Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza (also known as the Pyramid of Khufu or the Pyramid of Cheops) is the oldest and largest of the three pyramids in the Giza pyramid complex bordering present-day Giza in Greater Cairo, Egypt. It is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the only one to remain largely intact.

| The Great Pyramid of Giza | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Great Pyramid of Giza in March 2005 | |||||||||||||||

| Khufu | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 29°58′45″N 31°08′03″E | ||||||||||||||

| Ancient name | ʒḫt Ḫwfw Akhet Khufu Khufu's Horizon | ||||||||||||||

| Constructed | c. 2580–2560 BC (4th dynasty) | ||||||||||||||

| Type | True pyramid | ||||||||||||||

| Material | Limestone, granite | ||||||||||||||

| Height |

| ||||||||||||||

| Base | Length of 230.34 metres (756 ft) or 440 Egyptian Royal cubits | ||||||||||||||

| Volume | 2,583,283 cubic metres (91,227,778 cu ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Slope | 51°52'±2'

Building details | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Record height | |||||||||||||||

| Tallest in the world from 2560 BC to 1311 AD[I] | |||||||||||||||

| Surpassed by | Lincoln Cathedral | ||||||||||||||

| Part of | Memphis and its Necropolis – the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur | ||||||||||||||

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, vi | ||||||||||||||

| Reference | 86-002 | ||||||||||||||

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd session) | ||||||||||||||

Based on a mark in an interior chamber naming the work gang and a reference to the Fourth Dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Khufu, Egyptologists believe that the pyramid was built as a tomb over a 10- to 20-year period concluding around 2560 BC. Initially standing at 146.5 metres (481 feet), the Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world for more than 3,800 years until Lincoln Cathedral was finished in 1311 AD. It is estimated that the pyramid weighs approximately 6 million tonnes, and consists of 2.3 million blocks of limestone and granite, some weighing as much as 80 tonnes. Originally, the Great Pyramid was covered by limestone casing stones that formed a smooth outer surface; what is seen today is the underlying core structure. Some of the casing stones that once covered the structure can still be seen around the base. There have been varying scientific and alternative theories about the Great Pyramid's construction techniques. Most accepted construction hypotheses are based on the idea that it was built by moving huge stones from a quarry and dragging and lifting them into place.

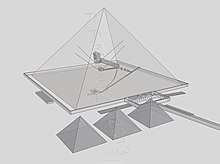

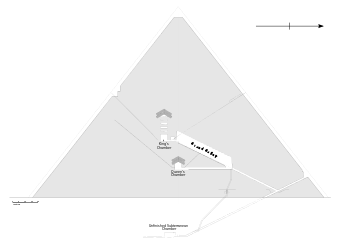

There are three known chambers inside the Great Pyramid. The lowest chamber is cut into the bedrock upon which the pyramid was built and was unfinished. The so-called[2] Queen's Chamber and King's Chamber are higher up within the pyramid structure. The main part of the Giza complex is a set of buildings that included two mortuary temples in honour of Khufu (one close to the pyramid and one near the Nile), three smaller pyramids for Khufu's wives, an even smaller "satellite" pyramid, a raised causeway connecting the two temples, and small mastaba tombs for nobles surrounding the pyramid.

History and description

.svg.png)

Egyptologists believe the pyramid was built as a tomb for the Fourth Dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Khufu (often Hellenized as "Cheops") and was constructed over a 20-year period. Khufu's vizier, Hemiunu (also called Hemon), is believed by some to be the architect of the Great Pyramid.[3] It is thought that, at construction, the Great Pyramid was originally 146.6 metres (481.0 ft) tall, but with the removal of its original casing, its present height is 137 metres (449.5 ft). The lengths of the sides at the base are difficult to reconstruct, given the absence of the casing, but recent analyses put them in a range between 230.26 metres (755.4 ft) and 230.44 metres (756.0 ft). The volume, including an internal hillock, is roughly 2,300,000 cubic metres (81,000,000 cu ft).[4]

The first precision measurements of the pyramid were made by Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie in 1880–82 and published as The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh.[5] Almost all reports are based on his measurements. Many of the casing-stones and inner chamber blocks of the Great Pyramid fit together with extremely high precision. Based on measurements taken on the north-eastern casing stones, the mean opening of the joints is only 0.5 millimetres (0.020 in) wide.[6]

The pyramid remained the tallest man-made structure in the world for over 3,800 years,[7] unsurpassed until the 160-metre-tall (520 ft) spire of Lincoln Cathedral was completed c. 1300. The accuracy of the pyramid's workmanship is such that the four sides of the base have an average error of only 58 millimetres in length.[lower-alpha 1] The base is horizontal and flat to within ±15 mm (0.6 in).[9] The sides of the square base are closely aligned to the four cardinal compass points (within four minutes of arc)[10][lower-alpha 2] based on true north, not magnetic north,[12] and the finished base was squared to a mean corner error of only 12 seconds of arc.[13]

The completed design dimensions, as suggested by Petrie's survey and subsequent studies, are estimated to have originally been 280 Egyptian Royal cubits high by 440 cubits long at each of the four sides of its base. The ratio of the perimeter to height of 1760/280 Egyptian Royal cubits equates to 2π to an accuracy of better than 0.05 percent (corresponding to the well-known approximation of π as 22/7). Some Egyptologists consider this to have been the result of deliberate design proportion. Verner wrote, "We can conclude that although the ancient Egyptians could not precisely define the value of π, in practice they used it".[14] Petrie concluded: "but these relations of areas and of circular ratio are so systematic that we should grant that they were in the builder's design".[15] Others have argued that the ancient Egyptians had no concept of pi and would not have thought to encode it in their monuments. They believe that the observed pyramid slope may be based on a simple seked slope choice alone, with no regard to the overall size and proportions of the finished building.[16] In 2013, rolls of papyrus called the Diary of Merer were discovered written by some of those who delivered limestone and other construction materials from Tora to Giza.[17]

Materials

The Great Pyramid consists of an estimated 2.3 million blocks which most believe to have been transported from nearby quarries. The Tura limestone used for the casing was quarried across the river. The largest granite stones in the pyramid, found in the "King's" chamber, weigh 25 to 80 tonnes and were transported from Aswan, more than 800 km (500 mi) away. Ancient Egyptians cut stone into rough blocks by hammering grooves into natural stone faces, inserting wooden wedges, then soaking these with water. As the water was absorbed, the wedges expanded, breaking off workable chunks. Once the blocks were cut, they were carried by boat either up or down the Nile River to the pyramid.[18] It is estimated that 5.5 million tonnes of limestone, 8,000 tonnes of granite (imported from Aswan), and 500,000 tonnes of mortar were used in the construction of the Great Pyramid.[19]

Casing stones

At completion, the Great Pyramid was surfaced with white "casing stones"—slant-faced, but flat-topped, blocks of highly polished white limestone. These were carefully cut to what is approximately a face slope with a seked of 5+1/2 palms to give the required dimensions. Visibly, all that remains is the underlying stepped core structure seen today. In 1303 AD, a massive earthquake loosened many of the outer casing stones, which in 1356 were carted away by Bahri Sultan An-Nasir Nasir-ad-Din al-Hasan to build mosques and fortresses in nearby Cairo. Many more casing stones were removed from the great pyramids by Muhammad Ali Pasha in the early 19th century to build the upper portion of his Alabaster Mosque in Cairo, not far from Giza. These limestone casings can still be seen as parts of these structures. Later explorers reported massive piles of rubble at the base of the pyramids left over from the continuing collapse of the casing stones, which were subsequently cleared away during continuing excavations of the site.

Nevertheless, a few of the casing stones from the lowest course can be seen to this day in situ around the base of the Great Pyramid, and display the same workmanship and precision that has been reported for centuries. Petrie also found a different orientation in the core and in the casing measuring 193 centimetres ± 25 centimetres. He suggested a redetermination of north was made after the construction of the core, but a mistake was made, and the casing was built with a different orientation.[5] Petrie related the precision of the casing stones as to being "equal to opticians' work of the present day, but on a scale of acres" and "to place such stones in exact contact would be careful work; but to do so with cement in the joints seems almost impossible".[21] It has been suggested it was the mortar (Petrie's "cement") that made this seemingly impossible task possible, providing a level bed, which enabled the masons to set the stones exactly.[22][23]

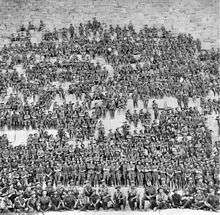

Construction theories

Many alternative, often contradictory, theories have been proposed regarding the pyramid's construction techniques.[24] Many disagree on whether the blocks were dragged, lifted, or even rolled into place. The Greeks believed that slave labour was used, but modern discoveries made at nearby workers' camps associated with construction at Giza suggest that it was built instead by tens of thousands of skilled workers. Verner posited that the labour was organized into a hierarchy, consisting of two gangs of 100,000 men, divided into five zaa or phyle of 20,000 men each, which may have been further divided according to the skills of the workers.[25]

One mystery of the pyramid's construction is its planning. John Romer suggests that they used the same method that had been used for earlier and later constructions, laying out parts of the plan on the ground at a 1-to-1 scale. He writes that "such a working diagram would also serve to generate the architecture of the pyramid with precision unmatched by any other means".[26] He also argues for a 14-year time-span for its construction.[27] A modern construction management study, in association with Mark Lehner and other Egyptologists, estimated that the total project required an average workforce of about 14,500 people and a peak workforce of roughly 40,000. Without the use of pulleys, wheels, or iron tools, they used critical path analysis methods, which suggest that the Great Pyramid was completed from start to finish in approximately 10 years at a rate of up to 3 blocks per minute on certain levels.[28]

Interior

The original entrance to the Great Pyramid is on the north, 17 metres (56 ft) vertically above ground level and 7.29 metres (23.9 ft) east of the center line of the pyramid. From this original entrance, there is a Descending Passage 0.96 metres (3.1 ft) high and 1.04 metres (3.4 ft) wide, which goes down at an angle of 26° 31'23" through the masonry of the pyramid and then into the bedrock beneath it. After 105.23 metres (345.2 ft), the passage becomes level and continues for an additional 8.84 metres (29.0 ft) to the lower Chamber, which appears not to have been finished. There is a continuation of the horizontal passage in the south wall of the lower chamber; there is also a pit dug in the floor of the chamber. Some Egyptologists suggest that this Lower Chamber was intended to be the original burial chamber, but Pharaoh Khufu later changed his mind and wanted it to be higher up in the pyramid.[29]

28.2 metres (93 ft) from the entrance is a square hole in the roof of the Descending Passage. Originally concealed with a slab of stone, this is the beginning of the Ascending Passage. The Ascending Passage is 39.3 metres (129 ft) long, as wide and high as the Descending Passage and slopes up at almost precisely the same angle to reach the Grand Gallery. The lower end of the Ascending Passage is closed by three huge blocks of granite, each about 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) long. One must use the Robbers' Tunnel (see below) to access the Ascending Passage. At the start of the Grand Gallery on the right-hand side there is a hole cut in the wall. This is the start of a vertical shaft which follows an irregular path through the masonry of the pyramid to join the Descending Passage. Also at the start of the Grand Gallery there is the Horizontal Passage leading to the "Queen's Chamber". The passage is 1.1m (3'8") high for most of its length, but near the chamber there is a step in the floor, after which the passage is 1.73 metres (5.7 ft) high.

Queen's Chamber

The "Queen's Chamber"[2] is exactly halfway between the north and south faces of the pyramid and measures 5.75 metres (18.9 ft) north to south, 5.23 metres (17.2 ft) east to west, and has a pointed roof with an apex 6.23 metres (20.4 ft) above the floor. At the eastern end of the chamber there is a niche 4.67 metres (15.3 ft) high. The original depth of the niche was 1.04 metres (3.4 ft), but has since been deepened by treasure hunters.[30]

In the north and south walls of the Queen's Chamber there are shafts, which, unlike those in the King's Chamber that immediately slope upwards (see below), are horizontal for around 2 m (6.6 ft) before sloping upwards. The horizontal distance was cut in 1872 by a British engineer, Waynman Dixon, who believed a shaft similar to those in the King's Chamber must also exist. He was proved right, but because the shafts are not connected to the outer faces of the pyramid or the Queen's Chamber, their purpose is unknown. At the end of one of his shafts, Dixon discovered a ball of black diorite (a type of rock) and a bronze implement of unknown purpose. Both objects are currently in the British Museum.[31]

The shafts in the Queen's Chamber were explored in 1993 by the German engineer Rudolf Gantenbrink using a crawler robot he designed, Upuaut 2. After a climb of 65 m (213 ft),[32] he discovered that one of the shafts was blocked by limestone "doors" with two eroded copper "handles". Some years later the National Geographic Society created a similar robot which, in September 2002, drilled a small hole in the southern door, only to find another door behind it.[33] The northern passage, which was difficult to navigate because of twists and turns, was also found to be blocked by a door.[34]

Research continued in 2011 with the Djedi Project. Realizing the problem was that the National Geographic Society's camera was only able to see straight ahead of it, they instead used a fibre-optic "micro snake camera" that could see around corners. With this they were able to penetrate the first door of the southern shaft through the hole drilled in 2002, and view all the sides of the small chamber behind it. They discovered hieroglyphs written in red paint. They were also able to scrutinize the inside of the two copper "handles" embedded in the door, and they now believe them to be for decorative purposes. They also found the reverse side of the "door" to be finished and polished, which suggests that it was not put there just to block the shaft from debris, but rather for a more specific reason.[35]

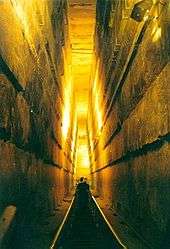

Grand Gallery

The Grand Gallery continues the slope of the Ascending Passage, but is 8.6 metres (28 ft) high and 46.68 metres (153.1 ft) long. At the base it is 2.06 metres (6.8 ft) wide, but after 2.29 metres (7.5 ft) the blocks of stone in the walls are corbelled inwards by 7.6 centimetres (3.0 in) on each side. There are seven of these steps, so, at the top, the Grand Gallery is only 1.04 metres (3.4 ft) wide. It is roofed by slabs of stone laid at a slightly steeper angle than the floor of the gallery, so that each stone fits into a slot cut in the top of the gallery like the teeth of a ratchet. The purpose was to have each block supported by the wall of the Gallery, rather than resting on the block beneath it, in order to prevent cumulative pressure.[36]

At the upper end of the Gallery on the right-hand side there is a hole near the roof that opens into a short tunnel by which access can be gained to the lowest of the Relieving Chambers. The other Relieving Chambers were discovered in 1837–1838 by Colonel Howard Vyse and J.S. Perring, who dug tunnels upwards using blasting powder.

The floor of the Grand Gallery consists of a shelf or step on either side, 51 centimetres (20 in) wide, leaving a lower ramp 1.04 metres (3.4 ft) wide between them. In the shelves there are 54 slots, 27 on each side matched by vertical and horizontal slots in the walls of the Gallery. These form a cross shape that rises out of the slot in the shelf. The purpose of these slots is not known, but the central gutter in the floor of the Gallery, which is the same width as the Ascending Passage, has led to speculation that the blocking stones were stored in the Grand Gallery and the slots held wooden beams to restrain them from sliding down the passage.[37] This, in turn, has led to the proposal that originally many more than 3 blocking stones were intended, to completely fill the Ascending Passage.

At the top of the Grand Gallery, there is a step giving onto a horizontal passage some metres long and approximately 1.02 metres (3.3 ft) in height and width, in which can be detected four slots, three of which were probably intended to hold granite portcullises. Fragments of granite found by Petrie in the Descending Passage may have come from these now-vanished doors.

The Big Void

In 2017, scientists from the ScanPyramids project discovered a large cavity above the Grand Gallery using muon radiography, which they called the "ScanPyramids Big Void". Its length is at least 30 metres (98 ft) and its cross-section is similar to that of the Grand Gallery. Its existence was confirmed by independent detection with three different technologies: nuclear emulsion films, scintillator hodoscopes, and gas detectors.[38][39] The purpose of the cavity is not known and it is not accessible but according to Zahi Hawass it may have been a gap used in the construction of the Grand Gallery.[40] The Japanese research team disputes this, however, saying that the huge void is completely different from the construction spaces previously identified.[41] To verify the "ScanPyramids Big Void" and pinpoint the same, a Japanese team of researchers from Kyushu University, Tohoku University, the University of Tokyo and the Chiba Institute of Technology plans to rescan the structure with a newly developed muon detector in 2020.[42]

King's Chamber

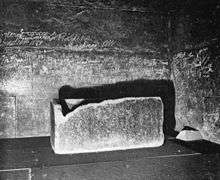

The "King's Chamber"[2] is 20 Egyptian Royal cubits or 10.47 metres (34.4 ft) from east to west and 10 cubits or 5.234 metres (17.17 ft) north to south. It has a flat roof 11 cubits and 5 digits or 5.852 metres (19.20 ft) above the floor. 0.91 m (3.0 ft) above the floor there are two narrow shafts in the north and south walls (one is now filled by an extractor fan in an attempt to circulate air inside the pyramid). The purpose of these shafts is not clear: they appear to be aligned towards stars or areas of the northern and southern skies, yet one of them follows a dog-leg course through the masonry, indicating no intention to directly sight stars through them. They were long believed by Egyptologists to be "air shafts" for ventilation, but this idea has now been widely abandoned in favour of the shafts serving a ritualistic purpose associated with the ascension of the king's spirit to the heavens.[43]

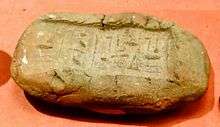

The King's Chamber is entirely faced with granite. Above the roof, which is formed of nine slabs of stone weighing in total about 400 tons, are five compartments known as Relieving Chambers. The first four, like the King's Chamber, have flat roofs formed by the floor of the chamber above, but the final chamber has a pointed roof. Vyse suspected the presence of upper chambers when he found that he could push a long reed through a crack in the ceiling of the first chamber. From lower to upper, the chambers are known as "Davison's Chamber", "Wellington's Chamber", "Nelson's Chamber", "Lady Arbuthnot's Chamber", and "Campbell's Chamber". It is believed that the compartments were intended to safeguard the King's Chamber from the possibility of a roof collapsing under the weight of stone above the Chamber. As the chambers were not intended to be seen, they were not finished in any way and a few of the stones still retain masons' marks painted on them. One of the stones in Campbell's Chamber bears a mark, apparently the name of a work gang.[44][45]

The only object in the King's Chamber is a rectangular granite sarcophagus, one corner of which is damaged. The sarcophagus is slightly larger than the Ascending Passage, which indicates that it must have been placed in the Chamber before the roof was put in place. Unlike the fine masonry of the walls of the Chamber, the sarcophagus is roughly finished, with saw-marks visible in several places. This is in contrast with the finely finished and decorated sarcophagi found in other pyramids of the same period. Petrie suggested that such a sarcophagus was intended but was lost in the river on the way north from Aswan and a hurriedly made replacement was used instead.

Modern entrance

Today tourists enter the Great Pyramid via the Robbers' Tunnel, which was long ago cut straight through the masonry of the pyramid for approximately 27 metres (89 ft), then turns sharply left to encounter the blocking stones in the Ascending Passage. It is possible to enter the Descending Passage from this point, but access is usually forbidden.[46] The origin of this Robbers' Tunnel is the subject of much scholarly discussion. According to tradition, the chasm was cut around 820 AD by Caliph al-Ma'mun's workmen using a battering ram. According to these accounts, al-Ma'mun's digging dislodged the stone fitted in the ceiling of the Descending Passage to hide the entrance to the Ascending Passage and it was the noise of that stone falling and then sliding down the Descending Passage, which alerted them to the need to turn left. Unable to remove these stones, however, the workmen tunneled up beside them through the softer limestone of the Pyramid until they reached the Ascending Passage.[47][48] Due to a number of historical and archaeological discrepancies, many scholars (with Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy perhaps being the first) contend that this story is apocryphal. They argue that it is much more likely that the tunnel had been carved sometime after the pyramid was initially sealed. This tunnel, the scholars continue, was then resealed (likely during the Ramesside Restoration), and it was this plug that al-Ma'mun's ninth century expedition cleared away.[49]

Pyramid complex

The Great Pyramid is surrounded by a complex of several buildings including small pyramids. The Pyramid Temple, which stood on the east side of the pyramid and measured 52.2 metres (171 ft) north to south and 40 metres (130 ft) east to west, has almost entirely disappeared apart from the black basalt paving. There are only a few remnants of the causeway which linked the pyramid with the valley and the Valley Temple. The Valley Temple is buried beneath the village of Nazlet el-Samman; basalt paving and limestone walls have been found but the site has not been excavated.[50][51] The basalt blocks show "clear evidence" of having been cut with some kind of saw with an estimated cutting blade of 15 feet (4.6 m) in length, capable of cutting at a rate of 1.5 inches (38 mm) per minute. Romer suggests that this "super saw" may have had copper teeth and weighed up to 300 pounds (140 kg). He theorizes that such a saw could have been attached to a wooden trestle and possibly used in conjunction with vegetable oil, cutting sand, emery or pounded quartz to cut the blocks, which would have required the labour of at least a dozen men to operate it.[52]

On the south side are the subsidiary pyramids, popularly known as the Queens' Pyramids. Three remain standing to nearly full height but the fourth was so ruined that its existence was not suspected until the recent discovery of the first course of stones and the remains of the capstone. Hidden beneath the paving around the pyramid was the tomb of Queen Hetepheres I, sister-wife of Sneferu and mother of Khufu. Discovered by accident by the Reisner expedition, the burial was intact, though the carefully sealed coffin proved to be empty.

A notable construction flanking the Giza pyramid complex is a cyclopean stone wall, the Wall of the Crow.[53] Lehner has discovered a worker's town outside of the wall, otherwise known as "The Lost City", dated by pottery styles, seal impressions, and stratigraphy to have been constructed and occupied sometime during the reigns of Khafre (2520–2494 BC) and Menkaure (2490–2472 BC).[54][55] In the early 21st century, Mark Lehner and his team made several discoveries, including what appears to have been a thriving port, suggesting the town and associated living quarters, which consisted of barracks called "galleries", may not have been for the pyramid workers after all but rather for the soldiers and sailors who utilized the port. In light of this new discovery, as to where then the pyramid workers may have lived, Lehner suggested the alternative possibility they may have camped on the ramps he believes were used to construct the pyramids or possibly at nearby quarries.[56]

In the early 1970s, the Australian archaeologist Karl Kromer excavated a mound in the South Field of the plateau. This mound contained artefacts including mudbrick seals of Khufu, which he identified with an artisans' settlement.[57] Mudbrick buildings just south of Khufu's Valley Temple contained mud sealings of Khufu and have been suggested to be a settlement serving the cult of Khufu after his death.[58] A worker's cemetery used at least between Khufu's reign and the end of the Fifth Dynasty was discovered south of the Wall of the Crow by Hawass in 1990.[59]

Boats

There are three boat-shaped pits around the pyramid, of a size and shape to have held complete boats, though so shallow that any superstructure, if there ever was one, must have been removed or disassembled. In May 1954, the Egyptian archaeologist Kamal el-Mallakh discovered a fourth pit, a long, narrow rectangle, still covered with slabs of stone weighing up to 15 tons. Inside were 1,224 pieces of wood, the longest 23 metres (75 ft) long, the shortest 10 centimetres (0.33 ft). These were entrusted to a boat builder, Haj Ahmed Yusuf, who worked out how the pieces fit together. The entire process, including conservation and straightening of the warped wood, took fourteen years.

The result is a cedar-wood boat 43.6 metres (143 ft) long, its timbers held together by ropes, which is currently housed in the Giza Solar boat museum, a special boat-shaped, air-conditioned museum beside the pyramid. During construction of this museum, which stands above the boat pit, a second sealed boat pit was discovered. It was deliberately left unopened until 2011 when excavation began on the boat.[60]

Looting

Although succeeding pyramids were smaller, pyramid-building continued until the end of the Middle Kingdom. However, as authors Brier and Hobbs claim, "all the pyramids were robbed" by the New Kingdom, when the construction of royal tombs in a desert valley, now known as the Valley of the Kings, began.[61][62] Joyce Tyldesley states that the Great Pyramid itself "is known to have been opened and emptied by the Middle Kingdom", before the Arab caliph Al-Ma'mun entered the pyramid around 820 AD.[47]

I. E. S. Edwards discusses Strabo's mention that the pyramid "a little way up one side has a stone that may be taken out, which being raised up there is a sloping passage to the foundations". Edwards suggested that the pyramid was entered by robbers after the end of the Old Kingdom and sealed and then reopened more than once until Strabo's door was added. He adds: "If this highly speculative surmise be correct, it is also necessary to assume either that the existence of the door was forgotten or that the entrance was again blocked with facing stones", in order to explain why al-Ma'mun could not find the entrance.[63]

He also discusses a story told by Herodotus. Herodotus visited Egypt in the 5th century BC and recounts a story that he was told concerning vaults under the pyramid built on an island where the body of Cheops lies. Edwards notes that the pyramid had "almost certainly been opened and its contents plundered long before the time of Herodotus" and that it might have been closed again during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt when other monuments were restored. He suggests that the story told to Herodotus could have been the result of almost two centuries of telling and retelling by Pyramid guides.[64]

See also

- Ancient Egypt in mathematics and architecture

- Djedi Project

- Golden ratio in architecture

- Index of Egypt-related articles

- List of archaeoastronomical sites by country

- List of Egyptian pyramids

- List of largest monoliths including a section on calculating the weight of megaliths

- List of tallest freestanding structures

- Pyramid inch

- Pyramidology

- The Upuaut Project

Notes

- Based on side lengths 230.252m, 230.454m, 230.391m, 230.357m.[8]

- For 2600 BC, bisecting the semi-circular path of star 10 Draconis (i Draconis) around the North Celestial Pole during the half-day darkness of a mid-winter evening would easily provide accurate true north.[11] Further sources and discussion available via "Contributions: Dennis Rawlins". DOI. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018.

References

- Verner (2001), p. 189.

- Romer (2007), p. 8. "By themselves, of course, none of these modern labels define the ancient purposes of the architecture they describe."

- Shaw (2003), p. 89

- Lehner & Hawass (2017), pp. 143, 530–531

- Petrie (1883)

- I.E.S. Edwards (1986) [1947]. The Pyramids of Egypt. p. 285.

- Collins (2001), p. 234

- Cole (1925).

- Lehner (1997), p. 108

- Petrie (1883), p. 38

- Rawlins, D.; Pickering, K. (2001). "Astronomical orientation of the pyramids". Nature. 412. 699. doi:10.1038/35089138.

- Petrie (1883), p. 125

- Petrie (1883), p. 39

- Verner (2003), p. 70

- Petrie (1940), p. 30.

- Rossi (2007), p. .

- Stille, Alexander. "The World's Oldest Papyrus and What It Can Tell Us About the Great Pyramids". Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Lehner (1997), p.

- Romer (2007), p. 157

- "British Museum – Limestone block from the pyramid of Khufu". britishmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- Romer (2007), p. 41

- Clarke & Engelbach (1991), pp. 78–79.

- Stocks (2003), pp. 182–183.

- "Building the Great Pyramid". BBC. 3 February 2006. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- Verner (2001), pp. 75–82

- Romer (2007), pp. 327, 329–337

- Romer (2007), p.

- Smith, Craig B. (June 1999). "Project Management B.C." Civil Engineering Magazine. Vol. 69 no. 6. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007.

- "Unfinished Chamber". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- Sharma & Pahuja (2017), p. 38.

- "Lower Northern Shaft". The Upuaut Project. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- "Will the Great Pyramid's Secret Doors Be Opened?". Fox News. 12 December 2011. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

- Gupton, Nancy (4 April 2003). "Ancient Egyptian Chambers Explored". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 3 August 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- "Third "Door" Found in Great Pyramid". National Geographic. 23 September 2002. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- "First images from Great Pyramid's chamber of secrets". New Scientist. Reed Business Information. 25 May 2011. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- Kingsland (1932), p. 71.

- Lehner (1997), p. 113

- "Mysterious Void Discovered in Egypt's Great Pyramid". 2 November 2017. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Morishima, Kunihiro; Kuno, Mitsuaki; Nishio, Akira; Kitagawa, Nobuko; et al. (2 November 2017). "Discovery of a big void in Khufu's Pyramid by observation of cosmic-ray muons". Nature. 552 (7685): 386–390. arXiv:1711.01576. Bibcode:2017Natur.552..386M. doi:10.1038/nature24647. PMID 29160306.

- "Scientists discover hidden chamber in Egypt's Great Pyramid". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "Critics: Nothing special about big void found in Khufu Pyramid:The Asahi Shimbun". Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- "The Hidden Chamber at Giza to be re-scanned and pinpointed". Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Jackson & Stamp (2002), pp. 79, 104

- Vyse (1840), p. .

- "Dallas and Dr Zahi Hawass inside the Great Pyramid". BBC. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- Tyldesley (2007), pp. 38–40

- Tyldesley (2007), p. 38

- Battutah (2002), p. 18.

- Cooperson, Michael (2010). "al-Ma'mun, the Pyramids, and the Hieroglyphs". In Nawas, John (ed.). Occasional Papers of the School of ‘Abbasid Studies Leuven 28 June – 1 July 2004. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. 177. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters. pp. 165–190. OCLC 788203355.

- Arnold (2005), pp. 51–52.

- Arnold, Strudwick & Strudwick (2002), p. 126.

- Romer (2007), pp. 164, 165

- "Wall of the Crow". The Lost City. AERA – Ancient Egypt Research Associates. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- "The Lost City of the Pyramids". The Lost City. AERA – Ancient Egypt Research Associates. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- "Dating the Lost City". The Lost City. AERA – Ancient Egypt Research Associates. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- "Ruins of Bustling Port Unearthed at Egypt's Giza Pyramids". Livescience.com. 28 January 2014. Archived from the original on 3 October 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- Hawass, Zahi (1999). "Giza, workmen's community". In Kathryn A. Bard (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London/New York. pp. 423–426. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

- Hawass & Senussi (2008), pp. 127–128.

- Hawass, Zahi. "The Discovery of the Tombs of the Pyramid Builders at Giza". Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- "Khufu's Second Boat". Institute of Egyptology. Tokyo: Waseda University. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Brier & Hobbs (1999), p. 164.

- Cremin (2007), p. 96.

- Edwards (1986), pp. 99–100

- Edwards (1986), pp. 990–91

Bibliography

- Arnold, Dieter (2005). Temples of Ancient Egypt. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-945-5.

- Arnold, Dieter; Strudwick, Nigel; Strudwick, Helen (2002). The encyclopaedia of ancient Egyptian architecture. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-465-8.

- Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. ISBN 978-0-330-41879-9.

- Brier, Bob; Hobbs, A. Hoyt (1999). Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30313-5.

- Cole, J.H. (1925). Determination of the Exact Size and Orientation of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Cairo: Government Press. SURVEY OF EGYPT Paper No. 39.

- Clarke, Somers; Engelbach, Reginal (1991). Ancient Egyptian construction and architecture. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-26485-1.

- Collins, Dana M. (2001). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Cremin, Aedeen (2007). Archaeologica: The World's Most Significant Sites and Cultural Treasures. Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-2822-1.

- Edwards, I.E.S. (1986) [1962]. The Pyramids of Egypt. Max Parrish.

- Hawass, Zahi; Senussi, Ashraf (2008). Old Kingdom Pottery from Giza. Supreme Council of Antiquities. ISBN 978-977-305-986-6.

- Jackson, K.; Stamp, J. (2002). Pyramid : Beyond Imagination. Inside the Great Pyramid of Giza. BBC Worldwide Ltd. ISBN 978-0-563-48803-3.

- Kingsland, William (1932). The Great pyramid in fact and in theory. London: Rider. ISBN 978-0-7873-0497-3.

- Lehner, Mark (1997). The Complete Pyramids. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

- Lehner, Mark; Hawass, Zahi (2017). Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-42569-6.

- Petrie, William Matthew Flinders (1883). The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh. Field & Tuer. ISBN 0-7103-0709-8.

- Petrie, William Matthew Flinders (1940). Wisdom of the Egyptians. British school of archaeology in Egypt and B. Quaritch Limited.

- Romer, John (2007). The Great Pyramid: Ancient Egypt Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87166-2.

- Rossi, Corina (2007). Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69053-9.

- Sharma, Sehdev; Pahuja, Damanjit Kaur (2017). Five Great Civilizations of Ancient World. Educreation Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61813-837-8.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- Stocks, Denys Allen (2003). Experiments in Egyptian archaeology: stoneworking technology in ancient Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30664-5.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2007). Egypt: How a lost civilization was rediscovered. BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-52257-7.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-1703-1.

- Verner, Miroslav (2003). The Pyramids: Their Archaeology and History. Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-84354-171-8.

- Vyse, H. (1840). Operations Carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837: With an Account of a Voyage into Upper Egypt, and an Appendix. I. London: J. Fraser. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

Further reading

- Bauval, Robert; Hancock, Graham (1996). Keeper of Genesis. Mandarin books. ISBN 0-7493-2196-2.

- Calter, Paul A. (2008). Squaring the Circle: Geometry in Art and Architecture. Key College Publishing. ISBN 1-930190-82-4.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05074-0.

- Cooper, Roscoe; Cooper, Vicki Teague; Croll, Carolyn; Patch, Diana Craig; Tehon, Atha (1997). The Great Pyramid: An Interactive Book. London: British Museum Press.

- Der Manuelian, Peter (2017). Digital Giza: Visualizing the Pyramids. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gahlin, Lucia (2003). Myths and Mythology of Ancient Egypt. Anness Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84215-831-7.

- Hassan, Selim (1960). The Great Pyramid of Khufu and its Mortuary Chapel With Names and Titles of Vols. I–X of the Excavations at Giza (PDF). Ministry of Culture and National Orientation, Antiquities Department of Egypt. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2013.

- Hawass, Zahi A. (2006). Mountains of the Pharaohs: The Untold Story of the Pyramid Builders. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

- Levy, Janey (2005). The Great Pyramid of Giza: Measuring Length, Area, Volume, and Angles. Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 1-4042-6059-5.

- Lepre, J.P. (1990). The Egyptian Pyramids: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Reference. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-89950-461-2.

- Lightbody, David I (2008). Egyptian Tomb Architecture: The Archaeological Facts of Pharaonic Circular Symbolism. British Archaeological Reports International Series S1852. ISBN 978-1-4073-0339-0.

- Nell, Erin; Ruggles, Clive (2014). "The Orientations of the Giza Pyramids and Associated Structures". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 45 (3): 304–360.

- Oakes, Lorana; Lucia Gahlin (2002). Ancient Egypt. Hermes House. ISBN 1-84309-429-0.

- Petrie, W.M. Flinders (2006). The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh. Worcester, UK: Yare Egyptology.

- Rossi, Corinna; Accomazzo, Laura (2005). The Pyramids and the Sphinx (English ed.). Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

- Scarre, Chris (1999). The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World. Thames & Hudson, London. ISBN 978-0-500-05096-5.

- Seidelmann, P. Kenneth (1992). Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac. University Science Books. ISBN 0-935702-68-7.

- Siliotti, Alberto (1997). Guide to the pyramids of Egypt; preface by Zahi Hawass. Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 0-7607-0763-4.

- Smyth, Piazzi (1978). The Great Pyramid. Crown Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-517-26403-X.

- Wirsching, Armin (2009). Die Pyramiden von Giza – Mathematik in Stein gebaut (2nd ed.). Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-8370-2355-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Pyramid of Giza. |

| Library resources about Great Pyramid of Giza |

- Pyramids at Curlie

- Building the Khufu Pyramid

- "The Giza Plateau Mapping Project". Oriental Institute.

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Red Pyramid |

World's tallest structure c. 2570 BC − 1300 AD 146.6 m |

Succeeded by Lincoln Cathedral |

.jpg)