Elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the flowering plant genus Ulmus in the plant family Ulmaceae. The genus first appeared in the Miocene geological period about 20 million years ago, originating in what is now central Asia.[1] These trees flourished and spread over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical-montane regions of North America and Eurasia, presently ranging southward in the Middle East to Lebanon, and Israel [2], and across the Equator in the Far East into Indonesia.[3]

| Elm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ulmus minor,

East Coker, Somerset, UK. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Ulmaceae |

| Genus: | Ulmus L. |

| Species | |

|

See

| |

Elms are components of many kinds of natural forests. Moreover, during the 19th and early 20th centuries many species and cultivars were also planted as ornamental street, garden, and park trees in Europe, North America, and parts of the Southern Hemisphere, notably Australasia. Some individual elms reached great size and age. However, in recent decades, most mature elms of European or North American origin have died from Dutch elm disease, caused by a microfungus dispersed by bark beetles. In response, disease-resistant cultivars have been developed, capable of restoring the elm to forestry and landscaping.

Taxonomy

There are about 30 to 40 species of Ulmus (elm); the ambiguity in number results from difficulty in delineating species, owing to the ease of hybridization between them and the development of local seed-sterile vegetatively propagated microspecies in some areas, mainly in the field elm (Ulmus minor) group. Oliver Rackham[4] describes Ulmus as the most critical genus in the entire British flora, adding that 'species and varieties are a distinction in the human mind rather than a measured degree of genetic variation'. Eight species are endemic to North America, and a smaller number to Europe;[5] the greatest diversity is found in Asia.[3]

The classification adopted in the List of elm species, varieties, cultivars and hybrids is largely based on that established by Brummitt.[6] A large number of synonyms have accumulated over the last three centuries; their currently accepted names can be found in the list List of elm Synonyms and Accepted Names.

Botanists who study elms and argue over elm identification and classification are called pteleologists, from the Greek πτελέα (:elm).[7]

As part of the sub-order urticalean rosids they are distant cousins of cannabis, hops, and nettles.

Etymology

The name Ulmus is the Latin name for these trees, while the English "elm" and many other European names are either cognate with or derived from it.[8]

Description

The genus is hermaphroditic, having apetalous perfect flowers which are wind-pollinated. Elm leaves are alternate, with simple, single- or, most commonly, doubly serrate margins, usually asymmetric at the base and acuminate at the apex. The fruit is a round wind-dispersed samara flushed with chlorophyll, facilitating photosynthesis before the leaves emerge.[9] The samarae are very light, those of British elms numbering around 50,000 to the pound (454 g).[10] All species are tolerant of a wide range of soils and pH levels but, with few exceptions, demand good drainage. The elm tree can grow to great height, often with a forked trunk creating a vase profile.

'Sapporo Autumn Gold', Antella, Florence

'Sapporo Autumn Gold', Antella, Florence Wych elm (Ulmus glabra) leaves and seeds

Wych elm (Ulmus glabra) leaves and seeds Asymmetry of leaf, Slippery Elm U. rubra

Asymmetry of leaf, Slippery Elm U. rubra Mature bark, Slippery Elm U. rubra

Mature bark, Slippery Elm U. rubra Flowers of the hybrid elm cultivar 'Columella'

Flowers of the hybrid elm cultivar 'Columella' Corky wings, Winged Elm U. alata

Corky wings, Winged Elm U. alata U. laciniata samara

U. laciniata samara U. americana, Dufferin St., Toronto, c. 1914

U. americana, Dufferin St., Toronto, c. 1914

Pests and diseases

Dutch elm disease

Dutch elm disease (DED) devastated elms throughout Europe and much of North America in the second half of the 20th century. It derives its name 'Dutch' from the first description of the disease and its cause in the 1920s by the Dutch botanists Bea Schwarz and Christina Johanna Buisman. Owing to its geographical isolation and effective quarantine enforcement, Australia, has so far remained unaffected by Dutch Elm Disease, as have the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia in western Canada.

DED is caused by a micro-fungus transmitted by two species of Scolytus elm-bark beetle which act as vectors. The disease affects all species of elm native to North America and Europe, but many Asiatic species have evolved anti-fungal genes and are resistant. Fungal spores, introduced into wounds in the tree caused by the beetles, invade the xylem or vascular system. The tree responds by producing tyloses, effectively blocking the flow from roots to leaves. Woodland trees in North America are not quite as susceptible to the disease because they usually lack the root-grafting of the urban elms and are somewhat more isolated from each other. In France, inoculation with the fungus of over three hundred clones of the European species failed to find a single variety possessed of any significant resistance.

The first, less aggressive strain of the disease fungus, Ophiostoma ulmi, arrived in Europe from Asia in 1910, and was accidentally introduced to North America in 1928. It was steadily weakened by viruses in Europe and had all but disappeared by the 1940s. However, the disease had a much greater and long-lasting impact in North America, owing to the greater susceptibility of the American elm, Ulmus americana, which masked the emergence of the second, far more virulent strain of the disease Ophiostoma novo-ulmi. It appeared in the United States sometime in the 1940s, and was originally believed to be a mutation of O. ulmi. Limited gene flow from O. ulmi to O. novo-ulmi was probably responsible for the creation of the North American subspecies O. novo-ulmi subsp. americana. It was first recognized in Britain in the early 1970s, believed to have been introduced via a cargo of Canadian rock elm destined for the boatbuilding industry, and rapidly eradicated most of the mature elms from western Europe. A second subspecies, O. novo-ulmi subsp. novo-ulmi, caused similar devastation in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. It is now believed that it was this subspecies which was introduced to North America and, like O. ulmi, probably originated in Asia. The two subspecies have now hybridized in Europe where their ranges have overlapped.[11] The hypothesis that O. novo-ulmi arose from a hybrid of the original O. ulmi and another strain endemic to the Himalaya, Ophiostoma himal-ulmi is now discredited.[12]

There is no sign of the current pandemic waning, and no evidence of a susceptibility of the fungus to a disease of its own caused by d-factors: naturally occurring virus-like agents that severely debilitated the original O. ulmi and reduced its sporulation.[13]

Elm phloem necrosis

Elm phloem necrosis (elm yellows) is a disease of elm trees that is spread by leafhoppers or by root grafts.[14] This very aggressive disease, with no known cure, occurs in the Eastern United States, southern Ontario in Canada, and Europe. It is caused by phytoplasmas which infect the phloem (inner bark) of the tree.[15] Infection and death of the phloem effectively girdles the tree and stops the flow of water and nutrients. The disease affects both wild-growing and cultivated trees. Occasionally, cutting the infected tree before the disease completely establishes itself and cleanup and prompt disposal of infected matter has resulted in the plant's survival via stump-sprouts.

Insects

Most serious of the elm pests is the elm leaf beetle Xanthogaleruca luteola, which can decimate foliage, although rarely with fatal results. The beetle was accidentally introduced to North America from Europe. Another unwelcome immigrant to North America is the Japanese beetle Popillia japonica. In both instances the beetles cause far more damage in North America owing to the absence of the predators present in their native lands. In Australia, introduced elm trees are sometimes used as foodplants by the larvae of hepialid moths of the genus Aenetus. These burrow horizontally into the trunk then vertically down.[16][17]

Birds

Sapsucker woodpeckers have a great love of young elm trees.

Development of trees resistant to Dutch elm disease

Efforts to develop DED-resistant cultivars began in the Netherlands in 1928 and continued, uninterrupted by World War II, until 1992.[18] Similar programmes were initiated in North America (1937), Italy (1978), and Spain (1986). Research has followed two paths:

Species and species cultivars

In North America, careful selection has produced a number of trees resistant not only to DED, but also to the droughts and cold winters that occur within the continent. Research in the United States has concentrated on the American elm (Ulmus americana), resulting in the release of DED-resistant clones, notably the cultivars 'Valley Forge' and 'Jefferson'. Much work has also been done into the selection of disease-resistant Asiatic species and cultivars.[19][20]

In 1993, Mariam B. Sticklen and James L. Sherald reported the results of experiments funded by the United States National Park Service and conducted at Michigan State University in East Lansing that were designed to apply genetic engineering techniques to the development of DED-resistant strains of American elm trees.[21] In 2007, AE Newhouse and F Schrodt of the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse reported that young transgenic American elm trees had shown reduced DED symptoms and normal mycorrhizal colonization.[22]

In Europe, the European white elm (Ulmus laevis) has received much attention. While this elm has little innate resistance to Dutch elm disease, it is not favoured by the vector bark beetles and thus only becomes colonized and infected when there are no other choices, a rare situation in western Europe. Research in Spain has suggested that it may be the presence of a triterpene, alnulin, which makes the tree bark unattractive to the beetle species that spread the disease.[23] However this possibility has not been conclusively proven.[24] More recently, field elms Ulmus minor highly resistant to DED have been discovered in Spain, and form the basis of a major breeding programme.[25]

Hybrid cultivars

Owing to their innate resistance to Dutch elm disease, Asiatic species have been crossed with European species, or with other Asiatic elms, to produce trees which are both highly resistant to disease and tolerant of native climates. After a number of false dawns in the 1970s, this approach has produced a range of reliable hybrid cultivars now commercially available in North America and Europe.[26][27][28][29][30][31][32] Disease resistance is invariably carried by the female parent.[33]

However, some of these cultivars, notably those with the Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila) in their ancestry, lack the forms for which the iconic American Elm and English Elm were prized. Moreover, several exported to northwestern Europe have proven unsuited to the maritime climate conditions there, notably because of their intolerance of anoxic conditions resulting from ponding on poorly drained soils in winter. Dutch hybridizations invariably included the Himalayan elm (Ulmus wallichiana) as a source of anti-fungal genes and have proven more tolerant of wet ground; they should also ultimately reach a greater size. However, the susceptibility of the cultivar 'Lobel', used as a control in Italian trials, to elm yellows has now (2014) raised a question mark over all the Dutch clones.[34]

A number of highly resistant Ulmus cultivars has been released since 2000 by the Institute of Plant Protection in Florence, most commonly featuring crosses of the Dutch cultivar 'Plantijn' with the Siberian Elm to produce resistant trees better adapted to the Mediterranean climate.[27]

Cautions regarding novel cultivars

Elms take many decades to grow to maturity, and as the introduction of these disease-resistant cultivars is relatively recent, their long-term performance and ultimate size and form cannot be predicted with certainty. The National Elm Trial in North America, begun in 2005, is a nationwide trial to assess strengths and weaknesses of the 19 leading cultivars raised in the US over a ten-year period; European cultivars have been excluded. Meanwhile, in Europe, American and European cultivars are being assessed in field trials started in 2000 by the UK charity Butterfly Conservation.[35]

Uses in landscaping

One of the earliest of ornamental elms was the ball-headed graft narvan elm, Ulmus minor 'Umbraculifera', cultivated from time immemorial in Persia as a shade tree and widely planted in cities through much of south-west and central Asia. From the 18th century to the early 20th century, elms, whether species, hybrids or cultivars, were among the most widely planted ornamental trees in both Europe and North America. They were particularly popular as a street tree in avenue plantings in towns and cities, creating high-tunnelled effects. Their quick growth and variety of foliage and forms,[36] their tolerance of air-pollution and the comparatively rapid decomposition of their leaf-litter in the fall were further advantages.

In North America, the species most commonly planted was the American elm (Ulmus americana), which had unique properties that made it ideal for such use: rapid growth, adaptation to a broad range of climates and soils, strong wood, resistance to wind damage, and vase-like growth habit requiring minimal pruning. In Europe, the wych elm (Ulmus glabra) and the field elm (Ulmus minor) were the most widely planted in the countryside, the former in northern areas including Scandinavia and northern Britain, the latter further south. The hybrid between these two, Dutch elm (U. × hollandica), occurs naturally and was also commonly planted. In much of England, it was the English elm which later came to dominate the horticultural landscape. Most commonly planted in hedgerows, it sometimes occurred in densities of over 1000 per square kilometre. In south-eastern Australia and New Zealand, large numbers of English and Dutch elms, as well as other species and cultivars, were planted as ornamentals following their introduction in the 19th century, while in northern Japan Japanese Elm (Ulmus davidiana var. japonica) was widely planted as a street tree. From about 1850 to 1920, the most prized small ornamental elm in parks and gardens was the Camperdown elm (Ulmus glabra 'Camperdownii'), a contorted weeping cultivar of the Wych Elm grafted on to a non-weeping elm trunk to give a wide, spreading and weeping fountain shape in large garden spaces.

In northern Europe elms were, moreover, among the few trees tolerant of saline deposits from sea spray, which can cause "salt-burning" and die-back. This tolerance made elms reliable both as shelterbelt trees exposed to sea wind, in particular along the coastlines of southern and western Britain[37][38] and in the Low Countries, and as trees for coastal towns and cities.[39]

This belle époque lasted until the First World War, when as a consequence of hostilities, notably in Germany whence at least 40 cultivars originated, and of the outbreak at about the same time of the early strain of Dutch elm disease, Ophiostoma ulmi, the elm began its slide into horticultural decline. The devastation caused by the Second World War, and the demise in 1944 of the huge Späth nursery in Berlin, only accelerated the process. The outbreak of the new, three times more virulent, strain of Dutch elm disease Ophiostoma novo-ulmi in the late 1960s brought the tree to its nadir.

Since circa 1990 the elm has enjoyed a renaissance through the successful development in North America and Europe of cultivars highly resistant to DED.[9] Consequently, the total number of named cultivars, ancient and modern, now exceeds 300, although many of the older clones, possibly over 120, have been lost to cultivation. Some of the latter, however, were by today's standards inadequately described or illustrated before the pandemic, and it is possible that a number survive, or have regenerated, unrecognised. Enthusiasm for the newer clones often remains low owing to the poor performance of earlier, supposedly disease-resistant Dutch trees released in the 1960s and 1970s. In the Netherlands, sales of elm cultivars slumped from over 56,000 in 1989 to just 6,800 in 2004,[40] whilst in the UK, only four of the new American and European releases were commercially available in 2008.

Landscaped parks

Central Park

New York City's Central Park is home to approximately 1,200 American elm trees, which constitute over half of all trees in the park. The oldest of these elms were planted during the 1860s by Frederick Law Olmsted, making them among the oldest stands of American elms in the world. The trees are particularly noteworthy along the Mall and Literary Walk, where four lines of American elms stretch over the walkway forming a cathedral-like covering. A part of New York City's urban ecology, the elms improve air and water quality, reduce erosion and flooding, and decrease air temperatures during warm days.[41]

While the stand is still vulnerable to DED, in the 1980s the Central Park Conservancy undertook aggressive countermeasures such as heavy pruning and removal of extensively diseased trees. These efforts have largely been successful in saving the majority of the trees, although several are still lost each year. Younger American elms that have been planted in Central Park since the outbreak are of the DED-resistant 'Princeton' and 'Valley Forge' cultivars.[42]

National Mall

Several rows of American elm trees that the National Park Service (NPS) first planted during the 1930s line much of the 1.9 miles (3.0 km) length of the National Mall in Washington, D.C. DED first appeared on the trees during the 1950s and reached a peak in the 1970s. The NPS used a number of methods to control the epidemic, including sanitation, pruning, injecting trees with fungicide and replanting with DED-resistant cultivars. The NPS combated the disease's local insect vector, the smaller European elm bark beetle (Scolytus multistriatus), by trapping and by spraying with insecticides. As a result, the population of American elms planted on the Mall and its surrounding areas has remained intact for more than 80 years.[43]

Other uses

Wood

.jpg)

Elm wood is valued for its interlocking grain, and consequent resistance to splitting, with significant uses in wagon wheel hubs, chair seats and coffins. The bodies of Japanese Taiko drums are often cut from the wood of old elm trees, as the wood's resistance to splitting is highly desired for nailing the skins to them, and a set of three or more is often cut from the same tree. The elm's wood bends well and distorts easily making it quite pliant. The often long, straight, trunks were favoured as a source of timber for keels in ship construction. Elm is also prized by bowyers; of the ancient bows found in Europe, a large portion are elm. During the Middle Ages elm was also used to make longbows if yew was unavailable.

The first written references to elm occur in the Linear B lists of military equipment at Knossos in the Mycenaean Period. Several of the chariots are of elm (" πτε-ρε-ϝα ", pte-re-wa), and the lists twice mention wheels of elmwood.[44] Hesiod says that ploughs in Ancient Greece were also made partly of elm.[45]

The density of elm wood varies between species, but averages around 560 kg per cubic metre.[46]

Elm wood is also resistant to decay when permanently wet, and hollowed trunks were widely used as water pipes during the medieval period in Europe. Elm was also used as piers in the construction of the original London Bridge. However this resistance to decay in water does not extend to ground contact.[46]

Viticulture

The Romans, and more recently the Italians, used to plant elms in vineyards as supports for vines. Lopped at three metres, the elms' quick growth, twiggy lateral branches, light shade and root-suckering made them ideal trees for this purpose. The lopped branches were used for fodder and firewood.[47] Ovid in his Amores characterizes the elm as "loving the vine": ulmus amat vitem, vitis non deserit ulmum (:the elm loves the vine, the vine does not desert the elm),[48] and the ancients spoke of the "marriage" between elm and vine.[49]

Medicinal products

The mucilaginous inner bark of the Slippery Elm Ulmus rubra has long been used as a demulcent, and is still produced commercially for this purpose in the United States with approval for sale as a nutritional supplement by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.[50]

Fodder

Elms also have a long history of cultivation for fodder, with the leafy branches cut to feed livestock. The practice continues today in the Himalaya, where it contributes to serious deforestation.[51]

Biomass

As fossil fuel resources diminish, increasing attention is being paid to trees as sources of energy. In Italy, the Istituto per la Protezione delle Piante is (2012) in the process of releasing to commerce very fast-growing elm cultivars, able to increase in height by more than 2 m (6 ft) per annum.[52]

Food

Elm bark, cut into strips and boiled, sustained much of the rural population of Norway during the great famine of 1812. The seeds are particularly nutritious, containing 45% crude protein, and less than 7% fibre by dry mass.[53]

Alternative medicine

Elm has been listed as one of the 38 substances that are used to prepare Bach flower remedies,[54] a kind of alternative medicine.

Bonsai

Chinese elm Ulmus parvifolia is a popular choice for bonsai owing to its tolerance of severe pruning.

Genetic resource conservation

In 1997, a European Union elm project was initiated, its aim to coordinate the conservation of all the elm genetic resources of the member states and, among other things, to assess their resistance to Dutch elm disease. Accordingly, over 300 clones were selected and propagated for testing.[55][56][57]

Notable elm trees

Many elm (Ulmus) trees of various kinds have attained great size or otherwise become particularly noteworthy.

In art

Many artists have admired elms for the ease and grace of their branching and foliage, and have painted them with sensitivity. Elms are a recurring element in the landscapes and studies of, for example, John Constable, Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, Frederick Childe Hassam, Karel Klinkenberg,[58] and George Inness.

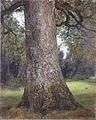

John Constable, 'Study of an Elm Tree' [1821]

John Constable, 'Study of an Elm Tree' [1821] John Constable, 'The Cornfield' [1826] (Ulmus × hollandica[1])

John Constable, 'The Cornfield' [1826] (Ulmus × hollandica[1]) Constable, 'Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Garden' [1823 version] (Ulmus × hollandica[1])

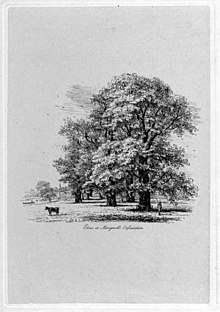

Constable, 'Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Garden' [1823 version] (Ulmus × hollandica[1]) Jacob George Strutt, Elms at Mongewell, Oxfordshire [1830] (Ulmus minor 'Atinia')

Jacob George Strutt, Elms at Mongewell, Oxfordshire [1830] (Ulmus minor 'Atinia') Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, 'Alte Ulmen im Prater' (:Old Elms in Prater) [1831]

Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, 'Alte Ulmen im Prater' (:Old Elms in Prater) [1831] James Duffield Harding, 'The Great Exhibition of 1851' (Ulmus minor 'Atinia', centre)

James Duffield Harding, 'The Great Exhibition of 1851' (Ulmus minor 'Atinia', centre) Arthur Hughes, 'Home from Sea' [1862] (Ulmus minor 'Atinia'[1])

Arthur Hughes, 'Home from Sea' [1862] (Ulmus minor 'Atinia'[1]) Ford Madox Brown, 'Work' [1863] (Ulmus minor 'Atinia'[1])

Ford Madox Brown, 'Work' [1863] (Ulmus minor 'Atinia'[1]).jpg) [unknown artist] The American Elm [1879] (Ulmus americana)

[unknown artist] The American Elm [1879] (Ulmus americana) Johannes Karel Christiaan Klinkenberg, 'Amsterdam' [1890] (Ulmus x hollandica ‘Belgica' )

Johannes Karel Christiaan Klinkenberg, 'Amsterdam' [1890] (Ulmus x hollandica ‘Belgica' )- Frederick Childe Hassam, 'Champs Elysées, Paris' [1889] (Ulmus × hollandica, 'orme femelle'[1])

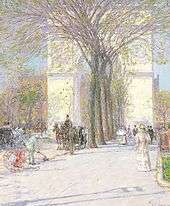

Frederick Childe Hassam, 'Washington Arch, Spring' [1893] (Ulmus americana)

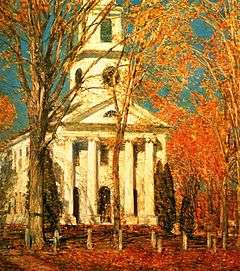

Frederick Childe Hassam, 'Washington Arch, Spring' [1893] (Ulmus americana) Frederick Childe Hassam, 'Church at Old Lyme' [1905] (Ulmus americana)

Frederick Childe Hassam, 'Church at Old Lyme' [1905] (Ulmus americana) Frederick Childe Hassam, 'The East Hampton Elms in May' [1920] (Ulmus americana)

Frederick Childe Hassam, 'The East Hampton Elms in May' [1920] (Ulmus americana) George Inness, 'Old Elm at Medfield' (Ulmus americana)

George Inness, 'Old Elm at Medfield' (Ulmus americana) Unknown artist, 'The Cam near Trinity College, Cambridge', England (Ulmus atinia)

Unknown artist, 'The Cam near Trinity College, Cambridge', England (Ulmus atinia) Sava Šumanović, Elm [1939]

Sava Šumanović, Elm [1939]

In mythology and literature

.png)

In Greek mythology the nymph Ptelea (Πτελέα, Elm) was one of the eight Hamadryads, nymphs of the forest and daughters of Oxylos and Hamadryas.[59] In his Hymn to Artemis the poet Callimachus (3rd century BC) tells how, at the age of three, the infant goddess Artemis practised her newly acquired silver bow and arrows, made for her by Hephaestus and the Cyclopes, by shooting first at an elm, then at an oak, before turning her aim on a wild animal:

- πρῶτον ἐπὶ πτελέην, τὸ δὲ δεύτερον ἧκας ἐπὶ δρῦν, τὸ τρίτον αὖτ᾽ ἐπὶ θῆρα.[60]

The first reference in literature to elms occurs in the Iliad. When Eetion, father of Andromache, is killed by Achilles during the Trojan War, the Mountain Nymphs plant elms on his tomb ("περὶ δὲ πτελέoι εφύτεψαν νύμφαι ὀρεστιάδες, κoῦραι Διὸς αἰγιόχoιo").[61] Also in the Iliad, when the River Scamander, indignant at the sight of so many corpses in his water, overflows and threatens to drown Achilles, the latter grasps a branch of a great elm in an attempt to save himself ("ὁ δὲ πτελέην ἕλε χερσὶν εὐφυέα μεγάλην".[62]

The Nymphs also planted elms on the tomb in the Thracian Chersonese of "great-hearted Protesilaus" ("μεγάθυμου Πρωτεσιλάου"), the first Greek to fall in the Trojan War. These elms grew to be the tallest in the known world; but when their topmost branches saw far off the ruins of Troy, they immediately withered, so great still was the bitterness of the hero buried below, who had been loved by Laodamia and slain by Hector.[63][64][65] The story is the subject of a poem by Antiphilus of Byzantium (1st century AD) in the Palatine Anthology:

- Θεσσαλὲ Πρωτεσίλαε, σὲ μὲν πολὺς ᾄσεται αἰών,

- Tρoίᾳ ὀφειλoμένoυ πτώματος ἀρξάμενoν•

- σᾶμα δὲ τοι πτελέῃσι συνηρεφὲς ἀμφικoμεῦση

- Nύμφαι, ἀπεχθoμένης Ἰλίoυ ἀντιπέρας.

- Δένδρα δὲ δυσμήνιτα, καὶ ἤν ποτε τεῖχoς ἴδωσι

- Tρώϊον, αὐαλέην φυλλοχoεῦντι κόμην.

- ὅσσoς ἐν ἡρώεσσι τότ᾽ ἦν χόλoς, oὗ μέρoς ἀκμὴν

- ἐχθρὸν ἐν ἀψύχoις σώζεται ἀκρέμoσιν.[66]

- [:Thessalian Protesilaos, a long age shall sing your praises,

- Of the destined dead at Troy the first;

- Your tomb with thick-foliaged elms they covered,

- The nymphs, across the water from hated Ilion.

- Trees full of anger; and whenever that wall they see,

- Of Troy, the leaves in their upper crown wither and fall.

- So great in the heroes was the bitterness then, some of which still

- Remembers, hostile, in the soulless upper branches.]

Protesilaus had been king of Pteleos (Πτελεός) in Thessaly, which took its name from the abundant elms (πτελέoι) in the region.[67]

Elms occur often in pastoral poetry, where they symbolise the idyllic life, their shade being mentioned as a place of special coolness and peace. In the first Idyll of Theocritus (3rd century BC), for example, the goat-herd invites the shepherd to sit "here beneath the elm" ("δεῦρ' ὑπὸ τὰν πτελέαν") and sing. Beside elms Theocritus places "the sacred water" ("το ἱερὸν ὕδωρ") of the Springs of the Nymphs and the shrines to the nymphs.[68]

Aside from references literal and metaphorical to the elm and vine theme, the tree occurs in Latin literature in the Elm of Dreams in the Aeneid.[69] When the Sibyl of Cumae leads Aeneas down to the Underworld, one of the sights is the Stygian Elm:

- In medio ramos annosaque bracchia pandit

- ulmus opaca, ingens, quam sedem somnia vulgo

- uana tenere ferunt, foliisque sub omnibus haerent.

- [:Spreads in the midst her boughs and agéd arms

- an elm, huge, shadowy, where vain dreams, 'tis said,

- are wont to roost them, under every leaf close-clinging.]

Virgil refers to a Roman superstition (vulgo) that elms were trees of ill-omen because their fruit seemed to be of no value.[70] It has been noted[71] that two elm-motifs have arisen from classical literature: (1) the 'Paradisal Elm' motif, arising from pastoral idylls and the elm-and-vine theme, and (2) the 'Elm and Death' motif, perhaps arising from Homer's commemorative elms and Virgil's Stygian Elm. Many references to elm in European literature from the Renaissance onwards fit into one or other of these categories.

There are two examples of pteleogenesis (:birth from elms) in world myths. In Germanic and Scandinavian mythology the first woman, Embla, was fashioned from an elm,[72] while in Japanese mythology Kamuy Fuchi, the chief goddess of the Ainu people, "was born from an elm impregnated by the Possessor of the Heavens".[73]

The elm occurs frequently in English literature, one of the best known instances being in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, where Titania, Queen of the Fairies, addresses her beloved Nick Bottom using an elm-simile. Here, as often in the elm-and-vine motif, the elm is a masculine symbol:

- Sleep thou, and I will wind thee in my arms.

- ... the female Ivy so

- Enrings the barky fingers of the Elm.

- O, how I love thee! how I dote on thee![74]

Another of the most famous kisses in English literature, that of Paul and Helen at the start of Forster's Howards End, is stolen beneath a great wych elm.

The elm tree is also referenced in children's literature. An Elm Tree and Three Sisters by Norma Sommerdorf is a children's book about three young sisters that plant a small elm tree in their backyard.[75]

In politics

The cutting of the elm was a diplomatic altercation between the Kings of France and England in 1188, during which an elm tree near Gisors in Normandy was felled. [76]

In politics the elm is associated with revolutions. In England after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the final victory of parliamentarians over monarchists, and the arrival from Holland, with William III and Mary II, of the 'Dutch Elm' hybrid, planting of this cultivar became a fashion among enthusiasts of the new political order.[77][78]

In the American Revolution 'The Liberty Tree' was an American white elm in Boston, Massachusetts, in front of which, from 1765, the first resistance meetings were held against British attempts to tax the American colonists without democratic representation. When the British, knowing that the tree was a symbol of rebellion, felled it in 1775, the Americans took to widespread 'Liberty Elm' planting, and sewed elm symbols on to their revolutionary flags.[79][80] Elm-planting by American Presidents later became something of a tradition.

In the French Revolution, too, Les arbres de la liberté (:Liberty Trees), often elms, were planted as symbols of revolutionary hopes, the first in Vienne, Isère, in 1790, by a priest inspired by the Boston elm.[79] L'Orme de La Madeleine (:the Elm of La Madeleine), Faycelles, Département de Lot, planted around 1790 and surviving to this day, was a case in point.[81] By contrast, a famous Parisian elm associated with the Ancien Régime, L'Orme de Saint-Gervais in the Place St-Gervais, was felled by the revolutionaries; church authorities planted a new elm in its place in 1846, and an early 20th-century elm stands on the site today.[82] Premier Lionel Jospin, obliged by tradition to plant a tree in the garden of the Hôtel Matignon, the official residence and workplace of Prime Ministers of France, insisted on planting an elm, so-called 'tree of the Left', choosing the new disease-resistant hybrid 'Clone 762' (Ulmus 'Wanoux' = Vada).[83] In the French Republican Calendar, in use from 1792 to 1806, the 12th day of the month Ventôse (= 2 March) was officially named "jour de l'Orme", Day of the Elm.

Liberty Elms were also planted in other countries in Europe to celebrate their revolutions, an example being L'Olmo di Montepaone, L'Albero della Libertà (:the Elm of Montepaone, Liberty Tree) in Montepaone, Calabria, planted in 1799 to commemorate the founding of the democratic Parthenopean Republic, and surviving until it was brought down by a recent storm (it has since been cloned and 'replanted').[84] After the Greek Revolution of 1821–32, a thousand young elms were brought to Athens from Missolonghi, "Sacred City of the Struggle" against the Turks and scene of Lord Byron's death, and planted in 1839–40 in the National Garden.[85][86] In an ironic development, feral elms have spread and invaded the grounds of the abandoned Greek royal summer palace at Tatoi in Attica.

In a chance event linking elms and revolution, on the morning of his execution (30 January 1649), walking to the scaffold at the Palace of Whitehall, King Charles I turned to his guards and pointed out, with evident emotion, an elm near the entrance to Spring Gardens that had been planted by his brother in happier days. The tree was said to be still standing in the 1860s.[87]

Planting a Liberty Tree (un arbre de la liberté) during the French Revolution. Jean-Baptiste Lesueur, 1790

Planting a Liberty Tree (un arbre de la liberté) during the French Revolution. Jean-Baptiste Lesueur, 1790 Balcony with elm symbol, overlooking the 'Crossroads of the Elm', Place Saint-Gervais, Paris[82]

Balcony with elm symbol, overlooking the 'Crossroads of the Elm', Place Saint-Gervais, Paris[82] President George W. Bush and Laura Bush planting a disease-resistant 'Jefferson' Elm before the White House, 2006

President George W. Bush and Laura Bush planting a disease-resistant 'Jefferson' Elm before the White House, 2006- Elm suckers spreading before the abandoned summer royal palace in Tatoi, Greece, Μarch 2008

In local history and place names

The name of what is now the London neighborhood of Seven Sisters is derived from seven elms which stood there at the time when it was a rural area, planted a circle with a walnut tree at their centre, and traceable on maps back to 1619.[88][89]

Propagation

Elm propagation methods vary according to elm type and location, and the plantsman's needs. Native species may be propagated by seed. In their natural setting native species, such as wych elm and European White Elm in central and northern Europe and field elm in southern Europe, set viable seed in ‘favourable' seasons. Optimal conditions occur after a late warm spring.[1] After pollination, seeds of spring-flowering elms ripen and fall at the start of summer (June); they remain viable for only a few days. They are planted in sandy potting-soil at a depth of one centimetre, and germinate in three weeks. Slow-germinating American Elm will remain dormant until the second season.[90] Seeds from autumn-flowering elms ripen in the Fall and germinate in the spring.[90] Since elms may hybridize within and between species, seed-propagation entails a hybridisation risk. In unfavourable seasons elm seeds are usually sterile. Elms outside their natural range, such as Ulmus procera in England, and elms unable to pollinate because pollen-sources are genetically identical, are sterile and are propagated by vegetative reproduction. Vegetative reproduction is also used to produce genetically identical elms (clones). Methods include the winter transplanting of root-suckers; taking hardwood cuttings from vigorous one-year-old shoots in late winter,[91] taking root-cuttings in early spring; taking softwood cuttings in early summer;[92] grafting; ground and air layering; and micropropagation. A bottom heat of 18 degrees[93] and humid conditions are maintained for hard- and softwood cuttings. The transplanting of root-suckers remains the easiest and commonest propagation-method for European field elm and its hybrids. For 'specimen' urban elms, grafting to wych-elm root-stock may be used to eliminate suckering or to ensure stronger root-growth. The mutant-elm cultivars are usually grafted, the ‘weeping' elms 'Camperdown' and 'Horizontalis' at 2–3 m (6 ft 7 in–9 ft 10 in), the dwarf cultivars 'Nana' and 'Jacqueline Hillier' at ground level. Since the Siberian Elm is drought-tolerant, in dry countries new varieties of elm are often root-grafted on this species.[94]

Ripe seeds of field elm

Ripe seeds of field elm- Rock elm Ulmus thomasii germinating

Seedling of wych elm Ulmus glabra (photograph: Mihailo Grbić)

Seedling of wych elm Ulmus glabra (photograph: Mihailo Grbić) Root-suckers spreading from field elm Ulmus minor

Root-suckers spreading from field elm Ulmus minor Root cuttings of Ulmus 'Dodoens' (photograph: Mihailo Grbić)

Root cuttings of Ulmus 'Dodoens' (photograph: Mihailo Grbić) Rooted hardwood elm-cutting (photograph: Mihailo Grbić)

Rooted hardwood elm-cutting (photograph: Mihailo Grbić) Rooting of softwood elm-cuttings under mist-propagation system (photograph: Mihailo Grbić)

Rooting of softwood elm-cuttings under mist-propagation system (photograph: Mihailo Grbić) Mutant variegated Smooth-leafed Elm graft (photograph: Mihailo Grbić)

Mutant variegated Smooth-leafed Elm graft (photograph: Mihailo Grbić)

In vitro propagation of Ulmus chenmoui by bud meristem (photograph: Mihailo Grbić)

In vitro propagation of Ulmus chenmoui by bud meristem (photograph: Mihailo Grbić)._Royal_Terrace%2C_Edinburgh_(5).jpg) Aerial roots, hybrid elm cultivar

Aerial roots, hybrid elm cultivar

Organisms associated with elm

'Pouch' leaf-galls on a wych elm (aphid Tetraneura ulmi), Germany.

'Pouch' leaf-galls on a wych elm (aphid Tetraneura ulmi), Germany._gall%2C_Elst_(Gld)%2C_the_Netherlands.jpg) 'Pouch' leaf-gall on elm leaf (aphid Tetraneura ulmi), Netherlands.

'Pouch' leaf-gall on elm leaf (aphid Tetraneura ulmi), Netherlands. 'Cockscomb' leaf-galls (aphid Colopha compressa), Poland.

'Cockscomb' leaf-galls (aphid Colopha compressa), Poland.- 'Bladder' leaf-galls on elm leaves (aphid Eriosoma lanuginosum), Italy.

- 'Bladder' leaf-galls on a narrow-leaved elm (aphid Eriosoma lanuginosum), Italy.

Aphids in leaf-gall, Poland.

Aphids in leaf-gall, Poland. 'Pimple' leaf-galls on a field elm (mite Eriophyes ulmi), Spain.

'Pimple' leaf-galls on a field elm (mite Eriophyes ulmi), Spain.- White-letter Hairstreak Satyrium w-album, on Lutece, Sweden. The larvae feed only on elm.

Egg of Satyrium w-album near flower-bud of an elm.

Egg of Satyrium w-album near flower-bud of an elm. Elm-bark beetle Scolytus multistriatus (size: 2–3 mm), a vector for Dutch Elm Disease

Elm-bark beetle Scolytus multistriatus (size: 2–3 mm), a vector for Dutch Elm Disease Scolytus multistriatus 'galleries' under elm-bark.

Scolytus multistriatus 'galleries' under elm-bark.- Elm-leaf beetle Xanthogaleruca luteola, which causes serious damage to elm foliage.

Xanthogaleruca luteola: caterpillar on elm-leaf, Germany.

Xanthogaleruca luteola: caterpillar on elm-leaf, Germany. Elm-leaf damage caused by Xanthogaleruca luteola, Germany.

Elm-leaf damage caused by Xanthogaleruca luteola, Germany. Bacterial infection Erwinia carotovora of elm sap, which causes 'slime flux' ('wetwood') and staining of the trunk (here on a Camperdown Elm).

Bacterial infection Erwinia carotovora of elm sap, which causes 'slime flux' ('wetwood') and staining of the trunk (here on a Camperdown Elm).

See also

- Elm Conflict

- List of Elm cultivars, hybrids and hybrid cultivars

- List of Elm species and varieties by scientific name

- List of Lepidoptera that feed on elms

- Fab Tree Hab

References

- Richens, R. H. (1983). Elm. Cambridge University Press.

- Flora of Israel Online: Ulmus minor Mill. | Flora of Israel Online, accessdate: July 28, 2020

- Fu, L., Xin, Y. & Whittemore, A. (2002). Ulmaceae, in Wu, Z. & Raven, P. (eds) Flora of China Archived 10 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 5 (Ulmaceae through Basellaceae). Science Press, Beijing, and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, US.

- Rackham, Oliver (1980). Ancient woodland: its history, vegetation and uses. Edward Arnold, London

- Bean, W. J. (1981). Trees and shrubs hardy in Great Britain, 7th edition. Murray, London

- Brummitt, R. K. (1992). Vascular Plant Families & Genera. Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, London, UK.

- Marren, Peter, Woodland Heritage (Newton Abbot, 1990).

- Werthner, William B. (1935). Some American Trees: An intimate study of native Ohio trees. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. xviii + 398.

- Heybroek, H. M., Goudzwaard, L, Kaljee, H. (2009). Iep of olm, karakterboom van de Lage Landen (:Elm, a tree with character of the Low Countries). KNNV, Uitgeverij. ISBN 9789050112819

- Edlin, H. L. (1947). British Woodland Trees, p.26. 3rd. edition. London: B. T. Batsford Ltd.

- Webber, J. (2019). What have we learned from 100 years of Dutch Elm Disease? Quarterly Journal of Forestry. October 2019, Vol. 113, No.4, p.264-268. Royal Forestry Society, UK.

- Brasier, C. M. & Mehotra, M. D. (1995). Ophiostoma himal-ulmi sp. nov., a new species of Dutch elm disease fungus endemic to the Himalayas. Mycological Research 1995, vol. 99 (2), 205–215 (44 ref.) ISSN 0953-7562. Elsevier, Oxford, UK.

- Brasier, C. M. (1996). New horizons in Dutch elm disease control. Pages 20-28 in: Report on Forest Research Archived 28 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, 1996. Forestry Commission. HMSO, London, UK.

- "Elm Yellows Archived 4 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine". Elmcare.Com. 19 Mar. 2008.

- Price, Terry. "Wilt Diseases Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine". Forestpests.Org. 23 Mar. 2005. 19 Mar. 2008.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Burdekin, D.A.; Rushforth, K.D. (November 1996). Revised by J.F. Webber. "Elms resistant to Dutch elm disease" (PDF). Arboriculture Research Note. Alice Holt Lodge, Farnham: Arboricultural Advisory & Information Service. 2/96: 1–9. ISSN 1362-5128. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- Ware, G. (1995). Little-known elms from China: landscape tree possibilities. Journal of Arboriculture Archived 30 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine, (Nov. 1995). International Society of Arboriculture, Champaign, Illinois, US.

- Biggerstaffe, C., Iles, J. K., & Gleason, M. L. (1999). Sustainable urban landscapes: Dutch elm disease and disease-resistant elms. SUL-4, Iowa State University

- Sticklen, Mariam B.; Sherald, James L. (1993). Chapter 13: Strategies for the Production of Disease-Resistant Elms. Mariam B.; Sherald, James L. (eds.). Dutch Elm Disease Research: Cellular and Molecular Approaches. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 171–183. ISBN 9781461568728. LCCN 93017484. OCLC 851736058. Retrieved 22 November 2019 – via Google Books.

- Newhouse, AE; Schrodt, F; Liang, H; Maynard, CA; Powell, WA (2007). "Transgenic American elm shows reduced Dutch elm disease symptoms and normal mycorrhizal colonization". Plant Cell Rep. 26 (7): 977–987. doi:10.1007/s00299-007-0313-z. PMID 17310333.

- Martín-Benito D., Concepción García-Vallejo M., Pajares J. A., López D. 2005. "Triterpenes in elms in Spain Archived 28 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine". Can. J. For. Res. 35: 199–205 (2005).

- Pajares, J. A., García, S., Díez, J. J., Martín, D. & García-Vallejo, M. C. 2004. "Feeding responses by Scolytus scolytus to twig bark extracts from elms Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine". Invest Agrar: Sist Recur For. 13: 217–225.

- Martín, JA; Solla, A; Venturas, M; Collada, C; Domínguez, J; Miranda, E; Fuentes, P; Burón, M; Iglesias, S; Gil, L (1 April 2015). "Seven Ulmus minor clones tolerant to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi registered as forest reproductive material in Spain". IForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry. Italian Society of Sivilculture and Forest Ecology (SISEF). 8 (2): 172–180. doi:10.3832/ifor1224-008. ISSN 1971-7458.

- "Scientific Name: Ulmus x species" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Santini A., Fagnani A., Ferrini F., Mittempergher L., Brunetti M., Crivellaro A., Macchioni N., "Elm breeding for DED resistance, the Italian clones and their wood properties Archived 26 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine". Invest Agrar: Sist. Recur. For (2004) 13 (1), 179–184. 2004.

- Santamour, J., Frank, S. & Bentz, S. (1995). Updated checklist of elm (Ulmus) cultivars for use in North America. Journal of Arboriculture, 21:3 (May 1995), 121–131. International Society of Arboriculture, Champaign, Illinois, US

- Smalley, E. B. & Guries, R. P. (1993). Breeding Elms for Resistance to Dutch Elm Disease. Annual Review of Phytopathology Vol. 31 : 325–354. Palo Alto, California

- Heybroek, Hans M. (1983). Burdekin, D.A. (ed.). "Resistant elms for Europe" (PDF). Forestry Commission Bulletin (Research on Dutch Elm Disease in Europe). London: HMSO (60): 108–113. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2017.

- Heybroek, H.M. (1993). "The Dutch Elm Breeding Program". In Sticklen, Mariam B.; Sherald, James L. (eds.). Dutch Elm Disease Research. New York, USA: Springer-Verlag. pp. 16–25. ISBN 978-1-4615-6874-2. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- Mittempergher, L; Santini, A (2004). "The history of elm breeding" (PDF). Investigacion Agraria: Sistemas y Recursos Forestales. 13 (1): 161–177. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2017.

- Martin, J., Sobrina-Plata, J., Rodriguez-Calcerrada, J., Collada, C., and Gil, L. (2018). Breeding and scientific advances in the fight against Dutch elm disease: Will they allow the use of elms in forest restoration? New Forests, 1-33. Springer Nature 2018.

- Mittempergher, L., (2000). Elm Yellows in Europe. In: The Elms, Conservation and Disease Management. pp. 103-119. Dunn C.P., ed. Kluwer Academic Press Publishers, Boston, USA.

- Brookes, A. H. (2013). Disease-resistant elm cultivars, Butterfly Conservation trials report, 2nd revision, 2013. Butterfly Conservation, Hants & IoW Branch, England. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Elwes, H. J. & Henry, A. (1913). The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Vol. VII. 1848–1929. Republished 2004 Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781108069380

- Edlin, H. L., Guide to Tree Planting and Cultivation (London, 1970), p.330, p.316

- 'Salt-tolerant landscape plants', countyofdane.com/myfairlakes/A3877.pdf

- dutchtrig.com/the_netherlands/the_hague.html

- Hiemstra, J.A.; et al. (2007). Belang en toekomst van de iep in Nederland [Importance and future of the elm in the Netherlands]. Wageningen, Netherlands: Praktijkonderzoek Plant & Omgeving B.V. Archived from the original on 28 September 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- Central Park Conservancy. The Mall and Literary Walk Archived 10 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Pollak, Michael. The New York Times. "Answers to Questions About New York Archived April 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine." 11 January 2013.

- Sherald, James L (December 2009). Elms for the Monumental Core: History and Management Plan (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Center for Urban Ecology, National Capital Region, National Park Service. Natural Resource Report NPS/NCR/NRR--2009/001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, Documents in Mycaenean Greek, Cambridge 1959

- Hesiod, Works and Days, 435

- Elm Archived 3 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Niche Timbers. Accessed 19-08-2009.

- Columella, De Re Rustica

- Ovid, Amores 2.16.41

- Virgil, Georgica, I.2: ulmis adiungere vites (:to marry vines to elms); Horace, Epistolae 1.16.3: amicta vitibus ulmo (:the elm clothed in the vine); and Catullus, Carmina, 62

- Braun, Lesley; Cohen, Marc (2006). Herbs and Natural Supplements: An Evidence-Based Guide (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone. p. 586. ISBN 978-0-7295-3796-4., quote:"Although Slippery Elm has not been scientifically investigated, the FDA has approved it as a safe demulcent substance."

- Maunder, M. (1988). Plants in Peril, 3. Ulmus wallichiana (Ulmaceae). Kew Magazine. 5(3): 137-140. Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, London.

- Santini, A., Pecori, F., Pepori, A. L., Ferrini, F., Ghelardini, L. (In press). Genotype × environment interaction and growth stability of several elm clones resistant to Dutch elm disease. Forest Ecology and Management. Elsevier B. V., Netherlands.

- Osborne, P. (1983). The influence of Dutch elm disease on bird population trends. Bird Study, 1983: 27-38.

- D. S. Vohra (1 June 2004). Bach Flower Remedies: A Comprehensive Study. B. Jain Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-7021-271-3. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- Solla, A., Bohnens, J., Collin, E., Diamandis, S., Franke, A., Gil, L., Burón, M., Santini, A., Mittempergher, L., Pinon, J., and Vanden Broeck, A. (2005). Screening European Elms for Resistance to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi. Forest Science 51(2) 2005. Society of American Foresters, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

- Pinon J., Husson C., Collin E. (2005). Susceptibility of native French elm clones to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi. Annals of Forest Science 62: 1–8

- Collin, E. (2001). Elm. In Teissier du Cros (Ed.) (2001) Forest Genetic Resources Management and Conservation. France as a case study. Min. Agriculture, Bureau des Ressources Genetiques CRGF, INRA-DIC, Paris: 38–39.

- Johannes Christiaan Karel Klinkenberg Archived 21 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Athenaeus, Δειπνοσοφισταί, III

- Callimachus, Hymn to Artemis, 120-121 [:'First at an elm, and second at an oak didst thou shoot, and third again at a wild beast']. theoi.com/Text/CallimachusHymns1.html

- Iliad, Ζ, 419–420, www.perseus.tufts.edu Archived 26 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Iliad, Φ, 242–243, www.perseus.tufts.edu Archived 26 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Philostratus, ̔Ηρωικός, 3,1 perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2008.01.0597%3Aolpage%3D672

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Τα μεθ' `Ομηρον, 7.458–462

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 16.88

- Anth. Pal., 7.141

- Lucas, F. L., From Olympus to the Styx (London, 1934)

- Theocritus, Eιδύλλιo I, 19–23; VII, 135–40

- Vergil, Aeneid, VI. 282–5

- Richens, R. H., Elm (Cambridge 1983) p.155

- Richens, R. H., Elm, Ch.10 (Cambridge, 1983)

- Heybroek, H. M., 'Resistant Elms for Europe' (1982) in Research on Dutch Elm Disease in Europe, HMSO, London 1983

- Wilkinson, Gerald, Epitaph for the Elm (London, 1978), p.87

- Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Act 4, Scene 1

- Janssen, Carolyn. "An elm tree and three sisters (Book Review)". ebscohost. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- "Priory of Sion". Crystalinks. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Rackham, O. (1976). Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape J. M. Dent, London.

- Armstrong, J. V.; Sell, P. D. (1996). "A revision of the British elms (Ulmus L., Ulmaceae): the historical background". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 120: 39–50. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1996.tb00478.x. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- Richens, Elm (Cambridge, 1983)

- elmcare.com/about_elms/history/liberty_elm_boston.htm

- L'Orme de La Madeleine, giuseppemusolino.it Archived 26 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- L'Orme de St-Gervais: biographie d'un arbre, www.paris.fr Archived 6 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Ulmus 'Wanoux' (Vada)) freeimagefinder.com/detail/6945514690.html

- calabriaonline.com Archived 30 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Ο μοναδικός Εθνικός μας Κήπος, paidevo.gr/teachers/?p=859

- Νίκος Μπελαβίλας, ΜΥΘΟΙ ΚΑΙ ΠΡΑΓΜΑΤΙΚΟΤΗΤΕΣ ΓΙΑ ΤΟ ΜΗΤΡΟΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΟ ΠΑΡΚΟ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟΥ, courses.arch.ntua.gr/fsr/112047/Nikos_Belavilas-Mythoi_kai_Pragmatikotites

- Elizabeth and Mary Kirby, Talks about Trees: a popular account of their nature and uses, 3rd edn., p.97-98 (1st edn. titled Chapters on Trees: a popular account of their nature and uses, London, 1873)

- Tottenham: Growth before 1850', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 5: Hendon, Kingsbury, Great Stanmore, Little Stanmore, Edmonton Enfield, Monken Hadley, South Mimms, Tottenham (1976)

- "London Gardens Online". www.londongardensonline.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- forestry.about.com/od/treeplanting/qt/seed_elm.htm

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- cru.cahe.wsu.edu/CEPublications/pnw0152/pnw0152.html

- resistantelms.co.uk/elms/ulmus-morfeo/

- Clouston, B., Stansfield, K., eds., After the Elm (London, 1979)

Monographs

- Richens, R. H. (1983). Elm. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24916-3. A scientific, historical and cultural study, with a thesis on elm-classification, followed by a systematic survey of elms in England, region by region. Illustrated.

- Heybroek, H. M., Goudzwaard, L, Kaljee, H. (2009). Iep of olm, karakterboom van de Lage Landen (:Elm, a tree with character of the Low Countries). KNNV, Uitgeverij. ISBN 9789050112819. A history of elm planting in the Netherlands, concluding with a 40 – page illustrated review of all the DED – resistant cultivars in commerce in 2009.

Further reading

- Clouston, B.; Stansfield, K., eds. (1979). After the Elm. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-13900-9. A general introduction, with a history of Dutch elm disease and proposals for re-landscaping in the aftermath of the pandemic. Illustrated.

- Coleman, M., ed. (2009). Wych Elm. Edinburgh. ISBN 978-1-906129-21-7. A study of the species, with particular reference to the wych elm in Scotland and its use by craftsmen.

- Dunn, Christopher P. (2000). The Elms: Breeding, Conservation, and Disease-Management. New York: Boston, Mass. Kluwer academic. ISBN 0-7923-7724-9.

- Wilkinson, G. (1978). Epitaph for the Elm. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-921280-3. A photographic and pictorial celebration and general introduction.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ulmus. |

- "Elm trials". Northern Arizona University.

- Tree Family Ulmaceae Diagnostic photos of Elm species at the Morton Arboretum

- "Late 19th and early 20th-century photos of Elm species in Elwes & Henry's Trees of Great Britain & Ireland, v. 7" (PDF). 1913.

- "Elm Photo Gallery".

- Eichhorn, Markus (May 2010). "Elm – The Tree of Death". Test Tube. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- "Elm". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Elm". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Elm". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.