Zambia

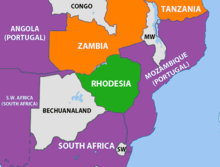

Zambia (/ˈzæmbiə, ˈzɑːm-/), officially the Republic of Zambia (Tonga: Cisi ca Zambia; Nyanja: Dziko la Zambia), is a landlocked country in Southern-Central Africa[10] (although some sources consider it part of East Africa[11]). Its neighbours are the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the north-east, Malawi to the east, Mozambique to the southeast, Zimbabwe and Botswana to the south, Namibia to the southwest, and Angola to the west. The capital city is Lusaka, located in the south-central part of Zambia. The population is concentrated mainly around Lusaka in the south and the Copperbelt Province to the northwest, the core economic hubs of the country.

Republic of Zambia | |

|---|---|

Motto: "One Zambia, One Nation" | |

.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city | Lusaka 15°25′S 28°17′E |

| Official languages | English |

| Recognised regional languages | |

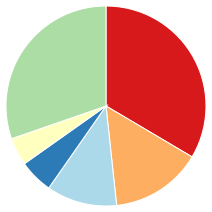

| Ethnic groups (2010[1]) | List

|

| Religion (2010)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Zambian |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

• President | Edgar Lungu |

• Vice President | Inonge Wina |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| History | |

| 27 June 1890 | |

| 28 November 1899 | |

| 29 January 1900 | |

| 17 August 1911 | |

| 1 August 1953 | |

| 24 October 1964 | |

| 5 January 2016 | |

• Established | 1964 |

| Area | |

• Total | 752,618 km2 (290,587 sq mi)[3] (38th) |

• Water (%) | 1 |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 17,351,708[4][5] (65th) |

| 13,092,666[6] | |

• Density | 17.2/km2 (44.5/sq mi) (191st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $250.52 billion[7] |

• Per capita | $7,180[7] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $120.137 billion[7] |

• Per capita | $3,342[7] |

| Gini (2015) | 57.1[8] high |

| HDI (2018) | medium · 143rd |

| Currency | Zambian kwacha (ZMW) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +260 |

| ISO 3166 code | ZM |

| Internet TLD | .zm |

Originally inhabited by Khoisan peoples, the region was affected by the Bantu expansion of the thirteenth century. Following European explorers in the eighteenth century, the British colonised the region into the British protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesia towards the end of the nineteenth century. These were merged in 1911 to form Northern Rhodesia. For most of the colonial period, Zambia was governed by an administration appointed from London with the advice of the British South Africa Company.[12]

On 24 October 1964, Zambia became independent of the United Kingdom and prime minister Kenneth Kaunda became the inaugural president. Kaunda's socialist United National Independence Party (UNIP) maintained power from 1964 until 1991. Kaunda played a key role in regional diplomacy, cooperating closely with the United States in search of solutions to conflicts in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Angola, and Namibia.[13] From 1972 to 1991 Zambia was a one-party state with the UNIP as the sole legal political party under the motto "One Zambia, One Nation". Kaunda was succeeded by Frederick Chiluba of the social-democratic Movement for Multi-Party Democracy in 1991, beginning a period of social-economic growth and government decentralisation. Levy Mwanawasa, Chiluba's chosen successor, presided over Zambia from January 2002 until his death on 19th August 2008 and is credited with campaigns to reduce corruption and increase the standard of living. After Mwanawasa's death, Rupiah Banda presided as Acting President before being elected President in 2008. Holding the office for only three years, Banda stepped down after his defeat in the 2011 elections by Patriotic Front party leader Michael Sata. Sata died on 28 October 2014, making him the second Zambian president to die in office.[14] Guy Scott served briefly as interim president until new elections were held on 20 January 2015,[15] in which Edgar Lungu was elected as the sixth President.

Zambia contains vast amounts of natural resources such as minerals, wildlife, forestry, freshwater and arable land.[16]In 2010, the World Bank named Zambia one of the world's fastest economically reformed countries.[17] The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) is headquartered in Lusaka.

Etymology

The territory of what is now Zambia was known as Northern Rhodesia from 1911. It was renamed Zambia at independence in 1964. The new name of Zambia was derived from the Zambezi river (Zambezi may mean "Grand River").[18]

History

Prehistoric era

The area of modern Zambia is known to have been inhabited by the Khoisan until around AD 300, when migrating Bantu began to settle around these areas.[19] These early hunter-gatherer groups were later either annihilated or absorbed by subsequent more organised Bantu groups.

Archaeological excavation work on the Zambezi Valley and Kalambo Falls show a succession of human cultures. In particular, ancient camping site tools near the Kalambo Falls have been radiocarbon dated to more than 36,000 years ago.

The fossil skull remains of Broken Hill Man, dated between 300,000 and 125,000 years BC, further shows that the area was inhabited by early humans.[20]

Bantu empires

The early history of the peoples of modern Zambia can only be gleaned from knowledge passed down by generations through word of mouth.[21]

In the 12th century, waves of Bantu-speaking immigrants arrived during the Bantu expansion. Among them, the Tonga people (also called Ba-Tonga, "Ba-" meaning "men") were the first to settle in Zambia and are believed to have come from the east near the "big sea". The Nkoya people also arrived early in the expansion, coming from the Luba–Lunda kingdoms in the southern parts of the modern Democratic Republic of the Congo and northern Angola, followed by a much larger influx, especially between the late 12th and early 13th centuries[22]

To the east, the Maravi Empire, also spanning the vast areas of Malawi and parts of modern northern Mozambique began to flourish under Kalonga.

At the end of the 18th century, some of the Mbunda migrated to Barotseland, Mongu upon the migration of among others, the Ciyengele.[23][24] The Aluyi and their leader, the Litunga Mulambwa, especially valued the Mbunda for their fighting ability.

In the early 19th century, the Nsokolo people settled in the Mbala district of Northern Province. During the 19th century, the Ngoni and Sotho peoples arrived from the south. By the late 19th century, most of the various peoples of Zambia were established in their current areas.

European contact

The earliest recorded European to visit the area was the Portuguese explorer Francisco de Lacerda in the late 18th century. Lacerda led an expedition from Mozambique to the Kazembe region in Zambia (with the goal of exploring and to crossing Southern Africa from coast to coast for the first time),[25] and died during the expedition in 1798. The expedition was from then on led by his friend Francisco Pinto.[26] This territory, located between Portuguese Mozambique and Portuguese Angola, was claimed and explored by Portugal in that period.

Other European visitors followed in the 19th century. The most prominent of these was David Livingstone, who had a vision of ending the slave trade through the "3 Cs": Christianity, Commerce, and Civilisation. He was the first European to see the magnificent waterfalls on the Zambezi River in 1855, naming them the Victoria Falls after Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. He described them thus: "Scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight".[27]

Locally the falls are known as "Mosi-o-Tunya" or "thundering smoke" in the Lozi or Kololo dialect. The town of Livingstone, near the Falls, is named after him. Highly publicised accounts of his journeys motivated a wave of European visitors, missionaries and traders after his death in 1873.[28]

British South Africa Company

In 1888, the British South Africa Company (BSA Company), led by Cecil Rhodes, obtained mineral rights from the Litunga of the Lozi people, the Paramount Chief of the Lozi (Ba-rotse) for the area which later became Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia.[29]

To the east, in December 1897 a group of the Angoni or Ngoni (originally from Zululand) rebelled under Tsinco, son of King Mpezeni, but the rebellion was put down,[30] and Mpezeni accepted the Pax Britannica. That part of the country then came to be known as North-Eastern Rhodesia. In 1895, Rhodes asked his American scout Frederick Russell Burnham to look for minerals and ways to improve river navigation in the region, and it was during this trek that Burnham discovered major copper deposits along the Kafue River.[31]

North-Eastern Rhodesia and Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia were administered as separate units until 1911 when they were merged to form Northern Rhodesia, a British protectorate. In 1923, the BSA Company ceded control of Northern Rhodesia to the British Government after the government decided not to renew the Company's charter.

British colonisation

In 1923, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), a conquered territory which was also administered by the BSA Company, became a self-governing British colony. In 1924, after negotiations, the administration of Northern Rhodesia transferred to the British Colonial Office.

Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

In 1953, the creation of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland grouped together Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland (now Malawi) as a single semi-autonomous region. This was undertaken despite opposition from a sizeable minority of the population, who demonstrated against it in 1960–61.[32] Northern Rhodesia was the center of much of the turmoil and crisis characterizing the federation in its last years. Initially, Harry Nkumbula's African National Congress (ANC) led the campaign, which Kenneth Kaunda's United National Independence Party (UNIP) subsequently took up.

Independence

A two-stage election held in October and December 1962 resulted in an African majority in the legislative council and an uneasy coalition between the two African nationalist parties. The council passed resolutions calling for Northern Rhodesia's secession from the federation and demanding full internal self-government under a new constitution and a new National Assembly based on a broader, more democratic franchise.[33]

The federation was dissolved on 31 December 1963, and in January 1964, Kaunda won the only election for Prime Minister of Northern Rhodesia. The Colonial Governor, Sir Evelyn Hone, was very close to Kaunda and urged him to stand for the post. Soon after, there was an uprising in the north of the country known as the Lumpa Uprising led by Alice Lenshina – Kaunda's first internal conflict as leader of the nation.[34]

Northern Rhodesia became the Republic of Zambia on 24 October 1964, with Kenneth Kaunda as the first president. At independence, despite its considerable mineral wealth, Zambia faced major challenges. Domestically, there were few trained and educated Zambians capable of running the government, and the economy was largely dependent on foreign expertise. This expertise was provided in part by John Willson CMG[35] There were over 70,000 Europeans resident in Zambia in 1964, and they remained of disproportionate economic significance.[36]

Tensions with neighbours

Kaunda's endorsement of Patriotic Front guerrillas conducting raids into neighbouring (Southern) Rhodesia resulted in political tension and a militarisation of the border, leading to its closure in 1973.[37] The Kariba hydroelectric station on the Zambezi River provided sufficient capacity to satisfy the country's requirements for electricity, despite Rhodesian management.

On 3 September 1978, civilian airliner, Air Rhodesia Flight 825, was shot down near Kariba by the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA). 18 people, including children, survived the crash only for most of them to be shot by militants of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) led by Joshua Nkomo. Rhodesia responded with Operation Gatling, an attack on Nkomo's guerilla bases in Zambia, in particular, his military headquarters just outside Lusaka; this raid became known as the Green Leader Raid. On the same day, two more bases in Zambia were attacked using air power and elite paratroops and helicopter-borne troops.[38]

A railway (TAZARA – Tanzania Zambia Railways) to the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam, completed in 1975 with Chinese assistance, reduced Zambian dependence on railway lines south to South Africa and west through an increasingly troubled Portuguese Angola. Until the completion of the railway, Zambia's major artery for imports and the critical export of copper was along the TanZam Road, running from Zambia to the port cities in Tanzania. The Tazama oil pipeline was also built from Dar es Salaam to Ndola in Zambia.

By the late 1970s, Mozambique and Angola had attained independence from Portugal. Rhodesia's predominantly white government, which issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965, accepted majority rule under the Lancaster House Agreement in 1979.[39]

Civil strife in both Portuguese colonies and a mounting Namibian War of Independence resulted in an influx of refugees[40] and compounded transportation issues. The Benguela railway, which extended west through Angola, was essentially closed to Zambian traffic by the late 1970s. Zambia's support for anti-apartheid movements such as the African National Congress (ANC) also created security problems as the South African Defence Force struck at dissident targets during external raids.[41]

Economic troubles

In the mid-1970s, the price of copper, Zambia's principal export, suffered a severe decline worldwide. In Zambia's situation, the cost of transporting the copper great distances to the market was an additional strain. Zambia turned to foreign and international lenders for relief, but, as copper prices remained depressed, it became increasingly difficult to service its growing debt. By the mid-1990s, despite limited debt relief, Zambia's per capita foreign debt remained among the highest in the world.[42][43]

Democratisation

In June 1990 riots against Kaunda accelerated. Many protesters were killed by the regime in breakthrough June 1990 protests.[44][45] In 1990 Kaunda survived an attempted coup, and in 1991 he agreed to reinstate multiparty democracy, having instituted one-party rule under the Choma Commission of 1972. Following multiparty elections, Kaunda was removed from office (see below).

In the 2000s, the economy stabilised, attaining single-digit inflation in 2006–2007, real GDP growth, decreasing interest rates, and increasing levels of trade. Much of its growth is due to foreign investment in mining and to higher world copper prices. All this led to Zambia being courted enthusiastically by aid donors and saw a surge in investor confidence in the country.

Politics

Politics in Zambia take place in a framework of a presidential representative democratic republic, whereby the President of Zambia is both head of state and head of government in a pluriform multi-party system. The government exercises executive power, while legislative power is vested in both the government and parliament.

Zambia became a republic immediately upon attaining independence in October 1964. From 2011 to 2014, Zambia's president had been Michael Sata, until Sata died on 28 October 2014.[46]

After Sata's death, Vice President Guy Scott, a Zambian of Scottish descent, became acting President of Zambia. On 24 January 2015, it was announced that Edgar Chagwa Lungu had won the election to become the 6th President in a tightly contested race. He won 48.33% of the vote, a lead of 1.66% over his closest rival, Hakainde Hichilema, with 46.67%.[47] 9 other candidates all got less than 1% each.

Foreign relations

.jpg)

After independence in 1964, the foreign relations of Zambia were mostly focused on supporting liberation movements in other countries in Southern Africa, such as the African National Congress and SWAPO. During the Cold War, Zambia was a member of the Non-Aligned Movement.

Military

The Zambian Defence Force (ZDF) consists of the Zambia Army (ZA), the Zambia Air Force (ZAF), and the Zambian National Service (ZNS). The ZDF is designed primarily against external threats.

In 2019, Zambia signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[48]

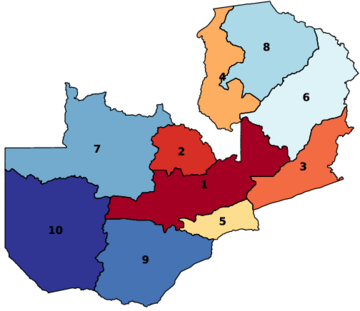

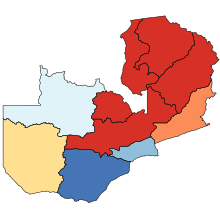

Administrative divisions

Zambia is divided into ten provinces, which are further divided into 117 districts, 156 constituencies and 1,281 wards.

- Provinces

Human rights

The government is sensitive to the opposition and other criticism and has been quick to prosecute critics using the legal pretext that they had incited public disorder. Libel laws are used to suppress free speech and the press.[49]

Same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both males and females in Zambia.[50][51] A 2010 survey revealed that only 2% of Zambians find homosexuality to be morally acceptable.[52]

In December 2019, it was reported that United States Ambassador to Zambia Daniel Lewis Foote was "horrified" by Zambia's jailing of same-sex couple Japhet Chataba and Steven Samba. After an appeal failed and the couple was sentenced to 15 years in prison, Foote asked the Zambian government to review both the case and the country's anti-homosexuality laws. Foote faced a backlash and canceled public appearances after he was threatened on social media, and was subsequently recalled after President Lungu declared him persona non grata.[53]

Geography

Zambia is a landlocked country in southern Africa, with a tropical climate, and consists mostly of high plateaus with some hills and mountains, dissected by river valleys. At 752,614 km2 (290,586 sq mi) it is the 39th-largest country in the world, slightly smaller than Chile. The country lies mostly between latitudes 8° and 18°S, and longitudes 22° and 34°E.

Zambia is drained by two major river basins: the Zambezi/Kafue basin in the center, west, and south covering about three-quarters of the country; and the Congo basin in the north covering about one-quarter of the country. A very small area in the northeast forms part of the internal drainage basin of Lake Rukwa in Tanzania.

In the Zambezi basin, there are a number of major rivers flowing wholly or partially through Zambia: the Kabompo, Lungwebungu, Kafue, Luangwa, and the Zambezi itself, which flows through the country in the west and then forms its southern border with Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe. Its source is in Zambia but it diverts into Angola, and a number of its tributaries rise in Angola's central highlands. The edge of the Cuando River floodplain (not its main channel) forms Zambia's southwestern border, and via the Chobe River that river contributes very little water to the Zambezi because most are lost by evaporation.[54]

Two of the Zambezi's longest and largest tributaries, the Kafue and the Luangwa, flow mainly in Zambia. Their confluences with the Zambezi are on the border with Zimbabwe at Chirundu and Luangwa town respectively. Before its confluence, the Luangwa River forms part of Zambia's border with Mozambique. From Luangwa town, the Zambezi leaves Zambia and flows into Mozambique, and eventually into the Mozambique Channel.

The Zambezi falls about 100 metres (328 ft) over the 1.6 km (0.99 mi) wide Victoria Falls, located in the south-west corner of the country, subsequently flowing into Lake Kariba. The Zambezi valley, running along the southern border, is both deep and wide. From Lake Kariba going east, it is formed by grabens and like the Luangwa, Mweru-Luapula, Mweru-wa-Ntipa and Lake Tanganyika valleys, is a rift valley.

The north of Zambia is very flat with broad plains. In the west the most notable being the Barotse Floodplain on the Zambezi, which floods from December to June, lagging behind the annual rainy season (typically November to April). The flood dominates the natural environment and the lives, society, and culture of the inhabitants and those of other smaller, floodplains throughout the country.

In Eastern Zambia the plateau which extends between the Zambezi and Lake Tanganyika valleys is tilted upwards to the north, and so rises imperceptibly from about 900 m (2,953 ft) in the south to 1,200 m (3,937 ft) in the centre, reaching 1,800 m (5,906 ft) in the north near Mbala. These plateau areas of northern Zambia have been categorised by the World Wildlife Fund as a large section of the Central Zambezian Miombo woodlands ecoregion.[55]

Eastern Zambia shows great diversity. The Luangwa Valley splits the plateau in a curve north-east to south-west, extended west into the heart of the plateau by the deep valley of the Lunsemfwa River. Hills and mountains are found by the side of some sections of the valley, notably in its north-east the Nyika Plateau (2,200 m or 7,218 ft) on the Malawi border, which extend into Zambia as the Mafinga Hills, containing the country's highest point, Mafinga Central (2,339 m or 7,674 ft).[56]

The Muchinga Mountains, the watershed between the Zambezi and Congo drainage basins, run parallel to the deep valley of the Luangwa River and form a sharp backdrop to its northern edge, although they are almost everywhere below 1,700 m (5,577 ft). Their culminating peak Mumpu is at the western end and at 1,892 m (6,207 ft) is the highest point in Zambia away from the eastern border region. The border of the Congo Pedicle was drawn around this mountain.

The southernmost headstream of the Congo River rises in Zambia and flows west through its northern area firstly as the Chambeshi and then, after the Bangweulu Swamps as the Luapula, which forms part of the border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Luapula flows south then west before it turns north until it enters Lake Mweru. The lake's other major tributary is the Kalungwishi River, which flows into it from the east. The Luvua River drains Lake Mweru, flowing out of the northern end to the Lualaba River (Upper Congo River).

Lake Tanganyika is the other major hydrographic feature that belongs to the Congo basin. Its south-eastern end receives water from the Kalambo River, which forms part of Zambia's border with Tanzania. This river has Africa's second highest uninterrupted waterfall, the Kalambo Falls.

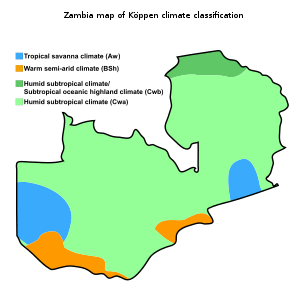

Climate

Zambia is located on the plateau of Central Africa, between 1000 and 1600 m above sea level. The average altitude of 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) generally has a moderate climate. The climate of Zambia is tropical, modified by elevation. In the Köppen climate classification, most of the country is classified as humid subtropical or tropical wet and dry, with small stretches of semi-arid steppe climate in the south-west and along the Zambezi valley.

There are two main seasons, the rainy season (November to April) corresponding to summer, and the dry season (May/June to October/November), corresponding to winter. The dry season is subdivided into the cool dry season (May/June to August), and the hot dry season (September to October/November). The modifying influence of altitude gives the country pleasant subtropical weather rather than tropical conditions during the cool season of May to August.[57] However, average monthly temperatures remain above 20 °C (68 °F) over most of the country for eight or more months of the year.

Biodiversity

There are numerous ecosystems in Zambia, such as forest, thicket, woodland and grassland vegetation types.

Zambia has approximately 12,505 identified species — 63% animal species, 33% plant species and 4% bacterial species and other microorganisms.

There are an estimated 3,543 species of wild flowering plants, consisting of sedges, herbaceous plants and woody plants[58] . The Northern and North-Western provinces of the country especially have the highest diversity of flowering plants. Approximately 53% of flowering plants are rare and occur throughout the country.[59]

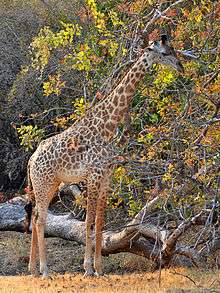

A total of 242 mammal species are found in the country, with most occupying the woodland and grassland ecosystems. The Rhodesian giraffe and Kafue lechwe are some of the well-known subspecies that are endemic to Zambia.[60]

An estimated 757 bird species have been seen in the country, of which 600 are either resident or Afrotropic migrants; 470 breed in the country; and 100 are non-breeding migrants. The Zambian barbet is a species endemic to Zambia.

Roughly 490 known fish species, belonging to 24 fish families, have been reported in Zambia, with Lake Tanganyika having the highest number of endemic species.[61]

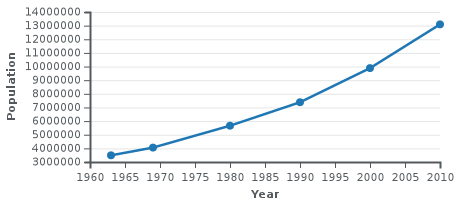

Demographics

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: During the occupation by the British, the Black African population was estimated rather than counted. Source: Central Statistical Office, Zambia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As of the 2010 Zambian census, Zambia's population was 13,092,666. Zambia is ethnically diverse, with 73 distinct tribes. During its occupation by the British between 1911 and 1963, the country attracted immigrants from Europe and the Indian subcontinent, the latter of whom came as laborers. While most Europeans left after the collapse of white minority rule, many Asians remained.

In the first census—conducted on 7 May 1911—there were a total of 1,497 Europeans; 39 Asiatics and an estimated 820,000 Africans. Black Africans were not counted in the six censuses conducted in 1911, 1921, 1931, 1946, 1951, and 1956, prior to independence. By 1956 there were 65,277 Europeans; 5,450 Asiatics; 5,450 Coloureds and an estimated 2,100,000 Africans.

In the 2010 population census, 99.2% were Black Africans and 0.8% consisted of major racial groups.

Zambia is one of the most highly urbanised countries in sub-Saharan Africa with 44% of the population concentrated along the major transport corridors, while rural areas are sparsely populated. The fertility rate was 6.2 as of 2007 (6.1 in 1996, 5.9 in 2001–02).[62]

Largest towns

The onset of industrial copper mining on the Copperbelt in the late 1920s triggered rapid urbanisation. Although urbanisation was overestimated during the colonial period, it was substantial.[63] Mining townships on the Copperbelt soon dwarfed existing centres of population and continued to grow rapidly following Zambian independence. Economic decline on the Copperbelt from the 1970s to the 1990s has altered patterns of urban development but the country's population remains concentrated around the railway and roads running south from the Copperbelt through Kapiri Mposhi, Lusaka, Choma and Livingstone.

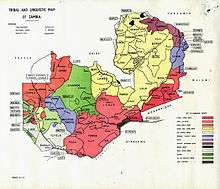

Ethnic groups

The population comprises approximately 73 ethnic groups,[65] most of which are Bantu-speaking. Almost 90% of Zambians belong to the nine main ethnolinguistic groups: the Nyanja-Chewa, Bemba,[66] Tonga,[67] Tumbuka,[68] Lunda, Luvale,[69] Kaonde,[70] Nkoya and Lozi.[71] In the rural areas, ethnic groups are concentrated in particular geographic regions. Many groups are small and not well known. However, all the ethnic groups can be found in significant numbers in Lusaka and the Copperbelt. In addition to the linguistic dimension, tribal identities are relevant in Zambia.[72] These tribal identities are often linked to family allegiance or to traditional authorities. The tribal identities are nested within the main language groups.[73]

Immigrants, mostly British or South African, as well as some white Zambian citizens of British descent, live mainly in Lusaka and in the Copperbelt in northern Zambia, where they are either employed in mines, financial and related activities or retired. There were 70,000 Europeans in Zambia in 1964, but many have since left the country.[36]

Zambia has a small but economically important Asian population, most of whom are Indians and Chinese. There are 13,000 Indians in Zambia. This minority group has a massive impact on the economy controlling the manufacturing sector. An estimated 80,000 Chinese are resident in Zambia.[74] In recent years, several hundred dispossessed white farmers have left Zimbabwe at the invitation of the Zambian government, to take up farming in the Southern province.[75][76]

Zambia has a minority of coloureds of mixed race. During colonialism, segregation separated coloureds, blacks and whites in public places including schools, hospitals, and in housing. There has been an increase in interracial relationships due to Zambia's growing economy importing labor. Coloureds are not recorded on the census but are considered a minority in Zambia.

According to the World Refugee Survey 2009 published by the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, Zambia had a population of refugees and asylum seekers numbering approximately 88,900. The majority of refugees in the country came from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (47,300 refugees from the DRC living in Zambia in 2007), Angola (27,100; see Angolans in Zambia), Zimbabwe (5,400) and Rwanda (4,900).[77]

Beginning in May 2008, the number of Zimbabweans in Zambia began to increase significantly; the influx consisted largely of Zimbabweans formerly living in South Africa who were fleeing xenophobic violence there.[78] Nearly 60,000 refugees live in camps in Zambia, while 50,000 are mixed in with the local populations. Refugees who wish to work in Zambia must apply for permits which can cost up to $500 per year.[77]

Religion

Zambia is a Christian nation according to the 1996 constitution,[80] but a wide variety of religious traditions exist. Traditional religious thoughts blend easily with Christian beliefs in many of the country's syncretic churches. About three-fourths of the population is Protestant while about 20% follow Roman Catholicism. Christian denominations include Catholicism, Anglicanism, Pentecostalism, New Apostolic Church, Lutheranism, Jehovah's Witnesses, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Branhamites, and a variety of Evangelical denominations.

These grew, adjusted and prospered from the missionary settlements (Portuguese and Catholicism in the east from Mozambique) and Anglicanism (British influences) from the south. Except for some technical positions (e.g. physicians), Western missionary roles have been assumed by native believers. After Frederick Chiluba (a Pentecostal Christian) became president in 1991, Pentecostal congregations expanded considerably around the country.[81] Zambia has one of the largest percentage of Seventh-day Adventist per capita in the world, accounting for about 1 in 18 Zambians.[82] The Lutheran Church of Central Africa has over 11,000 members in the country.[83]

Counting only active preachers, Jehovah's Witnesses in Zambia have over 204,000 adherents[84] with over 930,000 attending their annual observance of Christ's death in 2018. These have been preaching there since 1911.[85]

One in 11 Zambians is a member of the New Apostolic Church.[86] With membership above 1,200,000 the Zambia district of the church is the third-largest after Congo East and East Africa (Nairobi).[87]

The Bahá'í population of Zambia is over 160,000,[88] or 1.5% of the population. The William Mmutle Masetlha Foundation run by the Baha'i community is particularly active in areas such as literacy and primary health care. Approximately 1% of the population is Muslims, most of whom live in urban areas and play a large economic role in the country.[89] There are about 500 people who belong to the Ahmadiyya sect.[90] There is also a small Jewish community, composed mostly of Ashkenazis.

Languages

The official language of Zambia is English, which is used for official business and instruction in schools. The main local language, especially in Lusaka, is Nyanja (Chewa), followed by Bemba. In the Copperbelt Bemba is the main language and Nyanja second. Bemba and Nyanja are spoken in the urban areas in addition to other indigenous languages which are commonly spoken in Zambia. These include Lozi, Kaonde, Tonga, Lunda and Luvale, which feature on the Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation (ZNBC) local languages section. The total number of languages spoken in Zambia is 73[92].

Urbanisation has had a dramatic effect on some of the indigenous languages, including the assimilation of words from other languages. Urban dwellers sometimes differentiate between urban and rural dialects of the same language by prefixing the rural languages with 'deep'.

Most will thus speak Bemba and Nyanja in the Copperbelt; Nyanja is dominantly spoken in Lusaka and Eastern Zambia. English is used in official communications and is the language of choice at home among – now common – intertribal families. This evolution of languages has led to Zambian slang heard throughout Lusaka and other major cities. Portuguese has been introduced as a second language into the school curriculum due to the presence of a large Portuguese-speaking Angolan community.[94] French is commonly studied in private schools, while some secondary schools have it as an optional subject. A German course has been introduced at the University of Zambia (UNZA).

Education

The right to equal and adequate education for all is enshrined within the Zambian constitution.[95] The Education Act of 2011 regulates equal and quality education.[96] The Ministry of General Education effectively oversees the provision of quality education through policy and regulation of the education curriculum.

Fundamentally, the aim of education in Zambia is to promote the full and well-rounded development of the physical, intellectual, social, affective, moral, and spiritual qualities of all learners. The education system has three core structures: Early childhood education and Primary education (Grades 1 – 7), Secondary education (Grades 8 – 12) and Tertiary education. Adult Literacy programs are available for semi-literate and illiterate individuals.

The government's annual expenditure on education has increased over the years, increasing from 16.1% in 2006 to 20.2% in 2015.

Health

Zambia is experiencing a generalised HIV/AIDS epidemic, with a national HIV prevalence rate of 12.40% among adults.[98] The maternal mortality rate was 398 per 100,000 live births in 2014, compared to 591 in 2007. Over the same period, the under-5 mortality rate dropped to 75 from 119 per 1,000 live births. The prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS for adults aged 15–49 decreased to 13 per cent in 2013/14, from 16 per cent in 2001/02.[99]

Economy

Presently, Zambia averages between $7.5 billion and $8 billion of exports annually.[100] It totalled $9.1 billion worth of exports in 2018[101] About 60.5% of Zambians live below the recognised national poverty line,[102] with rural poverty rates standing at about 77.9%[103] and urban rates at about 27.5%.[104] Unemployment and underemployment in urban areas are serious problems. Most rural Zambians are subsistence farmers.

Zambia ranked 117th out of 128 countries on the 2007 Global Competitiveness Index, which looks at factors that affect economic growth.[106] Social indicators continue to decline, particularly in measurements of life expectancy at birth (about 40.9 years) and maternal mortality (830 per 100,000 pregnancies).[107]

Zambia fell into poverty after international copper prices declined in the 1970s. The socialist regime made up for falling revenue with several abortive attempts at International Monetary Fund structural adjustment programs (SAPs). The policy of not trading through the main supply route and line of rail to the sea – the territory was known as Rhodesia (from 1965 to 1979), and now known as Zimbabwe – cost the economy greatly. After the Kaunda regime, (from 1991) successive governments began limited reforms. The economy stagnated until the late 1990s. In 2007 Zambia recorded its ninth consecutive year of economic growth. Inflation was 8.9%, down from 30% in 2000.[108]

.png)

Zambia is still dealing with economic reform issues such as the size of the public sector, and improving Zambia's social sector delivery systems.[108] Economic regulations and red tape are extensive, and corruption is widespread. The bureaucratic procedures surrounding the process of obtaining licences encourages the widespread use of facilitation payments.[109] Zambia's total foreign debt exceeded $6 billion when the country qualified for Highly Indebted Poor Country Initiative (HIPC) debt relief in 2000, contingent upon meeting certain performance criteria. Initially, Zambia hoped to reach the HIPC completion point, and benefit from substantial debt forgiveness, in late 2003. As of June of 2020, Zambia is set to default on its debt and the government announced its official intent to pursue a “liability management exercise.”[43]

In January 2003, the Zambian government informed the International Monetary Fund and World Bank that it wished to renegotiate some of the agreed performance criteria calling for privatisation of the Zambia National Commercial Bank and the national telephone and electricity utilities. Although agreements were reached on these issues, subsequent overspending on civil service wages delayed Zambia's final HIPC debt forgiveness from late 2003 to early 2005, at the earliest. In an effort to reach HIPC completion in 2004, the government drafted an austerity budget for 2004, freezing civil service salaries and increasing the number of taxes. The tax hike and public sector wage freeze prohibited salary increases and new hires. This sparked a nationwide strike in February 2004.[110]

The Zambian government is pursuing an economic diversification program to reduce the economy's reliance on the copper industry. This initiative seeks to exploit other components of Zambia's rich resource base by promoting agriculture, tourism, gemstone mining, and hydro-power. In July 2018, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Zambia's President Edgar Lungu signed 12 agreements in capital Lusaka on areas ranging from trade and investment to tourism and diplomacy.[111][112]

Mining

The Zambian economy has historically been based on the copper mining industry. The output of copper had fallen to a low of 228,000 metric tons in 1998 after a 30-year decline in output due to lack of investment, low copper prices, and uncertainty over privatisation. In 2002, following the privatisation of the industry, copper production rebounded to 337,000 metric tons. Improvements in the world copper market have magnified the effect of this volume increase on revenues and foreign exchange earnings.

In 2003, exports of nonmetals increased by 25% and accounted for 38% of all export earnings, previously 35%. The Zambian government has recently been granting licenses to international resource companies to prospect for minerals such as nickel, tin, copper, and uranium.[113] IThe government of Zambia hopes that nickel will take over from copper as the country's top metallic export.[114] In 2009, Zambia was badly hit by the world economic crisis.[115]

Agriculture

Agriculture plays a very important part in Zambia's economy providing many more jobs than the mining industry. A small number of white Zimbabwean farmers were welcomed into Zambia after their expulsion by Robert Mugabe, whose numbers had reached roughly 150 to 300 people as of 2004.[116][117] They farm a variety of crops including tobacco, wheat, and chili peppers on an estimated 150 farms. The skills they brought, combined with general economic liberalisation under the late Zambian president Levy Mwanawasa, has been credited with stimulating an agricultural boom in Zambia. In 2004, for the first time in 26 years, Zambia exported more corn than it imported.[76]

Tourism

Zambia has some of nature's best wildlife and game reserves affording the country with abundant tourism potential. The North Luangwa, South Luangwa and Kafue National Parks have one of the most prolific animal populations in Africa. The Victoria Falls in the Southern part of the country is a major tourist attraction.

With 73 ethnic groups, there is also a myriad of traditional ceremonies that take place every year.

Energy

In 2009, Zambia generated 10.3 TWh of electricity and has been rated high in use of both Solar power and Hydroelectricity.[118] However, early 2015, Zambia began experiencing a serious energy shortage due to the poor 2014/2015 rain season, which resulted in low water levels at the Kariba dam and other major dams.[119] In September 2019, African Green Resources (AGR) announced that it would invest $150 million in 50 megawatt (MW) solar farm, along with irrigation dam and expanding the existing grain silo capacity by 80,000 tonnes.[120]

Manufacturing

Culture

Prior to the establishment of modern Zambia, the inhabitants lived in independent tribes, each with its own way of life. One of the results of the colonial era was the growth of urbanisation. Different ethnic groups started living together in towns and cities, influencing each other as well as adopting a lot of the European culture. The original cultures have largely survived in rural areas with some outside influence such as Christianity being widely practiced. In the urban setting, there is a continuous integration and evolution of these cultures to produce what is now called "Zambian culture".

Traditional culture is very visible through colourful annual Zambian traditional ceremonies. Some of the more prominent are: Kuomboka and Kathanga (Western Province), Mutomboko (Luapula Province), Kulamba and Ncwala (Eastern Province), Lwiindi and Shimunenga (Southern Province), Lunda Lubanza (North Western), Likumbi Lyamize (North Western)[121], Mbunda Lukwakwa (North Western Province), Chibwela Kumushi (Central Province), Vinkhakanimba (Muchinga Province), Ukusefya Pa Ng'wena (Northern Province).

Popular traditional arts are mainly in pottery, basketry (such as Tonga baskets), stools, fabrics, mats, wooden carvings, ivory carvings, wire craft, and copper crafts. Most Zambian traditional music is based on drums (and other percussion instruments) with a lot of singing and dancing. In the urban areas, foreign genres of music are popular, in particular Congolese rumba, African-American music and Jamaican reggae. Several psychedelic rock artists emerged in the 1970s to create a genre known as Zam-rock, including WITCH, Musi-O-Tunya, Rikki Ililonga, Amanaz, the Peace, Chrissy Zebby Tembo, Blackfoot, and the Ngozi Family.

Media

The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Services In Zambia is responsible for the Zambian News Agency, while there are also numerous media outlets throughout the country which include; television stations, newspapers, FM radio stations, and Internet news websites.

Sports

Zambia declared its independence on the day of the closing ceremony of the 1964 Summer Olympics, thereby becoming the first country ever to have entered an Olympic game as one country, and leave it as another. In 2016, Zambia participated for the thirteenth time in the Olympic games. Two medals were won. The medals were won successively in boxing and on the track. In 1984 Keith Mwila won a bronze medal in the light flyweight. In 1996 Samuel Matete won a silver medal in the 400-metre hurdles. Zambia has never participated in the Winter Olympics.

Football is the most popular sport in Zambia, and the Zambia national football team has had its triumphant moments in football history. At the Seoul Olympics in 1988, the national team defeated the Italian national team with a score of 4–0. Kalusha Bwalya, Zambia's most celebrated football player, and one of Africa's greatest football players in history scored a hat trick in that match. However, to this day, many pundits say the greatest team Zambia has ever assembled was the one that perished on 28 April 1993 in a plane crash at Libreville, Gabon. Despite this, in 1996, Zambia was ranked 15th on the official FIFA World Football Team rankings, the highest attained by any southern African team. In 2012, Zambia won the African Cup of Nations for the first time after losing in the final twice. They beat Côte d'Ivoire 8–7 in a penalty shoot-out in the final, which was played in Libreville, just a few kilometers away from the plane crash 19 years previously.[122]

Rugby Union, boxing and cricket are also popular sports in Zambia. Notably, at one point in the early 2000s, the Australia and South Africa national rugby teams were captained by players born in the same Lusaka hospital, George Gregan and Corné Krige. Zambia boasts having the highest rugby poles in the world, located at Luanshya Sports Complex in Luanshya.[123]

Rugby union in Zambia is a minor but growing sport. They are currently ranked 73rd by the IRB and have 3,650 registered players and three formally organised clubs.[124] Zambia used to play cricket as part of Rhodesia. Zambia has also strangely provided a shinty international, Zambian-born Eddie Tembo representing Scotland in the compromise rules Shinty/Hurling game against Ireland in 2008.[125]

In 2011, Zambia was due to host the tenth All-Africa Games, for which three stadiums were to be built in Lusaka, Ndola, and Livingstone.[126] The Lusaka stadium would have a capacity of 70,000 spectators while the other two stadiums would hold 50,000 people each. The government was encouraging the private sector to get involved in the construction of the sports facilities because of a shortage of public funds for the project. Zambia later withdrew its bid to host the 2011 All-Africa Games, citing a lack of funds. Hence, Mozambique took Zambia's place as host.

Zambia also produced the first black African (Madalitso Muthiya) to play in the United States Golf Open,[127] one of the four major golf tournaments.

In 1989, the country's basketball team had its best performance when it qualified for the FIBA Africa Championship and thus finished as one of Africa's top ten teams.[128]

In 2017, Zambia hosted and won the Pan-African football tournament U-20 African Cup of Nation for players age 20 and under.[129]

Music and dance

Zambia's culture has been an integral part of their development post-independence such as the uprising of cultural villages and private museums. The music which introduced dance is part of their cultural expression and it embodies the beauty and spectacle of life in Zambia, from the intricacies of the talking drums to the Kamangu drum used to announce the beginning of Malaila traditional ceremony. Dance as a practice serves as a unifying factor bringing the people together as one.[130][131]

Zamrock is a musical genre that emerged in the 1970s, and has developed a cult following in the West. Zamrock has been described as mixing traditional Zambian music with heavy repetitive riffs similar to groups such as Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Black Sabbath, Rolling Stones, Deep Purple, and Cream.[132][133] Notable groups in the genre include Rikki Ililonga and his band Musi-O-Tunya, WITCH, Chrissy "Zebby" Tembo, and Paul Ngozi and his Ngozi Family.[134][135]

References

- Census of Population and Housing National Analytical Report 2010 Central Statistical Office, Zambia

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_za.html

- United Nations Statistics Division. "Population by sex, rate of population increase, surface area and density" (PDF). Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Central Statistical Office, Government of Zambia. "2010 Census Population Summaries" (PDF). Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "Zambia". International Monetary Fund.

- "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Zambia". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "United Nations Statistics Division- Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49)". Unstats.un.org. 31 August 1999. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "History | Zambian High Commission". www.zambiapretoria.net. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Andy DeRoche, Kenneth Kaunda, the United States, and Southern Africa (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

- Zambian President Michael Sata dies in London – BBC News. Bbc.com (29 October 2014). Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- Guy Scott takes the interim role after Zambian president Sata's death | World news. The Guardian. Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- Karlyn Eckman (FAO, 2007).GENDER MAINSTREAMING IN FORESTRY IN AFRICA ZAMBIA.

- Ngoma, Jumbe (18 December 2010). "World Bank President Praises Reforms In Zambia, Underscores Need For Continued Improvements In Policy And Governance". World Bank.

- Everett-Heath, John (7 December 2017). The Concise Dictionary of World Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192556462.

- Holmes, Timothy (1998). Cultures of the World: Zambia. Tarrytown, New York: Times Books International. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-7614-0694-5.

- Malcolm Southwood, Bruce Cairncross & Mike S. Rumsey (2019). "Minerals of the Kabwe ("Broken Hill") Mine, Central Province, Zambia, Rocks & Minerals". Rocks & Minerals. 94:2: 114–149.

- Taylor, Scott D. "Culture and Customs of Zambia" (PDF). Greenwood Press. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Clay, Gervas (1945). History of the Mankoya District. Rhodes-Livingstone Institute.

- The elites of Barotseland, 1878–1969: a political history of Zambia's Western Province: a. Gerald L. Caplan, C. Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd, 1970, ISBN 0900966386

- Bantu-Languages.com, citing Maniacky 1997

- "Instructions and Travel Diary that Governor Francisco Joze de Lacerda e Almeida Wrote about His Travel to the Center of Africa, Going to the River of Sena, in the Year of 1798". Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Communications., Craig Hartnett of NinerNet. "Portuguese Expedition to Northern Rhodesia, 1798–99 – Great North Road (GNR, Northern Rhodesia, Zambia)". www.greatnorthroad.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Livingstone Discovers Victoria Falls, 1855". www.eyewitnesstohistory.com. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "HISTORY". THE PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION WEBSITE.

- Livingstone Tourism Association. "Destination:Zambia – History and Culture". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- Human Rights & Documentation Centre. "Zambia: Historical Background". Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- Burnham, Frederick Russell (1899). "Northern Rhodesia". In Wills, Walter H. (ed.). . Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. pp. 177–180.

- Pearson Education. "Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Federation of". Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- "Zambia - Post-Colonial History". globalsecurity.org.

- "Alice Lenshina". The British Empire. 26 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- WILLSON, John Michael (born 15 July 1931). BDOHP Biographical Details and Interview Index. chu.cam.ac.uk

- 1964: President Kaunda takes power in Zambia. BBC 'On This Day'.

- Raeburn, Michael (1978). We are everywhere: Narratives from Rhodesian guerillas. Random House. pp. 1–209. ISBN 978-0394505305.

- "GREEN LEADER. OPERATION GATLING, THE RHODESIAN MILITARY'S RESPONSE TO THE VISCOUNT TRAGEDY". Archived from the original on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Nelson, Harold (1983). Zimbabwe: A Country Study. Claitors Publishing Division. pp. 54–137. ISBN 978-0160015984.

- Kaplan, Irving (1971). Area Handbook for the Republic of South Africa. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 404–405.

- Evans, M. (1984). "The Front-Line States, South Africa and Southern African Security: Military Prospects and Perspectives" (PDF). Zambezia. 12: 1.

- "Zambia (12/08)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Zambia's Debt: China, Creditors, and COVID-19". Crossfire KM. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "About Zambia". 20 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Bartlett, David M. C. (2000). "Civil Society and Democracy: A Zambian Case Study". Journal of Southern African Studies. 26 (3): 429–446. ISSN 0305-7070.

- Zambian President Michael Sata dies in London. BBC. 29 October 2014

- Defence Minister Lungu wins Zambia's disputed presidential race. Associated Press via Yahoo News. 24 January 2015

- "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

- "Zambia", Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, U.S. Department of State, 22 March 2013.

- "State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 17 May 2016.

- Avery, Daniel (4 April 2019). "71 Countries Where Homosexuality is Illegal". Newsweek.

- "Biggest Ever Studies on Attitudes to Religion and Morality in Africa Released". Newstime Africa. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- "US recalls ambassador to Zambia after gay rights row". BBC News. 24 December 2019.

- Beilfuss, Richard and dos Santos, David (2001) "Patterns of Hydrological Change in the Zambezi Delta, Mozambique". Archived 17 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Working Paper No 2 Program for the Sustainable Management of Cahora Bassa Dam and The Lower Zambezi Valley.

- "Geography | Zambian High Commission". www.zambiapretoria.net. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Mafinga South and Mafinga Central: the highest peaks in Zambia". Footsteps on the Mountain blog. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- Spectrum Guide to Zambia. Camerapix International Publishing, Nairobi, 1996. ISBN 1874041148.

- Bolnick, Doreen; Bingham (2007). A guide to the common wild flowers of Zambia and neighbouring regions 2nd Edition. Lusaka: Wildlife & Environmental Conservation Society of Zambia. p. 75. ISBN 9789982180634.

- Zambia- Ministry of Lands Natural Resources (June 2015). "Ministry of Lands Natural Resources and Environmental Protection : United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity Fifth National Report". Zambia- Ministry of Lands Natural Resources.

- Ministry of Lands (June 2015). "Ministry of Lands Natural Resources and Environmental Protection:United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity Fifth National Report". Zambia - Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources.

- "Fish – arczambia.com". Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Welcome to the Official site of Zambian Statistics". Zamstats.gov.zm. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- Potts, Deborah (2005). "Counter-urbanisation on the Zambian Copperbelt? Interpretations and implications". Urban Studies. 42 (4): 583–609. doi:10.1080/00420980500060137.

- http://citypopulation.de/Zambia-Cities.html

- "Zambia - People". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Bemba | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Tonga | African people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Tumbuka | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Luvale | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Kaonde | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Lozi | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- GROWup - Geographical Research On War, Unified Platform. "Ethnicity in Zambia". ETH Zurich. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- Posner, Daniel (2005). Institutions and Ethnic Politics in Zambia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Zambians wary of "exploitative" Chinese employers. Irinnews.org. 23 November 2006.

- "Zim's Loss, Zam's gain: White Zimbabweans making good in Zambia". The Economist. June 2004. Archived from the original on 15 February 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- Thielke, Thilo (27 December 2004). "Settling in Zambia: Zimbabwe's Displaced Farmers Find a New Home". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- "World Refugee Survey 2009". U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013.

- "Zambia: Rising levels of resentment towards Zimbabweans". IRIN News. 9 June 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- Census of Population and Housing National Analytical Report 2010. Central Statistical office, Zambia

- "Constitution of Zambia, 1991(Amended to 1996)". Scribd.com. 30 June 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Steel, Matthew (2005). Pentecostalism in Zambia: Power, Authority and the Overcomers. University of Wales. MSc Dissertation.

- "Zambia Union Conference – Adventist Organizational Directory". Adventistdirectory.org. 17 October 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Lutheran Church of Central Africa — Zambia". Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017.

- "2018 Country and Territory Report".

- "Zambia — Watchtower ONLINE LIBRARY". wol.jw.org.

- Hayashida, Nelson Osamu (1999). Dreams in the African Literature: The Significance of Dreams and Visions Among Zambian Baptists. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-0596-9.

- "Membership figures of the global Church as at the end of 2009: New Apostolic Church International (NAC)". www.nak.org. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "The Largest Baha'i Communities". Adherents.com. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2010 – Zambia. State.gov. Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- Some basics of religious education in Zambia. 2007. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Census of Population and Housing National Analytical Report 2010. Central Statistical office, Zambia

- "Encyclopedia Britanica". 26 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Census of Population and Housing National Analytical Report 2010. Central Statistical office, Zambia

- Zambia to introduce Portuguese into school curriculum. Archived 8 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Laws of Zambia". National Assembly of Zambia. National Assembly of Zambia. 1996. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- "The Education Act (2011)". National Assembly of Zambia. National Assembly of Zambia. 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- "Budget Speeches". Republic of Zambia Ministry of Finance. Republic of Zambia Ministry of Finance. 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "CIA world factbook - HIV/AIDS adult prevalence rate".

- "Children in Zambia". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Zambia's Minister of Commerce, Trade, & Industry Robert K Sichinga on the country's economic performance. Theprospectgroup.com (10 August 2012). Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- Workman, Daniel. "Zambia's Top 10 Exports". World's Top Exports. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- "Population below national poverty line, total, percentage". Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- "Population below national poverty line, rural, percentage". Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- "Population below national poverty line, urban, percentage". Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- "Budget Speeches". Republic of Zambia Ministry of Finance. Republic of Zambia Ministry of Finance. 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Zambia Country Brochure" (PDF). World Bank.

- Human Development Report 2007/2008. Palgrave Macmillan. 2007. ISBN 978-0-230-54704-9

- "Background Note: Zambia". Department of State.

- "Business Corruption in Zambia". Business Anti-Corruption Portal. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- The World Bank and IMF's long shadow in Zambia's copper mines. eurodad.org. 20 February 2008

- "Turkey and Zambia sign agreements to boost bilateral ties". Turkey and Zambia sign agreements to boost bilateral ties (in Turkish). Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- "Turkey, Zambia sign 12 deals to boost bilateral ties". Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Pennysharesonline.com, City Equities Limited (14 July 2006). "Albidon signs agreement with Zambian government". Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2006.

- "Economy". The Provincial Administration Website.

- Chinese keep low profile to cash in on the slump in Zambia. The Times. 24 January 2009.

- "Zim's Loss, Zam's gain: White Zimbabweans making good in Zambia", The Economist, June 2004, retrieved 28 August 2009

- LaFraniere, Shannon (21 March 2004), "Zimbabwe's White Farmers Start Anew in Zambia", The New York Times, retrieved 28 August 2009

- "404" (PDF). www.irena.org. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Sunday Chilufya Chanda (28 September 2016). "Zambia : ARTICLE 70 of the UPND Constitution is Inconsistent with the Republican Constitution, it should be deemed illegal".

- "Zambia farm input supplier plans to invest $150 million in farming". Reuters. 9 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Ellert, Henrik (2004). The magic of the makishi: masks and traditions in Zambia. Bath, UK: CBC publishing. pp. 38–63. ISBN 0951520997.

- "Zambia score emotional African Cup win". Sydney Morning Herald. 13 February 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "Sport | Zambian High Commission". www.zambiapretoria.net. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Zambia. International Rugby Board

- Tembo's return is boost for Glen Archived 11 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. inverness-courier.co.uk. 15 May 2009

- "Zambia to build three stadia for 2011 All-Africa Games". People's Daily Online. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- "Zambia's Madalitso Muthiya a pioneer". Chicago Tribune. 5 May 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- 1989 African Championship for Men, ARCHIVE.FIBA.COM. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "Zambia outsmart South Africa to win record Cosafa U20 crown". Lusaka Times. 16 December 2016.

- "The Unrivaled Zambian Culture". Ayiba Magazine. 14 June 2016.

- "Zambia Music « LastNaijaMusic". LastNaijaMusic.

- "Salt & thunder: The mind-altering rock of 1970s Zambia". Music In Africa. 11 December 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- S, Henning Goranson; Press, berg for Think Africa; Network, part of the Guardian Africa (22 July 2013). "Why Zamrock is back in play". the Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "We're a Zambian Band". theappendix.net. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- WITCH Archived 14 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine on Dusted Magazine (Apr. 15, 2010)

Further reading

- Ferguson, James (1999). Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life in the Zambian Copperbelt. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21701-0.

- Ihonvbere, Julius, Economic Crisis, Civil Society and Democratisation: The Case of Zambia, (Africa Research & Publications, 1996)

- LaMonica, Christopher, Local Government Matters: The Case of Zambia , (Lambert Academic Publishing, 2010)

- Mcintyre, Charles, Zambia (Bradt Travel Guides), (Bradt Travel Guides, 2008)

- Murphy, Alan and Luckham, Nana, Zambia and Malawi (Lonely Planet Multi Country Guide), (Lonely Planet Publications, 2010)

- Phiri, Bizeck Jube, A Political History of Zambia: From the Colonial Period to the 3rd Republic, (Africa Research & Publications, 2005)

- Roberts, Andrew, A History of Zambia, (Heinemann, 1976)

- Sardanis, Andrew, Africa: Another Side of the Coin: Northern Rhodesia's Final Years and Zambia's Nationhood, (I.B.Tauris, 2003)

- Various, One Zambia, Many Histories: Towards a History of Post-colonial Zambia, (Brill, 2008)

- DeRoche, Andy Kenneth Kaunda, the United States and Southern Africa (London: Bloomsbury, 2016)

External links

- Official government website

- "Zambia". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Zambia Corruption Profile from the Business Anti-Corruption Portal

- Zambia at Curlie

- Zambia profile from the BBC News

- Key Development Forecasts for Zambia from International Futures

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Zambia

- First early human fossil found in Africa makes debut

.svg.png)