Brazilian Space Agency

The Brazilian Space Agency (Portuguese: Agência Espacial Brasileira; AEB) is the civilian authority in Brazil responsible for the country's space program. It operates a spaceport at Alcântara, and a rocket launch site at Barreira do Inferno. The agency has given Brazil a role in space in South America and made Brazil a former partner for cooperation in the International Space Station.[4]

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Abbreviation |

|

| Formed | 10 February 1994[1] (formerly the Brazilian space program, 1961-1993) |

| Type | Space agency |

| Headquarters | Brasília, Distrito Federal |

| Official language | Portuguese |

| Administrator | Carlos Augusto Teixeira de Moura[2] |

| Primary spaceport | Alcântara Launch Center |

| Owner | Government of Brazil |

| Annual budget | R$179.334 million / US$46.702 million (2019)[3] |

| Website | www.aeb.gov.br |

The Brazilian Space Agency is the heir to Brazil's space program. Previously, the program had been under the control of the Brazilian military; the program was transferred into civilian control on 10 February 1994.

It suffered a major setback in 2003, when a rocket explosion killed 21 technicians. Brazil successfully launched its first rocket into space on 23 October 2004 from the Alcântara Launch Center; it was a VSB-30 launched on a sub-orbital mission. Several other successful launches have followed.[5][6][7]

On March 30, 2006, AEB astronaut Marcos Pontes became the first Brazilian and the first native Portuguese-speaking person to go into space, where he stayed on the International Space Station for a week. During his trip, Pontes carried out eight experiments selected by the Brazilian Space Agency. These experiments included testing flight dynamics of saw blades in zero gravity environments, and attempting to "tip over" a table of space food". He landed in Kazakhstan on April 8, 2006, with the crew of Expedition 12.[8]

The Brazilian Space Agency has pursued a policy of joint technological development with more advanced space programs. Initially, it relied heavily on the United States, but after meeting difficulties from them on technological transfers, Brazil has branched out, working with other nations, including China, India, Russia, and Ukraine.

History

The then president Jânio Quadros in 1960 established a commission that elaborated a national program for the space exploration. As a result of this work, in August 1961, the Organization Group of the National Commission of Space Activities (Portuguese: Grupo de Organização da Comissão Nacional de Atividades Espaciais) was formed, operating in São José dos Campos, in the state of São Paulo. Its researchers participated in international projects in the areas of astronomy, geodesy, geomagnetism and meteorology.

The GOCNAE was replaced in April 1971 by the Institute for Space Research, currently called the National Institute for Space Research (INPE). Since the creation of the then Technical Center of Aeronautics (CTA), the current Department of Aerospace Science and Technology (DCTA) of the Brazilian Air Force, in 1946, the country has been following the international progress in the aerospace sector.

With the creation of the Technological Institute of Aeronautics (ITA), a fully qualified institution was formed to train highly qualified human resources in areas of state-of-the-art technology. The DCTA, through the ITA and the Institute of Aeronautics and Space (IAE), play a key role in the consolidation of the Brazilian space program.

In the early 1970s, the Brazilian Space Activities Commission (COBAE) was created - a body linked to the then General Staff of the Armed Forces (EMFA) - to coordinate and monitor the implementation of the space program. This coordinating role, in February 1994, was transferred to the Brazilian Space Agency. The creation of the AEB represents a change in government orientation by establishing a central coordinating body for the space program, reporting directly to the Presidency of the Republic.

In 2011 Argentina's defense minister, Arturo Puricelli, made a proposal to the Brazilian minister, Celso Amorim, for the creation of a unified South American space agency by the year 2025, according to the European Space Agency.[9][10] In 2015, however, the Brazilian Space Agency and the Ministry of Defense rejected the Argentine proposal "because it understood that it would be an organ that would yield a lot of bureaucracy and few results like the 'confederation' proposed by the United States and never came to anything" and also because, according to the agency's adviser, "A regional space agency would reverberate in the Brazilian pocket that, due to its territorial size, would end up getting most of the invoice to pay".[11]

Launch sites

Alcântara Launch Center

The Alcântara Launch Center (Portuguese: Centro de Lançamento de Alcântara; CLA) is the main launch site and operational center of the Brazilian Space Agency.[12] It is located in the peninsula of Alcântara, in the state of Maranhão.[13] This region presents some excellent requirements, such as low population density, excellent security conditions and easiness of aerial and maritime access.[13] The most important factor is its closeness to the Equator - Alcântara is the closest launching base to the Equator.[12] This gives the launch site a significant advantage in launching geosynchronous satellites.[12]

Barreira do Inferno Launch Center

The Barreira do Inferno Launch Center (Portuguese: Centro de Lançamento da Barreira do Inferno; CLBI) is a rocket launch base of the Brazilian Space Agency.[14] It is located in the city of Parnamirim, in the state of Rio Grande do Norte. It is primarily used to launch sounding rockets and to support the Alcântara Launch Center.[15]

Launch vehicles

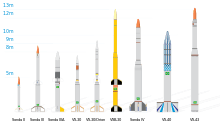

Sounding rockets

The Brazilian Space Agency has operated a series of sounding rockets.

VLM

Brazil has forged a cooperative arrangement with Germany to develop a dedicated micro-satellite launch vehicle. As a result, the VLM "Veiculo Lançador de Microsatelites" (Microsatelite Launch Vehicle) based on the S50 rocket engine is being studied, with the objective of orbiting satellites up to 150 kg in circular orbits ranging from 250 to 700 km. It will be a three-stage rocket, expected to launch the SHEFEX III mission by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in 2019.[16][17][18]

VLS

The VLS - Satellite Launch Vehicle (Portuguese: Veículo Lançador de Satélites) was the Brazilian Space Agency's main satellite launch vehicle.[19] It is a four-stage rocket composed of a core and four strap-on motors.[20] The vehicle's first stage has four solid fuel motors derived from the Sonda sounding rockets.[20] It is intended to deploy 100 to 380 kg satellites into 200 to 1200 km orbit, or to deploy 75 to 275 kg payloads into 200 to 1000 km polar orbit.[20] The first 3 prototypes for the vehicle failed to launch, with the 3rd exploding on the launch pad in 2003 resulting in the deaths of 21 AEB personnel.

The VLS-1 V4 prototype was expected a launch in 2013.[21][22] After subsequent delays, the project was cancelled in 2016.[23]

Southern Cross program

The Brazilian Space Agency was developing a new family of launch vehicles in cooperation with the Russian Federal Space Agency.[24][25][26] The five rockets of the Southern Cross family will be based on Russia's Angara vehicle and liquid-propellant engines.[24]

The first stage of the VLS Gama, Delta and Epsilon rockets was to be powered by a unit based on the RD-191 engine.[24] The second stage, which will be the same for all the Southern Cross rockets, will be driven by an engine based on the Molniya rocket.[24] The third stage will be a solid-propellant booster based on an upgraded version of the VLS-1.[24] The program was named "Southern Cross" in reference to the Crux constellation, present on the flag of Brazil and composed of five stars.[27] Hence the names of the future launch vehicles:[27]

- VLS Alfa (light-weight rocket)

The first rocket to be developed. As a direct modification of the VLS-1 of the original project, replacing the fourth and fifth stages by a single liquid fuel engine. It can place payloads in the range 200–400 kg in orbits up to 750 km.

- VLS Beta (light-weight rocket)

Consisting of three stages without auxiliary thrusters. The first stage is a solid fuel propellant 40 tons, the second will have 30 tons of thrust engine and the latter will be 7.5 tons of thrust, with the same mixture "Kerolox". It can place payloads up to 800 kg in orbits up to 800 km.

- VLS Gama (light-weight rocket)

The VLS Gama launcher is part of the light-weight class, but using the near-equatorial position of the Alcântara Launch Center, it can place almost 1 ton of payload into orbit up to 800 km.

- VLS Delta (medium-weight rocket)

The VLS Delta launcher is a medium-weight rocket and differs from the Gamma by having four solid-propellant boosters attached to the first stage.[24] Its payload deliverable to a geostationary orbit is 2 tons.[24]

- VLS Epsilon (heavy-weight rocket)

The VLS Epsilon launcher is a heavy-weight rocket with three identical units attached to the first stage.[24] It can place a 4 tons spacecraft in geostationary orbit, if it is launched from Alcântara.[24]

The Brazilian government was planning to allocate $1 billion dollars for the project over six years.[24] It has already set aside $650 million for the construction of five launch pads able to handle up to 12 launches per year.[24] The program was scheduled to be completed by 2022.[27] However, it was cancelled by Brazilian President Dilma Rouseff. Instead, Brazil will focus on a series of smaller launch vehicles that appear to rely more on home-grown technology.

Engines

A number of different engines[28] were developed for usage on the several launch vehicles:

- S-10-1 solid rocket engine.[29] Used on Sonda 1. Thrust: 27 kN.

- S-10-2 solid rocket engine.[30] Used on Sonda 1. Thrust: 4.20 kN, burn time: 32 s.

- S-20 Avibras solid rocket engine.[31] Used on Sonda 2 and Sonda 3. Thrust:36 kN

- S-23 Avibrassolid rocket engine.[32] Used on Sonda 3M1. Thrust:18 kN

- S-30 IAE solid rocket engine.[33] Used on Sonda 3, Sonda 3M1, Sonda 4, VS-30, VS-30/Orion and VSB-30. Thrust: 20.490 kN

- S-31 IAE solid rocket engine.[34] Used on VSB-30. Thrust: 240 kN

- S-40TM IAE solid rocket engine.[35] Used on VLS-R1, VS-40, VLS-1 and VLM-1. Thrust: 208.4 kN, isp=272s.

- S-43 IAE solid rocket engine.[36] Used on Sonda 4, VLS-R1 and VLS-1. Thrust: 303 kN, isp=265s

- S-43TM IAE solid rocket engine.[37] Used on VLS-R1, VLS-1 and VLM. Thrust: 321.7 kN, isp=276s

- S-44 IAE solid rocket engine.[38] Used on VLS-R1, VS-40, VLS-1 and VLM-1. Thrust:33.24 kN, isp=282s

- L5 (Estágio Líquido Propulsivo (EPL)) liquid fuel rocket engine. Tested on VS-30 and projected for use on VLS-Alfa.[39]

- L15 liquid fuel rocket engine. Projected for use on VS-15.[40] Thrust: 15 kN

- L75 liquid fuel rocket engine, similar to the Russian RD-0109.[41] Projected for use on VLS-Alfa, VLS-Beta, VLS-Omega, VLS-Gama and VLS-Epsilon. Thrust: 75 kN

- S-50 IAE solid rocket engine. Projected for use on VLM-1 and VS-50.[39][42]

- L1500 liquid fuel rocket engine.[41] Used on VLS-Beta, VLS-Omega, VLS-Gama and VLS-Epsilon. Thrust: 1500 kN

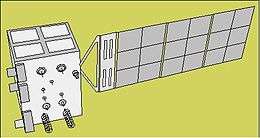

Satellites

The Brazilian Space Agency has several active imagery intelligence satellites in orbit, including reconnaissance and earth observation satellites. Several others are currently in development.

| Satellite | Origin | Type | Operational | Status |

| SCD1[43] | Earth observation | 1993- | Active | |

| SCD2[43] | Earth observation | 1998- | Active | |

| CBERS-1[44] | Earth observation | 1999-2003 | Retired | |

| CBERS-2[45] | Earth observation | 2003-2007 | Retired | |

| CBERS-2B[44] | Reconnaissance | 2007-2010 | Retired | |

| CBERS-3 | Earth observation | 2013 | Launch failure | |

| CBERS-4 | Earth observation | 2014- | Active | |

| SGDC-1 | Communications satellite | 2016 | Active | |

| Amazônia-1 | PMM - "Plataforma Multimissão" (Multi-mission Platform) | 2018 | Planned | |

| Flora Hiperspectral | PMM - "Plataforma Multimissão" (Multi-mission Platform) | 2018+ | Planned | |

| CBERS-4B | Earth observation | 2019 | Planned | |

| LATTES-1 | Space weather (EQUARS) and X-ray space telescope (MIRAX) mission | 2018+ | Planned | |

| SABIA-Mar-1 | PMM - "Plataforma Multimissão" (Multi-mission Platform) | 2020 | Planned | |

| CLE-1 | Low earth orbit | 2018 | Planned | |

| Amazônia-1B | PMM - "Plataforma Multimissão" (Multi-mission Platform) | 2018 | Planned | |

| GEOMET-1 | Earth observation | 2018 | Planned | |

| AST-1 | Low earth orbit | 2019 | Planned | |

| SABIA-Mar-1B | PMM - "Plataforma Multimissão" (Multi-mission Platform) | 2019 | Planned | |

| SGDC-2 | Communications satellite | 2019 | Planned | |

| Amazônia-2 | PMM - "Plataforma Multimissão" (Multi-mission Platform) | 2020 | Planned | |

| SAR-1 | Earth observation | 2020 | Planned | |

| AST-2 | Low earth orbit | 2020 | Planned | |

Human spaceflight

Marcos Pontes, a lieutenant colonel in the Brazilian Air Force, is an astronaut of the Brazilian Space Agency.[47] Pontes was the first Brazilian astronaut,[48] having launched with the Expedition 13 crew from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on March 29, 2006 aboard a Soyuz-TMA spacecraft.[49] Pontes docked with the International Space Station (ISS) on March 31, 2006, where he lived and worked for 9 days.[48] Pontes returned to Earth with the Expedition 12 crew, landing in Kazakhstan on April 8, 2006.[48] In January 2019,Pontes was nominated by the Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro as Minister of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communication, a position he holds still.

| Name | Position | Time in space | Launch date | Mission | Mission insignia | Status | |

| Marcos Pontes | Mission Specialist | 9d 21h 17m | March 30, 2006 | Soyuz TMA-8 Missão Centenário Soyuz TMA-7 | Active, on stand-by | |

International cooperation

China/CBERS

The China–Brazil Earth Resources Satellite program (CBERS) is a technological cooperation program between Brazil and China which develops and operates Earth observation satellites. Brazil and China negotiated the CBERS project during two years (1986–1988), renewed in 1994 and again in 2004.

International Space Station

The Brazilian Space Agency is a bilateral partner of NASA in the International Space Station.[50] The agreement for the design, development, operation and use of Brazilian developed flight equipment and payloads for the Space Station was signed in 1997.[50] It includes the development of six items, among which are a Window Observational Research Facility and a Technology Experiment Facility.[47] In return, NASA will provide Brazil with access to its ISS facilities on-orbit, as well as a flight opportunity for one Brazilian astronaut during the course of the ISS program.[50] However, due to cost issues, the subcontractor Embraer was unable to provide the promised ExPrESS pallet, and Brazil left the programme in 2007.[51][52] However, as a compromise, NASA have funded small Brazilian-made components for the Express Logistics Carrier-2 for the ISS, which were installed in 2009.[53]

Ukraine/Ciclone 4

On October 21, 2003, the Brazilian Space Agency and the State Space Agency of Ukraine established a cooperation agreement creating a joint venture space enterprise called Alcântara Cyclone Space.[54] The new company will focus on launching satellites from the Alcântara Launch Center using the Tsyklon-4 rocket.[55] The company will invest $160 million dollars in infrastructure for the new launch pad that will be constructed at the Alcântara Launch Center.

In March 2009, the Brazilian Government increased its financial capital by US$ 50 million.[56]

The first launch was planned for 2014 from the Alcantara Launch Center.[57]

Japan

On November 8, 2010, National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) signed a Letter of Intent regarding the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD+) program.[58] Examples of the cooperation include the monitoring of illegal logging in the Amazon rainforest utilizing data from JAXA's ALOS satellite. Both Brazil and Japan are members of the Global Precipitation Measurement project.[59]

See also

- National Institute for Space Research (INPE)

- Aerospace Technology and Science Department (DCTA)

- Technological Institute of Aeronautics (ITA)

- List of government space agencies

References

- Presidency of Brazil: Law 8.854 "That creates the Brazilian Space Agency, and other measures" Presidency of Brazil. Retrieved on 2009-07-30. (in Portuguese)

- The President of the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB) visited the Centre. Regional Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in Asia and the Pacific. 24 May 2014.

- http://www.aeb.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Relat%C3%B3rio-de-Gest%C3%A3o-2018_AEB.pdf

- Brazilian Space Agency Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine The Internet Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved on 2009-07-29.

- BBC World: Brazil Launches rocket into space BBC News. Retrieved on 2009-07-30.

- Space.com: Brazil completes successful rocket launch Archived 2008-07-24 at the Wayback Machine Space.com. Retrieved on 2009-07-30.

- Herald Tribune: Brazil launches rocket for gravity research International Herald Tribune. Retrieved on 2009-07-30.

- BBC World: First Brazilian goes into space BBC News. Retrieved on 2009-07-30.

- "Argentina propõe ao Brasil criação de agência espacial sul-americana - Ciência - iG". Último Segundo. Aug 30, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- "Ministros do Brasil e Argentina apoiam cooperação". VEJA. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- "DefesaNet - Especial Espaço - AEB recua e extingue criação da Agência Espacial Latino Americana". www.defesanet.com.br. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Centros de Lançamentos: CLA Archived July 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Brazilian Space Agency. Retrieved on 2009-07-30. (in Portuguese)

- Alcantara Launch Center (2°20'S; 44°24'W) GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved on 2009-07-30.

- Barreira do Inferno Launch Center GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved on 2009-07-30.

- Centro de Lançamento da Barreira do Inferno Archived July 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Brazilian Space Agency. Retrieved on 2009-07-30. (in Portuguese)

- Brazilian space plans: 2011-2015 nasaspaceflight.com. Retrieved on 2012-03-06.

- "Brazilian Space". Brazilianspace.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- "VLM: veículo lançador de microsatélites, launch vehicle for SHEFEX-3". German Aerospace Center (DLR). Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- Veículos Lançadores: VLS Archived 2009-07-12 at the Wayback Machine Brazilian Space Agency. Retrieved on 2009-07-29. (in Portuguese)

- VLS (Brazilian rocket) The Internet Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved on 2009-07-29.

- Saiba como está o projeto Veículo Lançador de Satélite (VLS) Brazilian Air Force. Retrieved on 2012-03-06. (in Portuguese).

- "Brazil: IAE Conducts VLS Qualification Tests at Parabolic Arc". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- http://jornaldosindct.sindct.org.br/index.php?q=node/615 Archived 2016-08-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Russia Begins Elbowing Ukraine Out From Brazil's Space Program SpaceDaily.com. Retrieved on 2009-07-29.

- Brasil e Rússia, juntos em órbita e na exploração espacial Archived January 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Estadão. Retrieved on 2009-07-29. (in Portuguese)

- Programa Cruzeiro do Sul Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine DefesaBR. Retrieved on 2009-07-29. (in Portuguese)

- Programa de Veículos Lançadoeres de Satélites Cruzeiro do Sul Brazilian General Command for Aerospace Technology. Retrieved on 2009-07-29. (in Portuguese)

- "Brazil". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-10-1". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-10-2". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-20". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-23". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-30". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-31". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-40TM". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-43". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-43TM". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "S-44". Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- http://www.aeb.gov.br/download/revista/RevistaAEB_n13.pdf%5B%5D

- Brazilian Space. "BRAZILIAN SPACE". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- http://www.ecsbdefesa.com.br/defesa/fts/TPLB.pdf

- Brazilian Space. "BRAZILIAN SPACE". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Satélite de Coleta de Dados - SCD GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved on 2011-01-17.

- The Launch of CBERS-2B Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine National Institute for Space Research. Retrieved on 2011-01-17.

- Overview of the CBERS-2 Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine United States Geological Survey. Retrieved on 2011-01-17.

- http://www.inpe.br/noticias/arquivos/pdf/Plano_diretor_miolo.pdf

- AEB: Human Spaceflight GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved on 2011-01-17.

- Astronaut Bio: Marcos C. Pontes. Archived 2017-04-17 at the Wayback Machine NASA. Retrieved on 2011-01-17.

- Rohter, Larry (Apr 8, 2006). "Brazil's Man in Space: A Mere 'Hitchhiker,' or a Hero?". Retrieved May 7, 2020 – via NYTimes.com.

- NASA Signs International Space Station Agreement With Brazil NASA. Retrieved on 2011-01-17.

- Emerson Kimura (2009). "Made in Brazil O Brasil na Estação Espacial Internacional" (in Portuguese). Gizmodo Brazil. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- "G1 > Brasil - NOTÍCIAS - Brasil está fora do projeto da Estação Espacial (ISS)". g1.globo.com. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- "ISS Assembly: EXPRESS Pallet". spaceflight.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- Ucrânia Archived 2016-01-17 at the Wayback Machine Defesa BR. Retrieved on 2009-07-29. (in Portuguese)

- Brazil-Ukraine joint venture space company eyes global satellite launch market; to start operations this year GIS News. Retrieved on 2009-07-29.

- Autoriza o aumento de capital social da Empresa Binacional Alcântara Cyclone Space Presidency of Brazil. Retrieved on 2009-07-29. (in Portuguese)

- "Brazil Scales Back Launch Vehicle Plans – Parabolic Arc". Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- "JAXA and INPE Signing Letter of Intention in cooperation for REDD+ using DAICHI" (Press release). JAXA. November 8, 2010. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- BRAZILIAN PARTICIPANTS IN GPM GPM-Br 2010. Retrieved on 2015-08-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brazilian Space Agency. |