, the Roma residents were identified as the culprits who were to blame for the theft of the materials.[169][170][171][172]

The various legal hindrances to their traditional nomadic lifestyle have forced many travelling Roma to move into unsafe areas, such as ex-industrial areas, former landfills or other waste areas where pollutants have affected rivers, streams or groundwater. Consequently, Roma are often unable to access clean water or sanitation facilities, rendering the Roma people more vulnerable to health problems, such as diseases. Based in Belgium, the Health & Environment Alliance has included a statement with regard to the Roma on one of its pamphlets: "Denied environmental benefits such as water, sewage treatment facilities, sanitation and access to natural resources, and suffer from exposure to environmental hazards due to their proximity to hazardous waste sites, incinerators, factories, and other sources of pollution."[173] Since the fall of communism and the privatisation of the formerly state owned water-supply companies in many areas of central and eastern Europe, the provision of decent running water to illegal buildings which are often occupied by Roma became a particularly sensitive issue, because the new international owners of the water-supply companies are unwilling to make contracts with the Roma population and as a result, "water-borne diseases, such as diarrhoea and dysentery" became "an almost constant feature of daily life, especially for children".

According to a study that was conducted by the United Nations Development Program, the percentage of Roma with access to running water and sewage treatment within Romania and the Czech Republic is well below the national average in those countries. Consequently, a proliferation of skin diseases among these populations, due to the low quality of housing standards, including scabies, pediculosis, pyoderma, mycosis and ascariasis, has occurred; respiratory health problems also affect the majority of the inhabitants of these areas, in addition to increasing rates of hepatitis and tuberculosis.

Additionally, the permanent settlement of Roma in residential areas is often met with hostility by non-Roma or the exodus of non-Roma, a reaction which is similar to white flight in the United States.[174] Moreover, local councils have issued bans against Roma, who are frequently evicted.

In popular culture

- In "The Big Clan" episode of the television show "Dragnet," originally broadcast on 8 February 1968, Sgt. Friday (Jack Webb) indicates the gypsies are a criminal organization.

- In the 2006 mockumentary Borat, Sacha Baron Cohen's character explains that his home town has "a tall fence for keeping out Gypsies and Jews"; the scene featuring this town was filmed in Glod, a Roma village in central Romania. He makes many more anti-Romani statements throughout the film.

- The Adventures of Tintin comic The Castafiore Emerald criticises anti-Romanyism. After Captain Haddock invites a group of Roma to move onto his property, they are falsely accused of stealing Bianca Castafiore's priceless emerald. Tintin objects to other characters who express their suspicion and uncovers the real culprit to have been a magpie.

- In several adaptations of Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre Dame such as the 1996 Disney version, Claude Frollo is portrayed as having a strong, genocidal hatred of gypsies, although this characteristic is not so evident in the original novel.

- Many instances of Anti-Romanyism are described in Kristian Novak's 2016 novel Ziganin but the most beautiful.[175]

- The 2000 Guy Ritchie crime drama Snatch shows anti-Irish Traveller sentiment among Britons.

See also

- Afrophobia

- À la zingara

- Antisemitism

- Aporophobia

- Caste

- Cultural assimilation

- Discrimination

- Discrimination based on skin color

- Discrimination law

- Environmental racism in Europe

- Hispanophobia

- Human Rights

- Indophobia

- Institutionalized discrimination

- Islamophobia

- List of phobias

- Racial discrimination

- Racism

- Second-class citizen

- Sinophobia

Notes

| a. | ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 97 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 112 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition. |

References

- "Antigypsyism: Reference Paper" (PDF). Antigypsyism.eu. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- White, Karin (1999). "Metal-workers, agriculturists, acrobats, military-people and fortune-tellers: Roma in and around the Byzantine empire". Golden Horn. 7 (2). Archived from the original on 20 March 2001. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- Starr, J. (1936). An Eastern Christian Sect: the Athinganoi. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Trustees for Harvard University, 29, 93-106.

- Bates, Karina. "A Brief History of the Rom". Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- "Book Reviews". Population Studies. 48 (2): 365–372. July 1994. doi:10.1080/0032472031000147856.

- Holler, Martin (2015). "Historical Predecessors of the Term 'Anti-Gypsyism'". Antiziganism: What's in a Word?. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 9781443878715. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- George Soulis (1961): The Gypsies in the Byzantine Empire and the Balkans in the Late Middle Ages (Dumbarton Oaks Papers) Vol.15 pp.146–147, cited in David Crowe (2004): A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia (Palgrave Macmillan) ISBN 0-312-08691-1 p.1

- Achim, Viorel (2004). The Roma in Romanian History. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9639241849.

- David Crowe (2004): A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia (Palgrave Macmillan) ISBN 0-312-08691-1 p.XI

- Crowe (2004) p.2

- Crowe (2004) p.1, p.34

- Crowe (2004) p.34

- Crowe (2004) p.35

- Mayall, David (1995). English gypsies and state policies. f Interface collection Volume 7 of New Saga Library. 7. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. pp. 21, 24. ISBN 978-0-900458-64-4. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Knudsen, Marko D. "The History of the Roma: 2.5.4: 1647 to 1714". Romahistory.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Crowe (2004) p.36-37

- Crowe (2004) p.75

- "Company News Story". Nasdaq.com. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Dillmann, Alfred (1905). Zigeuner-Buch (in German). Munich: Wildsche.

- Congressional Globe, 1st Session, 39th Congress, p. 2891 (1866)

- "Questions: Triangles". The Holocaust History Project. 16 May 2000. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008.

- Headland, Ronald (1992). Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8386-3418-9. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- "Holocaust Encyclopedia – Genocide of European Roma (Gypsies), 1939–1945". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- Hancock, Ian (2005), "True Romanies and the Holocaust: A Re-evaluation and an overview", The Historiography of the Holocaust, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 383–396, ISBN 978-1-4039-9927-6

- Simone Gigliotti, Berel Lang. The Holocaust: a reader. Malden, Massachusetts, USA; Oxford, England, UK; Carlton, Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. Pp. 14.

- Barany, Zoltan D. (2002). The East European gypsies: regime change, marginality, and ethnopolitics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 265–6. ISBN 978-0-521-00910-2.

- Duna, William A. (1985). Gypsies: A Persecuted Race. Duna Studios. Full text in Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, University of Minnesota.

- "Pope Apologizes for Catholic Sins Past and Present". 13 March 2000 – via LA Times.

- "Pope apologises to Roma for Catholic discrimination". BBC News. 2 June 2019 – via www.bbc.com.

- Claire Giangravè (2 June 2019). "Pope apologizes to gypsies for 'discrimination and segregation'". Cruxnow.com. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "Pope Francis asks forgiveness for historical mistreatment of Roma people". CNA.

- Dumitrache, Nicolae; Winfield, Nicole (2 June 2019). "Pope apologizes for history of discrimination against Roma". AP News.

- "Amnesty International – International Roma Day 2011 Stories, Background Information and video material". AI Index: EUR 01/005/2011: Amnesty International. 7 April 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Amnesty International". Web.amnesty.org. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- The Christian Science Monitor (13 February 2008). "Hungary's anti-Roma militia grows". The Christian Science Monitor.

- "roma | Human Rights Press Point". Humanrightspoint.si. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker – Society for Threatened Peoples. "Roma and Ashkali in Kosovo: Persecuted, driven out, poisoned". Gfbv.de. Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "MP publishes inflammatory article against the Roma". bghelsinki.org.

- "IHT.com". IHT.com. 29 March 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Viewpoints by Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights". Coe.int. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Human Rights First Report on Roma". Humanrightsfirst.org. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism — 6. Minority groups". Pew Research Center. 14 October 2019.

- Bona, Marzia (2 August 2018). "How widespread is anti-Roma prejudice?". OBC Transeuropa/EDJNet. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "The Impact of Legislation and Policies on School Segregation of Romani Children". European Roma Rights Centre. 2007. p. 8. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- "Equal access to quality education for Roma, Volume 1" (PDF). Open Society Institute – EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program (EUMAP). 2007. pp. 18–20, 187, 212–213, 358–361. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2007.

- Bagnall, Sam (2 September 2009). "How Gypsy gangs use child thieves". BBC News.

- Miranda Wilson (17 December 2009). "BBC documentary about Roma children sparks outrage". Institute for Race Relations. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- Ivanov, Andrey (December 2002). "7". Avoiding the Dependence Trap: A Regional Human Development Report. United Nations Development Programme. ISBN 92-1-126153-8. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- Denesha, Julie (February 2002). "Anti-Roma racism in Europe". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- "Rromani People: Present Situation in Europe". Union Romani. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- S. Adam Cardais (28 July 2008). "Businessweek.com". Businessweek.com. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Village rallies against Roma influx | Aktuálně.cz". Aktuálně.cz - Víte, co se právě děje. 15 October 2008.

- Traynor, Ian (23 April 2009). "Gypsies suffer widespread racism in European Union". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- "期間工バイブル【バイト・転職求人検索のコペル】". Romadecade.org. Archived from the original on 26 November 2005. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Cowell, Alan (21 February 1995). "Attack on Austrian Gypsies Deepens Fear of Neo-Nazis" – via NYTimes.com.

- "Anti-Roma Protests Escalate - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. 29 September 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Bulgarian rally links Roma to organised crime". BBC News. 1 October 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Изказване на Бойко Борисов в Чикаго – емигрантска версия Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Chicago press conference transcription in Bulgarian

- Chicago audio record Archived 6 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Dead Link)

- Mayor of Sofia brands Roma, Turks and retirees 'bad human material', Telegraph.co.uk, 6 February 2009

- Sofia Mayor to Bulgarian Expats: We Are Left with Bad Human Material Back Home Sofia Mayor to Bulgarian Expats: We Are Left with Bad Human Material Back Home

- Anti-Roma Demonstrations Spread Across Bulgaria, The New York Times

- "България - МВР за протестите за Катуница: Сред най-агресивните бяха 12-13-годишни - Dnevnik.bg". www.dnevnik.bg.

- "Труд". Труд. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Challenge to EPP over leader's statement on bad human material". Socialistgroup.eu. 6 February 2009. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012.

- https://intellinews.com/bulgarian-pm-s-intervention-fails-to-stop-anti-roma-protests-in-gabrovo-159595/

- https://sofiaglobe.com/2019/04/13/many-roma-have-fled-gabrovo-as-bulgarian-town-braces-for-another-no-to-aggression-protest/

- Říčan, Pavel (1998). S Romy žít budeme – jde o to jak: dějiny, současná situace, kořeny problémů, naděje společné budoucnosti. Praha: Portál. pp. 58–63. ISBN 80-7178-250-5.

- Jiří Šťastný (8 February 2012). "Češi propadají anticikánismu, každý druhý tu Romy nechce, zjistil průzkum". Zpravy.idnes.cz. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Romsky bloger nekteri romove se chovaji jako blazni" (in Czech). Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- "Czech don't want Roma as neighbours" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- "What is keeping children in orphanages when so many people want to adopt? – 07-02-2007 – Radio Prague". Radio.cz. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Injustice Renamed: Discrimination in Education of Roma persists in the Czech Republic Amnesty International report, January 2010

- "Amnesty says Czech schools still fail Roma Gypsies". BBC News. 13 January 2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- "European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism — 6. Minority groups". Pew Research Center. 14 October 2019.

- "Roma-politik igen i søgelyset" (in Danish). DR Radio P4. 18 January 2006.

- "France sends Roma Gypsies back to Romania". BBC. 20 August 2010. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "France Begins Controversial Roma Deportations". Der Spiegel. 19 August 2010. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- Gianluca Mezzofiore (18 July 2013). "Jean-Marie Le Pen Sued for Calling Roma Gypsies 'Smelly'". International Business Times. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- "Germany Sending Gypsy Refugees Back to Kosovo". The New York Times. 19 May 2005.

- "Egy megdöbbentő gyilkosságsorozat részletei". Index. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- "Hungarian Roma activist, former member of European Parliament emigrates to Canada". romea.cz.

- "Hungarian MEP to Canada asylum seeker: A Roma's long trek". Politics.hu. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- Hooper, John (2 November 2007). "Italian woman's murder prompts expulsion threat to Romanians". The Guardian. London.

- Unknown, Unknown (28 May 2008). "Italy condemned for 'racism wave'". BBC News. BBC.

- Italy: Court inflames Roma discrimination row The Guardian Retrieved 17 July 2008

- "Strategia Nazionale D'Inclusione Dei Rom, Dei Sinti e Dei Caminanti Attuazione Comunicazione Commissione Europea N.173/2011" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Strategia Nazionale D'Inclusione Dei Rom, Dei Sinti e Dei Caminanti Attuazione Comunicazione Commissione Europea N.173/2011" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. p. 15. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Delia-Luiza Nită, ENAR Shadow Report 2008: Racism in Romania, European Network Against Racism

- "The Situation of Roma in an Enlarged European Union" (PDF). European Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2009.

- Evenimentul Zilei. 7 April 2010. Evz.ro. Retrieved on 2012-01-15.

- "Propunere Jurnalul Naţional". Jurnalul.ro. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Murray, Rupert Wolfe (8 December 2010). "Romania's Government Moves to Rename the Roma". Content.time.com. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Romania Declines to Turn Roma Into 'Gypsies'". Balkaninsight.com. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Hadareni Journal; Death Is a Neighbor, and the Gypsies Are Terrified", in The New York Times, 27 October 1993

- "Roma community segregation still plaguing Romania", Setimes, 18 July 2011

- Corina Misăilă, Vali Trufaşu (28 February 2010). "Primăria de decis: Manelele lui Guţă şi Salam sunt interzise la Galaţi". Stiri din Galati. Adevărul Holding. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "Interzis la manele în taxi!". Liber Tatea (in Romanian). Ringier Romania Toate. 31 March 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Sebastian Dan (14 March 2007). "Fumatul şi manelele, interzise în taxiurile braşovene". Adevărul.ro (in Romanian). Adevărul Holding. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ""Manele", the Most Contested Music of Today". Radio Romania International. 6 February 2012. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- Mariana Minea (10 September 2011). "Prof. dr. Ioan Bradu Iamandescu: "Pe muzică barocă, neuronii capătă un ritm specific geniilor"". Adevărul.ro (in Romanian). Adevărul Holding. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "Cum se comporta creierul cand asculta manele". Stirileprotv.ro (in Romanian). Stirileprotv.ro. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Madonna Booed After Standing Up For Gypsies in Romania

- "National Minorities in Sweden". sweden.se. Swedish Institute. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Diskriminering av Romer i Sverige. Rapport från DO:s projekt åren 2002 och 2003 om åtgärder för att förebygga och motverka etnisk diskriminering av Romer" (PDF). do.se. Ombudsmannen mot etnisk diskriminering. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Kinsella, Naomi. "Forced sterilisation of Roma women is inhuman and degrading but not discriminatory". Hrlc.org.au. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- "Body and Soul: Forced Sterilization and Other Assaults on Roma Reproductive Freedom". Center for Reproductive Rights. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Lake, Aaron (25 December 2013). "The New Roma Ghettos | VICE | United States". Vice.com. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Roma rights". Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- "Slovak authorities in breach of obligations to Romani school children | Amnesty International". Amnesty.org. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "VIDEO Zhorela im bytovka, unimobunky od mesta zničili. Teraz Rómovia nariekajú: Žijeme ako psy!". Pluska.sk (in Slovak). Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "Video: V Trnave búrajú bytovku, ktorú zničili Rómovia". Webnoviny.sk (in Slovak). 2 May 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "Takto si Rómovia zničili bývanie v Žiline". TVnoviny.sk (in Slovak). Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "Rómovia odmietajú ísť do zdevastovaných bytov, ktoré sami zničili". Topky.sk (in Slovak). 17 April 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "Rómovia zničili bytovku, dostali náhradné bývanie". Info.sk (in Slovak). 2 May 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism — 6. Minority groups". Pew Research Center. 14 October 2019.

- R. v. Krymowski [2005] 1 S.C.R. 101.

- "Hate crime investigation launched surrounding Ezra Levant's Roma broadcast". J-Source (website). The Canadian Journalism Foundation. 24 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- Claude Cahn (2007). "Birth of a Nation: Kosovo and the Persecution of Pariah Minorities" (PDF). German Law Journal. 8 (1). ISSN 2071-8322. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2015.

- Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker – Society for Threatened Peoples. "Lead Poisoning of Roma in Idp Camps in Kosovo". Gfbv.de. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Harding, Eleanor (January 2008). "The eternal minority". New Internationalist. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- Hannikainen, Lauri; Åkermark, Sia Spiliopoulou (2003). "The non-autonomous minority groups in the Nordic countries". In Clive, Archer; Joenniemi, Pertti (eds.). The Nordic peace. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 171–197. ISBN 978-0-7546-1417-3.

- "Folk er folk-leder sier han har fått flere drapstrusler". Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- Solvang, Fredrik; Haga Honningsøy, Kirsti (15 July 2012). "Jensen: – Nok er nok, sett opp buss, send dem ut". NRK (in Norwegian). Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Email Us (12 April 2012). "Magazine under fire for racist Roma cover – The Irish Times – Thu, 12 April 2012". The Irish Times. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- von Andrea Dernbach. "Streit um Roma-Reportage: Raubzüge beim Fotografen – Medien – Tagesspiegel" (in German). Tagesspiegel.de. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Anti-Roma front page provokes controversy | Presseurop (English)". Presseurop. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "The Great Replacement" (PDF). 15 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

The invaders must be removed from European soil, regardless whether they came or when they came. Roma, African, Indian, Turkish, Semitic, or other

- Gill Valentine; Ian McDonald. Understanding Prejudice: Attitudes towards minorities (PDF). Stonewall. p. 14. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

They were also criticised in cultural terms for not belonging to a community and allegedly having a negative impact on the environment: for example, they are unsightly, dirty or unhygienic. A clear distinction was also made between Romany Gypsies, respected for their history and culture, and travellers or modern Gypsies.

- Shields, Rachel (6 July 2008). "No blacks, no dogs, no Gypsies". The Independent. London.

- "Gypsies and Irish Travellers: The facts". Commission for Racial Equality. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- "Gypsies". Inside Out – South East. BBC. 19 September 2005.

- "Britské úřady údajně bez příčiny odebírají děti českým a slovenským Romům [British authorities allegedly take away children from Czech and Slovak Romanis without any reason]". novinky.cz (in Czech). novinky.cz. 23 August 2005.

- "Slovak Government Challenges U.K. Foster-Care Ruling". Wall Street Journal. Wall Street Journal. 19 September 2012.

- "Protest pred britskou ambasádou v Bratislave". teraz.sk (in Slovak). teraz.sk. 18 September 2012.

- Booker, Christopher (15 September 2012). "Foreign government may take UK to European court over its 'illegal' child-snatching". Daily Telegraph. London: Daily Telegraph.

- The Gypsy Debate: Can Discourse Control? Joanna Richardson 2006 Imprint academic ch 1 p1.

- Craig, Gary; Karl Atkin; Ronny Flynn; Sangeeta Chattoo (2012). Understanding 'Race' and Ethnicity: Theory, History, Policy, Practice. The Policy Press. p. 153. ISBN 9781847427700.

- "Andrew MacKay Former Conservative MP for Bracknell". They Work For You. mySociety. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "introduction 2.22". Doncaster.gov.uk. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "The Council Chamber". Doncaster.gov.uk. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Gypsies and Travellers: A strategy for the CRE, 2004 – 2007

- Bellamy, Alison (25 April 2011). "Month closure for Leeds traveller arson attack centre". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Clark, Colin (Winter 2006). "Defining Ethnicity in a Cultural and Socio-Legal Context: The Case of Scottish Gypsy-Travellers". Scottish Affairs Scotland's Longest Running Journal on Contemporary Political and Social Issues (54): 39–67. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- "Ethnic Status". The Scottish Government. The Scottish Government. 22 January 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Scottish Government Social Research (4 December 2007). "Attitudes to Discrimination in Scotland 2006: Scottish Social Attitudes Survey – Research Findings". The Scottish Government. The Scottish Government. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Lynne Poole; Kevin Adamson (2008). "Report on the Situation of the Roma Community in Govanhill, Glasgow" (PDF). University of the West of Scotland. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Amnesty International in Scotland; Napier University MSc Journalism (2 April 2012). "Caught in the Headlines – Scottish Media Coverage of Scottish Gypsy Travellers" (PDF). Amnesty International in Scotland. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- "Gypsies/Travellers in Scotland: The Twice Yearly Count – No. 16: July 2009" (PDF). The Scottish Government. The Scottish Government. 30 August 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Beth Cadger (2009). "Gypsy/Traveller Numbers in the UK – A General Overview" (PDF). Article12.org. YGTL – Article 12 in Scotland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- "Working Party Strategy". The Scottish Government. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- "Finance and Sustainable Growth" (PDF). Scottish Parliament – Scottish Executive. Scottish Parliament. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- "Who Do You See? – Living together in Wales" (PDF). Equality and Human Rights Commission. Equality and Human Rights Commission. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Jake Bowers (21 October 2008). "Kirby faces up to anti-Gypsy feeling in Wales". Travellers' Times. The Rural Media Company. Archived from the original (Audio upload and article) on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- "Racist attacks on Roma are latest low in North's intolerant history". irishtimes.com. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- "Amnesty International". Amnesty.org.uk. 17 June 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Morrison, Peter; Lawless, Jill; Selva, Meera; Saad, Nardine; Wolfe Murray, Alina (17 June 2009). "Romanian Gypsies attacked inIreland". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- "Protest held over racist attacks". BBC News. 20 June 2009. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- McDonald, Henry (23 June 2009). "Vandals attack Belfast church that sheltered Romanian victims of racism". guardian.co.uk. London. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- "Romanians leave NI after attacks". BBC News website. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- "Think Gypsies Have His Girl: Father & A Policeman on the Trail of Nomads.", Los Angeles Times, p. I6, 15 April 1911

- "Real Stories From Victims Who've Been Scammed". gypsypsychicscams.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- Sutherland, Anne (1986). Gypsies: The Hidden Americans. Waveland Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-88133-235-3.

- "Breaking 'Gypsy' Stereotypes". Voice of Roma. 23 March 2010.

- Feher, Gyorgy. 1993. Struggling for Ethnic Identity: The Gypsies of Hungary. Library of Congress Card Catalogue: USA.

- Janoušek, Artur (18 September 2007), "Hrůza Ústeckého kraje: sídliště Chanov", IDnes.cz (in Czech), retrieved 13 March 2011

- ČTK (23 June 2006), "V Chanově se bude bourat i druhý vybydlený panelák", Ceskenoviny.cz (in Czech), Czech News Agency, retrieved 13 March 2011

- Slížová, Radka (25 February 2010), "Chanov jde do lepších časů", Sedmicka.cz (in Czech), retrieved 13 March 2011

- Prokop, Dan (28 September 2008). "Košice zbourají "vybydlené" paneláky na romském sídlišti Luník". idnes.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- "LUNÍK IX.: Bývanie na sídlisku je kritické, obyvateľom zriadili konto na pomoc". tvnoviny.sk (in Slovak). 18 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- Teichmanová, Ladislava. "Na Luníku IX a v Demeteri dlhujú za vodu 133 000 €". webnoviny.sk (in Slovak). Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ČTK (5 May 2005). "Na košickém romském sídlišti Luník IX. zase teče voda". romove.radio.cz (in Czech). Archived from the original on 6 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- "Environmental Justice: Listening to Women and Children" (PDF). Environmental Health.

- Krista M. Harper PhD; Tamara Steger, PhD; Richard Filčák, PhD (July 2009). "Environmental Justice and Roma Communities in Central and Eastern Europe" (PDF). University of Massachusetts – Amherst. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Krmpotić, Marinko (1 August 2017). ""Ciganin al' najljepši" Kristijana Novaka: Mračna tema za čitateljsko uživanje / Novi list". Novi list (in Croatian). Retrieved 3 May 2018.