Shenzhou program

The Shenzhou program (/ˈʃɛnˈdʒoʊ/,[1] Chinese: 神舟) is a crewed spaceflight initiative by China. The program put the first Chinese citizen, Yang Liwei, into orbit on 15 October 2003.

| Shenzhou program | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 神舟 | ||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | shénzhōu | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The development began in 1992, under the name of Project 921-1. The Chinese National Manned Space Program was given the designation Project 921 with Project 921-1 as its first significant goal. The plan called for a crewed launch in October 1999, prior to the new millennium.

Russian assistance to the program began as early as May 1991, when Russian lecturers briefed the Chinese engineers on the capabilities and potential of their Soyuz spacecraft.[2] This was followed by two-year fellowships for 20 young Chinese engineers in Russia during 1992–1994. In September 1994 Chinese President Jiang Zemin visited the Russian Flight Control Centre in Kaliningrad and noted that there were broad prospects for co-operation between the two countries in space. In March 1995 a deal was signed to transfer manned spacecraft technology to China.[3][4] Included in the agreement were training of cosmonauts, provision of Soyuz spacecraft capsules and life support systems, androgynous docking systems, and space suits.

The first four uncrewed test flights happened in 1999, 2001, and 2002. These were followed by crewed missions. Shenzhou missions are launched on the Long March 2F from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. The command center of the mission is the Beijing Aerospace Command and Control Center. The China Manned Space Engineering Office provides engineering and administrative support for the crewed Shenzhou missions.[5]

The name Shenzhou is variously translated as Divine vessel,[6] Divine craft,[7] or Divine ship.[8]

History

China's first efforts at human spaceflight started in 1968 with a projected launch date of 1973. Although China did launch an uncrewed satellite in 1970 and has maintained an active uncrewed program since, the crewed spaceflight program was cancelled due to lack of funds and political interest. Instead, China decided in 1978 to pursue a method of sending astronauts into space using the more familiar FSWderived ballistic reentry capsules. Two years later. in 1980, the Chinese government cancelled the program citing cost concerns.[9]

The current Chinese human spaceflight program was authorized on 1 April 1992 as Project 921–1, with work beginning on 1 January 1993. The initial plan has three phases:[10]

- Phase 1 would involve launch of two uncrewed versions of the crewed spacecraft, followed by the first Chinese crewed spaceflight, by 2002.

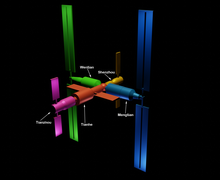

- Phase 2 would run through 2007, and involve a series of flights to prove the technology, conduct rendezvous and docking operations in orbit, and operate an 8-ton spacelab using the basic spacecraft technology.

- Phase 3 would involve orbiting of a 20-ton space station in the 2010–2015 period, with crews being shuttled to it using the 8-ton crewed spacecraft.

The chief designers include Qi Faren and Wang Yongzhi. The first uncrewed flight of the spacecraft was launched on 19 November 1999, after which Project 921-1 was renamed Shenzhou, a name reportedly chosen by Jiang Zemin. A series of three additional uncrewed flights ensued. The Shenzhou reentry capsules used are 13% larger than Soyuz reentry capsules, and it is expected that later craft will be designed to carry a crew of four instead of Soyuz's three, although physical limitations on astronaut size, as experienced with earlier incarnations of Soyuz, will likely apply.

The fifth launch, Shenzhou 5, was the first to carry a human (Yang Liwei) and occurred at 01:00:00 UTC on 15 October 2003.[11]

Like similar space programs in other nations, Shenzhou has raised some questions about whether China should spend money on launching people into space, arguing that these resources would be better directed elsewhere. Indeed, two earlier human spaceflight programs, one in the mid-1970s and the other in the 1980s, were cancelled because of expense. In response, several justifications have been offered in the Chinese media. One is that the long-term destiny of humanity lies in the exploration of space, and that China should not be left behind. Another is that such a program will catalyze the development of science and technology in China. Finally, it has been argued that the prestige resulting from this capability will increase China's stature in the world, in a similar manner to the 2008 Olympics.

On 17 October 2005, following the success of Shenzhou 6, Chinese media officially stated that the cost of this flight was around US$110 million, and the gross cost of Project 921/1 in the past 11 years was US$2.3 billion. These values are lower than the cost of similar space programs in other nations.

The Chinese media has heavily promoted the experiments undertaken by Shenzhou, particularly exposing seeds, including some from Taiwan, to zero gravity and radiation. Most scientists, however, discount the usefulness of this type of experiment.

The experience during the 1960s of both the United States with the Manned Orbiting Laboratory and the Soviet Union with the Almaz space station suggests that the military usefulness of human spaceflight is quite limited and that practically all military uses of space are much more effectively performed by uncrewed satellites. Thus while the Shenzhou orbital module could be used for military reconnaissance, there appears to be no military reason for incorporating such a system in a crewed mission, as China could use purely uncrewed satellites for these purposes.

Shenzhou spacecraft

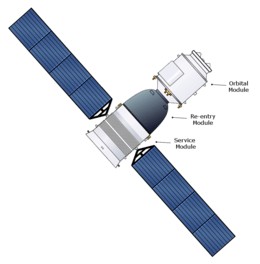

The Shenzhou spacecraft resembles the Russian Soyuz, although it is larger. Unlike the Soyuz, it features a powered orbital module capable of autonomous flight.

Like Soyuz, Shenzhou consists of three modules: a forward orbital module (轨道舱), a reentry capsule (返回舱) in the middle, and an aft service module (推进舱). This division is based on the principle of minimizing the amount of material to be returned to Earth. Anything placed in the orbital or service modules does not require heat shielding, and this greatly increases the space available in the spacecraft without increasing weight as much as it would need to be if those modules needed to withstand reentry.

Missions launched

| Patch | Mission | Launch | Duration | Landing | Crew | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shenzhou 1 | 19 November 1999 | 21 h 11 m | 20 November 1999 | N/A | Uncrewed test flight | |

| Shenzhou 2 | 9 January 2001 | 7 d 10 h 22 m | 16 January 2001 | N/A | Carried scientific payload including monkey, dog, rabbit and other animals. | |

| Shenzhou 3 | 25 March 2002 | 6 d 18 h 51 m | 1 April 2002 | N/A | Carried a test dummy. | |

| Shenzhou 4 | 29 December 2002 | 6 d 18 h 36 m | 5 January 2003 | N/A | Carried a test dummy and several science experiments. | |

| Shenzhou 5 | 15 October 2003 | 21 h 22 m 45 s | 15 October 2003 | First Chinese crewed flight, 14 Earth orbits. | ||

| Shenzhou 6 | 12 October 2005 | 4 d 19 h 33 m | 16 October 2005 | Multiple days in space, 75 orbits. | ||

| Shenzhou 7 | 25 September 2008 | 2 d 20 h 27 m | 28 September 2008 | First three-person crew, first Chinese spacewalk. | ||

| Shenzhou 8 | 31 October 2011 | 16 d 13 h 34 m | 17 November 2011 | N/A | Uncrewed mission, rendezvoused and docked with Tiangong-1. | |

| Shenzhou 9 | 16 June 2012 | 12 d 15 h 24 m | 29 June 2012 | First Chinese woman in space; first repeated flight; first crewed docking with Tiangong-1 space station, 18 June 2012, 06:07 UTC.[12] | ||

| Shenzhou 10 | 11 June 2013 | 14 d 14 h 29 m | 26 June 2013 | Second Chinese woman in space; second crewed docking with Tiangong-1 space station. | ||

| Shenzhou 11 | 17 October 2016 | 32 d 06 h 29 m | 18 November 2016 | First and only crewed docking with Tiangong-2 space station, crew set record for longest Chinese crewed spaceflight. |

Future missions

| Patch | Mission | Launch | Duration | Landing | Crew | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shenzhou 12 | 2021 | TBA | NET 2021 | Scheduled to visit Tianhe-1 to begin construction of the Chinese Space Station, crew has already been selected and will be announced closer to launch.[13] | ||

| Shenzhou 13 | 2021 | TBA | NET 2021 | Will continue construction of the Chinese Space Station. | ||

| Shenzhou 14 | 2022 | TBA | NET 2022 | Will continue construction of the Chinese Space Station. | ||

| Shenzhou 15 | 2022 | TBA | NET 2022 | Will be the final of four scheduled crewed Shenzhou missions dedicated to construction of the Chinese Space Station.[14] | ||

| Shenzhou 16 | 2023 | TBA | NET 2023 | Will deliver the first long-duration crew to the Chinese Space Station. | ||

Astronauts

November 1996 trainer selection

There were two astronaut trainers selected for Project 921. They trained at the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonauts Training Center in Russia.

- Li Qinglong – born August 1962 in Dingyuan, Anhui Province and PLAAF interceptor pilot and space instructor at Star City

- Wu Jie

January 1998 astronaut candidate selection

- Chen Quan

- Deng Qingming – from Jiangxi Province and PLAAF pilot, back up on Shenzhou 11

- Fei Junlong – second Chinese astronaut, commander of Shenzhou 6

- Jing Haipeng – born October 1966 and PLAAF pilot, astronaut of Shenzhou 7, Shenzhou 9 and Shenzhou 11

- Liu Boming – born September 1966 and PLAAF pilot, astronaut of Shenzhou 7

- Liu Wang – born in Shanxi Province and PLAAF pilot, flew on Shenzhou 9

- Nie Haisheng – back up in Shenzhou 5, flight engineer on Shenzhou 6, commander of Shenzhou 10

- Pan Zhanchun – PLAAF pilot

- Yang Liwei – first man sent into space by the space program of China on Shenzhou 5, made the PRC the third country to independently send people into space

- Zhai Zhigang – back up in Shenzhou 5, commander of Shenzhou 7

- Zhang Xiaoguang – born in Liaoning Province and PLAAF pilot, flew on Shenzhou 10

- Zhao Chuandong – PLAAF pilot

2010 astronaut candidate selection

- Cai Xuzhe

- Chen Dong – flew on Shenzhou 11

- Liu Yang – first Chinese woman into space, flew on Shenzhou 9

- Tang Hongbo – back up on Shenzhou 11

- Wang Yaping – second Chinese woman into space, flew on Shenzhou 10

- Yi Guangfu

- Zhang Hu

See also

- Long March rocket

- Tiangong program

- Space program of China

- China National Space Administration

- Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics

References

- Specific

- "Shenzhou pronunciation". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2015-04-25.

- "Shenzhou". Astronautix. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Shenzhou". Astronautix. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Shenzhou Manned Spacecraft Programme". Aerospace Technology. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "China's Manned Space Program Takes the Stage at 26th National Space Symposium". The Space Foundation. 2010-04-10. Archived from the original on 2010-04-12.

- "Expedition 7 Crew Members Welcome China to Space". NASA. 17 October 2003. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Scuka, Daniel (26 March 2018). "Tiangong-1 frequently asked questions". ESA. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "China's Shenzhou spacecraft – the "divine ship"". New Scientist. 12 October 2005. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120419165427/http://www.futron.com/upload/wysiwyg/Resources/Whitepapers/China_n_%20Second_Space_Age_1003.pdf - 5 May 2020

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120419165427/http://www.futron.com/upload/wysiwyg/Resources/Whitepapers/China_n_%20Second_Space_Age_1003.pdf - 5 May 2020

- "Shenzhou 5: Trajectory 2003-045A". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. NASA. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Jonathan Amos (18 June 2012). "Shenzhou-9 docks with Tiangong-1". BBC. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- https://twitter.com/AJ_FI/status/1257644667258261510

- "China launches new Long March-5B rocket for space station program".

- General

- "Shenzhou". Archived from the original on 13 October 2005. Retrieved 21 July 2005.

- "China's first astronaut revealed". BBC. 7 March 2003.

- "Brief history of Russian aid to Chinese space program". Archived from the original on 8 April 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- "Details on purchase of Soyuz descent capsule by China, Space.com". Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shenzhou. |

- Flickr: Photos tagged with shenzhou, photos likely relating to Shenzhou spacecraft

.jpg)