Turkmenistan–Uzbekistan border

The Turkmenistan–Uzbekistan border is the border between the countries of the Republic of Turkmenistan and the Republic of Uzbekistan. At 1,793 km (1,114m), it is Turkmenistan's longest border and Uzbekistan's second longest (behind Uzbekistan's border with Kazakhstan). The border runs from the tripoint with Kazakhstan to the tripoint with Afghanistan.[1]

| Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan Border | |

|---|---|

Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan border crossing in Farap (Turkmen side). | |

| Characteristics | |

| Entities | |

| Length | 1,793 km (1,114 mi) |

| History | |

| Established | May 13, 1925 |

| Current shape | September 27, 1991 |

The Turkmenistan–Uzbekistan border was first established in 1925, when both countries were part of the Soviet Union as the Turkmen SSR and the Uzbek SSR respectively. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan became independent countries, making the Turkmenistan–Uzbekistan border an international border. A joint treaty was signed between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan in 2000, recognizing the post-independence border as the official border between the two countries, ending a decade of disputes and establishing the border's current shape. A border fence was constructed afterward.

Description

The border starts in the west at the tripoint with Kazakhstan. It follows a roughly straight line eastwards before turning sharply north and then north-eastwards, passing through Sarygamysh Lake which straddles the border; also in this section is a long protrusion of Uzbek territory into Turkmenistan. The border then turns south-eastwards in the vicinity of Shumanay, following a somewhat convoluted course until it reaches the Amu Darya river in the vicinity of Pitnak and Gazojak; it then follows the river down to the 40th parallel north. The border then follows a series of straight lines segments south-east through the Karakum desert, before turning southwards through Köýtendag Range down to the tripoint with Afghanistan on the Amu Darya. Much of the border is traversed by a major railway which crosses the border three times, a legacy of the Soviet era where infrastructure was built without regard to what were then internal boundaries.

History

Russia had conquered Central Asia in the 19th century by annexing the formerly independent Khanates of Kokand and Khiva and the Emirate of Bukhara. After the Communists took power in 1917 and created the Soviet Union it was decided to divide Central Asia into ethnically-based republics in a process known as National Territorial Delimitation (or NTD). This was in line with Communist theory that nationalism was a necessary step on the path towards an eventually communist society, and Joseph Stalin’s definition of a nation as being “a historically constituted, stable community of people, formed on the basis of a common language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a common culture”.

The NTD is commonly portrayed as being nothing more than a cynical exercise in divide and rule, a deliberately Machiavellian attempt by Stalin to maintain Soviet hegemony over the region by artificially dividing its inhabitants into separate nations and with borders deliberately drawn so as to leave minorities within each state.[2] Though indeed the Soviets were concerned at the possible threat of pan-Turkic nationalism,[3] as expressed for example with the Basmachi movement of the 1920s, closer analysis informed by the primary sources paints a much more nuanced picture than is commonly presented.[4][5][6]

The Soviets aimed to create ethnically homogeneous republics, however many areas were ethnically-mixed (e.g. the Ferghana Valley) and it often proved difficult to assign a ‘correct’ ethnic label to some peoples (e.g. the mixed Tajik-Uzbek Sart, or the various Turkmen/Uzbek tribes along the Amu Darya).[7][8] Local national elites strongly argued (and in many cases overstated) their case and the Soviets were often forced to adjudicate between them, further hindered by a lack of expert knowledge and the paucity of accurate or up-to-date ethnographic data on the region.[7][9] Furthermore NTD also aimed to create ‘viable’ entities, with economic, geographical, agricultural and infrastructural matters also to be taken into account and frequently trumping those of ethnicity.[10][11] The attempt to balance these contradictory aims within an overall nationalist framework proved exceedingly difficult and often impossible, resulting in the drawing of often tortuously convoluted borders, multiple enclaves and the unavoidable creation of large minorities who ended up living in the ‘wrong’ republic. Additionally the Soviets never intended for these borders to become international frontiers as they are today.

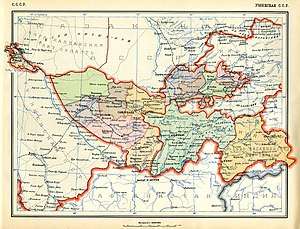

NTD of the area along ethnic lines had been proposed as early as 1920.[12][13] At this time Central Asia consisted of two Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics (ASSRs) within the Russian SFSR: the Turkestan ASSR, created in April 1918 and covering large parts of what are now southern Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, as well as Turkmenistan), and the Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Kirghiz ASSR, Kirgizistan ASSR on the map), which was created on 26 August 1920 in the territory roughly coinciding with the northern part of today's Kazakhstan (at this time Kazakhs were referred to as ‘Kyrgyz’ and what are now the Kyrgyz were deemed a sub-group of the Kazakhs and referred to as ‘Kara-Kyrgyz’ i.e. mountain-dwelling ‘black-Kyrgyz’). There were also the two separate successor ‘republics’ of the Emirate of Bukhara and the Khanate of Khiva, which were transformed into the Bukhara and Khorezm People's Soviet Republics following the takeover by the Red Army in 1920.[14]

On 25 February 1924 the Politburo and Central Committee of the Soviet Union announced that it would proceed with NTD in Central Asia.[15][16] The process was to be overseen by a Special Committee of the Central Asian Bureau, with three sub-committees for each of what were deemed to be the main nationalities of the region (Kazakhs, Turkmen and Uzbeks), with work then exceedingly rapidly.[17][18][19][20][21] There were initial plans to possibly keep the Khorezm and Bukhara PSRs, however it was eventually decided to partition them in April 1924, over the often vocal opposition of their Communist Parties (the Khorezm Communists in particular were reluctant to destroy their PSR and had to be strong-armed into voting for their own dissolution in July of that year).[22]

The creation of Turkmenistan was hampered by a weak sense of Turkmen nationality, many of whom identified with their tribe first before that of the wider Turkmen identity. However, the Turkmen Communist elite pushed hard for the creation of a united Turkmen SSR, aided by the fact that the region was relatively homogeneous.[23] However ethnic identities along the Amu Darya were complex and it was often difficult to judge which groups were ‘Turkmen’ and which ‘Uzbek’ (e.g. the Salur, Bayad, Kurama, Ersarï, Khïdar-Alï etc.).[24] Turkmen Communists pushed for a ‘maximalist’ Turkmenistan, opting to include all ambiguous groups as Turkmen.[25] Their efforts gained them the cities of Farap and Chardzhou (modern Türkmenabat), both of which were also claimed by the Uzbeks.[26][9] The Uzbeks were particular outraged when the city of Tashauz (modern Daşoguz) was given to Turkmenistan despite it having a predominantly Uzbek population, as the Soviet authorities deemed the Turkmen SSR to be lacking in cities, deemed essential for industrial development.[27][28][29]

The Turkmen SSR and the Uzbek SSR were officially created in 1924. Uzbekistan at this time did not include the then much larger Karakalpakstan ASSR, hence the border originally consisted of two separate non-contiguous sections divided by the Kazak ASSR; in 1936 the Karakalpak ASSR was transferred to the Uzbek SSR and the border took its current shape.

The boundary became an international frontier in 1991 following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the independence of its constituent republics. After some tensions in the 1990s Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan agreed to respect the traditional inter-republic border, with a joint treaty to this effect being signed in 2000 by Presidents Saparmurat Niyazov and Islom Karimov.[30] On March 30, 2001 Turkmenistan's President Saparmurat Niyazov ordered his government to finish construction of the 1,700-kilometer border fence along Turkmenistan's border with Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan by the end of the year to prevent smuggling and illegal migration:[31]

And here we have our border issues too. We have borders on this and on that side as with the Kazakhs. We have already started to built [sic] wire fences on the borders. You must provide all necessary support for this. Let there be crossing-points in specified areas. We are not doing this to separate ourselves from Uzbekistan or Kazakhstan but are doing so to maintain order on the border, to protect ourselves from violators and dishonest people and to prevent our goods from being smuggled. There are special crossing-points to prevent such things, and to ensure permitted and regulated border crossing on a legal basis. We have this in Koytendag [eastern Turkmenistan] as well as in other border districts of Lebap Region. Yesterday we started this [construction of wire fences] in Lebap, and earlier in Dashoguz. You must finish putting up this fence, all 1,700 km of it, by the end of this year. We need this to avoid any future dispute between us and to prevent any violators from entering. As we all are sovereign states, we cannot keep the borders open any more, for there could be trespassers from third countries.[32][33]

Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan had serious "issues" regarding their mutual border until May 2004 when the Turkmen Foreign Ministry released a statement on May 31, 2004 saying disputes had been resolved.[34][35] Relations appear to have further improved in recent years, with full demarcation of the border ongoing.[36]

Border crossings

Settlements near the border

Turkmenistan

- Konye-Urgench

- Imeni Gorkogo

- Takhiadash

- Daşoguz

- Gazojak

- Dargan Ata

- Turkmenabat

- Farap

Uzbekistan

References

- CIA World Factbook - Uzbekistan, 23 September 2018

- The charge is so common as to have become almost the conventional wisdom within mainstream journalistic coverage of Central Asia, with Stalin himself often the one drawing the borders, see for example Stourton, E. in The Guardian, 2010 Kyrgyzstan: Stalin's deadly legacy https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/jun/20/kyrgyzstan-stalins-deadly-legacy; Zeihan, P. for Stratfor, 2010 The Kyrgyzstan Crisis and the Russian Dilemma https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/kyrgyzstan-crisis-and-russian-dilemma; The Economist, 2010 Kyrgyzstan - Stalin's Harvest https://www.economist.com/briefing/2010/06/17/stalins-harvest?story_id=16377083; Pillalamarri, Akhilesh in the Diplomat, 2016, The Tajik Tragedy of Uzbekistan https://thediplomat.com/2016/09/the-tajik-tragedy-of-uzbekistan/; Rashid, A in the New York Review of Books, 2010, Tajikistan - the Next Jihadi Stronghold? https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2010/11/29/tajikistan-next-jihadi-stronghold; Schreck, C. in The National, 2010, Stalin at core of Kyrgyzstan carnage, https://www.thenational.ae/world/asia/stalin-at-core-of-kyrgyzstan-carnage-1.548241

- Bergne, Paul (2007) The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic, IB Taurus & Co Ltd, pg. 39-40

- Haugen, Arne (2003) The Establishment of National Republics in Central Asia, Palgrave Macmillan, pgs. 24-5, 182-3

- Khalid, Adeeb (2015) Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR, Cornell University Press, pg. 13

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pg. 46

- Bergne, Paul (2007) The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic, IB Taurus & Co Ltd, pg. 44-5

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pg. 47

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pg. 53

- Bergne, Paul (2007) The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic, IB Taurus & Co Ltd, pg. 43-4

- Starr, S. Frederick (ed.) (2011) Ferghana Valley – the Heart of Central Asia Routledge, pg. 112

- Bergne, Paul (2007) The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic, IB Taurus & Co Ltd, pg. 40-1

- Starr, S. Frederick (ed.) (2011) Ferghana Valley – the Heart of Central Asia Routledge, pg. 105

- Bergne, Paul (2007) The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic, IB Taurus & Co Ltd, pg. 39

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pg. 55

- Bergne, Paul (2007) The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic, IB Taurus & Co Ltd, pg. 42

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pg. 54

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pgs. 52-3

- Bergne, Paul (2007) The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic, IB Taurus & Co Ltd, pg. 92

- Starr, S. Frederick (ed.) (2011) Ferghana Valley – the Heart of Central Asia Routledge, pg. 106

- Khalid, Adeeb (2015) Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR, Cornell University Press, pg. 271-2

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pgs. 56-8

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pgs. 49-51

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pgs. 60-1

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Names ation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pgs. 62

- Haugen, Arne (2003) The Establishment of National Republics in Central Asia, Palgrave Macmillan, pg. 139, 187

- Haugen, Arne (2003) The Establishment of National Republics in Central Asia, Palgrave Macmillan, pg. 185-6

- Khalid, Adeeb (2015) Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR, Cornell University Press, pg. 276

- Edgar, Adrienne Lynn (2004) Tribal Nation: The Making Of Soviet Turkmenistan, Princeton University Press, pgs. 63

- Trofimov, Dmitriy (2002), Ethnic/Territorial and Border Problems in Central Asia, retrieved 28 October 2018

- Rein, Abraham (April 2, 2001). "Turkmenistan's Niyazov wants fence along the border". Eurasianet. Archived from the original on 2007-07-06. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- "TURKMENISTAN-UZBEKISTAN: Cross border movement remains problematic". Integrated Regional Information Networks. June 6, 2005. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- Burke, Justin (April 2, 2001). "Niiyazov Calls For Fortifying Borders". Eurasianet. Archived from the original on 2007-07-06. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- Dates Related to Elections, Officials, and Policy 2004. RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty Archived May 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- International Crisis Group (4 April 2002), CENTRAL ASIA - BORDER DISPUTES AND CONFLICT POTENTIAL (PDF), retrieved 28 October 2018

- European Institute for Asian Studies (2018), Note of Comment on Relations between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan ahead of the Visit By President Berdimuhamedov to Tashkent, retrieved 28 October 2018

- Caravanistan - Uzbekistan border crossings, retrieved 7 October 2018