Edward Albee

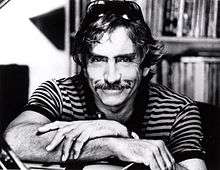

Edward Franklin Albee III (/ˈɔːlbiː/ AWL-bee; March 12, 1928 – September 16, 2016) was an American playwright known for works such as The Zoo Story (1958), The Sandbox (1959), Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962), A Delicate Balance (1966), and Three Tall Women (1994). Some critics have argued that some of his work constitutes an American variant of what Martin Esslin identified and named the Theater of the Absurd.[1] Three of his plays won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, and two of his other works won the Tony Award for Best Play.

Edward Albee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Edward Franklin Albee III March 12, 1928 Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | September 16, 2016 (aged 88) Montauk, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Dramatist |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1958–2016 |

| Notable works | Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The Zoo Story A Delicate Balance The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? Three Tall Women |

| Notable awards | Pulitzer Prize for Drama Tony Award for Best Play National Medal of Arts Special Tony Award America Award in Literature |

| Partner | Jonathan Thomas (esp. 1971; his death 2005) |

His works are often considered frank examinations of the modern condition. His early works reflect a mastery and Americanization of the Theatre of the Absurd that found its peak in works by European playwrights such as Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco, and Jean Genet.

His middle period comprised plays that explored the psychology of maturing, marriage, and sexual relationships. Younger American playwrights, such as Paula Vogel, credit Albee's mix of theatricality and biting dialogue with helping to reinvent postwar American theatre in the early 1960s. Later in life, Albee continued to experiment in works such as The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? (2002).

Early life

Edward Albee was born in 1928. He was placed for adoption two weeks later and taken to Larchmont, New York, where he grew up. Albee's adoptive father, Reed A. Albee, the wealthy son of vaudeville magnate Edward Franklin Albee II, owned several theaters. His adoptive mother, Reed's second wife, Frances (Cotter), was a socialite.[2][3] He later based the main character of his 1991 play Three Tall Women on his mother, with whom he had a conflicted relationship.[4]

Albee attended the Rye Country Day School, then the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey, from which he was expelled.[2] He then was sent to Valley Forge Military Academy in Wayne, Pennsylvania, where he was dismissed in less than a year.[5] He enrolled at The Choate School (now Choate Rosemary Hall) in Wallingford, Connecticut,[6] graduating in 1946. He had attracted theatre attention by having scripted and published nine poems, eleven short stories, essays, a long act play, Schism, and a 500-page novel, The Flesh of Unbelievers (Horn, 1) in 1946. His formal education continued at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, where he was expelled in 1947 for skipping classes and refusing to attend compulsory chapel.[6]

Albee left home for good in his late teens. In a later interview, he said: "I never felt comfortable with the adoptive parents. I don't think they knew how to be parents. I probably didn't know how to be a son, either."[7] In a 1994 interview, he said he left home at 18 because "[he] had to get out of that stultifying, suffocating environment."[4] In 2008, he told interviewer Charlie Rose that he was "thrown out" because his parents wanted him to become a "corporate thug" and did not approve of his aspirations to become a writer.[8]

Career

Albee moved into New York's Greenwich Village,[5] where he supported himself with odd jobs while learning to write plays.[9] Primarily in his early plays, Albee's work had various representations of the LGBTQIA community often challenging the image of a heterosexual marriage.[10] Despite challenging society's views about the gay community, he did not view himself as an LGBT advocate.[10] Albee's work typically criticized the American dream.[10] His first play, The Zoo Story, written in three weeks,[11] was first staged in Berlin in 1959 before premiering Off-Broadway in 1960.[12] His next, The Death of Bessie Smith, similarly premiered in Berlin before arriving in New York.[13]

Albee's most iconic play, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, opened on Broadway at the Billy Rose Theatre on October 13, 1962, and closed on May 16, 1964, after five previews and 664 performances.[14] The controversial play won the Tony Award for Best Play in 1963 and was selected for the 1963 Pulitzer Prize by the award's drama jury, but was overruled by the advisory committee, which elected not to give a drama award at all.[15] The two members of the jury, John Mason Brown and John Gassner, subsequently resigned in protest.[16] An Academy Award-winning film adaptation of the play was released in 1966 starring Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, George Segal, and Sandy Dennis. In 2013, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[17]

Georgia State University English professor Matthew Roudane divides Albee’s plays into three periods: the Early Plays (1959–1966), characterized by gladiatorial confrontations, bloodied action and fight to the metaphorical death; the Middle Plays (1971–1987), when Albee lost favor of Broadway audience and started premiering in the U.S. regional theaters and in Europe; and the Later plays (1991–2016), received as a remarkable comeback and watched by appreciative audiences and critics the world over.[18]

According to The New York Times, Albee was "widely considered to be the foremost American playwright of his generation."[19]

The less-than-diligent student later dedicated much of his time to promoting American university theatre. He served as a distinguished professor at the University of Houston, where he taught playwriting. His plays are published by Dramatists Play Service[20] and Samuel French, Inc.

Achievements and honors

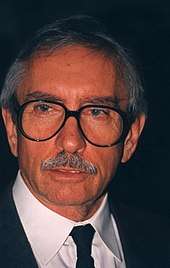

A member of the Dramatists Guild Council, Albee received three Pulitzer Prizes for drama—for A Delicate Balance (1967), Seascape (1975), and Three Tall Women (1994).

Albee was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1972.[21] In 1985, Albee was inducted into the American Theatre Hall of Fame.[22] In 1999, Albee received the PEN/Laura Pels Theater Award as a Master American Dramatist.[23] He received a Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement (2005);[24] the Gold Medal in Drama from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters (1980); as well as the Kennedy Center Honors and the National Medal of Arts (both in 1996).[25] In 2009, Albee received honorary degree from the Bulgarian National Academy of Theater and Film Arts (NATFA), a member of the Global Alliance of Theater Schools.

In 2008, in celebration of Albee's 80th birthday, a number of his plays were mounted in distinguished Off-Broadway venues, including the historic Cherry Lane Theatre where the playwright directed two of his early one-acts, The American Dream and The Sandbox.[26]

Philanthropy

Albee established the Edward F. Albee Foundation, Inc. in 1967, from royalties from his play Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. The foundation funds the William Flanagan Memorial Creative Persons Center (named after the composer William Flanagan, but better known as "The Barn") in Montauk, New York, as a residence for writers and visual artists.[27] The foundation's mission is "to serve writers and visual artists from all walks of life, by providing time and space in which to work without disturbance."[28]

Personal life and death

Albee was openly gay and stated that he first knew he was gay at age 12 and a half.[29] Albee was briefly engaged to Larchmont debutante Delphine Weissinger, and although their relationship ended when she moved to England, he remained a close friend of the Weissinger family. Growing up, he often spent more of his time in the Weissinger household than he did in his own, due to discord with his adoptive parents.

Albee insisted that he did not want to be known as a "gay writer," saying in his acceptance speech for the 2011 Lambda Literary Foundation's Pioneer Award for Lifetime Achievement: "A writer who happens to be gay or lesbian must be able to transcend self. I am not a gay writer. I am a writer who happens to be gay."[30] His longtime partner, Jonathan Richard Thomas, a sculptor, died on May 2, 2005 from bladder cancer. They had been partners from 1971 until Thomas's death. Albee also had a relationship of several years with playwright Terrence McNally during the 1950s.[31]

Albee died at his home in Montauk, New York on September 16, 2016, aged 88.[31][24][32]

Awards and nominations

|

|

Works

Plays

Works written or adapted by Albee:[39]

- The Zoo Story (1959)

- The Death of Bessie Smith (1960)

- The Sandbox (1960)

- Fam and Yam (1960)

- The American Dream (1961)

- Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962)

- The Ballad of the Sad Café (1963) (adapted from the novella by Carson McCullers)

- Tiny Alice (1964)

- Malcolm (1966) (adapted from the novel by James Purdy)

- A Delicate Balance (1966)

- Breakfast at Tiffany's (adapted from the novel by Truman Capote) (1966)

- Everything in the Garden (adapted from the play by Giles Cooper) (1967)

- Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung (1968)

- All Over (1971)

- Seascape (1975)

- Listening (1976)

- Counting the Ways (1976)

- The Lady from Dubuque (1980)

- Lolita (adapted from the novel by Vladimir Nabokov) (1981)

- The Man Who Had Three Arms (1982)

- Finding the Sun (1983)

- Walking (1984)

- Envy (1985)

- Marriage Play (1987)

- Three Tall Women (1991)

- The Lorca Play (1992)

- Fragments (1993)

- The Play About the Baby (1998)

- The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? (2000)

- Occupant (2001)

- Knock! Knock! Who's There!? (2003)

- Peter & Jerry, retitled in 2009 to At Home at the Zoo (Act One: Homelife. Act Two: The Zoo Story) (2004)

- Me Myself and I (2007)

Opera libretti

- Bartleby (adapted from the short story by Herman Melville) (1961)

- The Ice Age (1963, uncompleted)

Essays

- Stretching My Mind: Essays 1960–2005 (Avalon Publishing, 2005). ISBN 9780786716210.

See also

References

- Norwich, John Julius (1990). Oxford Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Arts. USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 10. ISBN 978-0198691372.

- Weber, Bruce (September 17, 2016). "Edward Albee, Trenchant Playwright for a Desperate Era, Dies at 88". The New York Times.

- Thorpe, Vanessa (September 17, 2016). "Edward Albee, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? playwright, dies aged 88". The Guardian. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- Markowitz, Dan (August 28, 1994). "Albee Mines His Larchmont Childhood". The New York Times. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Simonson, Robert (September 16, 2016). "Edward Albee, Towering American Playwright, Dies at 88". Playbill. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- Boehm, Mike (September 16, 2016). "Edward Albee, three-time Pulitzer-winning playwright and 'Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?' author, dies at 88". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- "Edward Albee Interview". Academy of Achievement. June 2, 2005. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- Edward Albee on Charlie Rose, May 27, 2008.

- Kennedy, Mark (September 16, 2016). "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? playwright Edward Albee dead at 88". Associated Press. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- Griffin, Gabriele (2002). Who's Who IN LESBIAN & GAY WRITING. 11 New Fetter Lane, London: Routledge. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-415-15984-9.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Reuben, Paul P. "Chapter 8: Edward Albee." Archived July 16, 2012, at Archive.today, Perspectives in American Literature- A Research and Reference Guide, Retrieved June 28, 2007

- "Plays Produced in the Provincetown Playhouse in 1960s Chronological". Provincetown Playhouse. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- Albee, Edward."The Death of Bessie Smith"The American Dream ; The Death of Bessie Smith ; Fam and Yam: Three Plays. Dramatists Play Service, Inc., 1962, ISBN 0-8222-0030-9, pp.46-48

- "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?", Playbill Vault. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- "US playwright Edward Albee dies aged 88". BBC News. September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- Kihss, Peter (May 2, 1967). "Albee Wins Pulitzer Prize; Malamud Novel is Chosen". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- "Library of Congress announces 2013 National Film Registry selections" (Press release). Washington Post. December 18, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- Roudané, Matthew (August 2017). "Overview: The Theater of Edward Albee". Edward Albee: A Critical Introduction. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Edward Albee, Trenchant Playwright Who Laid Bare Modern Life, Dies at 88". The New York Times. September 17, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- "Dramatists Play Service". Dramatists.com. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- "Broadway's Best". The New York Times. March 5, 1985.

- "Winners of the PEN/Laura Pels International Foundation for Theater Awards | PEN America". PEN. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- Howard, Adam (September 16, 2016). "Pulitzer Prize-Winning Playwright Edward Albee Dead at 88". NBC News. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- "Who We Are". The Edward F. Albee Foundation. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- Brantley, Ben (April 2, 2008). "A Double Bill of Plays, Both Heavy on the Bile". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- Grundberg, Andy (July 3, 1988). "The Artists of Summer". The New York Times.

- "Mission & History". The Edward F. Albee Foundation. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- Shulman, Randy (March 10, 2011). "Who's Afraid of Edward Albee?". Metro Weekly. Archived from the original on April 12, 2014.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Playwright Edward Albee defends 'gay writer' remarks". National Public Radio. June 6, 2011.

- Pressley, Nelson (September 16, 2016). "Edward Albee, Pulitzer-Winning Playwright of Modern Masterpieces, Dies at 88". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- Jones, Chris (September 16, 2016). "Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Edward Albee dies at age 88". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- Staff. "Albee's Loft; Edward Albee's 6,000-square-foot loft in a former cheese warehouse in New York's Tribeca neighborhood houses his expansive collection of fine art, utilitarian works and sculptures. (See related article.)", Wall Street Journal, March 11, 2010. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- Hohenberg, John. "A snub of Edward Albee". The Pulitzer Prize. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- Hohenberg, John. "A snub of Edward Albee". The Pulitzer Prize. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- Hohenberg, John. "A snub of Edward Albee". The Pulitzer Prize. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- "Recipients of the Saint Louis Literary Award". Saint Louis University. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- Crowder, Courtney. "Edward Albee wins Tribune's top award for writing". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- "Works". Edward Albee Society. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

Further reading

- Solomon, Rakesh H. Albee in Performance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Edward Albee |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Albee. |

- Edward F. Albee Foundation

- The Edward Albee Society

- Edward Albee scripts, 1949–1966, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Edward Albee on IMDb

- Edward Albee at AllMovie

- Edward Albee at the Internet Broadway Database

- Edward Albee at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Edward Albee Plays at the Newberry Library