Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (Arabic: دلتا النيل Delta an-Nīl or simply الدلتا ad-Delta) is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the east, it covers 240 km (150 mi) of Mediterranean coastline and is a rich agricultural region. From north to south the delta is approximately 160 km (99 mi) in length. The Delta begins slightly down-river from Cairo.[1]

Geography

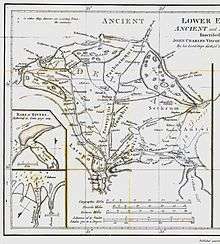

From north to south, the delta is approximately 160 km (99 mi) in length. From west to east, it covers some 240 km (150 mi) of coastline. The delta is sometimes divided into sections, with the Nile dividing into two main distributaries, the Damietta and the Rosetta,[2] flowing into the Mediterranean at port cities with the same name. In the past, the delta had several distributaries, but these have been lost due to flood control, silting and changing relief. One such defunct distributary is Wadi Tumilat.

The Suez Canal is east of the delta and enters the coastal Lake Manzala in the north-east of the delta. To the north-west are three other coastal lakes or lagoons: Lake Burullus, Lake Idku and Lake Mariout.

The Nile is considered to be an "arcuate" delta (arc-shaped), as it resembles a triangle or flower when seen from above. Some scholars such as Aristotle have written that the delta was constructed for agricultural purposes due to the drying of the region of Egypt. Although such an engineering feat would be considered equivalent to a wonder of the ancient world, there is insufficient evidence to determine conclusively whether the delta is man-made or was formed naturally.[3]

In modern day, the outer edges of the delta are eroding, and some coastal lagoons have seen increasing salinity levels as their connection to the Mediterranean Sea increases. Since the delta no longer receives an annual supply of nutrients and sediments from upstream due to the construction of the Aswan Dam, the soils of the floodplains have become poorer, and large amounts of fertilizers are now used. Topsoil in the delta can be as much as 21 m (70 ft) in depth.

History

People have lived in the Nile Delta region for thousands of years, and it has been intensively farmed for at least the last five thousand years. The delta was a major constituent of Lower Egypt, and there are many archaeological sites in and around the delta.[4] Artifacts belonging to ancient sites have been found on the delta's coast. The Rosetta Stone was found in the delta in 1799 in the port city of Rosetta (an anglicized version of the name Rashid). In July 2019 a small Greek temple, ancient granite columns, treasure-carrying ships, and bronze coins from the reign of Ptolemy II, dating back to the third and fourth centuries BC, were found at the sunken city of Heracleion, colloquially known as Egypt's Atlantis. The investigations were conducted by Egyptian and European divers led by the underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio. They also uncovered a devastated historic temple (the city's main temple) underwater off Egypt's north coast.[5][6][7][8][9][10]

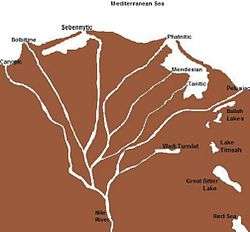

Ancient branches of the Nile

Records from ancient times (such as by Pliny the Elder) show that the delta had seven distributaries or branches, (from east to west):[2]

- the Pelusiac,

- the Tanitic,

- the Mendesian,

- the Phatnitic (or Phatmetic),[11]

- the Sebennytic,

- the Bolbitine, and

- the Canopic (also called the Herakleotic[12] and the Agathodaemon[13])

There are now only two main branches, due to flood control, silting and changing relief: the Damietta (corresponding to the Phatnitic) to the east, and the Rosetta (corresponding to the Bolbitine)[14] in the western part of the Delta. The Delta used to flood annually, but this ended with the construction of the Aswan Dam.

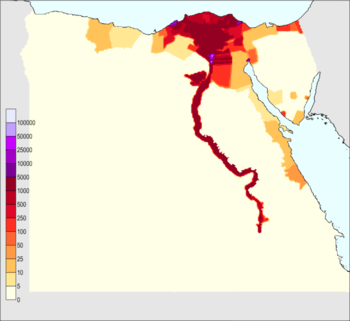

Population

About 39 million people live in the Delta region. Outside of major cities, population density in the delta averages 1,000/km2 (2,600/sq mi) or more. Alexandria is the largest city in the delta with an estimated population of more than 4.5 million. Other large cities in the delta include Shubra El Kheima, Port Said, El Mahalla El Kubra, Mansura, Tanta, and Zagazig.[15]

Wildlife

During autumn, parts of the Nile River are red with lotus flowers. The Lower Nile (North) and the Upper Nile (South) have plants that grow in abundance. The Upper Nile plant is the Egyptian lotus, and the Lower Nile plant is the Papyrus Sedge (Cyperus papyrus), although it is not nearly as plentiful as it once was, and is becoming quite rare.[16]

Several hundred thousand water birds winter in the delta, including the world's largest concentrations of little gulls and whiskered terns. Other birds making their homes in the delta include grey herons, Kentish plovers, shovelers, cormorants, egrets and ibises.

Other animals found in the delta include frogs, turtles, tortoises, mongooses, and the Nile monitor. Nile crocodiles and hippopotamus, two animals which were widespread in the delta during antiquity, are no longer found there. Fish found in the delta include the flathead grey mullet and soles.

Climate

The Delta has a hot desert climate (Köppen: BWh) as the rest of Egypt, but its northernmost part, as is the case with the rest of the northern coast of Egypt which is the wettest region in the country, has relatively moderate temperatures, with highs usually not surpassing 31 °C (88 °F) in the summer. Only 100–200 mm (4–8 in) of rain falls on the delta area during an average year, and most of this falls in the winter months. The delta experiences its hottest temperatures in July and August, with a maximum average of 34 °C (93 °F). Winter temperatures are normally in the range of 9 °C (48 °F) at nights to 19 °C (66 °F) in the daytime. With cooler temperatures and some rain, the Nile Delta region becomes quite humid during the winter months.[17]

Sea level rise

.jpg)

Egypt's Mediterranean coastline experiences significant loss of land to the sea, in some places amounting to 90 m (100 yd) a year. The low-lying Nile Delta area in particular is vulnerable to sea level rise associated with global warming.[18] This effect is exacerbated by the lack of sediments being deposited since the construction of the Aswan Dam. If the polar ice caps were to melt, much of the northern delta, including the ancient port city of Alexandria, could disappear under the Mediterranean. A 30 cm (12 in) rise in sea level could affect about 6.6% of the total land cover area in the Nile Delta region. At 1 m (3 ft 3 in) sea level rise, an estimated 887 thousand people could be at risk of flooding and displacement and about 100 km2 (40 sq mi) of vegetation, 16 km2 (10 sq mi) wetland, 402 km2 (160 sq mi) cropland, and 47 km2 (20 sq mi) of urban area land could be destroyed,[19] flooding approximately 450 km2 (170 sq mi).[20] Some areas of the Nile Delta's agricultural land have been rendered saline as a result of sea level rise; farming has been abandoned in some places, while in others sand has been brought in from elsewhere to reduce the effect. In addition to agriculture, the delta's ecosystems and tourist industry could be negatively affected by global warming. Food shortages resulting from climate change could lead to seven million "climate refugees" by the end of the 21st century. Nevertheless, environmental damage to the delta is not currently one of Egypt's priorities.[21]

The delta's coastline has also undergone significant changes in geomorphology as a result of the reclamation of coastal dunes and lagoons to form new agricultural land and fish farms as well as the expansion of coastal urban areas.[22]

Governorates and large cities

The Nile Delta forms part of these 10 governorates:

Large cities located in the Nile Delta:

References

- Zeidan, Bakenaz. (2006). The Nile Delta in a global vision. Sharm El-Sheikh.

- John Cooper (30 September 2014). The Medieval Nile: Route, Navigation, and Landscape in Islamic Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-977-416-614-3.

- Holz, Robert K (1969). Man-made landforms in the Nile delta. American Geographical Society. OCLC 38826202.

- Location of the site, Kafr Hassan Dawood On-Line, with a map of early sites of the delta.

- "Mysterious temple discovered in the ruins of sunken ancient city". www.9news.com.au. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- History, Laura Geggel 2019-07-29T10:37:58Z. "Divers Find Remains of Ancient Temple in Sunken Egyptian City". livescience.com. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- cowie, ashley. "Subaquatic Temple and Countless Treasures Discovered in Egypt's Sunken City of Heracleion". www.ancient-origins.net. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Santos, Edwin (28 July 2019). "Archaeologists discover a sunken ancient settlement underwater". Nosy Media. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- EDT, Katherine Hignett On 7/23/19 at 11:06 AM (23 July 2019). "Ancient Egypt: Underwater archaeologists uncover destroyed temple in the sunken city of Heracleion". Newsweek. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Topics, Head. "Archaeologists discover a sunken ancient settlement underwater". Head Topics. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Wilson, Ian. The Exodus Enigma (1985), page 46. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- e.g. at Callisthenes Alexander 1.31.

- e.g. in Ptolemy, Geography.

- Hayes, W. 'Most Ancient Egypt', p. 87, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 23 (1964), 73–114.

- City Population website, citing Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics Egypt (web), accessed 11 April 1908.

- "Cyperus papyrus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- Nile Delta Facts

- "Global Warming Threatens Egypt's Coastlines and the Nile Delta". EcoWorld. 25 September 2009. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- Hasan, Emad; Khan, Sadiq Ibrahim; Hong, Yang (2015). "Investigation of potential sea level rise impact on the Nile Delta, Egypt using digital elevation models". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 187 (10): 649. doi:10.1007/s10661-015-4868-9. PMID 26410824.

- "Egypt's Nile Delta falls prey to climate change". 28 January 2010.

- "Egypt fertile Nile Delta falls prey to climate change". Egypt News. 28 January 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- El Banna, Mahmoud M.; Frihy, Omran E. (2009). "Human-induced changes in the geomorphology of the northeastern coast of the Nile delta, Egypt". Geomorphology. 107 (1): 72–78. Bibcode:2009Geomo.107...72E. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.06.025.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nile Delta. |

- "Nile Delta flooded savanna". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- "The Nile Under Control" — 1937 article on controlling the flow of the Nile.

- Adaptationlearning.net: UN project for managing sea level rise risks in the Nile Delta

- "The Nile Delta". Keyway Bible Study. Archived from the original on 2 August 2010.

.jpg)