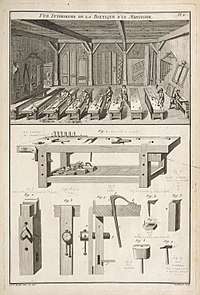

Workbench (woodworking)

A workbench is a table used by woodworkers to hold workpieces while they are worked by other tools. There are many styles of woodworking benches, each reflecting the type of work to be done or the craftsman's way of working. Most benches have two features in common: they are heavy and rigid enough to keep still while the wood is being worked, and there is some method for holding the work in place at a comfortable position and height so that the worker is free to use both hands on the tools. The main thing that distinguishes benches is the way in which the work is held in place. Most benches have more than one way to do this, depending on the operation being performed.

Holding the work

Planing stop

Probably the oldest and most basic method of holding the work is a planing stop or dog ear, which is simply a peg or small piece of wood or metal that stands just above the surface at the end of the bench top. The work is placed on the bench with the end pushed against the stop. The force of the planing keeps the board in place, so long as the force is always toward the stop. Planing against a stop gives the woodworker good feedback - they can tell a lot about what is going on just by the pressure, force and balance required. A stop can take the form of a batten attached to the end of the bench, or it can be adjustable, able to be moved up and down according to the size of the work - or pushed down below the surface when not needed. A simple bench dog can serve as a planing stop.

Hold fast

Another ancient method of holding the work is the hold fast or holdfast. A holdfast looks like a shepherd's crook. The shank goes into a hole in the bench top and the tip of the hook is pressed against the work from above. The holdfast is set by rapping the top with a mallet, and released by hitting the back side. A good holdfast works remarkably well, and is inexpensive and easy to install.

The holdfast can also be used for clamping work to the side of the bench for jointing. If the legs on your base are not too far under the top, simply bore a hole in the side of the leg and use the holdfast horizontally. A woodworker can do just about anything they need on a bench with only a planing stop and a holdfast or two.

Hardpoints

It is common to have holes in the benchtop that tools or jigs can be bolted to. In applications where repeated removal and reinstallation of the tool or jig is desirable, screwing into the wood of the benchtop with woodscrews or lag bolts is not an ideal solution, because the wooden threads don't lend themselves to repeated disassembly and reassembly. In such cases, it is useful to create hardpoints, which are metal threads embedded in the wood. These hardpoints make repeated disassembly and reassembly trouble-free. They are essentially nuts that are embedded into the wood in one way or another. T-nuts (aka tee nuts) are an easy way to create a hardpoint. Custom nuts similar to T-nuts but with holes for woodscrews in place of the spikes are sometimes machined for the purpose.

Vises

Long ago, just as today, woodworkers required a more helpful way to keep the wood in place while it was being worked. A device was needed that could be used effectively on different sizes of wood. Probably the first such device used two stops - at least one of which was adjustable for position - and wedges between them and the work to fix it in place. This is still a cheap and effective method for holding the work.

A screw is really just a wedge in the round. Today, most vises use a big screw to apply the clamping force. The vise is often used to hold objects in place when working on a piece.

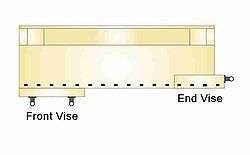

There are two main categories of vise (vice in UK English sp.) : vises on the end of the bench and vises on the front of the bench. End vises (also called 'tail vises') are usually mounted on the right side of the bench for right-handed workers. They can typically hold work in two ways: between the jaws and along the top of the bench using moveable 'dogs' in place of jaws. Not all benches have tail vises. A front vise (also called 'face vise' or 'shoulder vise') is typically mounted on the left front side of the bench. They may be used for holding a board to be edge jointed, or sometimes for sawing out dovetails and the like.

Front vises

Leg vise

Probably the oldest front vise design is the leg vise. It's called a leg vise because one of the bench's legs is an integral part of it - usually forming the inside jaw. The outside jaw also goes all the way to the floor - or nearly so. There is a single screw mounted between a quarter and a third of the way down that goes through both jaws with the nut on the back of the leg. Finally, there is some sort of horizontal beam at the bottom to act as a fulcrum. This beam may take the form of a board that can be adjusted by means of holes and pegs, or it can even be another screw. The leg vise is probably the simplest and least expensive of the front vises, and it is very strong.

Shoulder vise

Another old design is the shoulder vise. The best thing about this design is that it allows clamping directly behind the screw. This yields unobstructed vertical clamping for cutting dovetails and similar operations. There is also typically a little play in the screw/jaw attachment that provides for clamping of tapered work. This is one vise that should be designed into the bench from the beginning, as it is difficult to retrofit into an existing bench. The primary drawback of the shoulder vise is its fragility, unless the "arm" is attached to the "end cap" using a dovetail or finger joint, usually glued or "pinned" to eliminate rotative movement about the joint, otherwise it is fairly easy to break it with a big steel bench screw. But one should never really have to put that much force on it. Some woodworkers say that the big vise gets in the way of some jobs, others find it unobtrusive. Implicit in a shoulder vise is an integral planing stop, formed by the intersection of the jaw and the jaw spacer, and which allows the shoulder vise to perform multiple duties, such as jointing long boards with a "bench slave" to hold the opposite end. In earlier times, a crochet and a holdfast would perform the same function.

Hybrid vise

Many of the commercial European benches have a front vise that uses a wooden jaw with a metal screw and built-in anti-racking hardware. These vises are also available as inexpensive kits that can be mounted on almost any bench.

Quick-action vise

Perhaps the easiest face vise to install is the self-contained iron vise, sometimes called the 'quick-action' vise (except they are not all quick-action). This tool comes already assembled and only has to be mounted to the bench. Usually, auxiliary wooden jaws are added. The quick-action feature makes setting it much quicker and is quickly taken for granted. Not only are these vises easy to install and use, they are also robust. Their main drawback is the relatively high cost.

Patternmaker's vise

The patternmaker's vise is sometimes used as a front vise. This style was originally designed for patternmakers, the folks who make the forms used in metal casting. Pattern making is exacting work using shapes not normally encountered by a cabinetmaker. The patternmaker's vise can hold odd shapes at various angles, and it can certainly hold simple shapes at regular angles. The drawbacks of this vise are the expense, the moderately complicated mounting, and a tendency to fragility. The most sought-after is an antique Emmert, but there are several clones on the market today, including one by Lee Valley Tools that is made of an aluminum alloy—which should be less likely to break—and several from Taiwan and which are clones of the smaller Emmert. A possible disadvantage of the patternmaker's vise is it usually requires installation on a bench which is at least 1-3/4" thick

Twin-screw vise

This is another old design making a comeback thanks to Lee Valley's Veritas Toolworks. The twin-screw vise was popular during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, particularly with chair makers. The updated Veritas design uses a chain to connect the two screws, keeping them slaved to each other. There is also a provision for decoupling the screws so that tapered work can be held. This design has many of the advantages of the classic shoulder vise and single screw face vise, with few of the disadvantages. It can also be used effectively as an end vise. The main drawbacks of the twin-screw vise are the expense and the relatively difficult installation.

Front vise comparison

| Vise Type | Cost | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leg Vise | Low | Strong design Adaptable | Can be cumbersome to set Not good for those who dislike stooping |

| Shoulder Vise | Low | Work clamped directly under screw Can clamp work vertically Can handle tapered work It is theoretically possible to clamp workpieces which are as tall as the floor-to-ceiling distance | Relatively complex and potentially fragile design Bench slave or deadman required for jointing Shoulder gets in the way of some work |

| Hybrid Vise | Medium | Relatively wide face Wood clamping surfaces Can be made to fit a range of installations | Not ideal for vertical clamping Prone to racking |

| Quick Action Vise | Medium | Strong design Can be set one-handed quickly Relatively simple installation | Not ideal for vertical clamping Bench thickness critical |

| Pattern Maker's Vise | High | Most versatile Can clamp odd shapes at odd angles Can be retro-fitted to existing bench | Somewhat fragile Bench thickness critical |

| Twin Screw Vise (Used as front vise) | High | Very strong design Can clamp work vertically Good for jointing Can handle tapered work | Relatively difficult installation |

End vises

Traditional tail vise

The traditional tail vise uses one large screw, either wooden or metal. It is made in the form of a frame, with the back part of the frame fitting under the bench, and the movement of that frame located and restrained by a complex system of sliding tongues and grooves, and runners, such that smooth left and right movements of the frame are possible, but forward and backward movements, or rotative movements of the frame are impossible. The jaw has a face that contacts the bench top, and it has one or more dog holes on the top—often 3 to 4, each spaced 5 inches apart—that are in line with the dog holes located on the front face (apron) of the bench—numerous holes, each also spaced 5 inches apart. This is the least expensive option for a tail vise, but it is by far the most complex to design, construct and maintain. Tage Frid and Frank Klausz popularized this type of tail vise in North America, although its origin dates back to northern Europe (most probably Germany) in the 18th century.

Wagon or Enclosed Tail vise

This traditional tail vise also uses one large screw, either wooden or metal. It consists of a movable block with one or more dog holes in it, the movable block rides in a large mortise in the workbench. The jaw has a face that contacts the bench top, and the dog holes are in line with the dog holes on the bench top. The two main varieties of this vise depend on whether the screw nut is mounted in the bench or on the dog hole block. When the screw nut is mounted on the dog hole block the installation is more complicated and expensive, but the screw does not move in and out as the vise is used.

Modern tail vise

A newer form of tail vise does away with the need of a frame. It uses steel plates for its structure - one steel plate with the nut is mounted on the side of the bench, two others are built into a sliding jaw along with the bench screw. This is a robust design and it's easier to install and adjust than the older style. However, only a few sizes are commercially available (although larger sizes have been custom made).

Face vises as end vises

Some bench designers have adapted face vises for use as tail vises - with differing levels of success. Unfortunately, we are most likely to find the continental style vise used this way, and it's really least suited to the task. When used as a tail vise it has a strong tendency to "wrack" (twist or distort) because of the side forces. It isn't long before the hardware begins to show wear.

The steel quick-action vise doesn't suffer so much from this problem. With one exception, it functions well on the end of the bench. Its main drawback as a tail vise is the distance of the dog from the edge of the vise. Ideally, the dog hole strip should be fairly close to the edge of the bench. This puts your weight more directly over the work and behind the plane, enabling you to put more power and control into the operation with less strain. It is also important to keep the dog holes near the edge so that fenced planes can easily be used. With even a small quick-action vise the dog hole strip is still pretty far from the edge. So if you decide to use a quick-action vise as a tail vise, get the smallest good one you can find.

The twin-screw vise marketed by Lee Valley works well as a tail vise - that's really what it's designed for. The old wooden twin-screw design isn't suited for this task because there is no facility for holding the offside jaw open.

End vise comparison

| Vise Type | Cost | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Tail Vise | Low | Classic design Can be made with all wood parts | Relatively difficult to build and install Relatively fragile, unless constructed using dovetail or finger joints Unconstrained as to size and capacity It is theoretically possible to clamp workpieces which are as tall as the floor-to-ceiling distance, between the jaw and the apron |

| Wagon Vise/Enclosed Tail Vise (Nut in Bench Top) | Low | Strong design Can work on top of vise without damaging the mechanism Can be made with all wood parts | Cannot clamp large workpieces in the jaw Screw can get in the way when clamping long pieces Not good for pulling things apart |

| Wagon Vise/Enclosed Tail Vise (Nut in Movable Dog Hole Block) | High | Very strong design Can work on top of vise without damaging the mechanism Screw never projects out of the bench | Cannot clamp large workpieces in the jaw Relatively difficult installation |

| Leg Vise (Used as end vise) | Low | Strong design Can handle tapered work | Can be difficult to align Can be cumbersome to set Not good for those who dislike stooping |

| Hybrid Vise (Used as end vise) | Medium | Relatively easy installation Can be made to fit a range of installations | Not particularly suited to this application Prone to severe racking and wear |

| Quick Action Vise (Used as end vise) | Medium | Can be set one-handed quickly Relatively simple installation | Bench thickness critical Puts dog hole strip farther from the bench edge |

| Modern Tail Vise | High | Strong design Easier to install and align | Some construction still required for the "core", about which are mounted the steel slides, and in which are located the dog holes Only a few sizes of steel slides are commercially available (about 15" and about 19"), but other sizes have been custom made |

| Twin Screw Vise (Used as end vise) | High | Very strong design adaptable for multiple dog hole strips | Relatively difficult installation |

A planing stop

A planing stop A hold fast being used to affix a board to the benchtop for chiseling dovetails

A hold fast being used to affix a board to the benchtop for chiseling dovetails A simple vise using dogs and wedges (the wedges are colored for clarity)

A simple vise using dogs and wedges (the wedges are colored for clarity)- A leg vise

A board clamped in a traditional shoulder vise

A board clamped in a traditional shoulder vise A hybrid vise

A hybrid vise An easy to install self-contained iron vise

An easy to install self-contained iron vise A patternmaker's vise

A patternmaker's vise The Veritas twin-screw vise

The Veritas twin-screw vise A traditional tail vise

A traditional tail vise A modern tail vise

A modern tail vise A quick-action vise used as an end vise

A quick-action vise used as an end vise

Construction materials

Most workbenches are made from solid wood; the most expensive and desirable are made of solid hardwood. Benches may also be made from plywood and Masonite or hardboard, and bases of treated pine and even steel. There are trade offs with the choice of construction material. Solid wood has many advantages including strength, workability, appearance. A plywood or hardboard bench top has the advantage of being stable, relatively inexpensive, and in some ways it's easier to work with—particularly for a woodworker who doesn't yet have hand tools. The practical drawbacks of a plywood or composite bench top are that they don't hold their corners and edges well, and they can't be resurfaced with a plane—something that is needed from time to time.

Workbenches are fairly forgiving in the choice of wood. Maple, cherry, mahogany, or pine rarely give problems. Beech, oak, walnut, and fir make good benches. Benches are occasionally made using more exotic woods like purpleheart and teak, though the cost is high. The choice of wood is not as important as the integrity of the design—cross grain construction and inadequate joinery typically have a more destructive effect than the use of a less-than-ideal wood.

One popular and cheap source for bench top material is old bowling alley lanes. These are usually made from thick, high-quality laminated maple. Two problems present themselves with bowling alley wood: first, the waxes used on the surface for bowling frequently contain silicone and other substances that can play havoc with work pieces at finishing time—a little silicone on a project will cause trouble with many finishes, and won't manifest itself until it's too late. The other problem with bowling alley wood is nails. Most pieces have loads of nails buried in them, which do not mix well with woodworking tools. Such nails may be mitigated by using a metal detecting wand during stock preparation.

Many benches use different species of woods together. Small business woodworkers who work in a store-front sometimes use various species so that their clients can see examples of the different woods in a finished state. If this is done, it is important to use woods that are compatible with each other, particularly in the area of relative movement. Otherwise changes in temperature and humidity will stress the structure out of shape or it may even break.

The most common use for exotic woods in bench construction is for auxiliary parts such as oil cups, bench dogs, vise handles, sawing stops and the parts of wooden vises.

Size and positioning

The optimum size of a bench depends on the work to be done, space considerations, and budget. In general, bigger is better - though most woodworkers find that most work is done on the front few inches of the top, and then mostly in the front vise or right around the tail vise. So a smaller, narrow bench isn't as much of a drawback as might be expected - and it is far better than no bench at all. Tage Frid's classic bench is relatively small and it is one of the most copied designs. A big disadvantage of a smaller bench is that they are usually too light to resist heavy work without skidding around - but this problem can be overcome by attaching the bench to the floor.

Woodworkers seem to be evenly divided on the subject of bench positioning. Some like to be able to access their benches from all sides, while others like their bench against a wall. The advantage of wall placement - besides the saved space - is that tools can be stored on the wall over the bench, within easy reach. This keeps the tool storage out of the way, and the tools can still be reached without turning around or bending down.

The base

A workbench base should support the top so that it doesn't move, while at the same time keeping clear of the work. There are two main types: open bases and bases with built in storage. Open bases are easier to build and there is less chance of the base hindering the work - plus, it is usually necessary to compromise the strength and rigidity of a base in order to accommodate storage.

Probably the most popular style is the sled-foot trestle base. With this design, each pair of legs is put together in the form of an 'I' with two vertical bars. The leg pairs are connected by a pair of stretchers. These stretchers can be permanently fixed to the leg-pairs, or they can be made removable with tusk tenons or a bed-bolt arrangement. One of the advantages of this style is that there is no end-grain resting on the floor, so the legs are not as prone to wick-up moisture and rot.

Another popular style is a simple post and rail table structure. This is probably best implemented in heavy gauge steel, as wood doesn't really give enough resistance to the side forces that develop during heavy work. Most woodworkers who use this style with wood end up making another base before very long.

A hybrid design of the sled-foot trestle and the post and rail styles can work well. Instead of an 'I' structure, the sled foot is moved up to become a rail - sort of an 'H' with a bar across the top. This puts end-grain on the floor, but it is otherwise a strong design and somewhat easier to build. Plus, the feet don't get in the way of the work as sled-feet sometimes do.

Cast iron leg kits are available for woodworkers who do not want to design and build their own base.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Workbenches. |

- Landis, Scott (1987). The Workbench Book. Taunton Press. ISBN 0-918804-76-0.

- Schleining, Lon (2004). The Workbench. Taunton Press. ISBN 1-56158-594-7.

- Moxon, Joseph (1703). Mechanick Exercises. London.

- Schwarz, Christopher (February 2001). "$175 Workbench". Popular Woodworking. 120: 64–70.

- Frid, Tage (Fall 1976). "Workbench". Fine Woodworking. 4: 40–45.

- Klausz, Frank (July–August 1985). "A Classic Bench". Fine Woodworking. 53: 62–67.