Taxus baccata

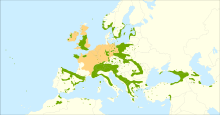

Taxus baccata is a conifer native to western, central and southern Europe, northwest Africa, northern Iran and southwest Asia.[3] It is the tree originally known as yew, though with other related trees becoming known, it may now be known as common yew,[4] English yew,[5] or European yew. Primarily grown as an ornamental, most parts of the plant are poisonous, and consumption of the foliage can result in death.[6][7][8][9]

| Taxus baccata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Taxus baccata (European yew) shoot with mature and immature cones | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Taxaceae |

| Genus: | Taxus |

| Species: | T. baccata |

| Binomial name | |

| Taxus baccata | |

| |

| Natural (native + naturalised) range[2] | |

Taxonomy and naming

The word yew is from Proto-Germanic *īwa-, possibly originally a loanword from Gaulish *ivos, compare Breton ivin, Irish ēo, Welsh ywen, French if (see Eihwaz for a discussion). In German it is known as Eibe. Baccata is Latin for bearing berries. The word yew as it was originally used seems to refer to the color brown.[10] The yew (μίλος) was known to Theophrastus, who noted its preference for mountain coolness and shade, its evergreen character and its slow growth.[11]

Most Romance languages, with the notable exception of French (if), kept a version of the Latin word taxus (Italian tasso, Corsican tassu, Occitan teis, Catalan teix, Gasconic tech, Spanish tejo, Asturian texu, Portuguese teixo, Galician teixo and Romanian tisă) from the same root as toxic. In Slavic languages, the same root is preserved: Polish cis, Russian tis (тис), Serbian-Croatian-Bosnian-Montenegrin tisa/тиса, Slovakian tis, Slovenian tisa. Albanian borrowed it as tis.

In Iran, the tree is known as sorkhdār (Persian: سرخدار, literally "the red tree").

The common yew was one of the many species first described by Linnaeus. It is one of around 30 conifer species in seven genera in the family Taxaceae, which is placed in the order Pinales.

Description

It is a small to medium-sized evergreen tree, growing 10–20 metres (33–66 ft) (exceptionally up to 28 metres (92 ft)) tall, with a trunk up to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) (exceptionally 4 metres (13 ft)) in diameter. The bark is thin, scaly brown, coming off in small flakes aligned with the stem. The leaves are flat, dark green, 1–4 centimetres (0.39–1.57 in) long and 2–3 millimetres (0.079–0.118 in) broad, arranged spirally on the stem, but with the leaf bases twisted to align the leaves in two flat rows either side of the stem, except on erect leading shoots where the spiral arrangement is more obvious. The leaves are poisonous.[3][12]

The seed cones are modified, each cone containing a single seed, which is 4–7 millimetres (0.16–0.28 in) long, and partly surrounded by a fleshy scale which develops into a soft, bright red berry-like structure called an aril. The aril is 8–15 millimetres (0.31–0.59 in) long and wide and open at the end. The arils mature 6 to 9 months after pollination, and with the seed contained, are eaten by thrushes, waxwings and other birds, which disperse the hard seeds undamaged in their droppings. Maturation of the arils is spread over 2 to 3 months, increasing the chances of successful seed dispersal. The seeds themselves are poisonous and bitter, but are opened and eaten by some bird species including hawfinches,[13] greenfinches and great tits.[14] The aril is not poisonous, it is gelatinous and very sweet tasting. The male cones are globose, 3–6 millimetres (0.12–0.24 in) in diameter, and shed their pollen in early spring. The yew is mostly dioecious, but occasional individuals can be variably monoecious, or change sex with time.[3][12][15]

Longevity

Taxus baccata can reach 400 to 600 years of age. Some specimens live longer but the age of yews is often overestimated.[16] Ten yews in Britain are believed to predate the 10th century.[17] The potential age of yews is impossible to determine accurately and is subject to much dispute. There is rarely any wood as old as the entire tree, while the boughs themselves often become hollow with age, making ring counts impossible. Evidence based on growth rates and archaeological work of surrounding structures suggests the oldest yews, such as the Fortingall Yew in Perthshire, Scotland, may be in the range of 2,000 years,[18][19][20] placing them among the oldest plants in Europe. One characteristic contributing to yew's longevity is that it is able to split under the weight of advanced growth without succumbing to disease in the fracture, as do most other trees. Another is its ability to give rise to new epicormic and basal shoots from cut surfaces and low on its trunk, even at an old age.

Significant trees

The Fortingall Yew in Perthshire, Scotland, has the largest recorded trunk girth in Britain and experts estimate it to be 2,000 to 3,000 years old, although it may be a remnant of a post-Roman Christian site and around 1,500 years old.[21] The Llangernyw Yew in Clwyd, Wales, can be found at an early saint site and is about 1,500 years old.[22] Other well known yews include the Ankerwycke Yew, the Balderschwang Yew, the Caesarsboom, the Florence Court Yew, and the Borrowdale Fraternal Four, of which poet William Wordsworth wrote. The Kingley Vale National Nature Reserve in West Sussex has one of Europe's largest yew woodlands.

The oldest specimen in Spain is located in Bermiego, Asturias. It is known as Teixu l'Iglesia in the Asturian language. It stands 15 m (49 ft) tall with a trunk diameter of 6.82 m (22.4 ft) and a crown diameter of 15 m. It was declared a Natural Monument on April 27, 1995 by the Asturian Government and is protected by the Plan of Natural Resources.[23]

A unique forest formed by Taxus baccata and European box (Buxus sempervirens) lies within the city of Sochi, in the Western Caucasus.

The oldest Irish Yew (Taxus baccata 'Fastigiata'), the Florence Court Yew, still stands in the grounds of Florence Court estate in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. The Irish Yew has become ubiquitous in cemeteries across the world and it is believed that all known examples are from cuttings from this tree.[24]

Toxicity

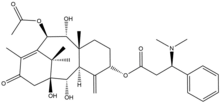

The entire yew bush, except the aril (the red flesh of the berry covering the seed), is poisonous. It is toxic due to a group of chemicals called taxine alkaloids. Their cardiotoxicity is well known and act via calcium and sodium channel antagonism, causing an increase in cytoplasmic calcium currents of the myocardial cells. The seeds contain the highest concentrations of these alkaloids.[25][26] If any leaves or seeds of the plant are ingested, urgent medical advice is recommended as well as observation for at least 6 hours after the point of ingestion.[27][28] The most cardiotoxic taxine is Taxine B followed by Taxine A – Taxine B also happens to be the most common alkaloid in the Taxus species.[29][30][31]

Yew poisonings are relatively common in both domestic and wild animals who consume the plant accidentally,[6][7][8] resulting in "countless fatalities in livestock".[32] The taxine alkaloids are absorbed quickly from the intestine and in high enough quantities can cause death due to cardiac arrest or respiratory failure.[9] Taxines are also absorbed efficiently via the skin and Taxus species should thus be handled with care and preferably with gloves.[33] Taxus baccata leaves contain approximately 5 mg of taxines per 1 g of leaves.[34]

The estimated lethal dose (LDmin) of taxine alkaloids is approximately 3.0mg/kg body weight for humans.[35][36] "The lethal dose for an adult is reported to be 50 g of yew needles. Patients who ingest a lethal dose frequently die due to cardiogenic shock, in spite of resuscitation efforts."[37] There are currently no known antidotes for yew poisoning, but drugs such as atropine have been used to treat the symptoms.[38] Taxine remains in the plant all year, with maximal concentrations appearing during the winter. Dried yew plant material retains its toxicity for several months[39] and even increases its toxicity as the water is removed.[40] Fallen leaves should therefore also be considered toxic. Poisoning usually occurs when leaves of yew trees are eaten, but in at least one case a victim inhaled sawdust from a yew tree.[41]

It is difficult to measure taxine alkaloids and this is a major reason as to why different studies show different results.[42]

Minimum lethal dose, oral LDmin for many different animals were tested:[43]

Chicken 82.5 mg/kg

Cow 10.0 mg/kg

Dog 11.5 mg/kg

Goat 60.0 mg/kg

Horse 1.0–2.0 mg/kg

Pig 3.5 mg/kg

Sheep 12.5 mg/kg

Several studies[44] have found taxine LD50 values under 20 mg/kg in mice and rats. (For symptoms of human toxicity, see Taxine alkaloids.)

Male and monoecious yews in this genus release toxic pollen, which can cause the mild symptoms (). The pollen is also a trigger for asthma. These pollen grains are only 15 microns in size, and can easily pass through most window screens.[45]

Allergenic potential

Yews in this genus are primarily separate-sexed, and males are extremely allergenic, with an OPALS allergy scale rating of 10 out of 10. Completely female yews have an OPALS rating of 1, and are considered "allergy-fighting".[46] Male yews bloom and release abundant amounts of pollen in the spring; completely female yews only trap pollen while producing none.[46]

Uses and traditions

In the ancient Celtic world, the yew tree (*eburos) had extraordinary importance; a passage by Caesar narrates that Cativolcus, chief of the Eburones poisoned himself with yew rather than submit to Rome (Gallic Wars 6: 31). Similarly, Florus notes that when the Cantabrians were under siege by the legate Gaius Furnius in 22 BC, most of them took their lives either by the sword, by fire, or by a poison extracted ex arboribus taxeis, that is, from the yew tree (2: 33, 50–51). In a similar way, Orosius notes that when the Astures were besieged at Mons Medullius, they preferred to die by their own swords or by the yew tree poison rather than surrender (6, 21, 1).

The area of Ydre in the South Swedish highlands is interpreted to mean "place of yews".[47] Two localities in particular, Idhult and Idebo, appear to be further associated with yews.[47]

Religion

The yew is traditionally and regularly found in churchyards in England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and Northern France (particularly Normandy). Some examples can be found in La Haye-de-Routot or La Lande-Patry. It is said up to 40 people could stand inside one of the La-Haye-de-Routot yew trees, and the Le Ménil-Ciboult yew is probably the largest at 13 m diameter.[48] Yews may grow to become exceptionally large (over 5 m diameter) and may live to be over 2,000 years old. Sometimes monks planted yews in the middle of their cloister, as at Muckross Abbey (Ireland) or abbaye de Jumièges (Normandy). Some ancient yew trees are located at St. Mary the Virgin Church, Overton-on-Dee in Wales.

In Asturian tradition and culture, the yew tree was considered to be linked with the land, people, ancestors and ancient religion. It was tradition on All Saints' Day to bring a branch of a yew tree to the tombs of those who had died recently so they would be guided in their return to the Land of Shadows. The yew tree has been found near chapels, churches and cemeteries since ancient times as a symbol of the transcendence of death. They are often found in the main squares of villages where people celebrated the open councils that served as a way of general assembly to rule village affairs.[49]

It has been suggested that the sacred tree at the Temple at Uppsala was an ancient yew tree.[50][51] The Christian church commonly found it expedient to take over existing pre-Christian sacred sites for churches. It has also been suggested that yews were planted at religious sites as their long life was suggestive of eternity, or because, being toxic when ingested, they were seen as trees of death.[52] Another suggested explanation is that yews were planted to discourage farmers and drovers from letting animals wander onto the burial grounds, the poisonous foliage being the disincentive. A further possible reason is that fronds and branches of yew were often used as a substitute for palms on Palm Sunday.[53][54][55]

Some yew trees were actually native to the sites before the churches were built. King Edward I of England ordered yew trees to be planted in churchyards to offer some protection to the buildings. Yews are poisonous so by planting them in the churchyards cattle that were not allowed to graze on hallowed ground were safe from eating yew. Yew branches touching the ground take root and sprout again; this became a symbol of death, rebirth and therefore immortality.[55]

In interpretations of Norse cosmology, the tree Yggdrasil has traditionally been interpreted as a giant ash tree. Some scholars now believe errors were made in past interpretations of the ancient writings, and that the tree is most likely a European yew (Taxus baccata).[56]

In the Crann Ogham—the variation on the ancient Irish Ogham alphabet which consists of a list of trees—yew is the last in the main list of 20 trees, primarily symbolizing death. There are stories of people who have committed suicide by ingesting the foliage. As the ancient Celts also believed in the transmigration of the soul, there is in some cases a secondary meaning of the eternal soul that survives death to be reborn in a new form.[57]

Medical

Certain compounds found in the bark of yew trees were discovered by Wall and Wani in 1967 to have efficacy as anti-cancer agents. The precursors of the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel (taxol) were later shown to be synthesized easily from extracts of the leaves of European yew,[58] which is a much more renewable source than the bark of the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia) from which they were initially isolated. This ended a point of conflict in the early 1990s; many environmentalists, including Al Gore, had opposed the destructive harvesting of Pacific yew for paclitaxel cancer treatments. Docetaxel can then be obtained by semi-synthetic conversion from the precursors.

Woodworking and longbows

Wood from the yew is classified as a closed-pore softwood, similar to cedar and pine. Easy to work, yew is among the hardest of the softwoods; yet it possesses a remarkable elasticity, making it ideal for products that require springiness, such as bows.[59] Due to all parts of the yew and its volatile oils being poisonous and cardiotoxic,[3][12][60] a mask should be worn if one comes in contact with sawdust from the wood.[61]

One of the world's oldest surviving wooden artifacts is a Clactonian yew[62] spear head, found in 1911 at Clacton-on-Sea, in Essex, UK. Known as the Clacton Spear, it is estimated to be over 400,000 years old.[63][64]

Yew is also associated with Wales and England because of the longbow, an early weapon of war developed in northern Europe, and as the English longbow the basis for a medieval tactical system. The oldest surviving yew longbow was found at Rotten Bottom in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. It has been given a calibrated radiocarbon date of 4040 BC to 3640 BC and is on display in the National Museum of Scotland. Yew is the wood of choice for longbow making; the heartwood is always on the inside of the bow with the sapwood on the outside. This makes most efficient use of their properties as heartwood is best in compression whilst sapwood is superior in tension. However, much yew is knotty and twisted, and therefore unsuitable for bowmaking; most trunks do not give good staves and even in a good trunk much wood has to be discarded.

There was a tradition of planting yew trees in churchyards throughout Britain and Ireland, among other reasons, as a resource for bows. "Ardchattan Priory whose yew trees, according to other accounts, were inspected by Robert the Bruce and cut to make at least some of the longbows used at the Battle of Bannockburn."[65]

The trade of yew wood to England for longbows was so robust that it depleted the stocks of good-quality, mature yew over a vast area. The first documented import of yew bowstaves to England was in 1294. In 1350 there was a serious shortage, and Henry IV of England ordered his royal bowyer to enter private land and cut yew and other woods. In 1423 the Polish king commanded protection of yews in order to cut exports, facing nearly complete destruction of local yew stock.[66] In 1470 compulsory archery practice was renewed, and hazel, ash, and laburnum were specifically allowed for practice bows. Supplies still proved insufficient, until by the Statute of Westminster in 1472, every ship coming to an English port had to bring four bowstaves for every tun.[67] Richard III of England increased this to ten for every tun. This stimulated a vast network of extraction and supply, which formed part of royal monopolies in southern Germany and Austria. In 1483, the price of bowstaves rose from two to eight pounds per hundred, and in 1510 the Venetians would only sell a hundred for sixteen pounds. In 1507 the Holy Roman Emperor asked the Duke of Bavaria to stop cutting yew, but the trade was profitable, and in 1532 the royal monopoly was granted for the usual quantity "if there are that many." In 1562, the Bavarian government sent a long plea to the Holy Roman Emperor asking him to stop the cutting of yew, and outlining the damage done to the forests by its selective extraction, which broke the canopy and allowed wind to destroy neighbouring trees. In 1568, despite a request from Saxony, no royal monopoly was granted because there was no yew to cut, and the next year Bavaria and Austria similarly failed to produce enough yew to justify a royal monopoly. Forestry records in this area in the 17th century do not mention yew, and it seems that no mature trees were to be had. The English tried to obtain supplies from the Baltic, but at this period bows were being replaced by guns in any case.[68]

Horticulture

Today European yew is widely used in landscaping and ornamental horticulture. Due to its dense, dark green, mature foliage, and its tolerance of even very severe pruning, it is used especially for formal hedges and topiary. Its relatively slow growth rate means that in such situations it needs to be clipped only once per year (in late summer).

Well over 200 cultivars of T. baccata have been named. The most popular of these are the Irish yew (T. baccata 'Fastigiata'), a fastigiate cultivar of the European yew selected from two trees found growing in Ireland, and the several cultivars with yellow leaves, collectively known as "golden yew".[12][15] In some locations, e.g. when hemmed in by buildings or other trees, an Irish yew can reach 20 feet in height without exceeding 2 feet in diameter at its thickest point, although with age many Irish yews assume a fat cigar shape rather than being truly columnar.

The following cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:-[69]

European yew will tolerate growing in a wide range of soils and situations, including shallow chalk soils and shade,[77] although in deep shade its foliage may be less dense. However it cannot tolerate waterlogging, and in poorly-draining situations is liable to succumb to the root-rotting pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi.

In Europe, Taxus baccata grows naturally north to Molde in southern Norway, but it is used in gardens further north. It is also popular as a bonsai in many parts of Europe and makes a handsome small- to large-sized bonsai.[78]

Privies

In England, yew has historically been sometimes associated with privies (outside toilets), possibly because the smell of the plant keeps insects away.[79]

Musical instruments

The late Robert Lundberg, a noted luthier who performed extensive research on historical lute-making methodology, states in his 2002 book Historical Lute Construction that yew was historically a prized wood for lute construction. European legislation establishing use limits and requirements for yew limited supplies available to luthiers, but it was apparently as prized among medieval, renaissance, and baroque lute builders as Brazilian rosewood is among contemporary guitar-makers for its quality of sound and beauty.

Conservation

Clippings from ancient specimens in the UK, including the Fortingall Yew, were taken to the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh to form a mile-long hedge. The purpose of this "Yew Conservation Hedge Project" is to maintain the DNA of Taxus baccata. The species is threatened by felling, partly due to rising demand from pharmaceutical companies, and disease.[80]

Another conservation programme was run in Catalonia in the early 2010s, by the Forest Sciences Centre of Catalonia (CTFC), in order to protect genetically endemic yew populations, and preserve them from overgrazing and forest fires.[81] In the framework of this programme, the 4th International Yew Conference was organised in the Poblet Monastery in 2014, which proceedings are available.

There has also been a conservation programme in northern Portugal and Northern Spain (Cantabrian Range).[82]

See also

References

- Farjon, A. (2013). "Taxus baccata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T42546A117052436. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42546A2986660.en.{{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |page= mismatch (help)

- Benham, S. E., Houston Durrant, T., Caudullo, G., de Rigo, D., 2016. Taxus baccata in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats. In: San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A. (Eds.), European Atlas of Forest Tree Species. Publ. Off. EU, Luxembourg, pp. e015921+

- Rushforth, K. (1999). Trees of Britain and Europe. Collins ISBN 0-00-220013-9.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Taxus baccata". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "Taxus baccata". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "JAPANESE YEW PLANT POISONING – USA: (IDAHO) PRONGHORN ANTELOPE". ProMED-mail. 24 January 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- "PLANT POISONING, CERVID – USA: (ALASKA) ORNAMENTAL TREE, MOOSE". ProMED-mail. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- Tiwary, Asheesh K.; Puschner, Birgit; Kinde, Hailu; Tor, Elizabeth R. (May 2005). "Diagnosis of Taxus (yew) poisoning in a horse". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 17 (3): 252–255>. doi:10.1177/104063870501700307. ISSN 1040-6387. PMID 15945382.

- Fuller, Thomas C.; McClintock, Elizabeth M. (1986). Poisonous plants of California. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520055683. OCLC 13009854.

- Douglas Simms. "A Celto-Germanic Etymology for Flora and Fauna which will Boar Yew". Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants, iii.10.2; iv.1.3, etc.

- Mitchell, A. F. (1972). Conifers in the British Isles. Forestry Commission Booklet 33.

- "The Hawfinch". Wbrc.org.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- Snow, David; Snow, Barbara (2010). Birds and Berries. London: A & C Black. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9781408138229.

- Dallimore, W., & Jackson, A. B. (1966). A Handbook of Coniferae and Ginkgoaceae 4th ed. Arnold.

- Mayer, Hannes (1992). Waldbau auf soziologisch-ökologischer Grundlage [Silviculture on socio-ecological basis] (in German) (4th ed.). Fischer. p. 97. ISBN 3-437-30684-7.

- Bevan-Jones, Robert (2004). The ancient yew: a history of Taxus baccata. Bollington: Windgather Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-9545575-3-0.

- Harte, J. (1996). How old is that old yew? At the Edge 4: 1–9.online.

- Kinmonth, F. (2006). Ageing the yew – no core, no curve? International Dendrology Society Yearbook 2005: 41–46.

- Lewington, A., & Parker, E. (1999). Ancient Trees: Trees that Live for a Thousand Years. London: Collins & Brown Ltd. ISBN 1-85585-704-9

- Bevan-Jones, Robert (2004). The ancient yew: a history of Taxus baccata. Bollington: Windgather Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-9545575-3-0.

- Bevan-Jones, Robert (2004). The ancient yew: a history of Taxus baccata. Bollington: Windgather Press. p. 49. ISBN 0-9545575-3-0.

- "Monumentos Naturales" (in Spanish). Gobierno del Principado de Asturias. Retrieved 14 March 2013. Contains Word document "Monumento Natural Teixu de Bermiego".

- "The original Irish Yew Tree at Florence Court". National Trust. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- Garland, Tam; Barr, A. Catherine (1998). Toxic plants and other natural toxicants. International Symposium on Poisonous Plants (5th : 1997 : Texas). Wallingford, England: CAB International. ISBN 0851992633. OCLC 39013798.

- Alloatti, G.; Penna, C.; Levi, R.C.; Gallo, M.P.; Appendino, G.; Fenoglio, I. (1996). "Effects of yew alkaloids and related compounds on guinea-pig isolated perfused heart and papillary muscle". Life Sciences. 58 (10): 845–854. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(96)00018-5. ISSN 0024-3205. PMID 8602118.

- "TOXBASE - National Poisons Information Service".

- "Plants for a Future Taxus baccata". Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- Alloatti, G.; Penna, C.; Levi, R. C.; Gallo, M. P.; Appendino, G.; Fenoglio, I. (1996). "Effects of yew alkaloids and related compounds on guinea-pig isolated perfused heart and papillary muscle". Life Sciences. 58 (10): 845–854. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(96)00018-5. ISSN 0024-3205. PMID 8602118.

- Smythies, J.R.; Benington, F.; Morin, R.D.; Al-Zahid, G.; Schoepfle, G. (1975). "The action of the alkaloids from yew (Taxus baccata) on the action potential in the Xenopus medullated axon". Experientia. 31 (3): 337–338. doi:10.1007/bf01922572. PMID 1116544.

- Wilson, Christina R.; Sauer, John-Michael; Hooser, Stephen B. (2001). "Taxines: a review of the mechanism and toxicity of yew (Taxus spp.) alkaloids". Toxicon. 39 (2–3): 175–185. doi:10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00146-x. ISSN 0041-0101. PMID 10978734.

- Krenzelok, EP (1998). "Is the yew really poisonous to you?". Journal of Toxicology. PMID 9656977.

- Mitchell, A. F. (1972). Conifers in the British Isles. Forestry Commission Booklet 33.

- Smythies, J.R.; Benington, F.; Morin, R.D.; Al-Zahid, G.; Schoepfle, G. (1975). "The action of the alkaloids from yew (Taxus baccata) on the action potential in the Xenopus medullated axon". Experientia. 31 (3): 337–338. doi:10.1007/bf01922572. PMID 1116544.

- Watt, J.M.; Breyer-Brandwijk, M.G. (1962). Taxaceae. In The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa. Edinburgh, UK: Livingston. pp. 1019–1022.

- Kobusiak-Prokopowicz, Małgorzata (2016). "A suicide attempt by intoxication with Taxus baccata leaves and ultra-fast liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry, analysis of patient serum and different plant samples: case report". BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 17 (1): 41. doi:10.1186/s40360-016-0078-5. PMC 5006531. PMID 27577698.

- Piskač, Ondřej (June 2015). "Cardiotoxicity of yew". Cor et Vasa. 57 (3): 234–238. doi:10.1016/j.crvasa.2014.11.003. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Wilson, Christina R.; Hooser, Stephen B. (2018). Veterinary Toxicology. Elsevier. pp. 947–954. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-811410-0.00066-0. ISBN 9780128114100.

- "Guide to Poisonous Plants – College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences – Colorado State University". Colorado State University. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- "Yew". Provet. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- José Luis Hernández Hernández; Fernando Quijano Terán; Jesús González Macías (2010). "Intoxicación por tejo". Medicina Clínica. 135 (12): 575–576. doi:10.1016/j.medcli.2009.06.036. PMID 19819481.

- Clarke, E.G.C.; Clarke, M.L. (1988). "Poisonous plants, Taxaceae". In Humphreys, David John (ed.). Veterinary Toxicology (3rd ed.). London: Baillière, Tindall & Cassell. pp. 276–277. ISBN 9780702012495.

- Clarke, E.G.C.; Clarke, M.L. (1988). "Poisonous plants, Taxaceae". In Humphreys, David John (ed.). Veterinary Toxicology (3rd ed.). London: Baillière, Tindall & Cassell. pp. 276–277. ISBN 9780702012495.

- TAXINE – National Library of Medicine HSDB Database, section "Animal Toxicity Studies"

- "Pollen images in size order". www.saps.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- Ogren, Thomas (2015). The Allergy-Fighting Garden. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. p. 205. ISBN 9781607744917.

- Wahlberg, Mats, ed. (2003). Svensk ortnamnslexikon (PDF) (in Swedish). Uppsala: Språk- och folkminnesinstitutet. p. 375. ISBN 91-7229-020-X. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- List of world largest trees

- Abella Mina, I. Árboles De Junta Y Concejo. Las Raíces De La Comunidad. Libros del Jata, First Edition, 2016. ISBN 9788416443024

- Ohlmarks, Å. (1994). Fornnordiskt lexikon. p 372.

- Hellquist, O. (1922). Svensk etymologisk ordbok. p 266

- Andrews, W.(ed.)(1897) 'Antiquities and Curiosities of the Church, William Andrews & Co., London 1897; pp. 256-278: 'Amongst the ancients the yew, like the cypress, was regarded as the emblem of death... As, to the early Christian, death was the harbinger of life; he could not agree with his classic forefathers in employing the yew or the cyprus, "as an emblem of their dying for ever." It was the very antithesis of this, and as an emblem of immortality, and to show his belief in the life beyond the grave, that led to his cultivation of the yew in all the burying grounds of those who died in the new faith, and this must be regarded as the primary idea of its presence there... Evelyn’s opinion is more decisive: —"that we find it so universally planted in our churchyards, was doubtless, from its being thought a symbol of immortality, the tree being so lasting and always green."'

- Andrews, W.(ed.)(1897) 'The majority of authorities agree that in England; branches of yew were generally employed; and some express the opinion, that the principal object of the tree being planted in churchyards, was to supply branches of it for this purpose.'

- "Palm Sunday: All About Palm Sunday of the Lord's Passion". Churchyear.net. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- Dún Laoghaire Parks

- Bevan-Jones, Robert (2017), The Ancient Yew: A History of Taxus baccata (3rd ed.), Windgather Press, pp. 150–

- Andrews, W.(ed.)(1897) 'Antiquities and Curiosities of the Church, William Andrews & Co., London 1897; pp. 256-278: 'Amongst the ancients the yew, like the cypress, was regarded as the emblem of death.

- National Non-Food Crops Centre, "Yew" Archived 2009-03-26 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2009-04-23.

- The Wood Database: European Yew

- "Taxus baccata, yew - THE POISON GARDEN website". Thepoisongarden.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- "How poisonous is the yew?". Ancient-yew.org. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- "THE CLACTON SPEAR TIP".

- White, T.S.; Boreham, S.; Bridgland, D. R.; Gdaniec, K.; White, M. J. (2008). "The Lower and Middle Palaeolithic of Cambridgeshire" (PDF). English Heritage Project. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Laing, Lloyd; Laing, Jennifer (1980). The Origins of Britain. Book Club Associates. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0710004311.

- Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, Volume 62. 2004. Page 35.

- Romuald Sztyk. Obrót nieruchomościami w świetle prawa o ochronie środowiska. "Rejent - Miesięcznik Notariatu Polskiego". 10 (150), October 2003

- "...because that our sovereign lord the King, by a petition delivered to him in the said parliament, by the commons of the same, hath perceived That the great scarcity of bowstaves is now in this realm, and the bowstaves that be in this realm be sold as an excessive price...", Statutes at Large

- Yew: A History. Hageneder F. Sutton Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7509-4597-4.

- "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 100. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Taxus baccata 'Fastigiata'". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Taxus baccata 'Fastigiata Aureomarginata'". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "RHS Plantfinder - Taxus baccata 'Icicle'". Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Taxus baccata 'Repandens'". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Taxus baccata 'Repens Aurea'". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Taxus baccata 'Semperaurea'". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Taxus baccata 'Standishii'". Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- Hillier Nurseries, "The Hillier Manual Of Trees And Shrubs", David & Charles, 1998, p863

- D'Cruz, Mark. "Ma-Ke Bonsai Care Guide for Taxus baccata". Ma-Ke Bonsai. Retrieved 2011-11-19.

- "Cerne Privies". Barnwells House and Garden. Retrieved 2016-12-26.

- "Ancient yew DNA preserved in hedge project". United Press International. 7 November 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Casals, Pere; Camprodon, Jordi; Caritat, Antonia; Rios, Ana; Guixe, David; Garcia-Marti, X; Martin-Alarcon, Santiago; Coll, Lluis (2015). "Forest structure of Mediterranean yew (Taxus baccata L.) populations and neighbor effects on juvenile yew performance in the NE Iberian Peninsula" (PDF). Forest Systems. 24 (3): e042. doi:10.5424/fs/2015243-07469.

- "LIFE Baccata Project". LIFE Baccata EU project.

Further reading

- Chetan, A. and Brueton, D. (1994) The Sacred Yew, London: Arkana, ISBN 0-14-019476-2

- Hartzell, H. (1991) The yew tree: a thousand whispers: biography of a species, Eugene: Hulogosi, ISBN 0-938493-14-0

- Simón, F. M. (2005) Religion and Religious Practices of the Ancient Celts of the Iberian Peninsula, e-Keltoi, v. 6, p. 287-345, ISSN 1540-4889 online

- Casals, Pere; Camprodon, Jordi; Caritat, Antonia; Rios, Ana; Guixe, David; Garcia-Marti, X; Martin-Alarcon, Santiago; Coll, Lluis (2015). "Forest structure of Mediterranean yew (Taxus baccata L.) populations and neighbor effects on juvenile yew performance in the NE Iberian Peninsula" (PDF). Forest Systems. 24 (3): e042. doi:10.5424/fs/2015243-07469.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Yew |

- Monumentaltrees.com: Images and location details of ancient yews

- Life+ TAXUS.cat: Taxus conservation programme in Catalonia

- Forest Sciences Centre of Catalonia (CTFC)—Biology Conservation Department

- Taxus baccata—distribution map, genetic conservation units, and related resources from the European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN)