Manned Orbiting Laboratory

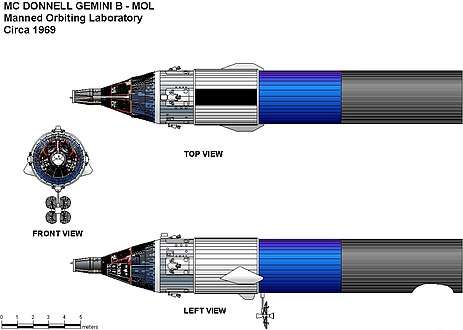

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) was part of the United States Air Force's human spaceflight program. The project was developed from early United States Air Force (USAF) concepts of crewed space stations to be used for satellite reconnaissance purposes, and was a successor to the canceled Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar military reconnaissance space plane. MOL evolved into a single-use laboratory, for which crews would be launched on 40-day missions, and return to Earth using a Gemini B spacecraft derived from NASA's Gemini spacecraft.

A 1967 conceptual drawing of the Gemini B reentry capsule separating from the MOL at the end of a mission | |

| Station statistics | |

|---|---|

| Crew | 2 |

| Mission status | Canceled |

| Mass | 14,476 kg (31,914 lb) |

| Length | 21.92 m (71.9 ft) |

| Diameter | 3.05 m (10.0 ft) |

| Pressurized volume | 11.3 m3 (399.1 cu ft) |

| Orbital inclination | polar orbit |

| Days in orbit | 40 days |

| Configuration | |

Configuration of the Manned Orbital Laboratory | |

The MOL program was announced to the public on 10 December 1963 as an inhabited platform to prove the utility of putting people in space for military missions. Astronauts selected for the program were later told of the secret reconnaissance mission. The prime contractor for the spacecraft was McDonnell Aircraft; the laboratory was built by the Douglas Aircraft Company. The Gemini B was externally similar to NASA's Gemini spacecraft, although it underwent several modifications, including the addition of a circular hatch through the heat shield, which allowed passage between the spacecraft and the laboratory. Vandenberg Air Force Base Space Launch Complex 6 was developed to permit launches into polar orbit.

As the 1960s went on, the MOL competed with the Vietnam War for funds, and resultant budget cuts repeatedly caused postponement of the first operational flight. At the same time, automated systems rapidly improved, narrowing the benefits of a crewed space platform over an automated one. A single uncrewed test flight of the Gemini B spacecraft was conducted on 3 November 1966, but MOL was canceled in June 1969.

The Titan IIIM rocket developed for the MOL never flew, but its UA1207 solid rocket boosters were used on the Titan IV, and the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster was based on materials, processes and designs developed for them, with only minor changes. NASA space suits were derived from the MOL ones, MOL's waste management system flew in space on Skylab, and NASA Earth Science used other MOL equipment.

Background

At the height of the Cold War in the mid-1950s, the United States Air Force (USAF) was particularly interested in reconnaissance from space, as there was intense interest in the Soviet Union's military and industrial capabilities. In July 1957—before anyone had flown in space—the USAF Wright Air Development Center had published a paper the employment of space vehicles that considered the development of a space station equipped with telescopes and other observation devices.[1] The USAF already started a satellite program in 1956 called WS-117L. It had three components: SAMOS, a spy satellite; Discoverer, an experimental program to develop the technology; and MIDAS, an early warning system.[2]

.jpg)

Starting in 1956, the United States had conducted covert U-2 spy plane overflights of the Soviet Union. Twenty-four U-2 missions produced images of about 15 percent of the country with a maximum resolution of 2 feet (0.61 m) before the downing of a U-2 in 1960 abruptly ended the program.[3] This left a gap in American espionage capabilities that it was hoped that spy satellites would be able to fill.[4] The launch of Sputnik 1, the first satellite, by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957, came as a profound shock to the American public, which had complacently assumed American technical superiority.[5][6]

One benefit of the Sputnik crisis to American space policy was that no government protested Sputnik's overflying their territory, thereby tacitly acknowledging the legality of satellites. While there was a big difference between the innocuous Sputnik and a spy satellite, it made it all that much harder for the Soviets to object to one.[7] In February 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the USAF to proceed as quickly as possible with Discover (also known as Corona) as a joint Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)-USAF interim project.[8][9]

On 18 August 1958, Eisenhower decided to give responsibility for most forms of human space flight to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Deputy Secretary of Defense Donald A. Quarles transferred $53.8 million (equivalent to $367 million in 2018) that had been set aside for USAF space projects to NASA.[10] This left the USAF with a small number of programs with a direct military impact.[11] One was a delta-wing, rocket-propelled glider that came to be called the Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar.[12] The USAF remained interested in space, and March 1959, the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force, General Thomas D. White asked the USAF Director of Development Planning to prepare a long-range plan for a USAF space program. One project identified in the resulting document was a "manned orbital laboratory".[13]

The USAF Air Research and Development Command (ARDC) issued a request to the Aeronautical Systems Division (ASD) at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base on 1 September 1959 for a formal study to be conducted of a military test space station (MTSS). The ASD asked components of the ARDC for suggestions as to what sort of experiments would be suitable for an MTSS, and 125 proposals were received. Twelve contractors made proposals. A request for proposal (RFP) was then issued on 19 February 1960, and twelve firms responded. On 15 August, General Electric, Lockheed Aircraft, Martin, McDonnell Aircraft, and General Dynamics were awarded $574,999 (equivalent to $3.78 million in 2018) for a study of the MTSS.[13] Their preliminary reports were submitted in January 1961, and final reports were received by July. With these in hand, on 16 August 1961 the USAF submitted a request for $5 million (equivalent to $32.8 million in 2018) in funding for space station studies in fiscal year 1963, but no funding was forthcoming.[14]

In its 26 April 1961 project plan, Dyna-Soar was to be launched into space on a suborbital ballistic trajectory by a Titan I booster, with its first piloted suborbital flight in April 1965, followed by its first piloted orbital flight in April 1966,[15][16] In a 22 February memorandum to the Secretary of the Air Force, Eugene Zuckert, the Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, decided to fast track Dyna-Soar and save money by skipping the suborbital testing phase. Dyna-Soar would be launched into orbit by a Titan III booster.[14][17][18]

The same 22 February memorandum gave tacit approval for the development of a space station. With this in hand, the USAF staff and the Air Force Systems Command (AFSC) began planning for a space station, which was now known as a military orbital development system (MODS). By the end of May, a proposed system package plan (PSPP) had been drawn up for MODS. For tracking purposes, it was given the numerical designation Program 287. MODS consisted of a space station, a modified NASA Gemini spacecraft that became known as Blue Gemini, and a Titan III launch vehicle. The space station was expected to provide a shirt-sleeve environment for a crew of four for up to 30 days.[14] On 25 August 1962, Zuckert informed General Bernard Adolph Schriever, the commander of the AFSC, that he was to proceed with studies of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) as the director of the program.[19][20]

On 9 November 1962, Zuckert submitted his proposals to McNamara. For fiscal year 1964, he requested $75 million (equivalent to $486 million in 2018) in funding for MODS and $102 million (equivalent to $670 million in 2018) for Blue Gemini.[19] This involved some negotiation with NASA, but McNamara and NASA Administrator reached an agreement on cooperation on Project Gemini on 21 January 1963.[21]

McNamara called for a review of Dyna-Soar, specifically whether it had a military capability that could not be met by Gemini, on 18 January 1963. In his 14 November response, the Director of Defense Research and Engineering (DDR&E), Harold Brown, examined various options for a space station. He preferred a four-man station that would be launched separately and crewed by astronauts arriving in Gemini spacecraft. Crews would rotate every 30 days, with resupply arriving every 120 days.[22][23] On 10 December 1963, McNamara issued a press release that officially announced the cancellation of Dyna-Soar, and the initiation the MOL program.[24]

Soon after coming to office, the Kennedy administration tightened security regarding spy satellites in response to Soviet sensitivities.[25] No administration official could even admit they existed until President Jimmy Carter did so in 1978.[26] MOL therefore became a semi-secret project, with a public face but a covert reconnaissance mission, similar to that of the Discoverer/Corona spy satellite program.[27]

Planning

On 16 December 1963, USAF Headquarters ordered Schriever to submit a development plan for the MOL.[28] About $6 million (equivalent to $37.9 million in 2018) was spent on preliminary studies, most of which were completed by September 1964. McDonnell prepared a study of the Gemini B spacecraft, Martin Marietta of the Titan III booster,[29] and Eastman Kodak of camera optics.[25] Other studies examined key MOL subsystems such as environmental control, electrical power, navigation, attitude control stabilization, guidance, communications, and radar.[30]

The United States Under Secretary of the Air Force and the Director of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), Brockway McMillan, asked the NRO Program A Director (responsible for the Air Force aspects of NRO activities), Major General Robert Evans Greer, to look into its potential reconnaissance capabilities.[29] In all, $3,237,716 (equivalent to $20.4 million in 2018) was expended on these studies. The most expensive was of the Gemini B spacecraft, which cost $1,189,500 (equivalent to $7.51 million in 2018), followed by the Titan III interface, which cost $910,000 (equivalent to $5.75 million in 2018).[30]

With these studies in hand, the USAF issued an RFP to twenty firms in January 1965. At the end of February, Boeing, Douglas, General Electric and Lockheed were selected to carry out design studies.[29] Covert NRO activities to be carried out by MOL were classified secret and given the code name "Dorian".[31] In February 1969 the MOL was given a Key Hole designation as KH-10 Dorian.[32]

As a black project (i.e. one that secret and publicly unacknowledged), but one that was impossible to completely conceal, MOL needed some "white" (i.e. unclassified and publicly acknowledged) experiments as cover. An MOL Experiments Working Group was created under Colonel William Brady. Some 400 experiments proposed by various agencies were examined. These were consolidated and reduced to 59, and twelve primary and eighteen secondary ones were selected. A 499-page report on the experiments was issued on 1 April 1964.[33] Although reconnaissance was its main purpose, "manned orbiting laboratory" was an accurate description; the program hoped to prove that soldiers could perform militarily useful tasks in a shirt-sleeve environment in space for 30 days.[34]

The USAF recommended that the MOL use the Gemini B spacecraft with the Titan III booster. A program of six flights (one uncrewed and five crewed) was proposed, with the first flight taking place in 1966.[35] The program was costed at $1.653 billion (equivalent to $10.4 billion in 2018). The Science Advisor to the President, Donald Hornig, reviewed the USAF's submission. He noted that for the sophisticated reconnaissance missions proposed, a human-operated system was far superior to an automated one, but speculated that with sufficient effort, the gap between the two could be reduced. He also noted that while the notion of satellites passing overhead was accepted, a crewed space station might be a different matter,[36] but the Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, thought that this could be managed.[37]

There remained the question of whether the improved performance compared to the automated KH-8 Gambit 3 satellite then under development justified the cost. The Director of Central Intelligence, Admiral William Raborn agreed that it might. McNamara took the proposal to President Lyndon Johnson on 24 August 1965, who approved it, and issued an official announcement at a press conference the following day.[36][38]

In January 1965, Schriever had appointed Brigadier General Harry L. Evans as his deputy for MOL. Evans had previously worked with Schriever in the USAF Ballistic Systems Division.[39] He had been the Discover/Corona program manager, and had supervised SAMOS, MIDAS and SAINT, together with the early communications and weather satellite programs.[40][41] In addition to being Schriever's deputy, Evans became Zuckert's Special Assistant for MOL on 18 January 1965. In this role, he reported directly to Zuckert, and was responsible for liaison between MOL and other agencies such as NASA.[39]

In the wake of the President's announcement of the program, MOL was given the designation Program 632A, and the USAF announced the appointment of Schriever as MOL director and Evans as vice director, in charge of the MOL staff at The Pentagon, with Brigadier General Russell A. Berg as deputy director, in charge of the MOL staff at the Los Angeles Air Force Station in El Segundo, California.[42] The MOL System Program Office (SPO) was created in March 1964 under Brigadier General Joseph S. Bleymaier, the Deputy Commander of the AFSC Space Systems Division (SSD). By August 1965, the MOL had a staff of 42 military and 23 civilian personnel.[43] Schriever retired in August 1966, and was succeeded as head of the AFSC and MOL Program Director by Major General James Ferguson.[44] Evans retired on 27 March 1968, and was replaced by Major General James T. Stewart.[45]

Schriever and the Director of the NRO, Alexander H. Flax, signed a formal agreement covering MOL Black Financial Procedures on 4 November 1965. Under this agreement, the Deputy Director MOL would forward black budget cost estimates to the NRO Controller, who had the authority to obligate NRO funds. This was followed by a corresponding MOL White Financial Procedures Agreement, which was approved by Flax in December and signed by Leonard Marks Jr., the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (Financial Management & Comptroller). This provided for a more regular channel, with funds going through the AFSC to its Space Systems Division (SSD) and thence to the MOL SPO. Thus far no definition contracts had been let, except for the Titan III booster. On 30 September, Brown released $12 million (equivalent to $75.8 million in 2018) in fiscal year 1965 funds and $50 million (equivalent to $316 million in 2018) in fiscal year 1966 funds for the MOL definition phase activities.[46]

The President had announced two contractors: Douglas and General Electric. While the former had considerable technical and managerial experience from the Thor, Genie and Nike projects, General Electric had experience with large optical systems, and, perhaps more importantly, had over 1,000 personnel immediately cleared for Dorian, while Douglas had very few. A $10.55 million (equivalent to $63.6 million in 2018) Fixed-price contract was signed with Douglas on 17 October. Contract negotiations with General Electric were also completed around this time, and it was given $4.922 million (equivalent to $29.7 million in 2018), all but $0.975 million (equivalent to $5.88 million in 2018) of it in black funds.[46]

The Aerospace Corporation was given responsibility for general systems engineering/technical direction.[47] Douglas selected five major subcontractors: Hamilton-Standard for environmental control and life support; Collins Radio for the communications; Honeywell for the attitude control; and Pratt & Whitney for the electrical power; and IBM for data management. Aerospace and the MOL SPO concurred with all but the last, noting that while IBM had a technically superior bid to Univac, its estimated cost was $32 million (equivalent to $193 million in 2018) compared to Univac's $16.8 million (equivalent to $101 million in 2018). Douglas decided to let study contracts to both firms.[46]

As of 1 September 1966, the MOL flight schedule was:

- 15 April 1969 – MOL 1 – First Titan IIIM qualification flight (simulated Orbiting Vehicle) [48][49]

- 1 July 1969 – MOL 2 – Second uncrewed Gemini-B/Titan 3M qualification flight (Gemini-B flown alone, without an active laboratory) [48][49]

- 15 December 1969 – MOL 3 – A crew of two, commanded by James M. Taylor (possibly with Albert H. Crews) would have spent thirty days in orbit.[48][49][50]

- 15 April 1970 – MOL 4 – Second crewed mission [48][49][51]

- 15 July 1970 – MOL 5 – Third crewed mission [48][49][52]

- 15 October 1970 – MOL 6 – Fourth crewed MOL mission. 30 to 60 days. All-Navy crew composed of Truly and Crippen or Overmyer [48][49][53][54]

- 15 January 1971 – MOL 7 – Fifth crewed MOL [48][49][55]

Modules

Laboratory module

The laboratory module was 5.8-metre (19 ft) high and 3.05-metre (10.0 ft) in diameter. The 0.81-metre (2.7 ft) crew tunnel in the Gemini B heat shield connected it to the spacecraft. The transfer tunnel was surrounded by the cryogenic hydrogen, helium and oxygen storage tanks. This section also housed the environmental control system, the fuel cells, and the four quad reaction control system thrusters and their propellant tanks. The laboratory module was divided into two sections, but there was no division between the two, and the crew could move freely between them.[56]

They were both octagonal in shape, with eight bays: Bays 1 and 8 contained storage compartments; Bay 2, the environmental control system; Bay 3, the hygiene/waste compartment; Bay 4, the biochemical test console and work station; Bays 5 and 6, the airlock; and Bay 7, a glovebox for handling liquids; below that a secondary food console. In the "lower" (as it would have been on the launch pad), Bay 1 contained a motion chair that measured the mass of the crew; Bay 2, two performance test panels; Bay 3, the environmental control system controls; Bay 4, a physiology test console; Bay 5, an exercise device; Bay 6, two emergency oxygen masks; Bay 7, a view port and instrument panel; and Bay 8, the main spacecraft control station.[56]

From its regular 80-nautical-mile (150 km) orbit, the main Dorian camera had a circular field of view 9,000 feet (2,700 m) across. At top magnification it was more like 4,200 feet (1,300 m). This was much smaller than many of targets that the NRO was interested in, such as air bases, shipyards and missile ranges, so the astronauts would have limited time to respond as the MOL passed over them. The astronauts would search for targets using the tracking and acquisition telescopes, which had a circular view of the landscape about 6.5 nautical miles (12.0 km) across, with a resolution of about 30 feet (9.1 m). The main camera would focus on the most important targets, providing a very high resolution image. The aim was to have the most interesting part of the target in the center of the image; due to the optics used, the image was not as sharp around the edges of the frame.[57]

While surveillance targets were preprogrammed and the system could operate automatically, astronauts could decide target priority for filming. By avoiding cloudy areas and identifying more interesting subjects (an open missile silo instead of a closed one, for example), they would save film,[58] the major limitation, since it had to be returned in the small Gemini B spacecraft. In cloudy areas like Moscow, it was estimated that the MOL would be 45 percent more efficient than an automated satellite system, but for sunnier areas like around the Tyuratam missile complex, this might only be 15 percent. Nonetheless, Tyuratam was the sort of target that MOL was intended for. Of 159 KH-7 Gambit photographs of the area, only 9 percent showed missiles on the launch pads, and of 77 photographs of missile silos, only 21 percent were with the doors open. The analysts identified 60 MOL targets in the complex. Only two or three could be photographed on each pass, but the astronauts could select the most interesting ones on the spur of the moment, and photograph them with greater resolution than Gambit. It was hoped that valuable technical information would thereby be obtained.[57]

Specifications

- Crew: 2

- Maximum duration: 40 days

- Orbit: Polar

- Length: 21.92 m (71.9 ft)

- Diameter: 3.05 m (10.0 ft)

- Habitable volume: 11.3 m3 (400 cu ft)

- Gross mass: 14,476 kg (31,914 lb)

- Payload: 2,700 kg (6,000 lb)

- Power: fuel cells or solar cells

- Reaction control system: N

2O

4/MMH - Reference:[53]

Gallery

MOL main features

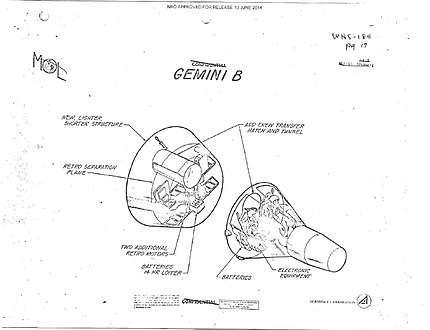

MOL main features Gemini B layout

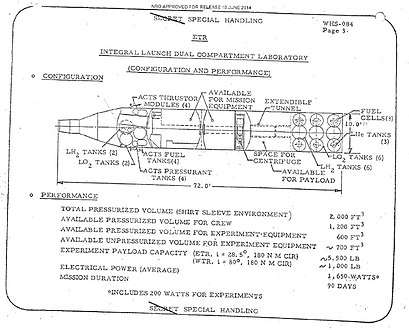

Gemini B layout Integral launch dual compartment laboratory

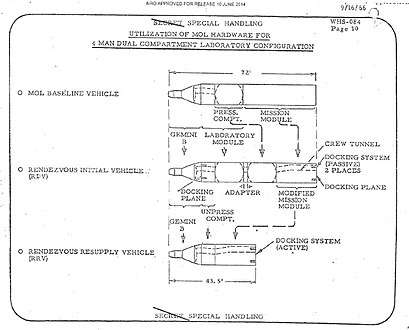

Integral launch dual compartment laboratory MOL variations

MOL variations

Future plans

The MOL program expected that Block II of the space station, to start in July 1974, would add image transmission and geodetic system targeting. Astronauts would perform infared, multispectral, and ultraviolet astronomy when they had time during an extended mission duration on twice-annual flights.[59] After Block II, the program hoped to use MOL to build larger, permanent facilities. A planning document depicted 12-man and 40-man stations, both with self-defense capability. It described the 40-man, Y-shaped station as a "spaceborne command post" in synchronous orbit. With the "key requirement - post attack survivability", the station would be capable of "Strategic/tactical decision making" during a global war.[60][59]

Spacecraft

The Gemini capsule was redesigned for the MOL and named Gemini B. It would be launched together with the MOL modules. Once in orbit, the crew would power down the capsule and activate and enter the laboratory module. After about one month of space station operations, the crew would return to the Gemini B capsule, power it up, separate from the station, and perform reentry. Gemini B had an autonomy of about 14 hours once detached from MOL.[61][62][63]

Externally Gemini B was similar to Gemini, but there were many differences. The most noticeable was that it featured a rear hatch for the crew to enter MOL. Notches were cut into the ejection seat headrests to allow access to hatch. The seats were therefore a mirror image of each other instead of being the same. Gemini B also had a larger diameter heat shield to handle higher energy reentry from polar orbit. The number of reentry control system thrusters was increased from four to six. There was no orbit attitude and maneuvering system (OAMS), because capsule orientation for reentry was handled by the forward reentry control system thrusters, and the laboratory module had its own reaction control system for orientation.[61][62][63]

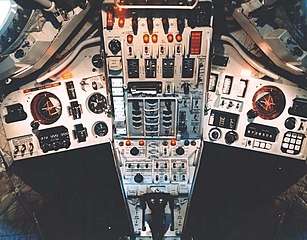

The Gemini B systems were designed for long term orbital storage (40 days) but equipment for long duration flights was removed since Gemini B capsule itself was only to be used for launch and reentry. It had a different cockpit layout and instruments. As a result of the Apollo 1 fire, the MOL was switched to use a helium-oxygen atmosphere instead of pure oxygen one. At takeoff, the astronauts would breathe pure oxygen in their spacesuits while the cabin was presurized with helium. It would then be brought up to a helium-oxygen mix.[61][62][63] This was an option that had been provided for in the original design.[64]

Reentry module specifications

- Crew: 2

- Maximum duration: 40 days

- Length: 3.35 m (11.0 ft)

- Diameter: 2.32 m (7 ft 7 in)

- Cabin volume: 2.55 m3 (90 cu ft)

- Gross mass: 1,983 kg (4,372 lb)

- RCS thrusters: 16 N × 98 N (3.6 lbf × 22.0 lbf)

- RCS impulse: 283 seconds (2.78 km/s)

- Electric system: 4 kWh (14 MJ)

- Battery: 180 A·h (648,000 C)

- Source:[62]

Gallery

Flown Gemini B prototype

Flown Gemini B prototype Heat shield with hatch

Heat shield with hatch Display panel

Display panel Gemini B nose

Gemini B nose Control panel

Control panel Spacecraft interior

Spacecraft interior

Spacesuits

The MOL program's requirements for a spacesuit were a product of the spacecraft design. The Gemini capsule had little room inside, and the MOL astronauts gained access to the laboratory through a hatch in the heat shield. This required a more flexible suit than those of NASA astronauts. The NASA astronauts had custom-made set of flight, training and backup suits, but for the MOL the intention was that spacesuits would be provided in standard sizes with adjustable elements. The USAF sounded out the David Clark Company, International Latex Corporation, B. F. Goodrich and Hamilton Standard in 1964. Hamilton Standard and David Clark each developed four prototype suits for the MOL.[65] A competition was held at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in January 1967, and a production contract awarded to Hamilton Standard. At least 17 blue MOL MH-7 training suits were delivered between May 1968 and July 1969. A single MH-8 flight configuration suit was delivered in October 1968 for certification testing. The flight suit was intended to be worn during launch and reentry.[66]

The contract for the launch/reentry suit was followed by a second competition in September 1967 for a suit for extravehicular activity (EVA).[67] This too was won by Hamilton Standard. The design was complicated by USAF concerns that a crew member might slip their tethers and float away. As a result, an astronaut maneuvering unit (AMU) was developed and integrated with the life support system as an integrated maneuvering and life support system (IMLSS). The design was completed by October 1968, and a full prototype with cover garments was delivered in March 1969. The cover garments were never completed.[67]

Astronauts

Selection

To provide prospective astronauts for the X-15 rocket-powered aircraft, Dyna-Soar and MOL programs, the USAF created the Aerospace Research Pilot Course at the USAF Experimental Flight Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Four classes were conducted between June 1961, and May 1963. The third class received instruction on Dyna-Soar as part of the course. The USAF Experimental Test Pilot School was renamed the Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS) on 12 October 1961.[68][69] When it came to selecting astronauts for MOL, the commandant of the ARPS, Schriever took the advice of Colonel Charles E. "Chuck" Yeager, the commandant of the ARPS, and restricted selection to ARPS graduates. The program did not accept applications; 15 candidates were selected and sent to Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, for a week of medical evaluation in October 1964. The evaluations were similar to those conducted for the NASA astronaut groups.[70][71]

For the first three NASA astronaut groups in 1959, 1962, and 1963, the USAF established a selection board to review candidates before forwarding their names to NASA. The Chief of Staff of the USAF, General John P. McConnell, told Schriever he expected the selection of MOL astronauts to follow the same procedure. A selection board was convened in September 1965, chaired by Major General Jerry D. Page. On 15 September, the selection criteria for MOL was announced.[72] Candidates had to be:

- Qualified military pilots;

- Graduates of the ARPS;

- Serving officers, recommended by their commanding officers; and

- Holding US citizenship from birth.[72]

In October 1965, the MOL Policy Committee decided that MOL crew members would be designated a "MOL Aerospace Research Pilots" rather than astronauts.[73]

The names of the first group of eight MOL pilots were announced on 12 November 1965 as a Friday night news dump to avoid press attention. To prevent their return to the Navy, Finley and Truly stayed at ARPS as instructors until the announcement:[74]

- Major Michael J. Adams, USAF

- Major Albert H. Crews Jr., USAF

- Lieutenant John L. Finley, USN

- Captain Richard E. Lawyer, USAF

- Captain Lachlan Macleay, USAF

- Captain Francis G. Neubeck, USAF

- Major James M. Taylor, USAF

- Lieutenant Richard H. Truly, USN.[72]

Around this time, the USAF began selecting a second group of MOL pilots. This time applications were accepted. Selection occurred at the same time as for NASA Astronaut Group 5, with many applying to both programs. Successful candidates were told that NASA or MOL chose them, with no explanation.[75] Over 500 applications were received, from which the names of 100 candidates were forwarded to USAF headquarters. The MOL program Office selected 25, who were sent to Brooks Air Force Base for physical evaluation in January and February 1966. Five were selected. The names of the second group of MOL pilots were publicly announced on 17 June 1966:

- Captain Karol J. Bobko, USAF

- Lieutenant Robert L. Crippen, USN

- Captain C. Gordon Fullerton, USAF

- Captain Henry W. Hartsfield, USAF

- Captain Robert F. Overmyer, USMC.[70][76]

Bobko became the first graduate of the United States Air Force Academy to be selected as an astronaut.[77]

Eight other finalists had not yet completed ARPS. One was already attending; the other seven were sent to Edwards Air Force Base to join Class 66-B. They would be considered for the next MOL astronaut intake. The MOL Astronaut Selection Board met again on 11 May 1967, and recommended that four of the eight be appointed. The MOL Program Office announced names of those selected for the third group of MOL astronauts on 30 June 1967:

- Major James A. Abrahamson, USAF

- Lieutenant Colonel Robert T. Herres, USAF

- Major Robert H. Lawrence Jr., USAF

- Major Donald H. Peterson, USAF.[70][78]

Training

MOL astronauts knew that the program would be a space laboratory for military experiments, but did not learn of its reconnaissance role until after selection; they were advised to resign if they disliked the classified aspect. After receiving security clearances, being introduced to Sensitive Compartmented Information such as Dorian, Gambit, Hexagon, and Talent Keyhole—what Truly described as "two space programs: the public, what the public knew and astronauts and all that jazz, and then this other world of capability that didn’t exist"—amazed the astronauts.[79]

Phase I of crew training was a two-month introduction to the MOL program in the form of a series of briefings from NASA and the contractors. Phase II lasted for five months, and was conducted at the ARPS, where the astronauts were given technical training on the MOL vehicles and their operation procedures. This training was conducted in classrooms, in training flights, and win sessions on the T-27 space flight simulator. Phase III was continuous training on the MOL systems and providing crew input them. The pilots spent most of their time in this phase. Phase IV was training for specific missions. Simulators were developed for each of the different MOL systems. There was a Laboratory Module Simulator, Mission Payload Simulator, and Gemini B Procedures Simulator. Training was conducted in a zero-G environment on a Boeing C-135 Stratolifter reduced-gravity aircraft. A Flotation-Egress trainer allowed the astronauts to prepare for a splashdown and the possibility of the spacecraft sinking.[80]

NASA had pioneered neutral buoyancy simulation as a training aid to simulate the space environment. The pilots were given scuba diving training at the U.S. Navy Underwater Swimmers School in Key West, Florida. Training was then conducted on a General Electric simulator on Buck Island, near St. Thomas in the US Virgin Islands. Water survival training was conducted at the USAF Sea Survival School at Homestead Air Force Base in Florida, and jungle survival training at the Tropical Survival School at Howard Air Force Base in the Panama Canal Zone. In July 1967, the pilots underwent training at the National Photographic Interpretation Center in Washington, DC.[81]

Facilities

Launch complex

The military director of the NRO, Brigadier General John L. Martin suggested that MOL launches be made from Cape Kennedy, as launches from the West Coast would lead to the assumption that the mission was reconnaissance.[25] This was considered, but there were practical issues. MOL needed to be flown in a polar orbit, but a launch due south from Cape Kennedy would overfly southern Florida, which raised safety concerns.[82] The TIROS weather satellites had performed a "dog leg" maneuver, flying east and then south to avoid southern Florida. This required special State Department approval, as it meant overflying Cuba. The loss of a MOL with a classified payload over Cuba would not only be a danger to life and property, but a serious security concern as well. Moreover, the dog leg maneuver would reduce the 30,000-pound (14,000 kg) orbital payload by 2,000 to 5,000 pounds (900 to 2,300 kg), reducing the equipment that could be carried or the duration of the mission or both. The cost of construction of a Titan III facility, including the purchase of the land, was estimated to cost $31 million (equivalent to $187 million in 2018), and the required supporting ground equipment would cost another $79 million (equivalent to $477 million in 2018).[82]

The announcement that the MOL would be launched from the Western Test Range caused an outcry in the Florida news media, which decried it as a wasteful duplication of facilities, given that the recently completed $154 million (equivalent to $929 million in 2018) Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 41 was specifically built to handle Titan III launches. The Chairman of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Congressman George P. Miller from California, convened a special session on the MOL Program on 7 February 1966. The first witness, the Associate Administrator of NASA, Robert Seamans, supported the MOL Program, and the decision to launch satellites into polar orbit from the West Coast, and said that NASA planned to launch weather satellites from there. He was followed by Schriever, who detailed the issues involved. The arguments did not satisfy Floridians. Hearings in the House were followed by ones in the Senate before the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences on 24 February, chaired by the influential Senator Clinton P. Anderson. This time the witnesses were Seamans, Flax and John S. Foster Jr., Brown's successor as DDR&E. The logic of the arguments and the united front presented dampened criticism, and none of the nine members of the House from Florida opposed the 1966 MOL budget allocation.[83]

The USAF attempted to purchase the land to the south of Vandenberg Air Force Base for the new space launch complex from the owners, but negotiations failed to reach agreement on a suitable price. The government then went ahead and condemned the land under eminent domain, compulsorily acquiring 14,404.7 acres (5,829.4 ha) from the Sudden Ranch and 499.1 acres (202.0 ha) from the Scolari Ranch for $9,002,500 (equivalent to $54.3 million in 2018). Ground was broken on the new Space Launch Complex 6 (SLC 6) on 12 March 1966.[84] Work on preparing the site was completed on 22 August. This involved 1.4 million cubic yards (1.1 million cubic metres) of earthworks, and the construction of access roads, a water supply pipeline and a railroad siding.[85]

By this time, the design of the launch complex had progressed to the point at which it was possible to call for bids for its construction. Major items included a launch pad, umbilical tower, mobile services tower, aerospace ground equipment (AGE) building, propellant loading and storage systems, launch control center, segment receipt inspection building, ready building, protective clothing building, and complex service building.[86] Seven bids for the construction contract were received, and it was awarded to the lowest bidder, Santa Fe and Stolte of Lancaster, California. The contract was valued at $20.2 million (equivalent to $122 million in 2018).[87][88] Construction work was overseen by the United States Army Corps of Engineers. The launch control center, segment receipt inspection building and ready building were accepted by the USAF in August 1968.[89]

Easter Island

Like the NASA Gemini, the Gemini B spacecraft would splashdown in the Atlantic or Pacific oceans. In the event of an abort, it could have come down in the eastern Pacific Ocean. On 26 July 1968, an agreement was reached with Chile for the use of Easter Island as a staging area for search and rescue aircraft and helicopters.[90] Works included resurfacing the 6,600-foot (2,000 m) runway, taxiways and parking areas and with asphalt, and establishing communications, aircraft maintenance and storage facilities, and accommodation for 100 personnel.[91]

Rochester

A Camera Optical Assembly (COA) facility was constructed at Eastman Kodak in Rochester, New York. It included a new steel frame building and a masonry building with 141,200 square feet (13,120 m2) of test chambers, built at a cost $32,500,000.[92] The laboratory was dug into the ground so observers would not realise how large it was.[73]

Test flight

MOL Test flight OPS 0855 was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 40 on 3 November 1966 at 13:50:42 UTC, on a Titan IIIC-9. The flight consisted of a MOL mockup built from a Titan II propellant tank, and the refurbished capsule from the Gemini 2 mission as a prototype Gemini B spacecraft. This was the first time an American spacecraft intended for human spaceflight had flown in space twice, albeit without a crew. The simulated laboratory contained eleven experiments.[93][94]

After the Gemini B prototype separated for a sub-orbital reentry, the MOL mockup continued into orbit and released three satellites. A hatch installed in the Gemini's heat shield—intended to provide access to the MOL during crewed operations—was tested during the capsule's reentry. The Gemini capsule was recovered near Ascension Island in the South Atlantic by the USS La Salle after a flight of 33 minutes.[94]

Public responses

With the 1966 Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament approaching, there were concerns about how the MOL was viewed by the international community. The US insisted that the MOL was in line with the 17 October 1963 United Nations General Assembly resolution that the exploration and use of outer space should be used only "for the betterment of mankind". To allay Soviet fears that the MOL would carry nuclear weapons, the State Department suggested that Soviet officials be permitted to inspect it for them before launch, but Brown opposed this on security grounds.[95]

Public debate of the merits of the MOL program was hobbled by its semi-secret nature. Writing about the MOL as an outsider in 1967, Leonard E. Schwartz, a consultant to the Directorate for Scientific Affairs of the OECD, noted that the US already had SAMOS satellites for reconnaissance and Vela satellites for surveillance of nuclear explosions, but without knowing their capabilities or those of MOL, could not evaluate the actual costs or benefits of the program.[96]

Publicly, the Air Force vaguely described the MOL as "an effective space building block of very substantial potential, a space resource capable of growth to follow-on tasks."[97] "On completion", Brady declared in 1965, "we will have configured, acquired, and most important, conducted a manned military space operation thereby acquiring the crews, experience and equipment that will, if required, allow the Air Force to move into the near-earth space environment in an orderly and effective manner."[98]

The Soviet Union commissioned the development of its own military space station, Almaz. Three Almaz space stations flew as Salyut space stations, and the program also developed a military add-on used on Salyut 6 and Salyut 7.[99][100][101]

Delays and cost increases

Within weeks of the President's announcement of the MOL Program, it was facing budget cuts. In November 1965, Flax arbitrarily cut $20 million (equivalent to $124 million in 2018) from the MOL Program's fiscal year 1967 budget, bringing it down to $374 million. Brown learned that McNamara intended to limit the program to $150 million (equivalent to $905 million in 2018) in fiscal year 1967, the same allocation as in fiscal year 1966, in response to the rising cost of the Vietnam War.[102] In August 1965, the first uncrewed qualification flight had been expected to take place in late 1968, with the first crewed mission in early 1970,[103][104] on the assumption that engineering development would commence in January 1966. Since this was now unlikely, McNamara saw no reason to continue with the original budget. Brown examined the schedules, and advised McNamara that a crewed mission in April 1969 would require a minimum of $294 million (equivalent to $1.77 billion in 2018) in fiscal year 1967, and that the minimum budget that the MOL Program required was $230 million, which would impose a delay of the first flight of three to eighteen months. McNamara was unmoved, and $150 million was the sum requested in the President's budget submitted to Congress in January 1966.[102]

When the MOL engineering development phase commenced in September 1966, it became clear that the USAF estimates of project costs and those of the major contractors were a long way apart. McDonnell requested $205.5 million (equivalent to $1.24 billion in 2018) for a fixed price plus incentive fee (FPIF) contract to design and build Gemini B, which the USAF budgeted $147.9 million; Douglas wanted $815.8 million for the laboratory vehicles which the USAF budgeted at $611.3 million; and General Electric sought $198 million (equivalent to $1.19 billion in 2018) for work budgeted at $147.3 million. In response the MOL SPO reopened negotiations for systems not under contract, and halted the issuance of Dorian clearances to contractor personnel. This had the desired effect, and by December the major contractors had reduced their prices, bringing them closer to the USAF estimates. However, on 7 January, the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) informed the MOL SPO that it intended to limit contracts in fiscal year 1968 to $430 million, which was $157 million short of what the MOL SPO wanted, and $381 below what the contractors wanted. This meant that the prime contracts had to be renegotiated,[45]

Budget cuts were not the only reason for the project's schedule slipping. On 9 December 1966, Eastman Kodak advised that it would not be able to deliver the optical sensors by the original target date of January 1969 for a crewed mission in April, and asked for a ten-month extension to October 1969, which pushed the date of the first crewed mission back to January 1970.[92] Eventually, $480 million (equivalent to $2.9 billion in 2018) was found for fiscal year 1968, with $50 million (equivalent to $302 million in 2018) obtained by reprogramming funds from other programs, and $661 million agreed upon for fiscal year 1969.[105] To meet this, the date of the first qualification flight was pushed back still further, to December 1970, with the first crewed mission in August 1971.[103][104]

Contracts were signed in May 1967. On 17 May, a $674,703,744 FPIF contract (equivalent to $3.96 billion in 2018) was signed with Douglas, which also received $13 million (equivalent to $76.2 million in 2018) in black funds. A $180,469,000 FPIF contract (equivalent to $1.06 billion in 2018) was signed with McDonnell the following day, and a $110,020,000 (equivalent to $664 million in 2018) to General Electric, which was expected to receive another $60 million in black funds (equivalent to $352 million in 2018).[105][106] The delays increased the projected costs of the MOL Program to $2.35 billion (equivalent to $14.2 billion in 2018).[105] Aware of the program's budgetary and political difficulties, the astronauts in early 1968 advised MOL deputy director, General Joseph S. Bleymaier, to eliminate the unmanned qualification missions; the August 1971 manned flight would be the first MOL launch and first operational mission.[103] In March 1968, Congress appropriated $515 million for fiscal year 1969, and the MOL SPO was directed to plan on the basis of a $600 million appropriation (equivalent to $3.62 billion in 2018) for fiscal year 1970. This entailed yet another schedule slippage. On 15 July 1968, the MOL SPO convened a conference with major contractors in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and it was agreed to defer the first crewed mission from August to December 1971.[107]

Cancellation

A few months after MOL development began, the program also began developing KH-10 Dorian, an automated MOL that replaced the crew compartment with film reentry vehicles. In February 1966, Schriever commissioned a report examining humans' usefulness on the station. The report, which was submitted on 25 May, concluded that they would be useful in several ways, but implied that the program would always need to justify the cost and difficulty of manned MOL versus the unmanned version. Although it did not fly until July 1966, the authors were aware of the capabilities of the KH-8 Gambit 3. While it could not achieve the same resolution as the Dorian camera on MOL,[108] and the automation equipment would require longer development time and add weight,[109] Dorian had a resolution of 13 to 15 inches (33 to 38 cm), and could remain on orbit longer, and carry more film than earlier spy satellites.[110] As the unmanned system's technology improved, those within the MOL program increasingly feared that astronauts were being eliminated. Crews said "it became obvious that all we were was a backup in case the unmanned reconnaissance system didn't work".[111] Although Crippen did not think automation could not completely replace astronauts, he agreed with Crews that the unmanned system was quickly improving.[112]

The 1966 report pointed out that crewed systems had many advantages over automated ones, which lost up to half their images to cloud cover on a typical mission. A human could select the best angle for a photograph, and could switch between color and infrared, or some other special film, depending on the target. This was especially useful for dealing with camouflaged targets. The MOL also had the ability to change orbits, and could shift from its regular 80-nautical-mile (150 km) orbit to a 200-to-300-nautical-mile (370 to 560 km) one, giving it a view of the entire Soviet Union.[113] Experience on Projects Mercury, Gemini and the X-15 had demonstrated that crew initiative, innovation and improvisation was often the difference between success and failure of the mission.[108] The practicality of human reconnaisance from space was demonstrated on the Gemini 5 mission, which conducted 17 USAF military experiments, including photographing missile launches from Vandenberg Air Force Base, and observations of the White Sands Proving Ground.[114]

Debate also persisted about the value of the very high resolution (VHR) imaging being developed for the MOL and KH-9 Hexagon, or whether the resolution provided by Gambit 3 was sufficient.[115] After the Liberty incident in June 1967 and the Pueblo incident in January 1968, there was an increased focus on intelligence gathering by satellite. The Director of Central Intelligence, Richard M. Helms, commissioned a report on the value of VHR, which was completed in May 1968. It concluded that it would help identify smaller items and features, and increase the understanding of Soviet procedures and processes, and the capacities of some of its industrial facilities, it would not alter estimates of technical capabilities, or assessments of the size and deployment of forces. Whether the benefit justified the cost was unclear,[114] but by 1968 USAF decided that the unmanned system's longer development time and less certain capability meant that first MOL missions had to be manned. Later ones could be manned or unmanned as needed.[116]

On 20 January 1969, Richard Nixon was sworn in as President.[117] He instructed the director of the new Bureau of the Budget, Robert Mayo, and the Secretary of Defense, Melvin Laird, to find ways to cut defense spending.[110] The MOL was an obvious target; an article in the Washington Monthly titled "How The Pentagon Can Save $9 Billion", written by Robert S. Benson, a former Department of Defense employee, described the MOL as a program that "receives a half a billion dollars a year and ought to rank dead last on any rational scale of national priorities."[118] Stewart briefed the new Deputy Secretary of Defense, David Packard, on the MOL, which Stewart described as the best path to VHR at the earliest date. Laird, who as a Congressman had criticized McNamara for inadequately funding the MOL Program, was favorably disposed towards the MOL Program, as was Seamans, who was now the Secretary of the Air Force. On 6 March, Packard directed Foster to proceed on the basis of $556 million for fiscal year 1970 (equivalent to $2.98 billion in 2018). This entailed postponement of the first crewed mission to February 1972.[119]

The Bureau of the Budget did not accept Laird's decision. Mayo argued that the resolution provided by Gambit 3 was adequate, and proposed canceling both the MOL and Hexagon. An MOL mission was expected to cost $150 million (equivalent to $804 million in 2018), but a Gambit 3 launch only cost $23 million (equivalent to $123 million in 2018). The value of VLR, Mayo argued, was not worth the additional cost. On 9 April, Nixon reduce the MOL's funding to $360 million, and canceled Hexagon. This meant further postponement of the first crewed flight, by up to a year, and the Bureau of the Budget continued to press for the MOL to be cancelled. In a last ditch attempt to save the MOL, Laird, Seamans and Stewart met with Nixon at the White House on 17 May, and briefed him on the history of the program. Seamans even offered to find $250 million (equivalent to $1.34 billion in 2018) to continue the program from elsewhere in the USAF budget. They thought the meeting went well, but Nixon accepted the Bureau of the Budget's recommendation to cancel the MOL and proceed with Hexagon instead.[120]

On 7 June 1969, Stewart ordered Bleymaier to cease all work on Gemini B, the Titan IIIM and the MOL spacesuit, and to cancel or curtail all other contracts. The official announcement that the MOL was canceled was made on 10 June.[121][122]

Legacy

MOL might have been the world's first manned space station.[60] Crews believed that unmanned systems were probably superior, and said that when he saw high-resolution photographs from Gambit 3 he knew that MOL would be canceled.[111][108] "Looking back on it now", he said, "it's obvious that our country had decided to put everything into the civilian part of the space program".[112] Some believed that MOL should have launched astronauts before the optics were ready.[123][124] Abrahamson later agreed that his and other MOL astronauts' advice to fly the first mission fully operational was a mistake. He learned while serving as Deputy Administrator of NASA in the early 1980s that launching anything, even "an empty can", made cancellation of a project less likely.[103][60]

Following the decision to cancel MOL, a committee was formed to handle the disposal of its property, valued at $12.5 million (equivalent to $67 million in 2018). The Acquisition and Tracking System, Mission Development Simulator, Laboratory Module Simulator, and Mission Simulator were transferred to NASA by the end of 1973. The MOL program office at the Pentagon closed on 15 February 1970, and the office in Los Angeles on 30 September 1970. The Director of Space Systems, Brigadier General Lew Allen, became the point of contact for MOL Contracts were terminated, but those with Aerojet, McDonnell Douglas, and the United Technologies Corporation (UTC) remained open in June 1973.[125] The Aerojet contract had only small claims totaling $9,888 (equivalent to $53 thousand in 2018), but there remained reservations of $771,569 (equivalent to $3.4 million in 2018) on the McDonnel-Douglas contract due to a subcontractor dispute and California Franchise Tax. The UTC contract was still worth up to $51 million (equivalent to $225 million in 2018), with the actual amount depending on how much work was attributable to the MOL, and how much to the ongoing work on Titan III.[126]

At the time of the MOL was cancelled, 192 service and 100 civilian personnel were employed on MOL activities. Within weeks, 80 percent of the service personnel were given new duty assignments. The civilians were reassigned to the Space and Missile Systems Organization (SAMSO).[127] Fourteen of the seventeen MOL astronauts remained in the program.[128] Finlay returned to the US Navy in April 1968,[129] and Adams left in July 1966 to join the X-15 Program. He flew in space on his seventh flight on 5 November 1967, only to be killed when his aircraft broke up.[130] Lawrence, the first African-American to be selected as an astronaut, was killed in an F-104 crash at Edwards Air Force Base on 8 December 1967.[131] All but Herres wanted to transfer to NASA. They flew to Houston to meet with NASA's Director of Flight Crew Operations, Deke Slayton, who told them that he did not need more astronauts. George Mueller, NASA's Deputy Administrator, saw things differently; sooner or later NASA would need help from the USAF, and maintaining good relations with it was good policy. Slayton agreed to take the seven of them aged 35 or younger as NASA Astronaut Group 7. NASA also took Crews, although as a test pilot rather than an astronaut, and he would continue flying NASA aircraft until 1994.[94][132][133] All seven eventually flew Space Shuttle missions.[134] Those that did not transfer to NASA could not fight in combat for three years because of the risk of capture. Not being able to serve in Vietnam hurt their careers, and some soon left the military.[124]

The Titan III booster eventually became a mainstay of the military satellite program. The Titan IIIC version was capable of lifting 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) into low Earth orbit;[135] its successor, the Titan IIID developed for Hexagon,[136] could lift 30,000 pounds (14,000 kg), and the Titan IIIM developed for the MOL would have been able to lift 38,000 pounds (17,000 kg). In this, it competed with NASA's Saturn IB, which could lift 36,000 pounds (16,000 kg). This could be considered a case of wasteful duplication, but the cost of a Titan IIIM launch was half that of Saturn IB.[135] The Titan IIIM never flew, but the UA1207 solid rocket boosters developed for the MOL were eventually used on the Titan IV,[137] and the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster were based on materials, processes and the UA1207 design developed for MOL, with only minor changes.[138] NASA also used work on the Gemini B space suits for the agency's own suits, MOL's waste management system flew on Skylab, and NASA Earth Science used other MOL equipment.[94] The prototype IMLSS is also in the National Museum of the United States Air Force.[67] Six honeycombed borosilicate glass mirrors made by Corning for MOL, each with a diameter of 72 inches (1.8 m), were combined to make the Multiple Mirror Telescope in Arizona, the third largest optical telescope in the world at the time of its dedication.[139]

Work on Space Launch Complex 6 was 92 percent complete. The main task remaining was conducting acceptance demonstration tests. It was decided to complete the construction and tests, but not install AGE, and then place the facility in caretaker status, with a caretaker crew provided by the 6595th Aerospace Test Wing.[140] In 1972, the USAF decided to refurbish SLC 6 for use with the Space Shuttle.[141] This cost more than anticipated, some $2.5 billion (equivalent to $5.22 billion in 2018), and the date of the first launch had to be postponed from June 1984 to July 1986.[142] The airport runway at Easter Island developed for MOL was extended by an additional 1,420 feet (430 m) to 11,055 feet (3,370 m) to allow for an emergency Space Shuttle landing and a piggyback retrieval by a modified Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, at a cost of $7.5 million (equivalent to $15.2 million in 2018).[143][144] Preparations were underway for STS-62-A, the launch of the Space Shuttle Discovery from SLC 6, commanded by MOL astronaut Bob Crippen, with NRO director Edward C. Aldridge Jr. on board, when the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster occurred in January 1986. Plans for Space Shuttle launches from SLC 6 were abandoned, and none ever flew from there. No Space Shuttle was ever launched into a polar orbit. Starting in 2006, SLC 6 was used for Delta IV launches, including NRO KH-11 Kennan satellites.[142][145]

Some items of MOL equipment made their way to museums. The spacecraft used in the only flight of the MOL program is on display at the Air Force Space and Missile Museum at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.[146] A Gemini B spacecraft used for ground-based testing is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio (on loan from the National Air and Space Museum). Like the other Gemini B capsule, it is differentiated from the NASA Gemini spacecraft by the words "U.S. AIR FORCE" painted on it, with accompanying insignia, and by the circular hatch cut through its heat shield.[147] Two MH-7 training space suits from the MOL program were discovered in a locked room in the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 5 museum on Cape Canaveral in 2005.[148] Crippen donated his MOL space suit to the National Air and Space Museum in 2017.[149][150]

In July 2015, the NRO declassified over 800 files and photos related to the MOL program.[151] It produced a book by historian Courtney V.K. Homer about the MOL program, Spies in Space (2019), based upon the trove of documents released by the NRO and with interviews she conducted with Abrahamson, Bobko, Crippen, Crews, Macleay, and Truly.[152][124]

Notes

- Berger 2015, p. 2.

- Divine 1993, p. 11.

- David 2017, p. 768.

- Homer 2019, pp. 2–3.

- Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, pp. 28–29, 37.

- Homer 2019, p. 1.

- Divine 1993, pp. 11–12.

- Wheeldon 1998, p. 33.

- Day 1998, p. 49.

- Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, pp. 101–102.

- Berger 2015, p. 4.

- Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 71.

- Berger 2015, p. 5.

- Berger 2015, pp. 6–8.

- Houchin 1995, p. 273.

- Houchin 1995, p. 279.

- Erickson 2005, p. 353.

- Houchin 1995, p. 311.

- Berger 2015, p. 10.

- Zuckert, Eugene (25 August 1962). "Memorandum for Director, Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) Program – Subject: Authorization To Proceed With MOL Program" (PDF). Department of Defence. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Hacker & Grimwood 2010, pp. 120–122.

- Berger 2015, pp. 25–27.

- Erickson 2005, pp. 370–371.

- "Air Force to Develop Manned Orbiting Laboratory" (PDF) (Press release). Department of Defence. 10 December 1963. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Berger 2015, pp. 37–38.

- Erickson 2005, pp. 378–379.

- Homer 2019, p. 8.

- Berger 2015, p. 36.

- Homer 2019, pp. 4–5.

- Berger 2015, pp. 43–44.

- Berger 2015, p. 40.

- Stewart, James T. (14 February 1968). "Designation of MOL as the KH-10 Photographic Reconnaissance Satellite System" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Berger 2015, pp. 40–41.

- Homer 2019, p. 45-46.

- Brady 1965, pp. 93–94.

- Berger 2015, pp. 71–79.

- "Information and Publicity Controls" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 16 August 1965. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "President Johnson's Statement on MOL" (PDF) (Press release). National Reconnaissance Office. 25 August 1965. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Berger 2015, p. 61.

- "Major General Harry L. Evans > U.S. Air Force > Biography Display". United States Air Force. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Maj Gen Harry L. Evans, USAF (Ret.)". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Homer 2019, p. 14.

- Berger 2015, p. 85.

- Berger 2015, p. 103.

- Berger 2015, p. 143.

- Berger 2015, pp. 85–88.

- Strom 2004, p. 12.

- United States Air Force (8 May 1968). MOL Flight Test and Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Los Angeles: Department of the Air Force, Maimed Orbiting Laboratory, Systems Program Office. p. 2-2. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Homer 2019, p. 20.

- "MOL 3". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "MOL 4". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "MOL 5". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "MOL". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "MOL 6". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "MOL 7". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "MOL LM". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- Day, Dwayne A. (26 March 2018). "The measure of a man: Evaluating the Role of Astronauts in the Manned Orbiting Laboratory Program (Part 2)". The Space Review. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- Homer 2019, p. 49-52.

- Advanced MOL Planning (PDF), National Reconnaissance Office (published 1 July 2015), 1969, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2015

- Winfrey, David (16 November 2015). "The last spacemen: MOL and what might have been". The Space Review.

- "Gemini-B". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Gemini B RM". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Gemini B NASA-Gemini's Air Force Twin" (PDF). Historic Space Systems. September 1996. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Brady 1965, p. 97.

- Thomas & McMann 2006, pp. 212–219.

- Thomas & McMann 2006, pp. 223–230.

- Thomas & McMann 2006, pp. 230–233.

- Eppley 1963, pp. 11–13.

- Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. xxvi–xxvii.

- Homer 2019, p. 29.

- Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 2–3.

- Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 5–6.

- Homer 2019, p. 59.

- Homer 2019, p. 31,34.

- Homer 2019, p. 35.

- Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 23–25.

- Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 26.

- Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 26–28.

- Homer 2019, p. 30.

- Homer 2019, p. 54.

- Homer 2019, pp. 55–58.

- Brown, Harold (14 March 1966). "Memorandum for Chairman Revers from Harold Brown, Subject: Determination of the Launch Site for MOL" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Berger 2015, pp. 118–123.

- Geiger 2014, p. 163.

- Ferguson, James (6 October 1966). "Manned Orbiting Laboratory Monthly Status Report" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "MOL Program Plan, Volume 1 of 2" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 15 June 1967. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Homer 2019, p. 61.

- "Manned Orbiting Laboratory Monthly Status Report" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 7 February 1967. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Bleymaier, Joseph (24 September 1968). "MOL Monthly Management Report: 25 July −25 August 68" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Homer 2019, p. 19.

- Ferguson, James (22 October 1966). "Use of Easter Island for MOL Program" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Berger 2015, p. 108.

- "SSLV-5 NO. 9 Post Firing Flight Test Report (Final Evaluation Report) and Mol EFT Final Flight Test Report". Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "50 Years Ago: NASA Benefits from MOL Cancellation". NASA. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Homer 2019, p. 73.

- Schwartz 1967, pp. 54–56.

- Brady 1965, p. 99.

- Brady 1965, p. 08.

- "The Almaz program". Russian Space Web. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- Wade, Mark. "Almaz". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- Grahn, Sven. "The Almaz Space Station Program". Sven's Space Place. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- Berger 2015, p. 107.

- Day, Dwayne (2 November 2015). "Blue Suits and Red Ink: Budget Overruns and Schedule Slips of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory Program". The Space Review. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "MOL Program Chronology" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. December 1967. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Berger 2015, p. 145.

- "Manned Orbiting Laboratory Monthly Status Report:" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 5 June 1967. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Berger 2015, pp. 150–151.

- Day, Dwayne A. (19 March 2018). "The Measure of a Man: Evaluating the Role of Astronauts in the Manned Orbiting Laboratory Program (Part 1)". The Space Review. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Homer 2019, p. 69-70.

- David 2017, p. 769.

- Homer 2019, p. 71.

- Homer 2019, pp. 89.

- Berger 2015, p. 102.

- Berger 2015, pp. 148–149.

- Homer 2019, pp. 74–75.

- Homer 2019, pp. 72.

- Berger 2015, p. 155.

- Berger 2015, p. 157.

- Berger 2015, pp. 156–157.

- Berger 2015, pp. 158–162.

- Berger 2015, pp. 162–163.

- Heppenheimer 1998, pp. 204–205.

- Berger 2015, p. 172.

- Day, Dwayne (26 August 2019). "Review: Spies in Space". The Space Review. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Homer 2019, pp. 92–93.

- "MOL Status" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 5 June 1973. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Homer 2019, p. 90.

- Homer 2019, p. 87.

- Shayler & Burgess 2017, p. 230.

- "X-15 Biography – Michael J. Adams". NASA. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Homer 2019, pp. 40–41.

- Homer 2019, pp. 91–92.

- Slayton & Cassutt 1994, pp. 249–251.

- Shayler & Burgess 2017, pp. 324–331.

- Heppenheimer 1998, p. 199.

- Heppenheimer 2002, p. 78.

- "Titan 3M". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- United Technology Center 1972, p. 2-117.

- Day, Dwayne A. (11 February 2008). "All Along the Watchtower". The Space Review. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Review of MOL Residuals" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 1 August 1968. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Heppenheimer 2002, pp. 81–83.

- Heppenheimer 2002, pp. 362–366.

- Boadle, Anthony (30 June 1985). "Lonely Easter Island Will Be Emergency Shuttle Landing Site". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Boadle, Anthony (17 August 1987). "Emergency space shuttle landing strip opened". UPI Archives. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Ray, Justin (8 February 2016). "Slick 6: 30 years after the hopes of a West Coast space shuttle". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Gemini Capsule". Air Force Space & Missile Museum. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- "Gemini Spacecraft". National Museum of the US Air Force. 5 April 2020.

- Nutter, Ashley (2 June 2005). "Suits for Space Spies". NASA. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- "Spacesuits Open Doors to MOL History". NASA. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Pressure Suit, Manned Orbiting Laboratory". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Index, Declassified Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) Records". National Reconnaissance Office. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Homer 2019, pp. v–vii.

References

- Berger, Carl (2015). "A History of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory Program Office". In Outzen, James D. (ed.). The Dorian Files Revealed: The Secret Manned Orbiting Laboratory Documents Compendium (PDF). Chantilly, Virginia: Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance. ISBN 978-1-937219-18-5. OCLC 966293037. Retrieved 4 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brady, William D. (November 1965). "The Manned Orbiting Laboratory Program". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 134 (1): 93–99. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb56144.x. ISSN 1749-6632.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- David, James Edward (2017). "How Much Detail Do We Need To See? High and Very High Resolution Photography, GAMBIT, and the Manned Orbiting Laboratory". Intelligence and National Security. 32 (6): 768–781. doi:10.1080/02684527.2017.1294372. ISSN 0268-4527.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, Dwayne (1998). "The Development and Improvement of the Corona Satellite". In Dwayne A., Day; John M., Logsdon; Latell, Brian (eds.). Eye in the Sky: The Story of the Corona Spy Satellites. Smithsonian History of Aviation Series. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 48–85. ISBN 1-56098-830-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Divine, Robert A. (1993). The Sputnik Challenge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505008-0. OCLC 875485384.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eppley, Charles V. (March 1963). History of the USAF Experimental Test Pilot School 4 February 1951 – 12 October 1961 (PDF). Edwards Air Force Base: United States Air Force. OCLC 831992420. Retrieved 5 February 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Erickson, Mark (2005). Into the Unknown Together: The DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University Press. ISBN 1-58566-140-6. OCLC 760704399. Retrieved 8 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geiger, Jeffrey E. (2014). Camp Cooke and Vandenberg Air Force Base, 1941-1966: From Armor and Infantry Training to Space and Missile Launches. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-7855-2. OCLC 857803877.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hacker, Barton C.; Grimwood, James M. (2010) [1977]. On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini (PDF). NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. ISBN 978-0-16-067157-9. OCLC 945144787. NASA SP-4203. Retrieved 8 April 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heppenheimer, T. A. (1998). The Space Shuttle Decision (PDF). Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-58834-014-7. OCLC 634841372. SP-4221. Retrieved 19 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heppenheimer, T. A. (2002). Development of the Space Shuttle 1972–1981. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-288-34009-5. OCLC 931719124. SP-4221.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Homer, Courtney V. K. (2019). Spies in Space: Reflections on National Reconnaissance and the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (PDF). Chantilly, Virginia: Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance. ISBN 978-1-937219-24-6. OCLC 1110619702. Retrieved 31 March 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Houchin, Roy Franklin II (1995). The Rise and Fall of Dyna-Soar: A History of Air Force Supersonic R&D, 1944-1963 (PDF) (PhD). Auburn, Alabama: Auburn University. OCLC 34181904. Retrieved 8 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schwartz, Leonard E. (January 1967). "Manned Orbiting Laboratory-for War or Peace?". International Affairs. 43 (1): 51–64. doi:10.2307/2612515. ISSN 1468-2346. JSTOR 2612515.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shayler, David J.; Burgess, Colin (2017). The Last of NASA's Original Pilot Astronauts. Chichester: Springer-Praxis. ISBN 978-3-319-51012-5. OCLC 1023142024.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Slayton, Donald K.; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle. New York: Forge. ISBN 978-0-312-85503-1. OCLC 937566894.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strom, Steven R. (Summer 2004). "The Best Laid Plans: A History of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory" (PDF). Crosslink. 5 (2): 11–15. ISSN 1527-5272. Retrieved 13 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swenson, Loyd S. Jr.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1966). This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury (PDF). The NASA History Series. Washington, DC: NASA. OCLC 569889. SP-4201. Retrieved 9 September 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, Kenneth S.; McMann, Harold J. (2006). US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-387-27919-9. OCLC 751800019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- United Technology Center (15 March 1972). Study of Solid Rocket Motors for a Space Shuttle Booster Final Report (PDF) (Report). Volume II: Technical Report. Huntsville, Alabama: George C. Marshall Space Flight Center. UTC 4205-72-7. Retrieved 19 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wheeldon, Albert D. (1998). "Corona: A Triumph of American Technology". In Dwayne A., Day; John M., Logsdon; Latell, Brian (eds.). Eye in the Sky: The Story of the Corona Spy Satellites. Smithsonian History of Aviation Series. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 29–47. ISBN 1-56098-830-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manned Orbiting Laboratory. |

- Declassified MOL files by the National Reconnaissance Office

- SSLV-5 No. 9 Post Firing Flight Test Report (Final Evaluation Report) and MOL-EFT Final Flight Test Report (Summary)