Annexin

Annexin is a common name for a group of cellular proteins. They are mostly found in eukaryotic organisms (animal, plant and fungi).

| Annexin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

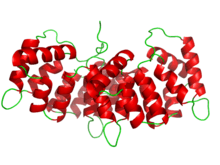

Structure of human annexin III. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Annexin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00191 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001464 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00195 | ||||||||

| SCOPe | 2ran / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| TCDB | 1.A.31 | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 41 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1w3w | ||||||||

| |||||||||

In humans, the annexins are found inside the cell. However some annexins (Annexin A1, Annexin A2, and Annexin A5) have also been found outside the cellular environment, for example, in blood. How the annexins are transported out of the cell into the blood is currently unknown because they lack a signal peptide necessary for proteins to be transported out of the cell.

Annexin is also known as lipocortin.[1] Lipocortins suppress phospholipase A2.[2] Increased expression of the gene coding for annexin-1 is one of the mechanisms by which glucocorticoids (such as cortisol) inhibit inflammation.

Introduction

The protein family of annexins has continued to grow since their association with intracellular membranes was first reported in 1977.[3] The recognition that these proteins were members of a broad family first came from protein sequence comparisons and their cross-reactivity with antibodies.[4] One of these workers (Geisow) coined the name Annexin shortly after.[5]

As of 2002 160 annexin proteins have been identified in 65 different species.[6] The criteria that a protein has to meet to be classified as an annexin are: it has to be capable of binding negatively charged phospholipids in a calcium dependent manner and must contain a 70 amino acid repeat sequence called an annexin repeat. Several proteins consist of annexin with other domains like gelsolin.[7]

The basic structure of an annexin is composed of two major domains. The first is located at the COOH terminal and is called the “core” region. The second is located at the NH2 terminal and is called the “head” region.[6] The core region consists of an alpha helical disk. The convex side of this disk has type 2 calcium-binding sites. They are important for allowing interaction with the phospholipids at the plasma membrane.[8] The N terminal region is located on the concave side of the core region and is important for providing a binding site for cytoplasmic proteins. In some annexins it can become phosphorylated and can cause affinity changes for calcium in the core region or alter cytoplasmic protein interaction.

Annexins are important in various cellular and physiological processes such as providing a membrane scaffold, which is relevant to changes in the cell's shape. Also, annexins have been shown to be involved in trafficking and organization of vesicles, exocytosis, endocytosis and also calcium ion channel formation.[9] Annexins have also been found outside the cell in the extracellular space and have been linked to fibrinolysis, coagulation, inflammation and apoptosis.[10]

The first study to identify annexins was published by Creutz et al. (1978).[11] These authors used bovine adrenal glands and identified a calcium dependent protein that was responsible for aggregation of granules amongst each other and the plasma membrane. This protein was given the name synexin, which comes from the Greek word “synexis” meaning “meeting”.

Structure

Several subfamilies of annexins have been identified based on structural and functional differences. However, all annexins share a common organizational theme that involves two distinct regions, an annexin core and an amino (N)-terminus.[9] The annexin core is highly conserved across the annexin family and the N-terminus varies greatly.[6] The variability of the N-terminus is a physical construct for variation between subfamilies of annexins.

The 310 amino acid annexin core has four annexin repeats, each composed of 5 alpha-helices.[9] The exception is annexin A-VI that has two annexin core domains connected by a flexible linker.[9] A-VI was produced via duplication and fusion of the genes for A-V and A-X and therefore will not be discussed in length. The four annexin repeats produce a curved protein and allow functional differences based on the structure of the curve.[6] The concave side of the annexin core interacts with the N-terminus and cytosolic second messengers, while the convex side of the annexin contains calcium binding sites.[12] Each annexin core contains one type II, also known as an annexin type, calcium binding site; these binding sites are the typical location of ionic membrane interactions.[6] However, other methods of membrane connections are possible. For example, A-V exposes a tryptophan residue, upon calcium binding, which can interact with the hydrocarbon chains of the lipid bilayer.[12]

The diverse structure of the N-terminus confers specificity to annexin intracellular signaling. In all annexins the N-terminus is thought to sit inside the concave side of the annexin core and folds separately from the rest of the protein.[6] The structure of this region can be divided into two broad categories, short and long N-termini. A short N-terminus, as seen in A-III, can consist of 16 or less amino acids and travels along the concave protein core interacting via hydrogen bonds.[9] Short N-termini are thought to stabilize the annexin complex in order to increase calcium binding and can be the sites for post-translational modifications.[9] Long N-termini can contain up to 40 residues and have a more complex role in annexin signaling.[6] For example, in A-I the N-terminus folds into an amphipathic alpha-helix and inserts into the protein core, displacing helix D of annexin repeat III.[6] However, when calcium binds, the N-terminus is pushed from the annexin core by conformational changes within the protein.[9] Therefore, the N-terminus can interact with other proteins, notably the S-100 protein family, and includes phosphorylation sites which allow for further signaling.[9] A-II can also use its long N-terminal to form a heterotrimer between a S100 protein and two peripheral annexins.[9] The structural diversity of annexins is the grounds for the functional range of these complex, intracellular messengers.

Cellular localization

Membrane

Annexins are characterized by their calcium dependent ability to bind to negatively charged phospholipids (i.e. membrane walls).[13] They are located in some but not all of the membranous surfaces within a cell, which would be evidence of a heterogeneous distribution of Ca2+ within the cell.[9]

Nuclei

Annexin species (II,V,XI) have been found within the membranes.[9] Tyrosine kinase activity has been shown to increase the concentrations of Annexins II,V within the nucleus.[9] Annexin XI is predominantly located within the nucleus, and absent from the nucleoli.[14] During prophase, annexin XI will translocate to the nuclear envelope.[14]

Bone

Annexins are abundant in bone matrix vesicles, and are speculated to play a role in Ca2+ entry into vesicles during hydroxyapatite formation.[15] The subject area has not been thoroughly studied, however it has been speculated that annexins may be involved in closing the neck of the matrix vesicle as it is endocytosed.[9]

Role in vesicle transport

Exocytosis

Annexins have been observed to play a role along the exocytotic pathway, specifically in the later stages, near or at the plasma membrane.[13] Evidence of annexins or annexin-like proteins are involved in exocytosis has been found in lower organisms, such as the Paramecium.[13] Through antibody recognition, there is evidence of the annexin like proteins being involved in the positioning and attachment of secretory organelles in the organism Paramecium.[13]

Annexin VII was the first annexin to be discovered while searching for proteins that promote the contact and fusion of chromaffin granules.[9] In Vitro studies however have shown that annexin VII does not promote the fusion of membranes, only the close attachment to one another.[11]

Endocytosis

Annexins have been found to be involved in the transport and also sorting of endocytotic events. Annexin one is a substrate of the EGF (epidermal growth factor) tyrosine kinase which becomes phosphorylated on its N terminus when the receptor is internalized.[13] Unique endosome targeting sequences have been found in the N terminus of annexins I and II, which would be useful in sorting of endocytotic vesicles.[9] Annexins are present in several different endocytotic processes. Annexin VI is thought to be involved in clathrin coated budding events, while annexin II participates in both cholesteryl ester internalization and the biogenesis of multi-vesicular endosomes.[9]

Membrane scaffolding

Annexins can function as scaffolding proteins to anchor other proteins to the cell membrane. Annexins assemble as trimers,[8] where this trimer formation is facilitated by calcium influx and efficient membrane binding. This trimer assembly is often stabilized by other membrane-bound annexin cores in the vicinity. Eventually, enough annexin trimers will assemble and bind the cell membrane. This will induce the formation of membrane-bound annexin networks. These networks can induce the indentation and vesicle budding during an exocytosis event.[16]

While different types of annexins can function as membrane scaffolds, annexin A-V is the most abundant membrane-bound annexin scaffold. Annexin A-V can form 2-dimensional networks when bound to the phosphatidylserine unit of the membrane.[17] Annexin A-V is effective in stabilizing changes in cell shape during endocytosis and exocytosis, as well as other cell membrane processes. Alternatively, annexins A-I and A-II bind phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylcholine units in the cell membrane, and are often found forming monolayered clusters that lack a definite shape.[18]

In addition, annexins A-I and A-II have been shown to bind PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate) in the cell membrane and facilitate actin assembly near the membrane.[9] More recently, annexin scaffolding functions have been linked to medical applications. These medical implications have been uncovered with in vivo studies where the path of a fertilized egg is tracked to the uterus. After fertilization, the egg must enter a canal for which the opening is up to five times smaller than the diameter of the egg. Once the fertilized egg has passed through the opening, annexins are believed to promote membrane folding in an accordion-like fashion to return the stretched membrane back to its original form. Though this was discovered in the nematode annexin NEX-1, it is believed that a similar mechanism takes place in humans and other mammals.[19]

Membrane organization and trafficking

Several annexins have been shown to have active roles in the organization of the membrane. Annexin A-II has been extensively studied in this aspect of annexin function and is noted to be heavily involved in the organization of lipids in the bilayer near sites of actin cytoskeleton assembly. Annexin A-II can bind PIP2 in the cell membrane in vivo with a relatively high binding affinity.[20]

In addition, Annexin A-II can bind other membrane lipids such as cholesterol, where this binding is made possible by the influx of calcium ions.[21] The binding of Annexin A-II to lipids in the bilayer orchestrates the organization of lipid rafts in the bilayer at sites of actin assembly. In fact, annexin A-II is itself an actin-binding protein and therefore it can form a region of interaction with actin by means of its filamentous actin properties. In turn, this allows for further cell-cell interactions between monolayers of cells like epithelial and endothelial cells.[22] In addition to annexin A-II, annexin A-XI has also been shown to organize cell membrane properties. Annexin A-XI is believed to be highly involved in the last stage of mitosis: cytokinesis. It is in this stage that daughter cells separate from one another because annexin A-XI inserts a new membrane that is believed to be required for abscission. Without annexin A-XI, it is believed that the daughter cells with not fully separate and may undergo apoptosis.[23]

Clinical significance

Apoptosis and inflammation

Annexin A-I seems to be one of the most heavily involved annexins in anti-inflammatory responses. Upon infection or damage to tissues, annexin A-I is believed to reduce inflammation of tissues by interacting with annexin A-I receptors on leukocytes. In turn, the activation of these receptors functions to send the leukocytes to the site of infection and target the source of inflammation directly.[24] As a result, this inhibits leukocyte (specifically neutrophils) extravasation and down regulates the magnitude of the inflammatory response. Without annexin A-I in mediating this response, neutrophil extravasation is highly active and worsens the inflammatory response in damaged or infected tissues.[25]

Annexin A-I has also been implicated in apoptotic mechanisms in the cell. When expressed on the surface of neutrophils, annexin A-I promotes pro-apoptotic mechanisms. Alternatively, when expressed on the cell surface, annexin A-I promotes the removal of cells that have undergone apoptosis.[26] [27]

Moreover, annexin A-I has further medical implications in the treatment of cancer. Annexin A-I can be used as a cell surface protein to mark some forms of tumors that can be targeted by various immunotherapies with antibodies against annexin A-I.[28]

Coagulation

Annexin A-V is the major player when it comes to mechanisms of coagulation. Like other annexin types, annexin A-V can also be expressed on the cell surface and can function to form 2-dimensional crystals to protect the lipids of the cell membrane from involvement in coagulation mechanisms.[9] Medically speaking, phospholipids can often be recruited in autoimmune responses, most commonly observed in cases of fetal loss during pregnancy. In such cases, antibodies against annexin A-V destroy its 2-dimensional crystal structure and uncover the phospholipids in the membrane, making them available for contribution to various coagulation mechanisms.[29]

Fibrinolysis

While several annexins may be involved in mechanisms of fibrinolysis, annexin A-II is the most prominent in mediating these responses. The expression of annexin A-II on the cell surface is believed to serve as a receptor for plasminogen, which functions to produce plasmin. Plasmin initiates fibrinolysis by degrading fibrin. The destruction of fibrin is a natural preventative measure because it prevents the formation of blood clots by fibrin networks.[30]

Annexin A-II has medical implications because it can be utilized in treatments for various cardiovascular diseases that thrive on blood clotting through fibrin networks.

Types/subfamilies

- Annexin, type I InterPro: IPR002388

- Annexin, type II InterPro: IPR002389

- Annexin, type III InterPro: IPR002390

- Annexin, type IV InterPro: IPR002391

- Annexin, type V InterPro: IPR002392

- Annexin, type VI InterPro: IPR002393

- Alpha giardin InterPro: IPR008088

- Annexin, type X InterPro: IPR008156

- Annexin, type VIII InterPro: IPR009115

- Annexin, type XXXI InterPro: IPR009116

- Annexin, type fungal XIV InterPro: IPR009117

- Annexin, type plant InterPro: IPR009118

- Annexin, type XIII InterPro: IPR009166

- Annexin, type VII InterPro: IPR013286

- Annexin like protein InterPro: IPR015472

- Annexin XI InterPro: IPR015475

Human proteins containing this domain

ANXA1; ANXA10; ANXA11; ANXA13; ANXA2; ANXA3; ANXA4; ANXA5; ANXA6; ANXA7; ANXA8; ANXA8L1; ANXA8L2; ANXA9;

References

- Annexins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- lipocortin definition

- Donnelly SR, Moss SE (June 1997). "Annexins in the secretory pathway". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 53 (6): 533–8. doi:10.1007/s000180050068. PMID 9230932.

- Geisow MJ, Fritsche U, Hexham JM, Dash B, Johnson T (April 1986). "A consensus sequence repeat in Torpedo and mammalian calcium-dependent membrane binding proteins". Nature. 320 (6063): 636–38. doi:10.1038/320636a0. PMID 2422556.

- Geisow MJ, Walker JH, Boustead C, Taylor W (April 1987). "Annexins – a new family of Ca2+ -regulated phospholipid-binding protein". Biosci. Rep. 7 (4): 289–98. doi:10.1007/BF01121450. PMID 2960386.

- Gerke V, Moss S (2002). "Annexins: form structure to function". Physiol. Rev. 82 (2): 331–71. doi:10.1152/physrev.00030.2001. PMID 11917092.

- Ghoshdastider, U; Popp, D; Burtnick, L. D.; Robinson, R. C. (2013). "The expanding superfamily of gelsolin homology domain proteins". Cytoskeleton. 70 (11): 775–95. doi:10.1002/cm.21149. PMID 24155256.

- Oling F, Santos JS, Govorukhina N, Mazères-Dubut C, Bergsma-Schutter W, Oostergetel G, Keegstra W, Lambert O, Lewit-Bentley A, Brisson A (December 2000). "Structure of membrane-bound annexin A5 trimers: a hybrid cryo-EM – X-ray crystallography study". J. Mol. Biol. 304 (4): 561–73. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.4183. PMID 11099380.

- Gerke V, Creutz CE, Moss SE (June 2005). "Annexins: linking Ca2+ signalling to membrane dynamics". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 (6): 449–61. doi:10.1038/nrm1661. PMID 15928709.

- van Genderen HO, Kenis H, Hofstra L, Narula J, Reutelingsperger CP (June 2008). "Extracellular annexin A5: functions of phosphatidylserine-binding and two-dimensional crystallization". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1783 (6): 953–63. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.030. PMID 18334229.

- Creutz Carl E.; Pazoles Christopher J.; Pollard Harvey B. (April 1978). "Identification and purification of an adrenal medullary protein (synexin) that causes calcium-dependent aggregation of isolated chromaffin granules". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 253 (8): 2858–66. PMID 632306.

- Concha NO, Head JF, Kaetzel MA, Dedman JR, Seaton BA (September 1993). "Rat annexin V crystal structure: Ca(2+)-induced conformational changes". Science. 261 (5126): 1321–4. doi:10.1126/science.8362244. PMID 8362244.

- Gerke V, Moss SE (June 1997). "Annexins and membrane dynamics". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1357 (2): 129–54. doi:10.1016/S0167-4889(97)00038-4. PMID 9223619.

- Tomas A, Moss S (2003). "Calcium- and Cell Cycle-dependent Association of Annexin 11 with the Nuclear Envelope". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (22): 20210–20216. doi:10.1074/jbc.M212669200. PMID 12601007.

- Genge BR, Wu LN, Wuthier RE (March 1990). "Differential fractionation of matrix vesicle proteins. Further characterization of the acidic phospholipid-dependent Ca2+–binding proteins". J. Biol. Chem. 265 (8): 4703–10. PMID 2155235.

- Kenis H, van Genderen H, Bennaghmouch A, Rinia HA, Frederik P, Narula J, Hofstra L, Reutelingsperger CP (December 2004). "Cell surface-expressed phosphatidylserine and annexin A5 open a novel portal of cell entry". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (50): 52623–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M409009200. PMID 15381697.

- Pigault C, Follenius-Wund A, Schmutz M, Freyssinet JM, Brisson A (February 1994). "Formation of two-dimensional arrays of annexin V on phosphatidylserine-containing liposomes". J. Mol. Biol. 236 (1): 199–208. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1129. PMID 8107105.

- Janshoff A, Ross M, Gerke V, Steinem C (August 2001). "Visualization of annexin I binding to calcium-induced phosphatidylserine domains". ChemBioChem. 2 (7–8): 587–90. doi:10.1002/1439-7633(20010803)2:7/8<587::AID-CBIC587>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 11828493.

- Creutz CE, Snyder SL, Daigle SN, Redick J (March 1996). "Identification, localization, and functional implications of an abundant nematode annexin". J. Cell Biol. 132 (6): 1079–92. doi:10.1083/jcb.132.6.1079. PMC 2120750. PMID 8601586.

- Rescher U, Ruhe D, Ludwig C, Zobiack N, Gerke V (July 2004). "Annexin 2 is a phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate binding protein recruited to actin assembly sites at cellular membranes". J. Cell Sci. 117 (Pt 16): 3473–80. doi:10.1242/jcs.01208. PMID 15226372.

- Rescher U, Gerke V (June 2004). "Annexins--unique membrane binding proteins with diverse functions". J. Cell Sci. 117 (Pt 13): 2631–9. doi:10.1242/jcs.01245. PMID 15169834.

- Hayes MJ, Rescher U, Gerke V, Moss SE (August 2004). "Annexin-actin interactions". Traffic. 5 (8): 571–6. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00210.x. PMID 15260827.

- Tomas A, Futter C, Moss SE (2004). "Annexin 11 is required for midbody formation and completion of the terminal phase of cytokinesis". J. Cell Biol. 165 (6): 813–822. doi:10.1083/jcb.200311054. PMC 2172404. PMID 15197175.

- Prossnitz ER, Ye RD (1997). "The N-formyl peptide receptor: a model for the study of chemoattractant receptor structure and function". Pharmacol. Ther. 74 (1): 73–102. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(96)00203-3. PMID 9336017.

- Hannon R, Croxtall JD, Getting SJ, Roviezzo F, Yona S, Paul-Clark MJ, Gavins FN, Perretti M, Morris JF, Buckingham JC, Flower RJ (February 2003). "Aberrant inflammation and resistance to glucocorticoids in annexin 1-/- mouse". FASEB J. 17 (2): 253–5. doi:10.1096/fj.02-0239fje. PMID 12475898.

- Arur S, Uche UE, Rezaul K, Fong M, Scranton V, Cowan AE, Mohler W, Han DK (April 2003). "Annexin I is an endogenous ligand that mediates apoptotic cell engulfment". Dev. Cell. 4 (4): 587–98. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00090-X. PMID 12689596.

- Arur, S.; et al. (2003). "Annexin I is an endogenous ligand that mediates apoptotic cell engulfment". Dev. Cell. 4 (4): 587–598. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00090-X. PMID 12689596.

- Oh P, Li Y, Yu J, Durr E, Krasinska KM, Carver LA, Testa JE, Schnitzer JE (June 2004). "Subtractive proteomic mapping of the endothelial surface in lung and solid tumours for tissue-specific therapy". Nature. 429 (6992): 629–35. doi:10.1038/nature02580. PMID 15190345.

- Rand JH (September 2000). "Antiphospholipid antibody-mediated disruption of the annexin-V antithrombotic shield: a thrombogenic mechanism for the antiphospholipid syndrome". J. Autoimmun. 15 (2): 107–11. doi:10.1006/jaut.2000.0410. PMID 10968894.

- Ling Q, Jacovina AT, Deora A, Febbraio M, Simantov R, Silverstein RL, Hempstead B, Mark WH, Hajjar KA (January 2004). "Annexin II regulates fibrin homeostasis and neoangiogenesis in vivo". J. Clin. Invest. 113 (1): 38–48. doi:10.1172/JCI19684. PMC 300771. PMID 14702107.

Further reading

- Bauer B, Engelbrecht S, Bakker-Grunwald T, Scholze H (April 1999). "Functional identification of alpha 1-giardin as an annexin of Giardia lamblia". FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 173 (1): 147–53. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(99)00064-6. PMID 10220891.

- Moss SE, Morgan RO (2004). "The annexins". Genome Biol. 5 (4): 219. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-4-219. PMC 395778. PMID 15059252.

External links

- European Annexin Homepage, acquired on 20 August 2005

- UMich Orientation of Proteins in Membranes families/superfamily-43 - Calculated spatial positions of annexins in membranes (the initially bound state)

- Annexins repeated domain in PROSITE