Song Yingxing

Song Yingxing (Traditional Chinese: 宋應星; Simplified Chinese: 宋应星; Wade Giles: Sung Ying-Hsing; 1587-1666 AD) was a Chinese scientist and encyclopedist who lived during the late Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). He was the author of Tiangong Kaiwu, an encyclopedia that covered a wide variety of technical subjects, including the use of gunpowder weapons.[1] The British sinologist and historian Joseph Needham called Song Yingxing "The Diderot of China."[2]

Song Yingxing | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1587 |

| Died | 1666 |

| Known for | Encyclopedist, scientist |

Biography

Song Yingxing was born in Yichun of Jiangxi in 1587 to a gentry family of reduced circumstances, he participated in the imperial examinations, and passed the provincial test in 1615, at the age of 28.[3] He achieved only modest wealth and influence during his life. However, he was repeatedly unsuccessful in the metropolitan examination. Song sat for the test five times, the last being in 1631 at the age of 44.[3] After this last failure, he held a series of minor positions in provincial government. The works for which Song is known today all date from 1636 to 1637. The repeated trips to the capital to participate in the metropolitan examination likely provided him with the broad base of knowledge demonstrated in the works. Song retired from public life in 1644, after the fall of the Ming dynasty.[3]

Song's life and work coincided with the end of the Ming dynasty. While the empire was ultimately toppled by a series of succession crises, many historians noted that the collapse followed a period characterized by “indulgence and the lust for luxury goods”.[4] Song’s family life in many ways mirrored the imperial decay. Nonetheless, the late Ming dynasty was still culturally vibrant and there was great demand for specialized craft goods. Also the state placed heavy regulations and taxes on the various craft industries Song profiled in his encyclopedia. His life also coincided with a period of rising literacy and education, despite increased economic strain. For many scholars, a life of simplicity and frugality was considered an ideal. Further, the study of subjects like agriculture and handicrafts was considered a worthy pursuit, since it was expected that the social elite should respect their obligation to care for the common folk [5]

Song’s repeated examinations were common for the time, as the required exams were incredibly competitive, despite their formulaic nature. It was common for would-be civil servants to attempt the exams even into their 40s. His treks to and from the capital for these exams not only allowed him to interact will all manner of laborers and craftsmen, but also exposed him to the realities of the declining empire. Marauding bands and encroaching tribes people threatened China in the north, while peasant revolts and invasions plagued the south. Even in Beijing, the twisting and turning machinations of those vying for power often spilled over into the scholarly realm, sometimes subjecting them to expulsion.[6]

Written works

Encyclopedias

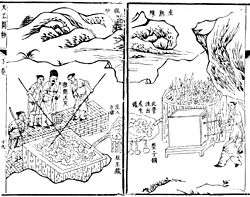

Although Song Yingxing's encyclopedia was a significant publication for his age, there had been a long tradition in the history of Chinese literature in creating large encyclopedic works. For example, the Four Great Books of Song compiled much earlier in the 10th and 11th centuries (and all four combined, were much more extensive in size than his work). Just a few decades before Yingxing's work, there was also the Ming Dynasty encyclopedia of the Sancai Tuhui, written in 1607 and published in 1609. Song Yingxing's famous work was the Tiangong Kaiwu, or The Exploitation of the Works of Nature, published in May 1637 with funding provided by Song's patron Tu Shaokui.[1][7][8] The Tiangong Kaiwu is an encyclopedia covering a wide range of technical issues, including the use of various gunpowder weapons. Copies of the book were very scarce in China during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) (due to the government's establishment of monopolies over certain industries described in the book), but original copies of the book were preserved in Japan.[9]

As the historian Joseph Needham points out, the vast amount of accurately drawn illustrations in this encyclopedia dwarfed the amount provided in previous Chinese encyclopedias, making it a valuable written work in the history of Chinese literature.[9] At the same time, the Tiangong Kaiwu broke from Chinese tradition by rarely referencing previous written work. It is instead written in a style strongly suggestive of first-hand experience. In the preface to the work, Song attributed this deviation from tradition to his poverty and low standing.[3]

Cosmology

Song Yingxing also published two scientific tractates that outline his cosmological views. In these, he discusses the concepts of qi and xing (形). Qi has been described in many different ways by Chinese philosophers. To Song, it is a type of all-permeating vapor from which solid objects (xing) are formed. These solid objects eventually return to the state of qi, which itself eventually returns to the great void. Some objects, such as the sun and the moon, remain in qi form indefinitely, while objects like stones are eternally xing. Some objects, like water and fire, are intermediary between the two forms.[3]

See also

- List of Chinese people

- History of science and technology in China

- Huolongjing

- History of gunpowder

- Gunpowder warfare

- History of agriculture

- History of ferrous metallurgy

- Wang Zhen (official)

References

Citations

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 36.

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 102.

- Cullen, Christopher (1990). "The Science/Technology Interface in Seventeenth-Century China: Song Yingxing 宋 應 星 on "qi" 氣 and the "wu xing" 五 行". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 53 (2): 295–318. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00026100. JSTOR 619236.

- Schäfer, Dagmar (2011). The Crafting of the 10,000 Things: : Knowledge and Technology in Seventeenth-Century China. p. 24.

- Schäfer. The Crafting of the 10,000 Things. p. 30.

- Schäfer. The Crafting of the 10,000 Things. pp. 36–37.

- Song, Yingxing (1637). "The Exploitation of the Works of Nature (Tiangong Kaiwu)". World Digital Library (in Chinese). Jiangxi Sheng, China. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- Song, xiv.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 172.

Bibliography

- Brook, Timothy. (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22154-0

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Song, Yingxing, translated with preface by E-Tu Zen Sun and Shiou-Chuan Sun (1966). T'ien-Kung K'ai-Wu: Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.