Norwegian Vietnamese

Norwegian Vietnamese or Vietnamese Norwegian refers to citizens or naturalized residents of Norway of Vietnamese descent.

| |||

| Total population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 23,313 (2019 Official Norway estimate)[1] 0.44% of the Norwegian population | |||

| Regions with significant populations | |||

| Oslo, Bergen, Kristiansand, Trondheim, Stavanger, Moss, Drammen | |||

| Languages | |||

| Vietnamese, Norwegian | |||

| Religion | |||

| Predominantly Mahayana Buddhism with Ancestor Worship,[2] and Roman Catholicism | |||

| Related ethnic groups | |||

| Vietnamese people, Overseas Vietnamese | |||

When this article describes Vietnamese living in Norway, it primarily means persons with two parents born in Vietnam. Thus, statistics used in this article do not include Vietnamese-descended persons with only one parent, or no parents born in Vietnam.

History

The first waves of Vietnamese immigrants to Norway came after the Fall of Saigon, in 1975. They escaped Vietnam by boat, and were also known as the boat people. Some were picked up by Norwegian cargo ships and came to Norway after spending some months in refugee camps in East Asia and Southeast Asia. Most of these boat people came in the period from 1978 to 1985. Later immigrants have come as a cause of family-reunification and economic reasons.

Demographics

On January 1, 2017, the Norwegian Statistisk Sentralbyrå reported that there were 22,658 Vietnamese people in Norway. Vietnamese Norwegians were the fourth-largest immigrant group from outside Europe after Pakistanis, Somalis and Iraqis.

The Vietnamese were among the first from the third world to immigrate to Norway. Eight out of ten Vietnamese have lived in Norway for more than ten years, and nine out of ten possess Norwegian citizenship.[3]

Settlement

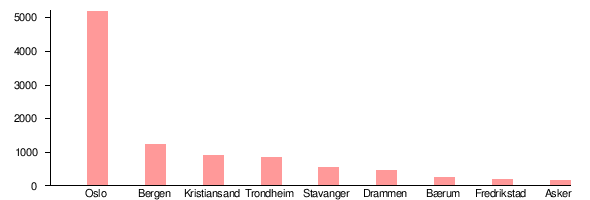

Around 6,000 Vietnamese Norwegians live in Oslo (around 27% of the Vietnamese population in Norway) , where they are the eleventh-largest immigrant group. There are also significant groups of Vietnamese living in the citys of Bergen, Kristiansand, and Trondheim.

|

| Number of immigrant with Vietnamese background in some municipalities 1 January 2008[4] |

Cultural profile

Education

Vietnamese culture places heavy emphasis on education. Even though the elder first generation immigrants in the age of 30 to 44 often do not have a higher education, the second generation, and the younger first generation immigrants from 19 to 24 years old, generally have a much higher education level. A 2012 study found that Vietnamese Norwegians—both those born in Norway, and the foreign-borns—had slightly better grades than ethnic Norwegians in secondary school despite their parents having lower education.[5][6] A survey from 2006 reported that 88 percent of Vietnamese finished upper secondary school, the same percent as ethnic Norwegians.[7] A 2006 survey also showed that Vietnamese had the highest grades in upper secondary school among the ten largest non-western immigrant groups in Norway, averaging similar grades as Norwegians.[8][9]

A 2006 survey showed that Vietnamese was the ethnic group that had the fourth highest percentage whom finished a bachelor degree (after Indians, Chinese, and Norwegians) and the ethnic group with the third highest percentage whom finished a masters degree.[10] The Vietnamese especially have many representatives in higher education, as there is a 10 percent bigger chance for a Vietnamese-Norwegian having finished higher education than a Norwegian.[11]

Politics

Vietnamese in Norway are not active in the country's politics. As of December 2006, there was only one Vietnamese in a municipal council in Norway.[12] At the municipal- and countyelection (kommune- og fylkestingsvalg) in 2003, only 30 percent of the Vietnamese-Norwegians voted.[13] It has been pointed out that though the voting percentage of elder Vietnamese (40 to 59 years old) at 51% is relatively high—compared to other non-western immigrant groups of the same age (44%)—it is the younger generation of Vietnamese Norwegians that pull the numbers down. In 2003, only 17% of the Vietnamese Norwegians in the age groups between 18 and 25, and 22% between 26 and 39, voted.[14]

Attachments to home country

As a result of most Vietnamese coming to Norway as political or war refugees fleeing the Communist Vietnam, they are in general critical of the Vietnamese government. Fleeing the country was viewed as treason by the Vietnamese government during the 1970s and 1980s. However, the trend has turned and Vietnam now view the overseas Vietnamese as assets to the country's rapidly growing economy.

The Vietnamese are one of the immigrant groups in Norway that most often send money to families in their home country. Over 60% of those who came to the country as adults reported as regularly sending money home to their families. The number regularly sending money to Vietnam among Vietnamese-born in Norway or arrived in the country as children, were over 40%. The Vietnamese coming to Norway as adults send more and more money, the longer they have stayed in their new country.[15]

Issues

Though widely perceived as one of the best integrated non-western immigrant groups, there still remain some challenges for the Vietnamese community in Norway. A 2002 survey reported that 3.2% of Vietnamese Norwegians had been punished for breaking the law. The number for ethnic Norwegians were 1.35%.[16] A social anthropologist studying the Vietnamese community said there was an "either...or" phenomenon among the Vietnamese, with those not succeeding in school falling into delinquency.[16] The same trend has also been observed among the Vietnamese Americans. A stronger connection between the parents and the kids that fall out has been wanted. The relative low proficiency among Vietnamese in Norwegian, and a small vocabulary, has also been analysed as important challenges remaining.

Psychological problems

Many Vietnamese, especially among the older generation, have experienced traumas during and after the Vietnam War. A survey conducted on 148 randomly chosen Vietnamese refugees, up to three years after arriving in Norway, showed that many of them had experienced war up close.[17] Sixty-two percent had witnessed bombings, fires, and shooting, and forty-eight percent had witnessed someone been injured or killed. One out of four had been in life-threatening situations and/or injured during the war. One out of ten had been in re-education camps. Former inmates describe them as close to concentration camps, where they did not know how long they had to stay, and were victims of extreme methods of punishing.

The traumas affected the refugees psychological health even seven years after the war. After three years in Norway, there was still no sign of change in the psychological strain on the refugees. One out of four had a psychological suffering. Depression was the most common diagnosis, with 18% being clinically depressed. Psychological illness in Norway was linked with traumas experienced during the time in Vietnam, in addition to lack of an entrusted partner during the escape from the country, and severance from close family. One out of three reported post-traumatic worries, and one out of ten were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Notable people

References

- "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents, 1 January 2014". Statistics Norway. Accessed 29 April 2014.

- "Vietnamese Buddhist centers in Norway", World Buddhist Directory, 2013, retrieved 2013-07-22

- "Fakta om 18 innvandrergrupper i Norge" (PDF). Statistisk Sentralbyrå. 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- "Innvandrerbefolkningen, etter landbakgrunn (de 20 største gruppene). Utvalgte kommuner. 1. januar 2008". Statistisk Sentralbyrå. 2008. Archived from the original on 2012-05-26. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- Alice Steinkellner. "Innvandrere og norskfødte med innvandrerforeldre i grunnskolen" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- Per Anders Johansen, Andreas Slettholm (December 28, 2013). "Mor og far er innvandrere. Men barna fikser likevel skolen bedre". Aftenposten. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- Anbjørg Bakken (June 20, 2006). "Flittigere enn gutta". Aftenposten. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- Liv Anne Støren. "Nasjonalitetsforskjeller i karakterer i videregående opplæring" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- Ann Christiansen (November 2, 2006). "Gjør det best blant innvandrere". Aftenposten. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- Dag Yngve Dahle (March 2, 2006). "Best utdannet i øst". Aftenposten. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- Silje Noack Fekjær (2006). "Utdanning hos annengenerasjon etniske minoriteter i Norge" (PDF). Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- Wasim K. Riaz (November 14, 2006). "17 000 vietnamesere, én politiker". Aftenposten. Archived from the original on July 13, 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- "Lav valgdeltakelse blant innvandrerne". Statistisk sentralbyrå. March 2004. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- Khang Ngoc Nguyen (August 28, 2007). "Myter og fakta om valgdeltakelse blant vietneamsere i Norge". Statistisk sentralbyrå. Archived from the original on January 31, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- Jørgen Carling (December 9, 2004). "Innvandrere prioriterer å sende penger til familien". Statistisk sentralbyrå. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- Astrid Meland (April 28, 2005). "Mer kriminelle enn nordmenn". Dagbladet. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- Evard Hauff (1999). "Vietnamesiske flyktninger i Norge - noen refleksjoner i etterkant av et forskningsprosjekt" (PDF). Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter om vold og traumatisk stress. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

See also

- Norwegian people

- Vietnamese people

.jpg)