Wa (Japan)

Wa (倭, "Japan, Japanese", from Chinese 倭; Middle Chinese hwa) is the oldest recorded name of Japan. The Chinese as well as Korean and Japanese scribes regularly wrote it in reference to Yamato (ancient Japanese nation) with the Chinese character 倭 "submissive, distant, dwarf", until the 8th century, when the Japanese replaced it with 和 "harmony, peace, balance".

.png)

| Wa | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 倭 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | submissive, distant, dwarf | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 和 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | harmony | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 倭 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Historical references

The earliest textual references to Japan are in Chinese classic texts. Within the official Chinese dynastic Twenty-Four Histories, Japan is mentioned among the so-called Dongyi 東夷 "Eastern Barbarians".

The historian Wang Zhenping summarizes Wo contacts with the Han State.

When chieftains of various Wo tribes contacted authorities at Lelang, a Chinese commandery established in northern Korea in 108 B.C. by the Western Han court, they sought to benefit themselves by initiating contact. In A.D. 57, the first Wo ambassador arrived at the capital of the Eastern Han court (25-220); the second came in 107.

Wo diplomats, however, never called on China on a regular basis. A chronology of Japan-China relations from the first to the ninth centuries reveals this irregularity in the visits of Japanese ambassadors to China. There were periods of frequent contacts as well as of lengthy intervals between contacts. This irregularity clearly indicated that, in its diplomacy with China, Japan set its own agenda and acted on self-interest to satisfy its own needs.

No Wo ambassador, for example, came to China during the second century. This interval continued well past the third century. Then within merely nine years, the female Wo ruler Himiko sent four ambassadors to the Wei court (220-265) in 238, 243, 245, and 247 respectively. After the death of Himiko, diplomatic contacts with China slowed. Iyoo, the female successor to Himiko, contacted the Wei court only once. The fourth century was another quiet period in China-Wo relations except for the Wo delegation dispatched to the Western Jin court (265-316) in 306. With the arrival of a Wo ambassador at the Eastern Jin court (317-420) in 413, a new age of frequent diplomatic contacts with China began. Over the next sixty years, ten Wo ambassadors called on the Southern Song court (420-479), and a Wo delegation also visited the Southern Qi court (479-502) in 479. The sixth century, however, saw only one Wo ambassador pay respect to the Southern Liang court (502-557) in 502. When these ambassadors arrived in China, they acquired official titles, bronze mirrors, and military banners, which their masters could use to bolster their claims to political supremacy, to build a military system, and to exert influence on southern Korea. (Wang 2005:221-222)

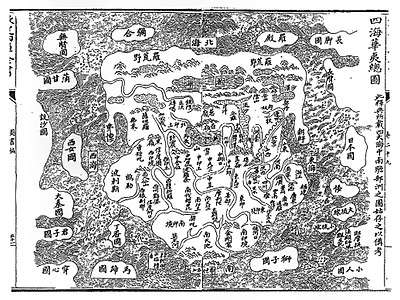

Shan Hai Jing

Possibly the earliest record of Wō 倭 "Japan" occurs in the Shan Hai Jing 山海經 "Classic of Mountains and Seas". The textual dating of this collection of geographic and mythological legends is uncertain, but estimates range from 300 BCE to 250 CE. The Haineibei jing 海內北經 "Classic of Regions within the North Seas" chapter includes Wō 倭 "Japan" among foreign places both real, such as Korea, and legendary (e.g. Penglai Mountain).

Kai [cover] Land is south of Chü Yen and north of Wo. Wo belongs to Yen. [蓋國在鉅燕南倭北倭屬燕 朝鮮在列陽東海北山南列陽屬燕] Ch’ao-hsien [Chosŏn, Korea] is east of Lieh Yang, south of Hai Pei [sea north] Mountain. Lieh Yang belongs to Yen. (12, tr. Nakagawa 2003:49)

Nakagawa notes that Zhuyan 鉅燕 refers to the (ca. 1000-222 BCE) kingdom of Yan (state), and that Wo ("Japan was first known by this name.") maintained a "possible tributary relationship" with Yan.

Lunheng

Wang Chong's ca. 70-80 CE Lunheng 論衡 "Discourses weighed in the balance" is a compendium of essays on subjects including philosophy, religion, and natural sciences.

The Rŭzēng 儒増 "Exaggerations of the Literati" chapter mentions Wōrén 倭人 "Japanese people" and Yuèshāng 越裳 "an old name for Champa" presenting tributes during the Zhou Dynasty. In disputing legends that ancient Zhou bronze ding tripods had magic powers to ward off evil spirits, Wang says.

During the Chou time there was universal peace. The Yuèshāng offered white pheasants to the court, the Japanese odoriferous plants. [獻白雉倭人貢鬯草] Since by eating these white pheasants or odoriferous plants one cannot keep free from evil influences, why should vessels like bronze tripods have such a power? (26, tr. Forke 1907:505)

Another Lunheng chapter Huiguo 恢國 "Restoring the nation" similarly records that Emperor Cheng of Han (r. 51-7 BCE) was presented tributes of Vietnamese pheasants and Japanese herbs (58, tr. Forke 1907:208).

Han Shu

The ca. 82 CE Han Shu 漢書 "Book of Han"' covers the Former Han Dynasty (206 BCE-24 CE) period. Near the conclusion of the Yan entry in the Dilizhi 地理志 "Treatise on geography" section, it records that Wo encompassed over 100 guó 國 "communities, nations, countries".

Beyond Lo-lang in the sea, there are the people of Wo. They comprise more than one hundred communities. [樂浪海中有倭人分爲百餘國] It is reported that they have maintained intercourse with China through tributaries and envoys. (28B, tr. Otake Takeo 小竹武夫, cited by Nakagawa 2003:50)

Emperor Wu of Han established this Korean Lelang Commandery in 108 BCE. Historian Endymion Wilkinson (2000:726) says Wo 倭 "dwarf" was used originally in the Hanshu, "probably to refer to the inhabitants of Kyushu and the Korean peninsula. Thereafter to the inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago."

Wei Zhi

%2C_297.jpg)

The ca. 297 CE Wei Zhi 魏志 "Records of Wei", comprising the first of the San Guo Zhi 三國志 "Records of the Three Kingdoms", covers history of the Cao Wei kingdom (220-265 CE). The 東夷伝 "Encounters with Eastern Barbarians" section describes the Wōrén 倭人 "Japanese" based upon detailed reports from Chinese envoys to Japan. It contains the first records of Yamatai-koku, shamaness Queen Himiko, and other Japanese historical topics.

The people of Wa dwell in the middle of the ocean on the mountainous islands southeast of [the prefecture] of Tai-fang. They formerly comprised more than one hundred communities. During the Han dynasty, [Wa envoys] appeared at the Court; today, thirty of their communities maintain intercourse [with us] through envoys and scribes. [倭人在帯方東南大海之中依山爲國邑舊百餘國漢時有朝見者今使早譯所通三十國] (tr. Tsunoda 1951:8)

This Wei Zhi context describes sailing from Korea to Wa and around the Japanese archipelago. For instance,

A hundred li to the south, one reaches the country of Nu [奴國], the official of which is called shimako, his assistant being termed hinumori. Here there are more than twenty thousand households. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:0)

Tsunoda (1951:5) suggests this ancient Núguó 奴國 (lit. "slave country"), Japanese Nakoku 奴国, was located near present-day Hakata in Kyūshū.

Some 12,000 li to the south of Wa is Gǒunúguó 狗奴國 (lit. "dog slave country"), Japanese Kunakoku, which is identified with the Kumaso tribe that lived around Higo and Ōsumi Provinces in southern Kyūshū. Beyond that,

Over one thousand li to the east of the Queen's land, there are more countries of the same race as the people of Wa. To the south, also there is the island of the dwarfs [侏儒國] where the people are three or four feet tall. This is over four thousand li distant from the Queen's land. Then there is the land of the naked men, as well of the black-teethed people. [裸國黒齒國] These places can be reached by boat if one travels southeast for a year. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:13)

One Wei Zhi passage (tr. Tsunoda 1951:14) records that in 238 CE the Queen of Wa sent officials with tribute to the Wei emperor Cao Rui, who reciprocated with lavish gifts including a gold seal with the official title "Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei".

Another passage relates Wa tattooing with legendary King Shao Kang of the Xia Dynasty.

Men great and small, all tattoo their faces and decorate their bodies with designs. From olden times envoys who visited the Chinese Court called themselves "grandees" [大夫]. A son of the ruler Shao-k'ang of Hsia, when he was enfeoffed as lord of K'uai-chi, cut his hair and decorated his body with designs in order to avoid the attack of serpents and dragons. The Wa, who are fond of diving into the water to get fish and shells, also decorated their bodies in order to keep away large fish and waterfowl. Later, however, the designs became merely ornamental. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:10)

"Grandees" translates Chinese dàfū 大夫 (lit. "great man") "senior official; statesman" (cf. modern dàifu 大夫 "physician; doctor"), which mistranslates Japanese imperial taifu 大夫 "5th-rank courtier; head of administrative department; grand tutor" (the Nihongi records that the envoy Imoko was a taifu).

A second Wei history, the ca. 239-265 CE Weilüe 魏略 "Brief account of the Wei dynasty" is no longer extant, but some sections (including descriptions of the Roman Empire) are quoted in the 429 CE San Guo Zhi commentary by Pei Songzhi 裴松之. He quotes the Weilüe that "Wō people call themselves posterity of Tàibó" (倭人自謂太伯之後). Taibo was the uncle of King Wen of Zhou, who ceded the throne to his nephew and founded the ancient state of Wu (585-473 BCE). The Records of the Grand Historian has a section titled 吳太伯世家 "Wu Taibo's Noble Family", and his shrine is located in present day Wuxi. Researchers have noted cultural similarities between the ancient Wu state and Wō Japan including ritual tooth-pulling, back child carriers, and tattooing (represented with red paint on Japanese Haniwa statues).

Hou Han Shu

The ca. 432 CE Hou Han Shu 後漢書 "Book of Later/Eastern Han" covers the Later Han Dynasty (25-220 CE) period, but was not compiled until two centuries later. The Wōrén 倭人 "Japanese" are included under the 東夷伝 "Encounters with Eastern Barbarians" section.

The Wa dwell on mountainous islands southeast of Tai-fang in the middle of the ocean, forming more than one hundred communities [倭人在帯方東南大海之中依山爲國邑舊百餘國]. From the time of the overthrow of Chao-hsien [northern Korea] by Emperor Wu (B.C. 140-87), nearly thirty of these communities have held intercourse with the Han [dynasty] court by envoys or scribes. Each community has its king, whose office is hereditary. The King of Great Wa resides in the country of Yamadai [邪馬台国]. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:1)

Comparing the opening descriptions of Wa in the Wei Zhi and Hou Han Shu clearly reveals that the latter is derivative. Their respective accounts of the dwarf, naked, and black-teethed peoples provide another example of copying.

Leaving the queen's land and crossing the sea to the east, after a voyage of one thousand li, the country of Kunu [狗奴國] is reached, the people of which are of the same race as that of the Wa. They are not the queen's subjects, however. Four thousand li away to the south of the queen's land, the dwarf's country [侏儒國] is reached; its inhabitants are three to four feet in height. After a year's voyage by ship to the southeast of the dwarf's country, one comes to the land of naked men and also to the country of black-teethed people [裸國黑齒國]; here our communication service ends. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:3)

This Hou Han Shu account of Japan contains some historical details not found in the Wei Zhi.

In … [57 CE], the Wa country Nu [倭奴國] sent an envoy with tribute who called himself ta-fu [大夫]. This country is located in the southern extremity of the Wa country. Kuang-wu bestowed on him a seal. In … [107 CE], during the reign of An-ti (107-125), the King of Wa presented one hundred sixty slaves, making at the same time a request for an imperial audience. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:2)

Tsunoda (1951:5) notes support for the Hakata location of Nu/Na country in the 1784 discovery at Hakata Bay of a gold seal bearing the inscription 漢委奴國王, usually translated "Han [vassal?] King of the Wa country Nu." Although the name of the King of Wa in AD 107 does not appear in the above translation, his name is Suishō (帥升) according to the original text.

Song Shu

The 488 CE Song Shu 宋書 "Book of Song" covers the brief history of the Liu Song Dynasty (420-479). Under the "Eastern and Southern Barbarians" 夷蠻 section, Japan is called Wōguó 倭國, Japanese Wakoku, and said to be located off Goguryeo. In contrast with the earlier histories that describe the Wa as a 人 "people", this Song history describes them as a 國 "country".

The country of Wa is in the midst of the great ocean, southeast of Koguryŏ. From generation to generation, [the Wa people] carry out their duty of bringing tribute. [倭國在高驪東南大海中世修貢職] In … [421], the first Emperor said in a rescript: "Ts'an [讚, Emperor Nintoku (r. ca. 313-319)] of Wa sends tribute from a distance of tens of thousands of li. The fact that he is loyal, though so far away, deserves appreciation. Let him, therefore, be granted rank and title." … When Ts'an died and his brother, Chen [珍, Emperor Hanzei (r. ca. 406-411)], came to the throne, the latter sent an envoy to the Court with tribute. Signing himself as King of Wa and General Who Maintains Peace in the East [安東大將軍倭王] Commanding with Battle-Ax All Military Affairs in the Six Countries of Wa, Paekche, Silla, Imna, Chin-han and Mok-han, he presented a memorial requesting that his titles be formally confirmed. An imperial edict confirmed his title of King of Wa and General Who Maintains Peace in the East. … In the twentieth year [443], Sai [濟, Emperor Ingyō (r. ca. 412-453)], King of Wa, sent an envoy with tribute and was again confirmed as King of Wa and General Who Maintains Peace. In the twenty-eighth year [451], the additional title was granted of General Who Maintains Peace in the East Commanding with Battle-Ax All Military Affairs in the Six Countries of Wa, Silla, Imna, Kala, Chin-han and Mok-han. (99, tr. Tsunoda 1951:22-23)

The Song Shu gives detailed accounts of relations with Japan, indicating that the Wa kings valued their political legitimization from the Chinese emperors.

Liang Shu

The 635 CE Liang Shu 梁書 "Book of Liang", which covers history of the Liang Dynasty (502-557), records the Buddhist monk Hui Shen's trip to Wa and the legendary Fusang. It refers to Japan as Wō 倭 (without "people" or "country" suffixation) under the Dongyi "Eastern Barbarians" section, and begins with the Taibo legend.

The Wa say of themselves that they are posterity of Tàibó. According to custom, the people are all tattooed. Their territory is over 12,000 li from Daifang. It is located approximately east of Kuaiji [on Hangzhou Bay], though at an extremely great distance. [倭者自云太伯之後俗皆文身去帶方萬二千餘里大抵在會稽之東相去絶遠]

Later texts repeat this myth of Japanese descent from Taibo. The 648 CE Jin Shu 晉書 "Book of Jin" about the Jin Dynasty (265-420 CE) uses a different "call" verb, wèi 謂 "say; call; name" instead of yún 云 "say; speak; call", "They call themselves the posterity of Tàibó [自謂太伯之後]". The 1084 CE Chinese universal history Zizhi Tongjian 資治通鑑 speculates, "The present-day Japan is also said to be posterity of Tàibó of Wu; perhaps when Wu was destroyed, [a member of] a collateral branch of the royal family disappeared at sea and became Wo." [今日本又云吳太伯之後蓋吳亡其支庶入海為倭].

Sui Shu

The 636 CE Sui Shu 隋書 "Book of Sui" records the history of the Sui Dynasty (581-618) when China was reunified. Wōguó/Wakoku is entered under "Eastern Barbarians", and said to be located off of Baekje and Silla (see Hogong), two of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.

Wa-kuo is situated in the middle of the great ocean southeast of Paekche and Silla, three thousand li away by water and land. The people dwell on mountainous islands. [倭國在百濟新羅東南水陸三千里於大海之中依山島而居] During the Wei dynasty, over thirty countries [of Wa-kuo], each of which boasted a king, held intercourse with China. These barbarians do not know how to measure distance by li and estimate it by days. Their domain is five months' journey from east to west, and three months' from north to south; and the sea lies on all sides. The land is high in the east and low in the west. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:28)

In 607 CE, the Sui Shu records that "King Tarishihoko" (a mistake for Empress Suiko) sent an envoy, Buddhist monks, and tribute to Emperor Yang. Her official message is quoted using the word Tiānzǐ 天子 "Son of Heaven; Chinese Emperor".

"The Son of Heaven in the land where the sun rises addresses a letter to the Son of Heaven in the land where the sun sets. We hope you are in good health." When the Emperor saw this letter, he was displeased and told the chief official of foreign affairs that this letter from the barbarians was discourteous, and that such a letter should not again be brought to his attention. (tr. Tsunoda 1951:32)

In 608, the Emperor dispatched Pei Ching as envoy to Wa, and he returned with a Japanese delegation.

The Japanese Nihongi (22, tr. Aston 1972 2:136-9) also records these imperial envoys of 607 and 608, but with a differing Sino-Japanese historical perspective. It records more details, such as naming the envoy Imoko Wono no Omi and translator Kuratsukuri no Fukuri, but not the offensive Chinese translation. According to the Nihongi, when Imoko returned from China, he apologized to Suiko for losing Yang's letter because Korean men "searched me and took it from me." When the Empress received Pei, he presented a proclamation (tr. Aston 1972 2:137-8) contrasting Chinese Huángdì 皇帝 "Emperor" with Wōwáng 倭王 "Wa King", "The Emperor [皇帝] greets the Sovereign of Wa [倭王]." According to the Nihongi, Suiko gave Pei a different version of the imperial letter, contrasting Japanese Tennō 天皇 "Japanese Emperor" and Kōtei 皇帝 "Emperor" (Chinese tiānhuáng and huángdì) instead of using "Son of Heaven".

The Emperor [天皇] of the East respectfully addresses the Emperor [皇帝] of the West. Your Envoy, P'ei Shih-ch'ing, Official Entertainer of the Department of foreign receptions, and his suite, having arrived here, my long-harbored cares were dissolved. This last month of autumn is somewhat chilly. How is Your Majesty? We trust well. We are in our usual health. (tr. Aston 1972 2:139)

Aston quotes the 797 CE Shoku Nihongi history that this 607 Japanese mission to China first objected to writing Wa with the Chinese character 倭.

"Wono no Imoko, the Envoy who visited China, (proposed to) alter this term into Nippon, but the Sui Emperor ignored his reasons and would not allow it. The term Nippon was first used in the period … 618-626." Another Chinese authority gives 670 as the date when Nippon began to be officially used in China. (1972 2:137-8)

Tang Shu

The custom of writing "Japan" as Wa 倭 ended during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE). Japanese scribes coined the name Nihon or Nippon 日本 circa 608–645 and replaced Wa 倭 with a more flattering Wa 和 "harmony; peace" around 756–757 CE (Carr 1992:6-7). The linguistic change is recorded in two official Tang histories.

The 945 CE Tang shu "Book of Tang" 唐書 (199A) has the oldest Chinese reference to Rìběn 日本. The "Eastern Barbarian" section lists both Wakoku 倭国 and Nipponkoku 日本国, giving three explanations: Nippon is an alternate name for Wa, or the Japanese disliked Wakoku because it was "inelegant; coarse" 不雅, or Nippon was once a small part of the old Wakoku.

The 1050 CE Xin Tang Shu 新唐書 "New Book of Tang", which has a Riben 日本 heading for Japan under the "Eastern Barbarians", gives more details.

Japan in former times was called Wa-nu. It is 14,000 li distant from our capital, situated to the southeast of Silla in the middle of the ocean. It is five months' journey to cross Japan from east to west, and a three-month journey from south to north. [日本古倭奴也去京師萬四千里直新羅東南在海中島而居東西五月行南北三月行] (145, tr. Tsunoda 1951:38)

Regarding the change in autonyms, the Xin Tang Shu says.

In … 670, an embassy came to the Court [from Japan] to offer congratulations on the conquest of Koguryŏ. Around this time, the Japanese who had studied Chinese came to dislike the name Wa and changed it to Nippon. According to the words of the (Japanese) envoy himself, that name was chosen because the country was so close to where the sun rises. [後稍習夏音惡倭名更號日本使者自言國近日所出以為名] Some say, (on the other hand), that Japan was a small country which had been subjugated by the Wa, and that the latter took over its name. As this envoy was not truthful, doubt still remains. [或雲日本乃小國為倭所並故冒其號使者不以情故疑焉] [The envoy] was, besides, boastful, and he said that the domains of his country were many thousands of square li and extended to the ocean on the south and on the west. In the northeast, he said, the country was bordered by mountain ranges beyond which lay the land of the hairy men. (145, tr. Tsunoda 1951:40)

Subsequent Chinese histories refer to Japan as Rìběn 日本 and only mention Wō 倭 as an old name.

Gwanggaeto Stele

The earliest Korean reference to Japanese Wa (Wae in Korean) is the 414 CE Gwanggaeto Stele that was erected to honor King Gwanggaeto the Great of Goguryeo (r. 391-413 CE). This memorial stele, which has the oldest usage of Wakō (倭寇, "Japanese pirates", Waegu in Korean), records Wa as a military ally of Baekje in their battles with Goguryeo and Silla. Some scholars interpret these references to mean not only "Japanese" but also "Gaya peoples" in the southern Korean Peninsula. For instance, Lee suggests,

If Kokuryo could not destroy Paekche itself, it wished for someone else to do so. Thus, in another sense, the inscription may have been wishful thinking. At any rate, Wae denoted both the southern Koreans and people who lived on the southwest Japanese islands, the same Kaya people who had ruled both regions in ancient times. Wae did not denote Japan alone, as was the case later. (1997:34)

"It is generally thought that these Wae were from the archipelago," write Lewis and Sesay (2002:104), "but we as yet have no conclusive evidence concerning their origins."

The word Wa

The Japanese endonym Wa 倭 "Japan" derives from the Chinese exonym Wō 倭 "Japan, Japanese", a graphic pejorative Chinese character that had some offensive connotation, possibly "submissive, docile, obedient", "bowing; bent over", or "short person; dwarf".

倭 and 和 characters

The Chinese character 倭 combines the 人 or 亻 "human, person" radical and a wěi 委 "bend" phonetic. This wěi phonetic element depicts hé 禾 "grain" over nǚ 女 "woman", which Bernhard Karlgren (1923:368) semantically analyzes as: "bend down, bent, tortuous, crooked; fall down, throw down, throw away, send away, reject; send out, delegate – to bend like a 女 woman working with the 禾 grain." The oldest written forms of 倭 are in Seal script, and it has not been identified in Bronzeware script or Oracle bone script.

Most characters written with this wěi 委 phonetic are pronounced wei in Standard Chinese:

- wèi 魏 ("ghost" radical) "the state of Wei"

- wēi 逶 ("motion" radical) "serpentine; winding, curving" [in wēiyí 逶迤 "winding (road, river)"]

- wěi 萎 ("plant" radical) "wilt; wither; atrophy; tire, grow weary; (metaphorically) decline, fade"

- wěi 痿 ("sickness" radical) "paralysis; impotence"

- wěi 諉 ("speech" radical) "shirk; shift blame (onto others)"

- wèi 餧 ("food" radical) "feed (animals)"

The unusual Wō 倭 "Japan" pronunciation of the wěi 委 phonetic element is also present in:

- wō 踒 ("foot" radical) "strain; sprain (sinew or muscle)"

- wǒ 婑 ("woman" radical) "beautiful" [in wǒtuǒ 婑媠 "beautiful; pretty"]

A third pronunciation is found in the reading of the following character:

- ǎi 矮 ("arrow" radical) "dwarf, short of stature; low; inferior"

Nara period Japanese scholars believed that Chinese character for Wō 倭 "Japan", which they used to write "Wa" or "Yamato", was graphically pejorative in denoting 委 "bent down" 亻 "people". Around 757 CE, Japan officially changed its endonym from Wa 倭 to Wa 和 "harmony; peace; sum; total". This replacement Chinese character hé 和 combines a hé 禾 "grain" phonetic (also seen in 倭) and the "mouth" radical 口. Carr explains:

Graphic replacement of the 倭 "dwarf Japanese" Chinese logograph became inevitable. Not long after the Japanese began using 倭 to write Wa ∼ Yamato 'Japan', they realized its 'dwarf; bent back' connotation. In a sense, they had been tricked by Chinese logography; the only written name for 'Japan' was deprecating. The chosen replacement wa 和 'harmony; peace' had the same Japanese wa pronunciation as 倭 'dwarf', and - most importantly - it was semantically flattering. The notion that Japanese culture is based upon wa 和 'harmony' has become an article of faith among Japanese and Japanologists. (1992:6)

In current Japanese usage, Wa 倭 "old name for Japan" is a variant Chinese character for Wa 和 "Japan", excepting a few historical terms like the Five kings of Wa, wakō (Chinese Wōkòu 倭寇 "Japanese pirates"), and Wamyō Ruijushō dictionary. In marked contrast, Wa 和 is a common adjective in Sino-Japanese compounds like Washoku 和食 "Japanese cuisine", Wafuku 和服 "Japanese clothing", Washitsu 和室 "Japanese-style room", Waka 和歌 "Japanese-style poetry", Washi 和紙 "traditional Japanese paper", Wagyu 和牛 "Japanese cattle".

Pronunciations

| Wa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 倭 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 왜 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ワ (On) やまと (Kun) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In Chinese, the character 倭 can be pronounced wēi "winding", wǒ "an ancient hairstyle", or Wō "Japan". The first two pronunciations are restricted to Classical Chinese bisyllabic words. Wēi 倭 occurs in wēichí 倭遲 "winding; sinuous; circuitous; meandering", which has numerous variants including wēiyí 逶迤 and 委蛇. The oldest recorded usage of 倭 is the Shi Jing (162) description of a wēichí 倭遲 "winding; serpentine; tortuous" road; compare (18) using wēituó 委佗 "compliant; bending, pliable; graceful". Wǒ 倭 occurs in wǒduòjì 倭墮髻 "a woman's hairstyle with a bun, popular during the Han Dynasty". The third pronunciation Wō 倭 "Japan; Japanese" is more productive than the first two, as evident in Chinese names for "Japanese" things (e.g., Wōkòu 倭寇 "Japanese pirates" above) or "dwarf; pygmy" animals.

- wōqī 倭漆 "Japanese lacquerware"

- wōdāo 倭刀 "Japanese sword"

- wōguā 倭瓜 (lit. "Japanese melon") "pumpkin; squash"

- wōhémǎ 倭河馬 "pygmy hippopotamus"

- wōzhū 倭豬 "pygmy hog"

- wōhúhóu 倭狐猴 "dwarf lemur"

- wōheixingxing 倭黑猩猩 "pygmy chimpanzee"

Reconstructed pronunciations of wō 倭 in Middle Chinese (ca. 6th-10th centuries CE) include ʼuâ (Bernhard Karlgren), ʼua (Zhou Fagao), and ʼwa (Edwin G. Pulleyblank). Reconstructions in Old Chinese (ca. 6th-3rd centuries BCE) include *ʼwâ (Karlgren), *ʼwər (Dong Tonghe), and *ʼwər (Zhou).

In Japanese, the Chinese character 倭 has Sinitic on'yomi pronunciations of wa or ka from Chinese wō "Japan" and wǒ "an ancient hairstyle", or wi or i from wēi "winding; obedient", and native kun'yomi pronunciations of yamato "Japan" or shitagau "obey, obedient". Chinese wō 倭 "an old name for Japan" is a loanword in other East Asian languages including Korean 왜 wae or wa, Cantonese wai1 or wo1, and Taiwanese Hokkien e2.

Etymology

Although the etymological origins of Wa remain uncertain, Chinese historical texts recorded an ancient people residing in the Japanese archipelago (perhaps Kyūshū), named something like *ʼWâ or *ʼWər 倭. Carr (1992:9-10) surveys prevalent proposals for Wa's etymology ranging from feasible (transcribing Japanese first-person pronouns waga 我が "my; our" and ware 我 "I; oneself; thou") to shameful (writing Japanese Wa as 倭 implying "dwarf barbarians"), and summarizes interpretations for *ʼWâ "Japanese" into variations on two etymologies: "behaviorally 'submissive' or physically 'short'."

The first "submissive; obedient" explanation began with the (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi dictionary. It defines 倭 as shùnmào 順皃 "obedient/submissive/docile appearance", graphically explains the "person; human' radical with a wěi 委 "bent" phonetic, and quotes the above Shi Jing poem. According to the (1716) Kangxi Dictionary (倭又人名 魯宣公名倭), 倭 was the name of King Tuyen (魯宣公) of Lu (Chinese: 魯國; pinyin: Lǔ Guó, circa 1042–249 BC). "Conceivably, when Chinese first met Japanese," Carr (1992:9) suggests "they transcribed Wa as *ʼWâ 'bent back' signifying 'compliant' bowing/obeisance. Bowing is noted in early historical references to Japan." Examples include "Respect is shown by squatting" (Hou Han Shu, tr. Tsunoda 1951:2), and "they either squat or kneel, with both hands on the ground. This is the way they show respect." (Wei Zhi, tr. Tsunoda 1951:13). Koji Nakayama (linked below) interprets wēi 逶 "winding" as "very far away" and euphemistically translates Wō 倭 as "separated from the continent."

The second etymology of wō 倭 meaning "dwarf; short person" has possible cognates in ǎi 矮 "short (of stature); midget, dwarf; low", wō 踒 "strain; sprain; bent legs", and wò 臥 "lie down; crouch; sit (animals and birds)". Early Chinese dynastic histories refer to a Zhūrúguó 侏儒國 "pygmy/dwarf country" located south of Japan, associated with possibly Okinawa Island or the Ryukyu Islands. Carr cites the historical precedence of construing Wa as "submissive people" and the "Country of Dwarfs" legend as evidence that the "little people" etymology was a secondary development.

Since early Chinese information about Wo/Wa peoples was based largely on hearsay, Wang Zhenping (2005:9) says, "Little is certain about the Wo except they were obedient and complaisant."

Lexicography

An article by Michael Carr (1992:1) "compares how Oriental and Occidental lexicographers have treated the fact that Japan's first written name was a Chinese Wō < *ʼWâ 倭 'short/submissive people' insult." It evaluates 92 dictionary definitions of Chinese Wō 倭 to illustrate lexicographical problems with defining ethnically offensive words. This corpus of monolingual and bilingual Chinese dictionaries includes 29 Chinese-Chinese, 17 Chinese-English, 13 Chinese to other Western Languages, and 33 Chinese-Japanese dictionaries. To analyze how Chinese dictionaries deal with the belittling origins of Wō, Carr divides definitions into four types, abbreviated with Greek alphabet letters Alpha through Delta.

- Α = "dwarf; Japanese"

- Β = "compliant; Japanese"

- Γ = "derogatory Japanese"

- Δ = "Japanese"

For example, Alpha (A) type includes both overt definitions like "The land of dwarfs; Japan" (Liushi Han-Ying cidian 劉氏漢英辭典 [Liu's Chinese-English Dictionary] 1978) and more sophisticated semantic distinctions like "(1) A dwarf. (2) Formerly, used to refer to Japan" (Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage 1972). Beta (B) "compliant; Japanese" is illustrated by "demütig [humble; submissive; meek], gehorchen [obey; respond]" (Praktisches zeichenlexikon chinesisch-deutsch-japanisch [A Practical Chinese-German-Japanese Character Dictionary] 1983). Gamma (Γ) "type definitions such as "depreciatingly Japanese" (e.g., A Beginner's Chinese-English Dictionary of the National Language (Gwoyeu) 1964) include usage labels such as "derogatory," "disparaging," "offensive," or "contemptuous". Some Γ notations are restricted to subentries like "Wōnú 倭奴 (in modern usage, derogatively) the Japs" (Zuixin shiyong Han-Ying cidian 最新實用和英辭典 [A New Practical Chinese-English Dictionary] 1971). Delta (Δ) "Japanese" is the least informative type of gloss; for instance, "an old name for Japan" (Xin Han-Ying cidian 新漢英詞典 [A New Chinese-English Dictionary] 1979).

Carr evaluates these four typologies for defining the Chinese 倭 "bent people" graphic pejoration.

From a theoretical standpoint, A "dwarf" or B "submissive" type definitions are preferable for providing accurate etymological information, even though it may be deemed offensive. It is no transgression for an abridged Chinese dictionary to give a short Δ "Japan" definition, but adding "an old name for" or "archaic" takes no more space than adding a Γ "derogatory" note. A Δ definition avoids offending the Japanese, but misleads the dictionary user in the same way as the OED2 defining wetback and white trash without usage labels. (1992:12).

The table below (Carr 1992:31, "Table 8. Overall Comparison of Definitions") summarizes how Chinese dictionaries define Wō 倭.

| Definition Type | Chinese–Chinese | Chinese–English | Chinese–Other | Chinese–Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Α "dwarf; Japanese" | 3 (10%) | 10 (59%) | 5 (38%) | 4 (12%) |

| Β "compliant; Japanese" | 0 | 0 | 1 (8%) | 4 (12%) |

| Γ derogatory Japanese | 0 | 1 (6%) | 3 (23%) | 11 (33%) |

| Δ "Japanese" | 26 (90%) | 6 (35%) | 4 (31%) | 14 (42%) |

| Total Dictionaries | 29 | 17 | 13 | 33 |

Half of the Western language dictionaries note that Chinese Wō 倭 "Japanese" means "little person; dwarf", while most Chinese-Chinese definitions overlook the graphic slur with Δ type "ancient name for Japan" definitions. This demeaning A "dwarf" description is found more often in Occidental language dictionaries than in Oriental ones. The historically more accurate, and ethnically less insulting, "subservient; compliant" B type is limited to Chinese-Japanese and Chinese-German dictionaries. The Γ type "derogatory" notation occurs most often among Japanese and European language dictionaries. The least edifying Δ "(old name for) Japan" type definitions are found twice more often in Chinese-Chinese than in Chinese-Japanese dictionaries, and three times more than in Western ones.

Even the modern-day Unicode universal character standard reflects inherent lexicographic problems with this ancient Chinese Wō 倭 "Japan" affront. The Unihan (Unified CJK characters) segment of Unicode largely draws definitions from two online dictionary projects, the Chinese CEDICT and Japanese EDICT. The former lists Chinese wo1 倭 "Japanese; dwarf", wokou4 倭寇 "(in ancient usage) the dwarf-pirates; the Japs", and wonu2 倭奴 "(used in ancient times) the Japanese; (in modern usage, derogatively) the Japs". The latter lists Japanese yamato 倭 "ancient Japan", wajin 倭人 "(an old word for) a Japanese", and wakou 倭寇 "Japanese pirates."

References

- Aston, William G. 1924. Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Charles E. Tuttle reprint 1972.

- Carr, Michael. 1992. "Wa 倭 Wa 和 Lexicography," International Journal of Lexicography 5.1:1-30.

- Forke, Alfred, tr. 1907. Lun-hêng, Part 1, Philosophical Essays of Wang Ch'ung. Otto Harrassowitz.

- Karlgren, Bernhard. 1923. Analytic Dictionary of Chinese and Sino-Japanese. Dover Reprint 1974.

- Lee, Kenneth B. 1997. Korea and East Asia: The Story of a Phoenix. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-95823-X OCLC 35637112.

- Lewis, James B. and Amadu Sesay. 2002. Korea and Globalization: Politics, Economics and Culture. Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1512-6 OCLC 46908525 50074837.

- Nakagawa Masako. 2003. The Shan-hai ching and Wo: A Japanese Connection, Sino-Japanese Studies 15:45-55.

- Tsunoda Ryusaku, tr. 1951. Japan in the Chinese dynastic histories: Later Han through Ming dynasties. Goodrich, Carrington C., ed. South Pasadena: P. D. and Ione Perkins.

- Wang Zhenping. 2005. Ambassadors from the Islands of Immortals: China-Japan Relations in the Han-Tang Period. University of Hawai'i Press.

- Wilkinson, Endymion. 2000. Chinese History: a manual, revised and enlarged ed. Harvard University Asia Center.

External links

| Look up 倭 in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Unihan data for U+502D, Unihan Database entry for 倭

- English translation of the Wei Zhi, Koji Nakayama

- Hong, Wontack (1994). "Queen Himiko as Recorded in the Wei Chronicle. A Protohistoric Yayoi Ruler". Paekche of Korea and the Origin of Yamato Japan (PDF). Seoul: Kudara International. ISBN 978-89-85567-02-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-05.

- The Relatedness between the Origin of Japanese and Korean Ethnicity, Jaehoon Lee

- The Chronicles of Wa, Wesley Injerd

- Japan in Chinese and Japanese Historic Accounts, John A. Tucker

- The Early Relations between China and Japan, Jiang Yike

- (in Japanese) 「三国志・魏志」巻30 東夷伝・倭人, Chinese text and Japanese translation of the Wei Zhi 魏志 account of Wa

- (in Japanese) 邪馬台國研究本編, Chinese text and Japanese translations of Chinese historical accounts of Wa

- (in Japanese) 日本古代史参考史料漢籍, Accounts of Wa from 15 Chinese histories