Vietnamese Americans

Vietnamese Americans (Vietnamese: Người Mỹ gốc Việt) are Americans of full or partial Vietnamese descent.[5] They make up about half of all overseas Vietnamese (Vietnamese: Người Việt hải ngoại) and are the fourth-largest Asian American ethnic group after Chinese Americans, Filipino Americans, and Indian Americans.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,162,610[1] 0.66% of the total U.S. population (2018) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Vietnamese, American English Chinese, French (auxiliary language) | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhist (43%) • Catholic (30%) Unaffiliated (20%) • Protestant (6%)[3][4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Vietnamese people, Overseas Vietnamese, Vietnamese Canadians, Vietnamese Australians, Asian Americans, Chinese Americans, Hmong Americans |

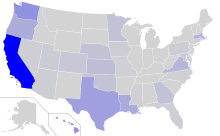

The Vietnamese community in the United States was minimal until the South Vietnamese immigration to the country following the Vietnam War which ended in 1975. Early immigrants were refugee boat people, loyal to South Vietnam in the conflict who fled political persecution or sought economic opportunities. More than half of Vietnamese Americans reside in the two most populous states of California and Texas, primarily their large urban areas.[6]

Demographics

According. to U.S. Census Bureau, the median household income for Vietnamese Americans was $65,643 in 2017.[7] As a relatively-recent immigrant group, most Vietnamese Americans are either first or second generation Americans. As many as one million people five years of age and older speak Vietnamese at home, making it the fifth-most-spoken language in the U.S. In the 2012 American Community Survey (ACS), 76 percent of foreign-born Vietnamese are naturalized U.S. citizens (compared to 67 percent of people from Southeast Asia and 46 percent of the total U.S. foreign-born population). Of those born outside the United States, 73.1 percent entered before 2000, 21.2 percent from 2000 and 2009 and 5.7 percent after 2010.[8]

In 2018, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated the total population of Vietnamese Americans was 2,162,610 (92.1% reporting one race, 7.2% reporting two races, 0.7% reporting three races, and 0.1% reporting four or more races).[7] California and Texas had the highest concentrations of Vietnamese Americans: 40 and 12 percent, respectively. Other states with concentrations of Vietnamese Americans were Washington, Florida (four percent each) and Virginia (three percent).[9] The largest number of Vietnamese outside Vietnam is in Orange County, California (184,153, or 6.1 percent of the county's population),[10] followed by Los Angeles and Santa Clara counties; the three counties accounted for 26 percent of the Vietnamese immigrant population in the United States.[9] Many Vietnamese American businesses exist in the Little Saigon of Westminster and Garden Grove, where Vietnamese Americans make up 40.2 and 27.7 percent of the population respectively. About 41 percent of the Vietnamese immigrant population lives in five major metropolitan areas: in descending order, Los Angeles, San Jose, Houston, San Francisco and Dallas-Fort Worth.[9] The Vietnamese immigration pattern has shifted to other states, including Denver, Boston, Chicago, Oklahoma (Oklahoma City and Tulsa in particular) and Oregon (Portland in particular).

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 261,729 | — |

| 1990 | 614,517 | +134.8% |

| 2000 | 1,122,528 | +82.7% |

| 2010 | 1,548,449 | +37.9% |

Vietnamese Americans are more likely to be Christians than the Vietnamese in Vietnam. Christians (mainly Roman Catholics) make up about six percent of Vietnam's population and about 23 percent of the Vietnamese American population.[11] Due to hostility between Communists and Catholics in Vietnam, many Catholics fled the country after the Communist takeover, and many Catholic Churches had sponsored them to America. [12]

History

The history of Vietnamese Americans is fairly recent. Before 1975, most Vietnamese residing in the US were the wives and children of American servicemen or academics. Records[13][14] indicate that a few Vietnamese (including Ho Chi Minh) arrived and performed menial work during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. According to the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 650 Vietnamese arrived as immigrants between 1950 and 1974, but the figure excludes students, diplomats, and military trainees. The April 30, 1975, fall of Saigon, which ended the Vietnam War, prompted the first large-scale wave of immigration; many with close ties to America or the South Vietnam government feared communist reprisals. Most of the first-wave immigrants were well-educated, financially comfortable, and proficient in English.[15] According to 1975 US State Department data, more than 30 percent of the heads of first-wave households were medical professionals or technical managers, 16.9 percent worked in transportation, and 11.7 percent had clerical or sales jobs in Vietnam. Less than 5 percent were fishermen or farmers.[16]

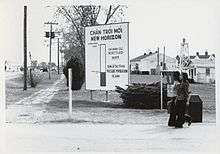

The evacuation of the immigrants was organized in three major ways. The week before Saigon fell, 15,000 people left on scheduled flights followed by an additional 80,000 also evacuated by air. The last group was carried on U.S. Navy ships.[17] During the spring of 1975 125,000 people left South Vietnam, followed by more than 5,000 in 1976–1977.[16] They arrived at reception camps in the Philippines and Guam before being transferred to temporary housing at U.S. military bases, including Camp Pendleton (California), Fort Chaffee (Arkansas), Eglin Air Force Base (Florida) and Fort Indiantown Gap (Pennsylvania). After preparations for resettlement, they were assigned to one of nine voluntary agencies (VOLAGs) to help them find financial and personal support from sponsors in the U.S.[15][17]

South Vietnamese refugees were initially resented by Americans, since the memory of defeat was fresh; according to a 1975 poll, only 36 percent of Americans favored Vietnamese immigration. However, the U.S. government informed public opinion as it felt that it had a moral obligation to the refugees, and President Gerald Ford and Congress both agreed to pass the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act in 1975, which allowed Vietnamese refugees to enter the United States under a special status and allocated $405 million in resettlement aid. To prevent the refugees from forming ethnic enclaves and minimize their impact on local communities, they were distributed throughout the country,[15] but within a few years, many resettled in California and Texas.

_take_Vietnamese_refugees_aboard_a_small..._-_NARA_-_558518.tif.jpg)

A second wave of Vietnamese refugees arrived from 1978 to the mid-1980s. Political and economic instability under the new communist government led to a migration unprecedented in Vietnam. South Vietnamese, particularly former military officers and government employees, were sent to "re-education camps," which were really concentration camps, for intensive political indoctrination. Famine was widespread, and businesses were seized and nationalized. Chinese-Vietnamese relations soured when China became Vietnam's adversary in the brief Sino-Vietnamese War.[15] To escape, many South Vietnamese fled on small, unsafe, crowded fishing boats. Over 70 percent of the first immigrants were from urban areas, but the "boat people" were generally lower socioeconomically, as most were peasant farmers or fishermen, small-town merchants or former military officials. Survivors were picked up by foreign ships and brought to asylum camps in Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Hong Kong, and the Philippines from which they entered countries that agreed to accept them.[15][16][17]

The plight of the boat people compelled the US to act, and the Refugee Act of 1980 eased restrictions on the entry of Vietnamese refugees. From 1978 to 1982, 280,500 Vietnamese refugees were admitted[15] In 1979, the Orderly Departure Program (ODP) was established under the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to allow emigration from Vietnam to the US and other countries. Additional legislation permitted Amerasian children and former political prisoners and their families to enter the US. Vietnamese immigration peaked in 1992, when many re-education-camp inmates were released and sponsored by their families in the US. Between 1981 and 2000, the country accepted 531,310 Vietnamese political refugees and asylum-seekers.

By the early 1980s, a secondary resettlement was underway. Vietnamese refugees were initially scattered throughout the country in wherever they could find sponsorship. The majority (27,199) settled in California, followed by 9,130 in Texas and 3,500 to 7,000 each in Pennsylvania, Florida, Washington, Illinois, New York, and Louisiana. Economic and social factors, many then moved to warmer states, such as California and Texas, with larger Vietnamese communities, better jobs, and social safety nets.[15][16][17]

Though Vietnamese immigration has continued at a fairly steady pace since the 1980s, the pathway to immigration for Vietnamese today has shifted entirely. As opposed to the earlier history of Vietnamese migration that stemmed predominantly from refugees, an overwhelming majority of Vietnamese are now granted lawful permanent residence (LPR) on the basis of family sponsored preferences or by way of immediate relatives to U.S. citizens, at 53% and 44% respectively. This marks a complete about face, in 1982, 99% of Vietnamese that were granted LPR were refugees, while today that group compromises a mere 1% of the Vietnamese population.[9]

Initial challenges

Language barrier

After suffering war and psychological trauma, Vietnamese immigrants had to adapt to a very different culture. Language was the first barrier Vietnamese refugees with limited English proficiency had to overcome. English uses tonal inflection sparingly (primarily for questions); Vietnamese, a tonal language, uses variations in tone to differentiate between meanings of a sound. Ma can have one of six meanings, depending on tone: "ghost", "but", "code", "rice plant", "cheek" or "tomb".[15] Another difference between Vietnamese and English is the former's widespread use of status-related pronouns. "You" is the only second-person singular pronoun in English, but the Vietnamese second-person singular pronoun varies by gender (anh or chị), social status (ông or bà) and relationship (bạn, cậu or mày).[16]

Family issues

Like other Asians, the Vietnamese emphasize parental status; however, American culture challenges this traditional value. Vietnamese American parents have expressed concern about decreasing authority over their children. Part of this concern is due to cultural differences; although corporal punishment is accepted in Vietnamese society as an effective way of educating children.[15] Older, newly arrived Vietnamese Americans are polite in dealing with others and avoid expressing open disagreement; young Vietnamese-American straightforwardness of expression may be perceived as disrespectful by their elders.[16]

Mental health

Emotional health was considered an issue common to many Vietnamese refugees, with war-related loss and the stress of adapting to a different culture leading to mental-health problems among refugees.[15] The problems covered a broad spectrum, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression, adjustment disorder, somatization, panic attacks, schizophrenia and generalized anxiety. About 40 percent of the children of resettled refugees experienced an increase in conduct and oppositional defiant disorders. A 2000 study by Chung et al. demonstrated a number of mental-health issues. The study examined the psychosocial adjustment of two groups of Vietnamese refugees who migrated to the U.S. as young children. Its participants were given the Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale, the Social Support Questionnaire and the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist. The three surveys accounted for cultural assimilation; how closely an individual related to their culture of origin relative to American culture, and individual placement on scales for generalized anxiety and depression respectively. Chung separated the groups into first- and second-wave refugees; first-wave Southeast Asian refugees (SEAR) were defined as arriving in the U.S. between 1971 and 1975, and second-wave SEAR arrived between 1980 and 1985. In wave two, six percent of those tested by Chung et al. were under age six when they arrived in the U.S.; in wave one, about 85 percent of the pediatric refugees were under six. The study indicated that the young refugees experienced significant short- and long-term emotional and mental distress throughout their lives.[18]

Employment

Vietnamese Americans' income and social classes are diverse. In contrast to Vietnamese refugees who settled in France or Germany, and similar to their counterparts who arrived in Canada, The Czech Republic, The United Kingdom and Australia, refugees arriving in the United States often had a lower socioeconomic standing in their home country and more difficulty integrating due to greater linguistic and cultural barriers.

Vietnamese Americans have arrived in the U.S. primarily as refugees, with little or no money. While not as academically or financially accomplished collectively as their East Asian counterparts, census data indicates that Vietnamese Americans are an upwardly-mobile group; their economic status improved substantially between 1989 and 1999.[9]

Most first-wave Vietnamese immigrants initially worked at low-paying jobs in small services or industries.[19] Finding work was more difficult for second-wave and subsequent immigrants, due to their limited educational background and job skills. They were employed in blue-collar jobs, such as electrical engineering and machine assembling.[16] In San Jose, California, the economic difference can be seen in the Vietnamese-American neighborhoods of Santa Clara County. In downtown San Jose, many Vietnamese work as restaurant cooks, repairmen and movers. The Evergreen and Berryessa sections of the city are middle- to upper-middle-class neighborhoods with large Vietnamese-American populations, many of whom work in Silicon Valley's computer, networking and aerospace industries.

Many Vietnamese Americans have established businesses in Little Saigons and Chinatowns throughout North America, and have initiated the development and revitalization of older Chinatowns. Many Vietnamese Americans are small business owners. According to a 2002 Census Bureau survey of Vietnamese-owned firms, more than 50 percent of the businesses are personal services or repair and maintenance. The period from 1997 to 2002 saw substantial growth in the number of Vietnamese-owned business.[20] Throughout the country, many Vietnamese (especially first or second-generation immigrants) have opened supermarkets, restaurants, bánh mì bakeries, beauty salons, barber shops and auto-repair businesses. Restaurants owned by Vietnamese Americans tend to serve Vietnamese cuisine, Vietnamized Chinese cuisine or both, and have popularized phở and chả giò in the U.S. In 2002 34.2 percent of Vietnamese-owned businesses were in California, followed by Texas with 16.5 percent.[20]

Young Vietnamese Americans adults are well educated, and often provide professional services. Since older Vietnamese Americans have difficulty interacting with the non-Vietnamese professional class, many Vietnamese Americans provide specialized professional services to fellow immigrants. Of these, a small number are owned by Vietnamese Americans of Hoa ethnicity. In the Gulf Coast region (Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi and Alabama), Vietnamese Americans are involved with the fishing industry and account for 45 to 85 percent of the region's shrimp business. However, the dumping of imported shrimp from Vietnam has impacted their livelihood.[21] Many remain employed in Silicon Valley's computer and networking industry, despite layoffs following the closure of various high-tech companies. Recent immigrants not yet proficient in English work in assembly, restaurants, shops and nail and hair salons. Eighty percent of California's nail technicians and 43 percent nationwide are Vietnamese Americans.[22] Nail-salon work is skilled manual labor which requires limited English-speaking ability. Some Vietnamese Americans see the work as a way to accumulate wealth quickly, and many send remittances to family members in Vietnam. Vietnamese entrepreneurs in Canada and Europe have adopted the U.S. model and opened nail salons in their country of residence, where few nail salons previously existed.

Political activism

According to a 2008 Manhattan Institute study, Vietnamese Americans are among the most-assimilated immigrant groups in the United States.[23] Although their rates of cultural and economic assimilation were comparable to other groups (perhaps due to language differences between English and Vietnamese), their rates of civic assimilation were the highest of the large immigrant groups.[23] As political refugees, Vietnamese Americans viewed their stay in the United States as permanent and became involved in the political process at a higher rate than other groups. Vietnamese Americans have the highest rate of naturalization among all immigrant groups: in 2015, 86% of Vietnamese immigrants in the United States who were eligible for citizenship already became citizens.[24]

"Socialization processes due to unique experiences during a critical imprinting experience among Vietnamese immigrants form an explanation that relies on duration of time spent in the United States. Immigrant cohorts, as instantiated in waves of immigration, are of course related to years spent in the destination country ..."[25] However, there are "substantive within-group differences among Vietnamese Americans and that the classical linear assimilation hypothesis does not adequately explain political incorporation. Although naturalization does appear to increase steadily over time, with earlier waves more likely to have acquired citizenship, the same pattern of associations does not appear for our analysis of registration and voting. Notably, it was the third wave of Vietnamese immigrants who were most likely to cast ballots in the last presidential election".[25]

The relationship between Vietnam and the United States has been the most important issue for most Vietnamese Americans.[16] As refugees from a communist country, many are strongly opposed to communism. In a 2000 Orange County Register poll, 71 percent of respondents ranked fighting communism as a "top priority" or "very important".[26] Vietnamese Americans stage protests against the Vietnamese government, its human rights policy and those whom they perceive to be sympathetic to it.[27] In 1999, opposition to a video-store owner in Westminster, California who displayed the flag of Vietnam and a photo of Ho Chi Minh peaked when 15,000 people held a nighttime vigil in front of the store;[28] this raised free speech issues. Although few Vietnamese Americans enrolled in the Democratic Party because it was seen as more sympathetic to communism than the Republican Party, Republican support has eroded in the second generation and among newer, poorer refugees.[29] However, the Republican Party still has strong support; in Orange County, Vietnamese Americans registered as Republicans outnumber registered Democrats (55 and 22 percent, respectively).[30] According to the 2008 National Asian American Survey, 22 percent identified with the Democratic Party and 29 percent with the Republican Party.[31] Exit polls during the 2004 presidential election indicated that 72 percent of Vietnamese American voters in eight eastern states polled voted for Republican incumbent George W. Bush, compared to the 28 percent voting for Democratic challenger John Kerry.[32] In a poll conducted before the 2008 presidential election, two-thirds of Vietnamese Americans who had decided said that they would vote for Republican candidate John McCain.[31] The party's vocal anti-communism is attractive to older and first-generation Vietnamese Americans who arrived during the Reagan administration. Although most Vietnamese overall are registered Republicans, most young Vietnamese lean toward the Democratic Party. An Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) poll found that Vietnamese Americans aged 18–29 favored Democrat Barack Obama by 60 percentage points during the 2008 presidential election.[33] According to a 2012 Pew Research Center survey, 47 percent of registered Vietnamese-American voters leaned Republican and 32 percent Democratic; among Vietnamese Americans overall (including non-registered voters), 36 percent leaned Democratic and 35 percent Republican.[34]

Vietnamese Americans have exercised political power in Orange County, Silicon Valley and other areas, and have attained public office at the local and statewide levels in California and Texas. Janet Nguyen is a member of the California State Senate; Andrew Do is part of the five-member Orange County Board of Supervisors; Bao Nguyen was mayor of Garden Grove, California, and Vietnamese Americans have also been the mayors of Rosemead and Westminster, California. Several serve (or have served) on the city councils of Westminster,[35] Garden Grove and San Jose, California,[36] and Hubert Vo is a member of the Texas state legislature.[37]

In 2008, Westminster became the first city with a majority Vietnamese-American city council.[38] In 2004, Van Tran was elected to the California state legislature. Viet Dinh was the Assistant Attorney General of the United States from 2001 to 2003 and the chief architect of the Patriot Act. In 2006, 15 Vietnamese Americans were running for elective office in California.[39] In August 2014, Fort Hood Col. Viet Xuan Luong became the first Vietnamese-American general in U.S. history.[40] Four Vietnamese Americans have run for a seat in the United States House of Representatives as their party's endorsed candidate.[41][42][43]

Some Vietnamese Americans have lobbied city and state governments to make the flag of South Vietnam (rather than the flag of Vietnam) the symbol of the Vietnamese in the United States, and objections were raised by the Vietnamese government.[44] The California and Ohio state governments enacted laws adopting the South Vietnamese flag in August 2006. Since June 2002, 13 states, seven counties and 85 cities had adopted resolutions recognizing the South Vietnamese flag as the Vietnamese Heritage and Freedom Flag.[45][46][47]

During the months following Hurricane Katrina, the Vietnamese-American community in New Orleans (among the first to return to the city) rallied against a landfill used to dump debris near their community.[48] After months of legal wrangling, the landfill was closed.[49][50] In 2008, Katrina activist Anh "Joseph" Cao won Louisiana's 2nd congressional district seat in the House of Representatives; Cao was the first Vietnamese American elected to Congress.[51]

Since the onset of Hong Kong protests in June 2019, Vietnamese Americans have been the most active Asian Americans rallying in favor of the pro-democracy Hongkongers, organizing vocal marches in California, where their largest community exists. They clashed with pro-communist Mainland Chinese immigrants.[52][53][54] Trúc Hồ, a famed Vietnamese American singer, wrote a song in July 2019 to praise the Hong Kong protesters. The song went viral among Vietnamese and Hong Kong citizens.[55]

Socioeconomics

Income

According to U.S. Census Bureau, in 2017 the median household income for Vietnamese Americans was $65,643[7] compared to $61,372 for the overall U.S. population.[56]

Economics

In 2017, 10.6 percent of Vietnamese Americans lived under the poverty line,[7] lower than the poverty rate for all Americans at 12.3% percent.[56]

Employment

The U.S. Census Bureau reports in 2016 among working Vietnamese Americans (civilian employed population 16 years and over): 32.9% had management, business, science, and arts occupations; 30.9% had service occupations; 17.0% had sales and office occupations, 4.3% had reported natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations; and 15% had natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations.[7]

Though Vietnamese immigration has continued at a fairly steady pace since the 1980s, the pathway to immigration for Vietnamese today has shifted entirely. As opposed to the earlier history of Vietnamese migration that stemmed predominantly from refugees, an overwhelming majority of Vietnamese are now granted LPR on the basis of family sponsored preferences or by way of immediate relatives to U.S. citizens, at 53% and 44% respectively. This marks a complete about face, in 1982, 99% of Vietnamese that were granted LPR were refugees, while today that group compromises a mere 1% of the Vietnamese population.[7]

Education

In 2017, 31.2% of Vietnamese Americans had attained a bachelor's degree or higher.[7]

English proficiency

In 2017, 51% of Vietnamese in the U.S. reported as being English proficient.[57]

View of education

The Vietnamese parents consider children's educational achievements a source of pride for the family, encouraging their children to excel in school and to enter professional fields as the ticket to a better life. Vietnam's traditional Confucianist society values education and learning, and many Vietnamese Americans have worked their way up from menial labor to have their second-generation children attend college and become successful. Compared to other Asian immigrant groups, Vietnamese Americans are optimistic about their children's future; forty-eight percent believe that their children's standard of living will be better than theirs.[58]

Student associations

A number of colleges have a Vietnamese Student Association, and an annual conference is hosted by the Union of North American Vietnamese Student Associations for current or future members.[59]

Culture

While adapting to a new country, Vietnamese Americans have tried to preserve their traditional culture by teaching their children the Vietnamese language, wearing traditional dress (áo dài) for special occasions and showcasing their cuisine in restaurants throughout the country. Family loyalty is the most important Vietnamese cultural characteristic, and more than two generations traditionally lived under one roof. The Vietnamese view a family as including maternal and paternal grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins. In adapting to American culture, most Vietnamese American families have adopted the nuclear pattern while trying to maintain close ties with their extended families.[16]

Vietnamese family culture is reflected in veneration of the dead. On the anniversary of an ancestor's death (ngày giỗ), relatives gather for a festive meal and to share stories about the person's children, works or community.[15] In a typical Vietnamese family, parents see themselves with a vital role in their children's lives; according to a survey, 71 percent of Vietnamese-American parents said that being a good parent is one of the most important things in their lives.[58] Generations of Vietnamese were taught to help their families without question, and many Vietnamese Americans send American goods and money and sponsor relatives' trips or immigration to the U.S. In 2013, remittances sent to Vietnam via formal channels totaled $11 billion, a tenfold increase from the late 1990s.[9]

Vietnamese Americans observe holidays based on their lunisolar calendar, with Tết Nguyên Đán (commonly known as Tết) the most important. Falling in late January or early February, Tết marks the lunar new year. Although the full holiday lasts for seven days, the first three days are celebrated with visits to relatives, teachers and friends. For Tết, the Vietnamese commemorate their ancestors with memorial feasts (including traditional foods such as square and round sticky-rice cakes: bánh chưng and bánh giầy) and visits to their ancestors' graves.[15][16][17] For Vietnamese Americans, the celebration of Tết is simpler. In California, Texas and other states with substantial Vietnamese communities, Vietnamese Americans celebrate Tết by visiting their relatives and friends, watching community-sponsored dragon dances and visiting temples or churches.[16][17]

Tết Trung Nguyên (Wandering Souls' Day, on the 15th day of the seventh lunar month) and Tết Trung Thu (Children's Day or the Mid-Autumn Festival, on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month) are also celebrated by many Vietnamese Americans. For Tết Trung Nguyên, food, money and clothes made of special paper are prepared to worship the wandering souls of ancestors. Along with Tết Nguyên Đán, Tết Trung Thu is a favorite children's holiday; children holding colorful lanterns form a procession and follow a parade of lion dances and drums.[15][16][17]

Religion

Religious Makeup of Vietnamese-Americans (2012)[60]

Forty-three percent of Vietnamese Americans are Buddhist.[3] Many practice Mahayana Buddhism,[15][16] Taoism, Confucianism and animist practices (including ancestor veneration) influenced by Chinese folk religion.[61] Twenty-nine to forty percent of Vietnamese Americans are Roman Catholic, a legacy of French colonialism and Operation Passage to Freedom. A smaller number are Protestants.[61]

There are 150 to 165 Vietnamese Buddhist temples in the United States, with most observing a mixture of Pure Land (Tịnh Độ Tông) and Zen (Thiền) doctrines and practices.[62][63] Most temples are small, consisting of a converted house with one or two resident monks or nuns.[62] Two of the most prominent figures in Vietnamese-American Buddhism are Thich Thien-An and Thich Nhat Hanh.[63]

Susceptibility

Like with other ethnic-minority groups, Vietnamese Americans have come into conflict with the broader US population. Gulf Coast fishermen complained about unfair competition from their Vietnamese-American counterparts, and the Ku Klux Klan attempted to intimidate Vietnamese-American shrimp fishermen.[64] The Vietnamese Fishermen's Association, with the aid of the Southern Poverty Law Center, won a 1981 antitrust suit against the Klan.[65]

Min Zhou (professor of sociology and Asian American studies at the University of California) and Carl Bankston (assistant professor of sociology at the University of Southwestern Louisiana) researched and insights from many sources, including the U.S. census, survey data, and their own observations and in-depth interviews. Focusing on the Versailles Village enclave in New Orleans, one of many newly established Vietnamese communities in the United States, the authors examine the complex of family, community, and school influences that shape these children's lives.[66] had a "valedictorian / delinquent" susceptibility of Vietnamese-American youth. Vietnamese-American communities have dense, organized social ties, which encourage and socially control children.

The communities were often in economically-disadvantaged neighborhoods, on the margins of American society. Vietnamese children who maintained close connections to their communities are often driven to succeed, but others often fell into delinquency.[67] The 2016 U.S. Census may be an indicator, however, that Vietnamese children are achieving more academic success with 37% of U.S. born Vietnamese having attained a bachelor's degree.[57]

Ethnic subgroups

Although census data counts those who identify as ethnically Vietnamese, how Vietnamese ethnic groups view themselves may affect that reporting.

Hoa

The Hoa people are ethnic Chinese who migrated to Vietnam. In 2013, they made up 11.5 percent of the Vietnamese-American population.[68] Some Hoa Vietnamese Americans also speak a dialect of Yue Chinese, generally code-switching between Cantonese and Vietnamese to speak to both Hoa immigrants from Vietnam and ethnic Vietnamese. Teochew, a variety of Southern Min which had virtually no speakers in the US before the 1980s, is spoken by another group of Hoa immigrants. A small number of Vietnamese Americans may also speak Mandarin as a third (or fourth) language in business and other interaction.

Eurasians and Amerasians

Some Vietnamese Americans are Eurasians: people of European and Asian descent. They are descendants of ethnic Vietnamese and French settlers and soldiers (and sometimes Hoa) during the French colonial period (1883–1945) or the First Indochina War (1946–1954).

Amerasians are descendants of an ethnic Vietnamese (or Hoa) parent and an American parent, most commonly white or black. The first substantial generation of Amerasian Vietnamese Americans were born to American personnel, primarily military men, during the Vietnam War from 1961 to 1975. Many Amerasians were ignored by their American parent; in Vietnam, the fatherless children of foreign men were called con lai ("mixed race") or the pejorative bụi đời ("dust of life").[69] Since 1982, Amerasians and their families have come to the United States under the Orderly Departure Program. Many could not be reunited with their fathers, and commonly arrived with their mothers. In some cases, they were part of false families that were created to escape from Vietnam.[17] Many of the first-generation Amerasians and their mothers experienced significant social and institutional discrimination in Vietnam, where they were denied the right to education; discrimination worsening after the 1973 American withdrawal, and by the U.S. government, which discouraged American military personnel from marrying Vietnamese nationals and frequently refused claims of U.S. citizenship that were lodged by Amerasians born in Vietnam if their mothers were not married to their American fathers.[70][71][72]

Discrimination was even greater for children of black servicemen than for children of white fathers.[73] Subsequent generations of Amerasians (children born in the United States) and Vietnamese-born Amerasians whose American paternity was documented by their parents' marriage or their subsequent legitimization have had an arguably more favorable outlook.[74]

The 1988 American Homecoming Act helped over 25,000 Amerasians and their 67,000 relatives in Vietnam, to emigrate to the United States. Although they received permanent-resident status, many have been unable to obtain citizenship and express a lack of belonging or acceptance in the US because of differences in culture, language and citizenship status.[75][76]

Ethnic Khmer and Cham

Over a million Khmer and a large population of Cham are native to Vietnam, and some of them came to the United States as refugees, however most of them now consider themselves part of much larger Cambodian American community.

See also

Further reading

- Chan, Sucheng, ed. . The Vietnamese American 1.5 Generation: Stories of War, Revolution, Flight, and New Beginnings (2006) 323pp

- Tran, Tuyen Ngoc, "Behind the Smoke and Mirrors: The Vietnamese in California, 1975–1994" (PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 2007). Dissertation Abstracts International, 2008, Vol. 69 Issue 3, p1130-1130,

- Min Zhou and Carl L. Bankston, Growing Up American: How Vietnamese Children Adapt to Life in the United States (1998) New York: Russell Sage Foundation

References

- "ACS Selected Population Profile in the United States (2018 ACS 1-Year Estimates)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "Vietnamese American Populations by Metro Area 2010 Census" (PDF). Hmongstudies.org. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- POLL July 19, 2012 (2012-07-19). "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths". Pew Forum. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- "Pew Forum - Vietnamese Americans' Religions". Projects.pewforum.org. 2012-07-18. Archived from the original on 2013-09-09. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- James M. Freeman. Vietnamese Americans. Microsoft Encarta Online. Encyclopedia 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-04-04. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Southeast Asian Americans State Populations 2010 U.S. Census". Retrieved 2014-01-02.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "2012 American Community Survey: Selected Population Profile in the United States". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12.

- "Vietnamese Immigrants in the United States". Migrationpolicy.org. Migration Information Source. 13 September 2018.

- "ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12.

- Bankston, Carl L. III. 2000. "Vietnamese American Catholicism: Transplanted and Flourishing." U.S. Catholic Historian 18 (1): 36-53

- "Vietnamese-American". EveryCulture.

- "Truong - Ancestry.com". Search.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- "Nguyen - Ancestry.com". Search.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- Wieder, Rosalie. "Vietnamese American". In Reference Library of Asian America, vol I, edited by Susan Gall and Irene Natividad, 165-173. Detroit: Gale Research Inc., 1996

- Bankston, Carl L. "Vietnamese American." In Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America vol 2, edited by Judy Galens, Anna Sheets, and Robyn V. Young, 1393-1407. Detroit: Gale Research Inc., 1995

- Nguyen-Hong-Nhiem, Lucy and Joel M.Halpen. "Vietnamese". In American Immigrant Cultures, vol 2, edited by David Levinson and Melvin Ember, pp. 923-930. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 1998

- Chung, R. C; Bemak, F.; Wong, S. (2000). "Vietnamese refugees' level of distress, social support, and acculturation: Implications for mental health counseling". Journal of Mental Health & Counseling (22): 150–161.

- Anh, Do (May 1, 2015). "On anniversary, Vietnamese Americans reflect on their journeys". Los Angeles Times.

- "Survey of Business Owners - Vietnamese-Owned Firms: 2002". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-05-15.

- Archived May 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- My-Thuan Tran (2008-05-05). "Vietnamese nail down the U.S. manicure business". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- Jacob L. Vigdor (May 2008). "Measuring Immigrant Assimilation in the United States". Manhattan Institute. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- Gonzalez-Barrera, Ana; Krogstad, Jens Manuel (2018-01-18). "Naturalization rate among U.S. immigrants up since 2005, with India among the biggest gainers". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- Le, L. K., & Su, P. H. (2016). Vietnamese Americans and Electoral Participation. In K. L. Kreider & T. J. Baldino (Eds.), Minority Voting in the United States, (pp. 363, 365, 349-368), Santa Barbara: Praeger Press.

- Collet, Christian (May 26, 2000). "The Determinants of Vietnamese American Political Participation: Findings from the January 2000 Orange County Register Poll" (PDF). 2000 Annual Meeting of the Association of Asian American. Scottsdale, Arizona. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008.

- Ong, Nhu-Ngoc T.; Meyer, David S. (April 1, 2004). "Protest and Political Incorporation: Vietnamese American Protests, 1975–2001". Center for the Study of Democracy. 04 (8).

- Nancy Wride; Harrison Sheppard (February 27, 1999). "Little Saigon Vigil Protests Vietnam Human Rights Violations". Los Angeles Times.

- My-Thuan Tran & Christian Berthelsen (2008-02-29). "Leaning left in Little Saigon". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- "OC Blog: Post-Election Spinning". Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

- Jane Junn; Taeku Lee; S. Karthick Ramakrishnan; Janelle Wong (2008-10-06). "National Asian American Survey: Asian Americans and the 2008 Election" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-29. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- Stephanie Ebbert (April 26, 2005). "Asian-Americans step up to ballot box". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- Yzaguirre, Mark. "GOP Losing Vietnamese American Voters". Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "Chapter 6: Political and Civic Life - Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project". 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Mayor Bao Nguyen - City of Garden Grove". 15 December 2014. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- San Jose Councilwoman Madison Nguyen

- Representatives, Texas House of. "Texas House of Representatives". House.state.tx.us. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- My-Thuan Tran (2008-12-02). "Orange County's final vote tally puts 2 Vietnamese Americans in winners' seats". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- "Top 10 web hosting companies 2017 - sites & providers reviews". NCM Online. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Jankowski, Philip. "Fort Hood's Luong to become first Vietnamese-American general". Statesman.com.

- "About this Collection - United States Elections Web Archive". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Archived 2006-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Tan Nguyen for Congress". 4 October 2006. Archived from the original on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Anh, Do (April 25, 2015). "Vietnamese immigrants mark Black April anniversary". Los Angeles Times.

- Resolution Recognizing: The Yellow Flag With Three Red Stripes as The Official Flag of the Vietnamese American Archived October 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "A Map and List of state and city legislation recognizing the Freedom and Heritage Flag". Translate.google.com. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

- "List of states and cities that recognize the Vietnam Freedom and Heritage Flag". Vatv.org. Archived from the original on 2015-10-18. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

- Leslie Eaton (2006-05-06). "A New Landfill in New Orleans Sets Off a Battle". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- Michael Kunzelman (2007-10-31). "After Katrina, Vietnamese become political force in New Orleans". Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- S. Leo Chiang (2008-08-28). "New Orleans: A Village Called Versailles: After tragedy, a community finds its political voice". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- "Indicted Louisiana Rep. William J. Jefferson loses reelection bid". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 2008-12-07. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- "Pro-Hong Kong demonstrations in U.S. met with China-supporting counterprotesters". NBC News. 2019-09-05. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- "Hong Kong protests: Vietnamese immigrants rally in L.A." Los Angeles Times. 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- "Vietnamese stand in solidarity with ongoing Hong Kong protests". AsAm News. 2019-12-16. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- "Video: Vietnamese-American musician's song in support of anti-extradition protesters inspires Hongkongers". Hong Kong Free Press. 2019-07-24. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- Bureau, US Census. "Income and Poverty in the United States: 2017". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- "Vietnamese American". PewResearch Social & Demographic Trends. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- Bronner, Simon J.; Clark, Cindy Dell (21 March 2016). Youth Cultures in America. ABC-CLIO, 2016. p. 647. ISBN 978-1440833922.

- "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths". Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Lee, Jonathan H. X.; Kathleen M. Nadeau (2011). Encyclopedia of Asian American folklore and folklife. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1204–1206. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5.

- Laderman, Gary; Luis D. León (2003). Religion and American cultures. ABC-CLIO. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-57607-238-7.

- Prebish, Charles S. (1 December 2003). Buddhism—the American Experience. JBE Online Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-9747055-0-7.

- Archived January 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Chin, Andrew. "The KKK and Vietnamese Fishermen". University of North Carolina School of Law. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- "Russell Sage Foundation". Russellsage.org. Archived from the original on 2009-08-16. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- Smith-Hefner, Nancy Joan (February 1999). "Project MUSE - Journal of Asian American Studies - Growing Up American: How Vietnamese Children Adapt to Life in the United States". Journal of Asian American Studies. 2 (1): 111–113. doi:10.1353/jaas.1999.0005. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- Trieu, M.M. (2013). Chinese-Vietnamese Americans. X. Zhao, & E.J. Park (Eds.), Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History (pp. 305-310). Santa Barbara, USA: Greenwood.

- "Vietnamerica: The War Comes Home". Archived from the original on March 24, 2006. Retrieved November 18, 2006.

- "Amerasian Citizenship Initiative - Issue Background". AmerasianUSA. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- ""U.S. Legislation Regarding Amerasians". Amerasian Foundation; website retrieved January 3, 2007". Amerasianfoundation.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ""Lofgren Introduces Citizenship Bill for Children Born in Vietnam to American Servicemen and Vietnamese Women During the Vietnam War". Whitehouse.gov; October 22, 2003". House.gov. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- "Yoon, Diana H. "The American Response to Amerasian Identity and Rights". Berkeley McNair Research Journal; Winter, 1999 (vol. 7); pp. 71—84" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ""Vietnamese-Amerasians: Where Do They Belong?" Thanh Tran; December 16, 1999". Mtholyoke.edu. Archived from the original on July 4, 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- Archived March 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Asian Art ← Finest Asian Art". Amerasianusa.org. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vietnamese diaspora in the United States. |

- Teaching Tolerance - Vietnamese Americans

- Census Data

- Vietnamese American population by city

- Vietnamese-American Protests from 1975–2001 by Nhu-Ngoc T. Ong and David S. Meyer

- Vietnamese American Heritage Project at the Smithsonian Institution

- Asian-Nation: Vietnamese American Community by C.N. Le, Ph.D.

- UCI Libraries Southeast Asian Archive

- UCIspace @ the Libraries digital collection: Vietnamese American Oral History Project

- Vietnamese Studies Internet Resource Center

- Documentary film centered on Vietnamese American community in New Orleans

- 30 years after the fall of Saigon: from The Orange County Register

- Vietnamese American history

- Vietnamese who found new lives: from the BBC

- Vietnamese American Council

- National Congress of Vietnamese Americans

- US Census 2000 foreign born population by country

- Vietnamese Families, Family Life, and Gender Roles

- The Three d's of Vietnamese Professionals, by Nguyen Xuan Vinh, May, 1990

- The Experience of Vietnamese Refugee Children in the United States

- Delinquency and Acculturation in a Vietnamese Community

- The Dragon and the Eagle: Toward a Vietnamese American Theology, Originally published in Theology Digest 43:3 (Fall 2001).

- Straddling Different Worlds: The Acculturation of Vietnamese Refugee Children by Min Zhou

- Vietnamese-American Catholicism: Transplanted and Flourishing by Carl L. Bankston III

- "Vietnamese Buddhism In America" by Thầy Thích Minh Quang, PhD