European exploration of Africa

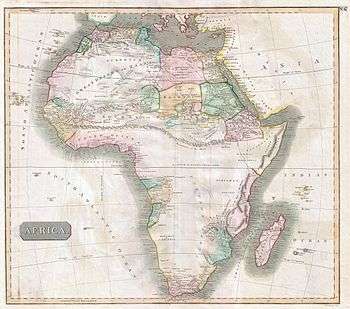

The geography of North Africa has been reasonably well known among Europeans since classical antiquity in Greco-Roman geography. Northwest Africa (the Maghreb) was known as either Libya or Africa, while Egypt was considered part of Asia.

European exploration of Sub-Saharan Africa begins with the Age of Discovery in the 15th century, pioneered by Portugal under Henry the Navigator. The Cape of Good Hope was first reached by Bartolomeu Dias on 12 March 1488, opening the important sea route to India and the Far East, but European exploration of Africa itself remained very limited during the 16th and 17th centuries. The European powers were content to establish trading posts along the coast while they were actively exploring and colonizing the New World. Exploration of the interior of Africa was thus mostly left to the Arab slave traders, who in tandem with the Muslim conquest of Sudan established far-reaching networks and supported the economy of a number of Sahelian kingdoms during the 15th to 18th centuries.

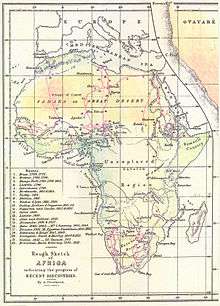

At the beginning of the 19th century, European knowledge of the geography of the interior of Sub-Saharan Africa was still rather limited. Expeditions exploring Southern Africa were made during the 1830s and 1840s, so that around the midpoint of the 19th century and the beginning of the colonial Scramble for Africa, the unexplored parts were now limited to what would turn out to be the Congo Basin and the African Great Lakes. This "Heart of Africa" remained one of the last remaining "blank spots" on world maps of the later 19th century (alongside the Arctic, Antarctic and the interior of the Amazon basin). It was left for 19th-century European explorers, including those searching for the famed sources of the Nile, notably John Hanning Speke, Sir Richard Burton, David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley, to complete the exploration of Africa by the 1870s. After this, the general geography of Africa was known, but it was left to further expeditions during the 1880s onward, notably, those led by Oskar Lenz, to flesh more detail such as the continent's geological makeup.

Antiquity

The Phoenicians explored North Africa, establishing a number of colonies, the most prominent of which was Carthage. Carthage itself conducted exploration of West Africa. The first circumnavigation of the African continent was probably made by Phoenician sailors, in an expedition commissioned by Egyptian pharaoh Necho II, circa 600 BC which took three years. A report of this expedition is provided by Herodotus (4.37). They sailed south, rounded the Cape heading west, made their way north to the Mediterranean, and then returned home. He states that they paused each year to sow and harvest grain. Herodotus himself is sceptical of the historicity of this feat, which would have taken place about 120 years before his birth; however, the reason he gives for disbelieving the story is the sailors' reported claim that when they sailed along the southern coast of Africa, they found the Sun stood to their right, in the north; Herodotus, who was unaware of the spherical shape of the Earth found this impossible to believe. Some commentators took this circumstance as proof that the voyage is historical, but other scholars still dismiss the report as unlikely.[1]

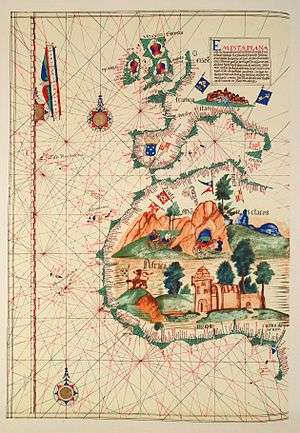

The West African coast may have been explored by Hanno the Navigator in an expedition c.500 BC.[2] The report of this voyage survives in a short Periplus in Greek, which was first cited by Greek authors in the 3rd century BC.[3]:162–3 There is some uncertainty as to how far precisely Hanno reached; he clearly sailed as far as Sierra Leone, and may have continued as far as Guinea or even Gabon.[4] However, Robin Law notes that some commentators have argued that Hanno's exploration may have taken him no farther than southern Morocco.[5]

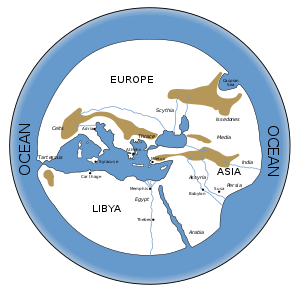

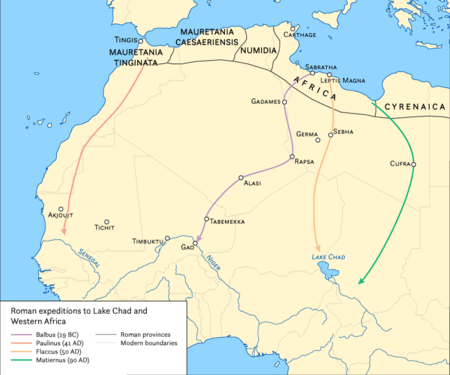

Africa is named for the Afri people who settled in the area of current-day Tunisia. The Roman province of Africa spanned the Mediterranean coast of what is now Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria. The parts of North Africa north of the Sahara were well known in antiquity. Prior to the 2nd century BC, however, Greek geographers were unaware that the landmass then known as Libya expanded south of the Sahara, assuming that the desert bounded on the outer Ocean. Indeed, Alexander the Great, according to Plutarchus' Lives, considered sailing from the mouths of the Indus back to Macedonia passing south of Africa as a shortcut compared to the land route. Even Eratosthenes around 200 BC still assumed an extent of the landmass no further south than the Horn of Africa.

By the Roman imperial period, the Horn of Africa was well-known to Mediterranean geographers. The trading post of Rhapta, described as "the last marketplace of Azania," may correspond to the coast of Tanzania. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, dated to the 1st century AD, appears to extend geographical knowledge further south, to Southeast Africa. Ptolemy's world map of the 2nd century is well aware that the African continent extends significantly further south than the Horn of Africa, but has no geographic detail south of the equator (it is unclear whether it is aware of the Gulf of Guinea).[6]

Arab slave trade

In the medieval period, the exploration of the interior of the Sahara and the Sahel as well as along the Swahili coast as far as Mozambique was the project of Muslim conquests and slave trade. It was at Mozambique that the Arab "clockwise" and the Portuguese "counter-clockwise" routes of exploration would meet at the end of the 15th century.

Following its 8th-century conquest of North Africa, Arab Muslims ventured into Sub-Saharan Africa first along the Nile Valley towards Nubia, and later also across the Sahara towards West Africa. They were interested in the trans-Saharan trade, especially in slaves. This expansion of Arab and Islamic culture was a gradual process, lasting throughout most of the Middle Ages. The Christian kingdoms of Nubia came under pressure from the 7th century, but they resisted for several centuries. The Kingdom of Makuria and Old Dongola collapsed by the beginning of the 14th century. A significant role in the spread of Islam in Africa was taken by Sufi orders during the 9th to 14th centuries, who spread south along trade routes between North Africa and the sub-Saharan kingdoms of Ghana and Mali. On the West African coast, they set up zawiyas on the shores of the River Niger. The Mali Empire became Islamic following the pilgrimage of Musa I of Mali in 1324. Timbuktu became an important center of Islamic culture south of the Sahara. Alodia, the last remnant of Christian Nubia, was destroyed by the Funj in 1504.

Middle Ages

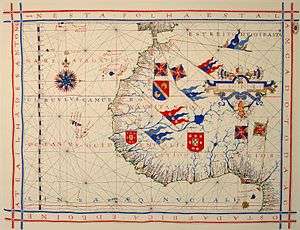

Jaume Ferrer sailed from Majorca down the West African coast to find the legendary "River of Gold" in 1346, but the outcome of his quest and his fate are unknown.

Early Portuguese expeditions

Portuguese explorer Prince Henry, known as the Navigator, was the first European to methodically explore Africa and the oceanic route to the Indies. From his residence in the Algarve region of southern Portugal, he directed successive expeditions to circumnavigate Africa and reach India. In 1420, Henry sent an expedition to secure the uninhabited but strategic island of Madeira. In 1425, he tried to secure the Canary Islands as well, but these were already under firm Castilian control. In 1431, another Portuguese expedition reached and annexed the Azores.

Naval charts of 1339 show that the Canary Islands were already known to Europeans. In 1341, Portuguese and Italian explorers prepared a joint expedition. In 1342 the Catalans organized an expedition captained by Francesc Desvalers to the Canary Islands that set sail from Majorca. In 1344, Pope Clement VI named French admiral Luis de la Cerda Prince of Fortune, and sent him to conquer the Canaries. In 1402, Jean de Bethencourt and Gadifer de la Salle sailed to conquer the Canary Islands but found them already plundered by the Castilians. Although they did conquer the isles, Bethencourt's nephew was forced to cede them to Castile in 1418.

In 1455 and 1456 two Italian explorers, Alvise Cadamosto from Venice and Antoniotto Usodimare from Genoa, together with an unnamed Portuguese captain and working for Prince Henry of Portugal, followed the Gambia river, visiting the land of Senegal, while another Italian sailor from Genoa, Antonio de Noli, also on behalf of Prince Henry, explored the Bijagós islands, and, together with the Portuguese Diogo Gomes, the Cape Verde archipelago. Antonio de Noli, who became the first governor of Cape Verde (and the first European colonial governor in Sub-Saharan Africa), is also considered the discoverer of the First Islands of Cape Verde.[7]

Along the western and eastern coasts of Africa, progress was also steady; Portuguese sailors reached Cape Bojador in 1434 and Cape Blanco in 1441. In 1443, they built a fortress on the island of Arguin, in modern-day Mauritania, trading European wheat and cloth for African gold and slaves. It was the first time that the semi-mythic gold of the Sudan reached Europe without Muslim mediation. Most of the slaves were sent to Madeira, which became, after thorough deforestation, the first European plantation colony. Between 1444 and 1447, the Portuguese explored the coasts of Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea. In 1456, the Venetian captain Alvise Cadamosto, under Portuguese command, explored the islands of Cape Verde. In 1462, two years after Prince Henry's death, Portuguese sailors explored the Bissau islands and named Serra Leoa (Lioness Mountains).

In 1469, Fernão Gomes rented the rights of African exploration for five years. Under his direction, in 1471, the Portuguese reached modern Ghana and settled in A Mina (the mine), today's Elmina. They had finally reached a country with an abundance of gold, hence the historical name of "Gold Coast" that Elmina would eventually receive.

In 1472, Fernão do Pó discovered the island that would bear his name for centuries (now Bioko) and an estuary abundant in shrimp (Portuguese: camarão,), giving its name to Cameroon.

Soon after, the equator was crossed by Europeans . Portugal established a base in Sāo Tomé that, after 1485, was settled with criminals. After 1497, expelled Spanish and Portuguese Jews were also sent there.

In 1482, Diogo Cão found the mouth of a large river and learned of the existence of a great kingdom, Kongo. In 1485, he explored the river upstream as well.

But the Portuguese wanted, above anything else, to find a route to India and kept trying to circumnavigate Africa. In 1485, the expedition of João Afonso d'Aveiros, with the German astronomer Martin of Behaim as part of the crew, explored the Bight of Benin (Kingdom of Benin), returning information about African king Ogane.

In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias and his pilot Pêro de Alenquer, after putting down a mutiny, turned a cape where they were caught by a storm, naming it Cape of Storms. They followed the coast for a while realizing that it kept going eastward with even some tendency to the north. Lacking supplies, they turned around with the conviction that the far end of Africa had finally been reached. Upon their return to Portugal, the promising cape was renamed Cape of Good Hope.

Some years later, Christopher Columbus landed in America under rival Castilian command. Pope Alexander VI decreed the Inter caetera bull, dividing the non-Christian parts of the world between the two rival Catholic powers, Spain and Portugal.

Finally, in the years 1497 to 1498, Vasco da Gama, again with Alenquer as a pilot, took a direct route to Cape of Good Hope, via St. Helena. He went beyond the farthest point reached by Dias and named the country Natal. Then he sailed northward, making land at Quelimane (Mozambique) and Mombasa, where he found Chinese traders, and Malindi (both in modern Kenya). In this town, he recruited an Arab pilot who led the Portuguese directly to Calicut. On August 28, 1498, King Manuel of Portugal informed the Pope of the good news that Portugal had reached India.

Egypt and Venice reacted to this news with hostility; from the Red Sea, they jointly attacked the Portuguese ships that traded with India. The Portuguese defeated these ships near Diu in 1509. The Ottoman Empire's indifferent reaction to Portuguese exploration left Portugal in almost exclusive control of trade through the Indian Ocean. They established many bases along the eastern coast of Africa except for Somalia (See Ajuran-Portuguese wars). The Portuguese also captured Aden in 1513.

One of the ships under command of Diogo Dias arrived at a coast that was not in East Africa. Two years later, a chart already showed an elongated island east of Africa that bore the name Madagascar. But only a century later, between 1613 and 1619, did the Portuguese explore the island in detail. They signed treaties with local chieftains and sent the first missionaries, who found it impossible to make locals believe in Hell, and were eventually expelled.

Early modern history

Portuguese

The Portuguese presence in Africa soon interfered with existing Arab trade interests. By 1583, the Portuguese established themselves in Zanzibar and on the Swahili coast. The Kingdom of Congo was converted to Christianity in 1495; its king taking the name of João I. The Portuguese also established their trade interests in the Kingdom of Mutapa in the 16th century, and in 1629 placed a puppet ruler on the throne.

The Portuguese (and later also the Dutch) also became involved in the local slave economy, supporting the state of the Jaggas, who performed slave raids in the Congo.

They also used the Kongo to weaken the neighbor realm of Ndongo, where Queen Nzinga put a fierce but eventually doomed resistance to Portuguese and Jagga ambitions. Portugal intervened militarily in these conflicts, creating the basis for their colony of Angola. In 1663, after another conflict, the royal crown of Kongo was sent to Lisbon. Nevertheless, a diminished Kongo Kingdom would still exist until 1885, when the last Manicongo, Pedro V, ceded his almost non-existent domain to Portugal.

The Portuguese dealt with the other major state of Southern Africa, the Monomotapa (in modern Zimbabwe), in a similar manner: Portugal intervened in a local war hoping to get abundant mineral riches, imposing a protectorate. But with the authority of the Monomotapa diminished by the foreign presence, anarchy took over. The local miners migrated and even buried the mines to prevent them from falling into Portuguese hands. When in 1693 the neighboring Cangamires invaded the country, the Portuguese accepted their failure and retreated to the coast.

Dutch

Beginning in the 17th century, the Netherlands began exploring and colonizing Africa. While the Dutch were waging a long war of independence against Spain, Portugal had temporarily united with Spain, starting in 1580 and ending in 1640. As a result, the growing colonial ambitions of the Netherlands were mostly directed against Portugal.

For this purpose, two Dutch companies were founded: the West Indies Company, with power over all the Atlantic Ocean, and the East Indies Company, with power over the Indian Ocean.

The West India Company conquered Elmina in 1637 and Luanda in 1640. In 1648, they were expelled from Luanda by the Portuguese. Overall the Dutch built 16 forts in different places, including Gorée in Senegal, partly overtaking Portugal as the main slave-trading power. The Dutch Gold Coast and Dutch Slave Coast were successful.

But in the colony of Dutch Loango-Angola, the Portuguese managed to expel the Dutch.

In Dutch Mauritius the colonization started in 1638 and ended in 1710, with a brief interruption between 1658 and 1666. Numerous governors were appointed, but continuous hardships such as cyclones, droughts, pest infestations, lack of food, and illnesses finally took their toll, and the island was definitively abandoned in 1710.

The Dutch left a lasting impact in South Africa, a region ignored by Portugal that the Dutch eventually decided to use as a station in their route to East Asia. Jan van Riebeeck founded Cape Town in 1652, starting the European exploration and colonization of South Africa.

Other early modern European presence

Almost at the same time as the Dutch, a few other European powers attempted to create their own outposts for the African slave trade.

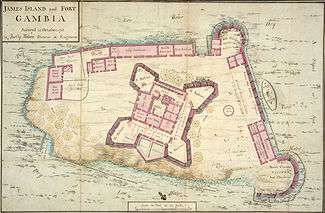

As early as 1530, English merchant adventurers started trading in West Africa, coming into conflict with Portuguese troops. In 1581, Francis Drake reached the Cape of Good Hope. In 1663, the English built Fort James in Gambia. One year later, another English colonial expedition attempted to settle southern Madagascar, resulting in the death of most of the colonists. The English forts on the West African coast were eventually taken by the Dutch.

In 1626, the French Compagnie de l'Occident was created. This company expelled the Dutch from Senegambia (Senegal), making it the first French domain in Africa, they also conquered the island of Arguin.

France also set her eyes on Madagascar, the island that had been used since 1527 as a stop in travels to India. In 1642, the French East India Company founded a settlement in southern Madagascar called Fort Dauphin. The commercial results of this settlement were scarce and, again, most of the settlers died. One of the survivors, Etienne de Flacourt, published a History of the Great Island of Madagascar and Relations, which was for a long time the main European source of information about the island. Further settlement attempts had no more success but, in 1667, François Martin led the first expedition to the Malagasy heartland, reaching Lake Alaotra. In 1665, France officially claimed Madagascar, under the name of Île Dauphine. However, little colonial activity would take place in Madagascar until the 19th century.

In 1651, the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (a vassal of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) gained a colony in Africa on St. Andrew's Island at the Gambia River and established the Jacob Fort there. The Duchy also took other local lands including St. Mary Island (modern-day Banjul) and Fort Jillifree

In 1650, Swedish merchants founded Swedish Gold Coast in modern Ghana following the foundation of the Swedish Africa Company (1649). In 1652 the foundations were laid of the fort Carlsborg.In 1658 Fort Carlsborg was seized and made part of the Danish Gold Coast colony, then to the Dutch Gold Coast. Later on the local population started a successful uprising against their new masters and in December 1660 the King of the Akan people subgroup-Efutu again offered Sweden control over the area, but in 1663 were seized by the Danish after a long defense of Fort Christiansborg.

The Dano-Norwegian colonized the Danish Gold Coast, from 1674 to 1755 the settlements were administered by the Danish West India-Guinea Company. From December 1680 to 29 August 1682, the Portuguese occupied Fort Christiansborg. In 1750 it was made a Danish crown colony. From 1782 to 1785 it was under British occupation. From 1814 it was made part of the territory of Denmark.

In 1677, King Frederick William I of Prussia sent an expedition to the western coast of Africa. The commander of the expedition, Captain Blonk, signed agreements with the chieftains of the Gold Coast. There, the Prussians built a fort named Gross Friederichsburg and restored the abandoned Portuguese fort of Arguin. But in 1720, the king decided to sell these bases to the Netherlands for 7,000 ducats and 12 slaves, six of them chained with pure gold chains.

In 1777, the Spanish Empire and Portuguese Empire signed the Treaty of San Ildefonso in which Portugal give the islands of Annobón and Fernando Poo in waters of the Gulf of Guinea, as well as the Guinean coast between the Niger River and the Ogooué River, to Spain.

The British expressed their interest by the formation in 1788 of The Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa. The individuals who formed this club were inspired in part by the Scotsman James Bruce, who had ventured to Ethiopia in 1769 and reached the source of the Blue Nile.

Overall, the European exploration of Africa in the 17th and 18th centuries was very limited. Instead, they were focused on the slave trade, which only required coastal bases and items to trade. The real exploration of the African interior would start well into the 19th century.

The 19th century

Although the Napoleonic Wars distracted the attention of Europe from exploratory work in Africa, those wars nevertheless exercised great influence on the future of the continent, both in Egypt and South Africa. The occupation of Egypt (1798–1803), first by France and then by Great Britain, resulted in an effort by the Ottoman Empire to regain direct control over that country. In 1811, Mehemet Ali established an almost independent state, and from 1820 onward established Egyptian rule over eastern Sudan. In South Africa, the struggle with Napoleon caused the United Kingdom to take possession of the Dutch settlements at the Cape. In 1814, Cape Colony, which had been continuously occupied by British troops since 1806, was formally ceded to the British crown.

Meanwhile, considerable changes had been made in other parts of the continent. The occupation of Algiers by France in 1830 put an end to the piracy of the Barbary states. Egyptian authority continued to expand southward, with the consequent additions to knowledge of the Nile. The city of Zanzibar, on the island of that name, rapidly attained importance. Accounts of a vast inland sea, and the discovery of the snow-clad mountains of Kilimanjaro in 1840–1848, stimulated the desire for further knowledge about Africa in Europe.

In the mid-19th century, Protestant missions were carrying on active missionary work on the Guinea coast, in South Africa and in the Zanzibar dominions. Missionaries visited little-known regions and peoples, and in many instances became explorers and pioneers of trade and empire. David Livingstone, a Scottish missionary, had been engaged since 1840 in work north of the Orange River. In 1849, Livingstone crossed the Kalahari Desert from south to north and reached Lake Ngami. Between 1851 and 1856, he traversed the continent from west to east, discovering the great waterways of the upper Zambezi River. In November 1855, Livingstone became the first European to see the famous Victoria Falls, named after the Queen of the United Kingdom. From 1858 to 1864, the lower Zambezi, the Shire River and Lake Nyasa were explored by Livingstone. Nyasa had been first reached by the confidential slave of António da Silva Porto, a Portuguese trader established at Bié in Angola, who crossed Africa during 1853–1856 from Benguella to the mouth of the Rovuma. A prime goal for explorers was to locate the source of the River Nile. Expeditions by Burton and Speke (1857–1858) and Speke and Grant (1863) located Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria. It was eventually proved to be the latter from which the Nile flowed.

Henry Morton Stanley, who had in 1871 succeeded in finding and succouring Livingstone (originating the famous line "Dr. Livingstone, I presume"), started again for Zanzibar in 1874. In one of the most memorable of all exploring expeditions in Africa, Stanley circumnavigated Victoria Nyanza (Lake Victoria) and Lake Tanganyika. Striking farther inland to the Lualaba, he followed that river down to the Atlantic Ocean—which he reached in August 1877—and proved it to be the Congo.

In 1895, the British South Africa Company hired the American scout Frederick Russell Burnham to look for minerals and ways to improve river navigation in the central and southern Africa region. Burnham oversaw and led the Northern Territories British South Africa Exploration Company expedition that first established that major copper deposits existed north of the Zambezi in North-Eastern Rhodesia. Along the Kafue River, Burnham saw many similarities to copper deposits he had worked in the United States, and he encountered native peoples wearing copper bracelets.[8] Copper rapidly became the primary export of Central Africa and it remains essential to the economy even today.

Explorers were also active in other parts of the continent. Southern Morocco, the Sahara and the Sudan were traversed in many directions between 1860 and 1875 by Georg Schweinfurth and Gustav Nachtigal.[9] These travellers not only added considerably to geographical knowledge, but obtained invaluable information concerning the people, languages and natural history of the countries in which they sojourned. Among the discoveries of Schweinfurth was one that confirmed Greek legends of the existence beyond Egypt of a "pygmy race". But the first western discoverer of the pygmies of Central Africa was Paul Du Chaillu, who found them in the Ogowe district of the west coast in 1865, five years before Schweinfurth's first meeting with them. Du Chaillu had previously, through journeys in the Gabon region between 1855 and 1859, made popular in Europe the knowledge of the existence of the gorilla, whose existence was thought to be as legendary as that of the Pygmies of Aristotle.

List of Africa explorers

15th century

15th/16th century

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

16th century

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

18th century

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

19th century

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Early 20th century

References

- Alan B. Lloyd, Herodotus, Book II (1975, 1988 Leiden). Lloyd, Alan B. (1977). "Necho and the Red Sea: Some Considerations". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 63: 142–155. JSTOR 3856314. Alan Lloyd suggests that the Greeks at this time understood that anyone going south far enough and then turning west would have the sun on their right but found it unbelievable that Africa reached so far south. He suggests that "It is extremely unlikely that an Egyptian king would, or could, have acted as Necho is depicted as doing" and that the story might have been triggered by the failure of Sataspes attempt to circumnavigate Africa under Xerxes the Great. See also Jona Lendering, The circumnavigation of Africa, Livius.

- The Periplus of Hanno; a voyage of discovery down the west African coast (1912)

- Harden, Donald (1971) [1962]. The Phoenicians. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-021375-9.

- "Some taking Hanno to the Cameroons, or even Gabon, while others say he stopped at Sierre Leone." (Harden 1971, p. 169).

- R.C.C. Law (1979). "North Africa in the period of Phoenician and Greek colonization". In Fage, J.D. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 9780521215923. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- The limit of Ptolemy's knowledge in the west is Cape Spartel (35° 48′ N); while he does assume that the coast eventually retreats in a "Great Gulf of the Western Ocean", this is not likely based on any knowledge of the Gulf of Guinea. Eric Anderson Walker, The Cambridge history of the British Empire, Volume 7, Part 1, 1963, p. 66. In the east, Ptolemy is aware of the Red Sea (Sinus Arabicus) and the protrusion of the Horn of Africa, describing the gulf south of the Horn of Africa as Sinus Barbaricus.

- Astengo C, Balla M., Brigati I., Ferrada de Noli M., Gomes L., Hall T., Pires V., Rosetti C. Da Noli a Capo Verde. Antonio de Noli e l'inizio delle scoperte del Nuovo Mondo. Marco Sabatelli Editore. Savona, 2013. ISBN 9788888449821 [4]

- Burnham, Frederick Russell (1899). "Northern Rhodesia". In Wills, Walter H. (ed.). . Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. pp. 177–180.

- "Sahara and Sudan: The Results of Six Years Travel in Africa". World Digital Library. 1879–1889. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- http://www.rhodesia.nl/rhodesiana/volume19.pdf

Bibliography

- Michael Crowder, The Story of Nigeria, Faber and Faber, London, 1978 (1962)

- Basil Davidson, The African Past, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1966 (1964)

- Donald Harden, The Phoenicians, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1971 (1962)

- Herodotus, transl. Aubrey de Selincourt, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1968 (1954)

- Historia Universal Siglo XXI. Africa: desde la prehistoria hasta los años sesenta. Pierre Bertaux, 1972. Siglo XXI Editores S.A. ISBN 84-323-0069-1

- Vincent B. Khapoya, The African Experience, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 1998 (1994)

- Louise Levanthes, When China Ruled the Seas, Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford, 1994

- Kevin Shillington, History of Africa, St Martin's Press, New York, 1995 (1989)