Space toilet

A space toilet or zero gravity toilet is a toilet that can be used in a weightless environment. In the absence of weight, the collection and retention of liquid and solid waste is directed by use of airflow. Since the air used to direct the waste is returned to the cabin, it is filtered beforehand to control odour and cleanse bacteria. In older systems, wastewater is vented into space, and any solids are compressed and stored for removal upon landing. More modern systems expose solid waste to vacuum pressures to kill bacteria, which prevents odor problems and kills pathogens.[1]

.jpg)

Background

Astronauts say that they are most often asked how they go to the bathroom in space.[2] In space, weightlessness causes fluids to distribute uniformly around human bodies. Kidneys detect the fluid movement and a physiological reaction causes the humans to need to relieve themselves within two hours of departure from Earth. The space toilet was thus the first device activated on shuttle flights, after astronauts unbuckled themselves.[3]

Basic parts

There are four basic parts in a space toilet: the liquid waste vacuum tube, the vacuum chamber, the waste storage drawers, and the solid waste collection bags. The liquid waste vacuum tube is a 2 to 3-foot (0.91 m) long rubber or plastic hose that is attached to the vacuum chamber and connected to a fan that provides suction. At the end of the tube there is a detachable urine receptacle, which come in different versions for male and female astronauts. The male urine receptacle is a plastic funnel two to three inches in width and about four inches deep. A male astronaut urinates directly into the funnel from a distance of two or three inches away. The female funnel is oval and is two inches by four inches wide at the rim. Near the funnel's rim are small holes or slits that allow air movement to prevent excessive suction. The vacuum chamber is a cylinder about 1-foot (0.30 m) deep and six inches wide with clips on the rim where waste collection bags may be attached and a fan that provides suction. Urine is pumped into and stored in waste storage drawers. Solid waste is stored in a detachable bag made of a special fabric that lets gas (but not liquid or solid) escape, a feature that allows the fan at the back of the vacuum chamber to pull the waste into the bag. When the astronaut is finished, he or she then twists the bag and places it in a waste storage drawer. Samples of urine and solid waste are frozen and taken to Earth for testing.

Designs

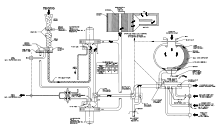

Space Shuttle Waste Collection System

The toilet used on the Space Shuttle is called the Waste Collection System (WCS). In addition to air flow, it also uses rotating fans to distribute solid waste for in-flight storage. Solid waste is distributed in a cylindrical container which is then exposed to vacuum to dry the waste.

The WCS required many hours of training. For urination, a hose was used. For defecation, with a 4 inches (100 mm) diameter for the hole in the seat—much smaller than in a conventional toilet—the user's bottom needed to be exactly centered on the seat. NASA built a simulator with a video camera in the hole; those training used a crosshair to learn how to position their bodies, while other astronauts watched and made jokes.[5][2]

Liquid waste is vented to space. During STS-46, one of the fans malfunctioned, and crew member Claude Nicollier was required to perform in-flight maintenance (IFM). An earlier, complete failure, on the eight-day STS-3 test flight, forced its two-man crew (Jack Lousma and Gordon Fullerton) to use a fecal containment device (FCD) for waste elimination and disposal.

International Space Station

There are two toilets on the International Space Station, located in the Zvezda and Tranquility modules.[6] They use a fan-driven suction system similar to the Space Shuttle WCS. Liquid waste is collected in 20-litre (5.3 US gal) containers. Solid waste is collected in individual micro-perforated bags which are stored in an aluminum container.[7] Full containers are transferred to Progress for disposal. An additional Waste and Hygiene Compartment is part of the Tranquility module launched in 2010. In 2007, NASA purchased a Russian-made toilet similar to the one already aboard ISS rather than develop one internally.[8]

On May 21, 2008, the gas liquid separator pump failed on the 7-year-old toilet in Zvezda, although the solid waste portion was still functioning. The crew attempted to replace various parts, but was unable to repair the malfunctioning part. In the interim, they used a manual mode for urine collection.[9] The crew had other options: to use the toilet on the Soyuz transport module (which only has capacity for a few days of use) or to use urine-collection bags as needed.[10] A replacement pump was sent from Russia in a diplomatic pouch so that Space Shuttle Discovery could take it to the station as part of mission STS-124 on June 2.[11][12][13]

Other designs

The Soviet/Russian Space Station Mir's toilet also used a system similar to the WCS.[14]

While the Soyuz spacecraft had an onboard toilet facility since its introduction in 1967 (due to the additional space in the Orbital Module), all Gemini and Apollo spacecraft required astronauts to urinate in a so-called "relief tube" in which the contents were dumped into space (an example would be the urine dump scene in the movie Apollo 13), while fecal matter was collected in specially-designed bags.[15] The facilities were so uncomfortable that, to avoid using them, astronauts ate less than half the available food on their flights.[16] The Skylab space station, used by NASA between May 1973 and March 1974, had an onboard WCS facility which served as a prototype for the Shuttle's WCS, but also featured an onboard shower facility. The Skylab toilet, which was designed and built by the Fairchild Republic Corp. on Long Island, was primarily a medical system to collect and return to Earth samples of urine, feces and vomit so that calcium balance in astronauts could be studied.

Even with the facilities, astronauts and cosmonauts for both launch systems employ pre-launch bowel clearing and low-residue diets to minimize the need for defecation.[17] The Soyuz toilet has been used on a return mission from Mir.[14]

NPP Zvezda is a Russian developer of space equipment, which includes zero-gravity toilets.[18]

A next-generation space toilet called the Universal Waste Management System (UWMS) is being developed by NASA for Orion and other long duration missions.[19] It is planned to be quieter, lighter, more reliable, more hygienic and more compact than previous systems.[19][20] A flight test article of the UWMS is planned to be delivered and tested on the ISS in 2018.[19]

Toilet device on Soyuz spacecraft.

Toilet device on Soyuz spacecraft.- Space Shuttle toilet.

- Russian space toilet used in space station MIR.

A mockup of the toilet that would be carried on MOL.

A mockup of the toilet that would be carried on MOL. Zero Gravity Toilet on the International Space Station in the Zvezda Service Module.

Zero Gravity Toilet on the International Space Station in the Zvezda Service Module. Space toilet inside Node 3, after relocation from the US lab.

Space toilet inside Node 3, after relocation from the US lab.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Space toilets. |

References

- "Gigapan: Space Shuttle Discovery Toilet". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- Shuttle's Toilet Requires Special Training (YouTube). NASA. May 5, 2010.

- Walker, Charles D. (March 17, 2005). "Oral History 2 Transcript" (PDF). NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project (Interview). Interviewed by Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- NASA (November 15, 2001). "Configuration Changes and Certification Status – Shuttle Urine Pre-treat Assembly" (PDF). STS-108 Flight Readiness Review. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- Croft, Melvin; Youskauskas, John (2019). Come Fly with Us: NASA's Payload Specialist Program. Outward Odyssey: a People's History of Spaceflight. University of Nebraska Press. p. 15. ISBN 9781496212252.

- Cheryl L. Mansfield (November 7, 2008). "Station Prepares for Expanding Crew". NASA. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- Lu, Ed (September 8, 2003). "HSF – International Space Station – "Greetings Earthling"". Retrieved December 21, 2006.

- Fareastgizmos.com (July 6, 2007). "19 million US Dollars for a space station toilet". Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- "Toilet trouble for space station". BBC News. May 29, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- "Space station struggles with balky toilet".

- "Astronauts To Fix Space Station Toilet". Archived from the original on September 19, 2008.

- "ISS – Zvezda Bathroom Repairs and Shuttle Preps for Crew".

- "Space Station Toilet Parts Set for Liftoff". May 29, 2008.

- Shuttleworth, Mark (February 9, 2002). "Toilet Training". First African in Space. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- Sandra Häuplik-Meusburger: Architecture for astronauts : an activity-based approach. Springer, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7091-0666-2, Hygiene Apollo - Resume Toilett, p.134-137

- Bourland, Charles T. (April 7, 2006). "Charles T. Bourland". NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project (Interview). Interviewed by Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- "Low Residue Diet". Buzzle.com. December 15, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- "Assenisation Sanity Unit ASU-8A". Zvezda-npp.ru. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- James L. Broyan, Jr.; Michael K. Ewert; Patrick W. Fink (August 4, 2014). "Logistics Reduction Technologies for Exploration Missions" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- Thomas J. Stapleton; Shelley Baccus; James L. Broyan, Jr. (January 1, 2013). "Development of a Universal Waste Management System" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved September 28, 2014.