Marlene Dietrich

Marie Magdalene "Marlene" Dietrich (/mɑːrˈleɪnə ˈdiːtrɪk/, German: [maʁˈleːnə ˈdiːtʁɪç] (![]()

Marlene Dietrich | |

|---|---|

_(Cropped).png) Dietrich as Monica Teasdale in No Highway in the Sky (1951) | |

| Born | Marie Magdalene Dietrich 27 December 1901 |

| Died | 6 May 1992 (aged 90) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Städtischer Friedhof III |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1919–1984 |

| Spouse(s) | Rudolf Sieber

( m. 1923; died 1976) |

| Children | Maria Riva |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

| |

In 1920s Berlin, Dietrich performed on the stage and in silent films. Her performance as Lola-Lola in The Blue Angel (1930), brought her international acclaim and a contract with Paramount Pictures. Dietrich starred in many Hollywood films such as Morocco (1930), Shanghai Express (1932) and Desire (1936). She successfully traded on her glamorous persona and "exotic" looks, and became one of the highest-paid actresses of the era. Throughout World War II, she was a high-profile entertainer in the United States. Although she still made occasional films after the war such as Witness for the Prosecution (1957), Dietrich spent most of the 1950s to the 1970s touring the world as a marquee live-show performer.

Dietrich was known for her humanitarian efforts during the war, housing German and French exiles, providing financial support and even advocating their American citizenship. For her work on improving morale on the front lines during the war, she received several honors from the United States, France, Belgium and Israel. In 1999, the American Film Institute named Dietrich the ninth greatest female screen legend of classic Hollywood cinema.[6]

Early life

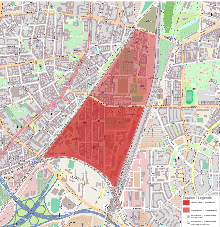

Dietrich was born on 27 December 1901 at Leberstraße 65 in the neighborhood of Rote Insel in Schöneberg, now a district of Berlin.[7] Her mother, Wilhelmina Elisabeth Josephine (née Felsing), was from an affluent Berlin family who owned a jewelry and clock-making firm. Her father, Louis Erich Otto Dietrich, was a police lieutenant. Dietrich had one sibling, Elisabeth, who was one year older. Dietrich's father died in 1907.[8] His best friend, Eduard von Losch, an aristocratic first lieutenant in the Grenadiers, courted Wilhelmina and married her in 1914, but he died in July 1916 from injuries sustained during the First World War.[7] Von Losch never officially adopted the Dietrich sisters, so Dietrich's surname was never von Losch, as has sometimes been claimed.[9]

Dietrich's family nicknamed her "Lena" and "Lene" (IPA: [leːnɛ]). Aged about 11, she combined her first two names to form the name "Marlene". Dietrich attended the Auguste-Viktoria Girls' School from 1907 to 1917[10] and graduated from the Victoria-Luise-Schule (today Goethe-Gymnasium) in Berlin-Wilmersdorf, in 1918.[11] She studied the violin[12] and became interested in theater and poetry as a teenager. A wrist injury[13] curtailed her dreams of becoming a concert violinist, but by 1922 she had her first job, playing violin in a pit orchestra for silent films at a Berlin cinema. She was fired after only four weeks.[14]

The earliest professional stage appearances by Dietrich were as a chorus girl on tour with Guido Thielscher's Girl-Kabarett vaudeville-style entertainments, and in Rudolf Nelson revues in Berlin.[15] In 1922, Dietrich auditioned unsuccessfully for theatrical director and impresario Max Reinhardt's drama academy;[16] however, she soon found herself working in his theatres as a chorus girl and playing small roles in dramas.

Career beginnings

Dietrich's film debut was a small part in the film The Little Napoleon (1923).[17] She met her future husband, Rudolf Sieber, on the set of Tragedy of Love in 1923. Dietrich and Sieber were married in a civil ceremony in Berlin on 17 May 1923.[18] Her only child, daughter Maria Elisabeth Sieber, was born on 13 December 1924.[19]

Dietrich continued to work on stage and in film both in Berlin and Vienna throughout the 1920s. On stage, she had roles of varying importance in Frank Wedekind's Pandora's Box,[20] William Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew,[20] and A Midsummer Night's Dream,[21] as well as George Bernard Shaw's Back to Methuselah[22] and Misalliance.[23] It was in musicals and revues such as Broadway, Es Liegt in der Luft, and Zwei Krawatten, however, that she attracted the most attention. By the late 1920s, Dietrich was also playing sizable parts on screen, including roles in Café Elektric (1927), I Kiss Your Hand, Madame (1928), and The Ship of Lost Souls (1929).[24]

Career

Association with von Sternberg

_by_Don_English.png)

In 1929, Dietrich landed her breakthrough role of Lola Lola, a cabaret singer who caused the downfall of a hitherto respectable schoolmaster (played by Emil Jannings), in the UFA production of The Blue Angel (1930), shot at Babelsberg film studios.[25][26] Josef von Sternberg directed the film and thereafter took credit for having "discovered" Dietrich. The film introduced Dietrich's signature song "Falling in Love Again", which she recorded for Electrola and later made further recordings in the 1930s for Polydor and Decca Records.

In 1930, on the strength of The Blue Angel's international success, and with encouragement and promotion from Josef von Sternberg, who was established in Hollywood, Dietrich moved to the United States under contract to Paramount Pictures, the U.S. film distributor of The Blue Angel. The studio sought to market Dietrich as a German answer to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's Swedish star, Greta Garbo. Sternberg welcomed her with gifts, including a green Rolls-Royce Phantom II. The car later appeared in their first U.S. film Morocco.[27]

Dietrich starred in six films directed by von Sternberg at Paramount between 1930 and 1935. Von Sternberg worked effectively with Dietrich to create the image of a glamorous and mysterious femme fatale. He encouraged her to lose weight and coached her intensively as an actress. She willingly followed his sometimes imperious direction in a way that a number of other performers resisted.[28]

In Morocco (1930), Dietrich was again cast as a cabaret singer. The film is best remembered for the sequence in which she performs a song dressed in a man's white tie and kisses another woman, both provocative for the era. The film earned Dietrich her only Academy Award nomination.

Morocco was followed by Dishonored (1931), a major success with Dietrich cast as a Mata Hari-like spy. Shanghai Express (1932), which was dubbed by the critics "Grand Hotel on wheels", was von Sternberg and Dietrich's biggest box office success, becoming the highest-grossing film of 1932. Dietrich and von Sternberg again collaborated on the romance Blonde Venus (1932). Dietrich worked without von Sternberg for the first time in three years in the romantic drama Song of Songs (1933), playing a naive German peasant, under the direction of Rouben Mamoulian. Dietrich and Sternberg's last two films, The Scarlet Empress (1934), and The Devil Is a Woman (1935)—the most stylized of their collaborations—were their lowest-grossing films. Dietrich later remarked that she was at her most beautiful in The Devil Is a Woman.

Von Sternberg is known for his exceptional skill in lighting and photographing Dietrich to optimum effect. He had a signature use of light and shadow, including the impact of light passed through a veil or slatted window blinds (as for example in Shanghai Express). This combined with the scrupulous attention to set design and costumes makes the films they made together among cinema's most visually stylish.[29] Critics still vigorously debate how much of the credit belonged to von Sternberg and how much to Dietrich, but most would agree that neither consistently reached such heights again after Paramount fired von Sternberg and the two ceased working together.[30] The collaboration of one actress and director creating seven films is still unmatched in motion pictures, with the possible exception of Katharine Hepburn and George Cukor, who made ten films together over a much longer period but which were not created for Hepburn the way the last six von Sternberg/Dietrich collaborations were.[31][32]

The later 1930s

Dietrich's first film after the end of her partnership with von Sternberg was Frank Borzage's Desire (1936), a commercial success that gave Dietrich an opportunity to try her hand at romantic comedy. Her next project, I Loved a Soldier (1936), ended in shambles when the film was scrapped several weeks into production due to script problems, scheduling confusion and the studio's decision to fire the producer Ernst Lubitsch .[33]

Extravagant offers lured Dietrich away from Paramount to make her first color film The Garden of Allah (1936) for independent producer David O. Selznick, for which she received $200,000, and to Britain for Alexander Korda's production, Knight Without Armour (1937), at a salary of $450,000, which made her one of the best paid film stars of the time. While both films performed decently at the box office, her vehicles were costly to produce and her public popularity had declined. By this time, Dietrich placed 126th in box office rankings, and American film exhibitors proclaimed her "box office poison" in May 1938, a distinction she shared with Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Mae West, Katharine Hepburn, Norma Shearer, Dolores del Río and Fred Astaire among others.[34]

While in London, Dietrich later said in interviews, she was approached by Nazi Party officials and offered lucrative contracts, should she agree to return to Germany as a foremost film star in the Third Reich. She refused their offers and applied for U.S. citizenship in 1937.[35] She returned to Paramount to make Angel (1937), another romantic comedy directed by Ernst Lubitsch; the film was poorly received, leading Paramount to buy out the remainder of Dietrich's contract.

Dietrich, with encouragement from Josef von Sternberg, accepted producer Joe Pasternak's offer to play against type in her first film in two years: that of the cowboy saloon girl, Frenchie, in the western-comedy Destry Rides Again (1939), with James Stewart. This was a significantly less well paid role than she had been accustomed. The bawdy role revived her career and "See What the Boys in the Back Room Will Have", a song she introduced in the film, became a hit when she recorded it for Decca. She played similar types in Seven Sinners (1940) and The Spoilers (1942), both with John Wayne.

World War II

Dietrich was known to have strong political convictions and the mind to speak them. In the late 1930s, Dietrich created a fund with Billy Wilder and several other exiles to help Jews and dissidents escape from Germany. In 1937, her entire salary for Knight Without Armor ($450,000) was put into escrow to help the refugees. In 1939, she became an American citizen and renounced her German citizenship.[1] In December 1941, the U.S. entered World War II, and Dietrich became one of the first public figures to help sell war bonds. She toured the U.S. from January 1942 to September 1943 (appearing before 250,000 troops on the Pacific Coast leg of her tour alone) and was reported to have sold more war bonds than any other star.[36][37]

During two extended tours for the USO in 1944 and 1945,[36] she performed for Allied troops in Algeria, Italy, the UK, France, and Heerlen in the Netherlands,[38] then entered Germany with Generals James M. Gavin and George S. Patton. When asked why she had done this, in spite of the obvious danger of being within a few kilometers of German lines, she replied, "aus Anstand"—"out of decency".[39] Wilder later remarked that she was at the front lines more than Eisenhower. Her revue, with Danny Thomas as her opening act for the first tour, included songs from her films, performances on her musical saw (a skill taught to her by Igo Sym that she had originally acquired for stage appearances in Berlin in the 1920s) and a "mindreading" act that her friend Orson Welles had taught her for his Mercury Wonder Show. Dietrich would inform the audience that she could read minds and ask them to concentrate on whatever came into their minds. Then she would walk over to a soldier and earnestly tell him, "Oh, think of something else. I can't possibly talk about that!" American church papers reportedly published stories complaining about this part of Dietrich's act.[32][36]

In 1944, the Morale Operations Branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) initiated the Musak project, musical propaganda broadcasts designed to demoralize enemy soldiers.[40] Dietrich, the only performer who was made aware that her recordings would be for OSS use, recorded a number of songs in German for the project, including "Lili Marleen", a favorite of soldiers on both sides of the conflict.[41] Major General William J. Donovan, head of the OSS, wrote to Dietrich, "I am personally deeply grateful for your generosity in making these recordings for us."[42]

At the war's end in Europe, Dietrich reunited with her sister Elisabeth and her sister's husband and son. They had resided in the German city of Belsen throughout the war years, running a cinema frequented by Nazi officers and officials who oversaw the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Dietrich's mother remained in Berlin during the war; her husband moved to a ranch in the San Fernando Valley of California. Dietrich vouched for her sister and her sister's husband, sheltering them from possible prosecution as Nazi collaborators.[43] Dietrich would later omit the existence of her sister and her sister's son from all accounts of her life, completely disowning them and claiming to be an only child.[44]

Dietrich received the Medal of Freedom in November 1947, for her "extraordinary record entertaining troops overseas during the war".[45] She said this was her proudest accomplishment.[40] She was also awarded the Légion d'honneur by the French government for her wartime work.[46]

Later film career

While Dietrich never fully regained her former screen profile, she continued performing in motion pictures, including appearances for directors such as Mitchell Leisen in Golden Earrings (1947), Billy Wilder in A Foreign Affair (1948) and Alfred Hitchcock in Stage Fright (1950). Her appearances in the 1950s, included films such as Fritz Lang's Rancho Notorious, (1952) and Wilder's Witness for the Prosecution (1957). She appeared in Orson Welles's Touch of Evil (1958). Dietrich had a kind of platonic love for Welles, whom she considered a genius.[47] Her last substantial film role was in Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) directed by Stanley Kramer; she also presented the narrative for the documentary Black Fox: The Rise and Fall of Adolf Hitler which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1962.[48] She cut the ceremonial ribbon to celebrate the grand opening of the Paris Theater in New York City in 1948.[49]

Stage and cabaret

.jpg)

From the early 1950s until the mid-1970s, Dietrich worked almost exclusively as a cabaret artist, performing live in large theatres in major cities worldwide.

In 1953, Dietrich was offered a then-substantial $30,000 per week[50] to appear live at the Sahara Hotel[51] on the Las Vegas Strip. The show was short, consisting only of a few songs associated with her.[51] Her daringly sheer "nude dress"—a heavily beaded evening gown of silk soufflé, which gave the illusion of transparency—designed by Jean Louis, attracted a lot of publicity.[51] This engagement was so successful that she was signed to appear at the Café de Paris in London the following year; her Las Vegas contracts were also renewed.[52]

Dietrich employed Burt Bacharach as her musical arranger starting in the mid-1950s; together, they refined her nightclub act into a more ambitious theatrical one-woman show with an expanded repertoire.[53] Her repertoire included songs from her films as well as popular songs of the day. Bacharach's arrangements helped to disguise Dietrich's limited vocal range—she was a contralto[54]—and allowed her to perform her songs to maximum dramatic effect;[53] together, they recorded four albums and several singles between 1957 and 1964.[55] In a TV interview in 1971, she credited Bacharach with giving her the "inspiration" to perform during those years.[56]

Bacharach then felt he needed to devote his full-time to songwriting. But she had also come to rely on him in order to perform, and wrote about his leaving in her memoir:

From that fateful day on, I have worked like a robot, trying to recapture the wonderful woman he helped make out of me. I even succeeded in this effort for years, because I always thought of him, always longed for him, always looked for him in the wings, and always fought against self-pity ... He had become so indispensable to me that, without him, I no longer took much joy in singing. When he left me, I felt like giving everything up. I had lost my director, my support, my teacher, my maestro.[57]

She would often perform the first part of her show in one of her body-hugging dresses and a swansdown coat, and change to top hat and tails for the second half of the performance.[58] This allowed her to sing songs usually associated with male singers, like "One for My Baby" and "I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face".[53]

"She ... transcends her material," according to Peter Bogdanovich. "Whether it's a flighty old tune like 'I Can't Give You Anything But Love, Baby' ... a schmaltzy German love song, 'Das Lied ist Aus' or a French one 'La Vie en Rose', she lends each an air of the aristocrat, yet she never patronises ... A folk song, 'Go 'Way From My Window' has never been sung with such passion, and in her hands 'Where Have All the Flowers Gone?' is not just another anti-war lament but a tragic accusation against us all."[59]

Francis Wyndham offered a more critical appraisal of the phenomenon of Dietrich in concert. He wrote in 1964: "What she does is neither difficult nor diverting, but the fact that she does it at all fills the onlookers with wonder ... It takes two to make a conjuring trick: the illusionist's sleight of hand and the stooge's desire to be deceived. To these necessary elements (her own technical competence and her audience's sentimentality) Marlene Dietrich adds a third—the mysterious force of her belief in her own magic. Those who find themselves unable to share this belief tend to blame themselves rather than her."[60]

Her use of body-sculpting undergarments, nonsurgical temporary facelifts (tape),[61] expert makeup and wigs,[62] combined with careful stage lighting,[52] helped to preserve Dietrich's glamorous image as she grew older.

_(Cropped).png)

Dietrich's return to West Germany in 1960 for a concert tour was met with mixed reception— despite a consistently negative press, vociferous protest by chauvinistic Germans who felt she had betrayed her homeland, and two bomb threats, her performance attracted huge crowds. During her performances at Berlin's Titania Palast theatre, protesters chanted, "Marlene Go Home!"[63] On the other hand, Dietrich was warmly welcomed by other Germans, including Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt, who was, like Dietrich, an opponent of the Nazis who had lived in exile during their rule.[63] The tour was an artistic triumph, but a financial failure.[63] She was left emotionally drained by the hostility she encountered, and she left convinced never to visit again. East Germany, however, received her well.[64] She also undertook a tour of Israel around the same time, which was well-received; she sang some songs in German during her concerts, including, from 1962, a German version of Pete Seeger's anti-war anthem "Where Have All the Flowers Gone", thus breaking the unofficial taboo against the use of German in Israel.[62] She would become the first woman and German to receive the Israeli Medallion of Valor in 1965, "in recognition for her courageous adherence to principle and consistent record of friendship for the Jewish people". Dietrich in London, a concert album, was recorded during the run of her 1964 engagement at the Queen's Theatre.[65]

She performed on Broadway twice (in 1967 and 1968) and won a special Tony Award in 1968. In November 1972, I Wish You Love, a version of Dietrich's Broadway show titled An Evening with Marlene Dietrich, was filmed in London.[66] She was paid $250,000 for her cooperation but was unhappy with the result. The show was broadcast in the UK on the BBC and in the U.S. on CBS in January 1973.[67]

Dietrich continued with a busy performance schedule until September 1975.[68] When asked about why she continued to perform by Clive Hirschhorn she said, "Do you think this is glamorous? That this is a great life, and that I do it for my health? Well, it isn't. It's hard work. And who would work if they didn't have to?"[69]

In her 60s and 70s, Dietrich's health declined: she survived cervical cancer in 1965[70] and suffered from poor circulation in her legs.[62] Dietrich became increasingly dependent on painkillers and alcohol.[62] A stage fall at the Shady Grove Music Fair in Maryland in 1973 injured her left thigh, necessitating skin grafts to allow the wound to heal.[71] She fractured her right leg in August 1974.[72]

Paris years

Dietrich's show business career largely ended on 29 September 1975, when she fell from the stage and broke a thigh bone during a performance in Sydney, Australia.[73] The following year, her husband, Rudolf Sieber, died of cancer on 24 June 1976.[74] Dietrich's final on-camera film appearance was a brief appearance in Just a Gigolo (1979), starring David Bowie and directed by David Hemmings, in which she sang the title song.

Dietrich withdrew to her apartment at 12 Avenue Montaigne in Paris. She spent the final 13 years of her life mostly bedridden, allowing only a select few—including family and employees—to enter the apartment. During this time, she was a prolific letter-writer and phone-caller. Her autobiography Nehmt nur mein Leben (Take Just My Life), was published in 1979.[75]

In 1982, Dietrich agreed to participate in a documentary film about her life, Marlene (1984), but refused to be filmed. The film's director, Maximilian Schell, was allowed only to record her voice. Schell used his interviews with her as the basis for the film, set to a collage of film clips from her career. The film won several European film prizes and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary in 1984. Newsweek named it "a unique film, perhaps the most fascinating and affecting documentary ever made about a great movie star".[76]

In 1988, Dietrich recorded spoken introductions to songs for a nostalgia album by Udo Lindenberg.[77]

In an interview with the German magazine Der Spiegel in November 2005, Dietrich's daughter and grandson said Dietrich was politically active during these years.[78] She kept in contact with world leaders by telephone, including Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, running up a monthly bill of over US$3,000. In 1989, her appeal to save the Babelsberg Studios from closure was broadcast on BBC Radio, and she spoke on television via telephone on the occasion of the fall of the Berlin Wall later that year.

Death and estate

On 6 May 1992, Dietrich died of kidney failure at her flat in Paris at age 90. Her funeral was a requiem mass conducted at the Roman Catholic church of La Madeleine in Paris on 14 May 1992.[79] Dietrich's funeral service was attended by approximately 1,500 mourners in the church itself—including several ambassadors from Germany, Russia, the US, the UK and other countries—with thousands more outside. Her closed coffin, draped in the French flag, rested beneath the altar and was adorned with a simple bouquet of white wildflowers and roses from the French President François Mitterrand. Three medals, including France's Legion of Honour and the U.S. Medal of Freedom, were displayed at the foot of the coffin, military style, for a ceremony symbolising the sense of duty Dietrich embodied in her career as an actress, and in her personal fight against Nazism. The officiating priest remarked: "Everyone knew her life as an artist of film and song, and everyone knew her tough stands ... She lived like a soldier and would like to be buried like a soldier".[80][81] By coincidence, her picture was used in the Cannes Film Festival poster that year which was pasted up all over Paris.[82]

In her will Dietrich expressed the wish to be buried in her birthplace Berlin, near her family. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall her body was flown there to fulfill her wish on 16 May .[83] Her coffin was draped in an American flag befitting her status as an American. As her coffin traveled through Berlin bystanders threw flowers onto it, a fitting tribute because Dietrich loved flowers, even saving the flowers thrown to her at the end of her performances for use in subsequent shows. Dietrich was interred at the Städtischer Friedhof III, Schöneberg, close by the grave of her mother Josefine von Losch, and near the house where she was born.[80]

On 24 October 1993, the largest portion of Dietrich's estate was sold to the Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek—after U.S. institutions showed no interest—where it became the core of the exhibition at the Filmmuseum Berlin. The collection includes: over 3,000 textile items from the 1920s to the 1990s, including film and stage costumes as well as over a thousand items from Dietrich's personal wardrobe; 15,000 photographs, by Sir Cecil Beaton, Horst P. Horst, George Hurrell, Lord Snowdon and Edward Steichen; 300,000 pages of documents, including correspondence with Burt Bacharach, Yul Brynner, Maurice Chevalier, Noël Coward, Jean Gabin, Ernest Hemingway, Karl Lagerfeld, Nancy and Ronald Reagan, Erich Maria Remarque, Josef von Sternberg, Orson Welles and Billy Wilder; as well as other items like film posters and sound recordings.[84] The Marlene Dietrich Collection was sold to the Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek for US$5 million, by Dietrich's heirs.[85]

The contents of Dietrich's Manhattan apartment, along with other personal effects such as jewelry and items of clothing, were sold by public auction by Sotheby's in Los Angeles in November 1997. Her former apartment located at 993 Park Avenue was sold for $615,000 in 1998.[86]

Personal life

Unlike her professional celebrity, which was carefully crafted and maintained, Dietrich's personal life was, for the most part, kept out of public view. She was fluent in German, English, and French. Dietrich, who was bisexual, enjoyed the thriving gay bars and drag balls of 1920s Berlin.[87][88] She also defied conventional gender roles through her boxing at Turkish trainer and prizefighter Sabri Mahir's boxing studio in Berlin, which opened to women in the late 1920s. Dietrich married only once, to assistant director Rudolf Sieber, who later became an assistant director at Paramount Pictures in France, responsible for foreign language dubbing. Dietrich's only child, Maria Riva, was born in Berlin on 13 December 1924. She would later become an actress, primarily working in television. When Maria gave birth to a son (John, later a famous production designer) in 1948, Dietrich was dubbed "the world's most glamorous grandmother". After Dietrich's death, Riva published a candid biography of her mother, titled Marlene Dietrich (1992).

Throughout her career, Dietrich had numerous affairs, some short-lived, some lasting decades, often overlapping and almost all known to her husband, to whom she was in the habit of passing the intimate letters from her lovers, sometimes with biting comments.[89] When Dietrich arrived in Hollywood and filmed Morocco (1930), she had an affair with Gary Cooper, even though he was having another affair with Mexican actress Lupe Vélez.[90] Vélez once said, "If I had the opportunity to do so, I would tear out Marlene Dietrich's eyes."[91] Another of her affairs was with actor John Gilbert, known for his professional and personal connection to Greta Garbo. Gilbert's untimely death was one of the most painful events of her life.[92] Dietrich also had a brief affair with Douglas Fairbanks Jr., even though he had been married to Joan Crawford.[93] During the production of Destry Rides Again, Dietrich started a love affair with co-star James Stewart, which ended after filming stopped. In 1938, Dietrich met and began a relationship with writer Erich Maria Remarque, and in 1941, the French actor Jean Gabin. The relationship ended in 1948.[94]

In the early 1940s, Dietrich had an affair with Cuban-American writer Mercedes de Acosta, who claimed to be Greta Garbo's lover. Sewing circle was a phrase used by Dietrich[95] to describe the underground, closeted lesbian and bisexual film actresses and their relationships in Hollywood. In the supposed "Marlene's Sewing Circle" [96] are mentioned the names of other close friends such as Ann Warner (the wife of Jack L. Warner, one of the owners of the Warner studios), Lili Damita (an old friend of Marlene's from Berlin and the wife of Errol Flynn), Claudette Colbert,[97] and Dolores del Río (whom Dietrich considered the most beautiful woman in Hollywood).[98][99] The French singer Edith Piaf was also one of Dietrich's closest friends during her stay in Paris in the 1950s, and there were rumors of something more than friendship between them.[100][101]

When Dietrich was in her 50s, she had a relationship with actor Yul Brynner, which lasted more than a decade. Dietrich's love life continued into her 70s. She counted Errol Flynn,[102] George Bernard Shaw, John F. Kennedy, Joe Kennedy, Michael Todd, Michael Wilding, John Wayne, Kirk Douglas, and Frank Sinatra among her conquests.[103] Dietrich maintained her husband and his mistress first in Europe and later on a ranch in the San Fernando Valley, near Hollywood.[104]

Dietrich was raised in the German Lutheran tradition of Christianity, but she abandoned it as a result of her experiences as a teenager during World War I, after hearing preachers from both sides invoking God as their support. "I lost my faith during the war and can't believe they are all up there, flying around or sitting at tables, all those I've lost."[105] Quoting Goethe in her autobiography, she wrote, "If God created this world, he should review his plan."

Legacy

Dietrich was an icon to fashion designers and screen stars. Edith Head remarked that Dietrich knew more about fashion than any other actress. Marlene Dietrich favoured Dior. In an interview with The Observer in 1960, she said, "I dress for the image. Not for myself, not for the public, not for fashion, not for men. If I dressed for myself I wouldn't bother at all. Clothes bore me. I'd wear jeans. I adore jeans. I get them in a public store – men's, of course; I can't wear women's trousers. But I dress for the profession." [106] In 2017, Swarovski commissioned a $60,000 Art Deco-styled dress in the style of her famous "nude dress", from Berlin-based fashion tech company ElektroCouture to honor Dietrich 25 years after her death. It contains 2,000 crystals in addition to 150 LED lights.[107] ElektroCouture owner Lisa Lang said that the dress was inspired by electrical diagrams and correspondence that took place between the actress and fashion designer Jean Louis in 1958. "She wanted a dress that glows, she wanted to be able to control it herself from the stage and she knew she could have died of an electric stroke had it ever been realized." The dress created by Lang's company was featured in French-German broadcaster Arte's documentary “Das letzte Kleid der Marlene Dietrich” ("The Last Dress of Marlene Dietrich").[108]

Her public image included openly defying sexual norms, and she was known for her androgynous film roles and her bisexuality.[109]

A significant volume of academic literature, especially since 1975, analyzes Dietrich's image, as created by the film industry, within various theoretical frameworks, including that of psycho-analysis. Emphasis is placed, inter alia, on the "fetishistic" manipulation of the female image.[110]

In 1992, a plaque was unveiled at Leberstraße 65 in Berlin-Schöneberg, the site of Dietrich's birth. A postage stamp bearing her portrait was issued in Germany on 14 August 1997.

The main-belt asteroid 1010 Marlene, discovered by German astronomer Karl Reinmuth at Heidelberg Observatory in 1923, was named in her honor.[111]

For some Germans, Dietrich remained a controversial figure for having sided with the Allies during World War II. In 1996, after some debate, it was decided not to name a street after her in Berlin-Schöneberg, her birthplace.[112] However, on 8 November 1997, the central Marlene-Dietrich-Platz was unveiled in Berlin to honour her. The commemoration reads: Berliner Weltstar des Films und des Chansons. Einsatz für Freiheit und Demokratie, für Berlin und Deutschland ("Berlin world star of film and song. Dedication to freedom and democracy, to Berlin and Germany").

Dietrich was made an honorary citizen of Berlin on 16 May 2002. Translated from German, her memorial plaque reads

Berlin Memorial Plaque

Funded by the GASAG Berlin Gasworks Corporation.

"Tell me where the flowers are"

Marlene Dietrich

27 December 1901 – 6 May 1992

Actress and Singer

She was one of the few German actresses that attained international significance.

Despite tempting offers by the Nazi regime, she emigrated to the USA and became an American citizen.

In 2002, the city of Berlin posthumously made her an honorary citizen.

"I am, thank God, a Berliner."

The U.S. Government awarded Dietrich the Medal of Freedom for her war work. Dietrich has been quoted as saying this was the honor of which she was most proud in her life. They also awarded her with the Operation Entertainment Medal. The French Government made her a Chevalier (later upgraded to Commandeur) of the Légion d'honneur and a Commandeur of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Her other awards include the Medallion of Honor of the State of Israel, the Fashion Foundation of America award and a Chevalier de l'Ordre de Leopold (Belgium).[113]

Dietrich is referenced in a number of popular 20th century songs, including Rodgers and Hart's "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World" (1935), Peter Sarstedt's "Where Do You Go To, My Lovely?" (1969), Suzanne Vega's "Marlene On The Wall" (1985), and Madonna's "Vogue" (1990).

In 2000 a German biopic film Marlene was made, directed by Joseph Vilsmaier and starring Katja Flint as Dietrich.[114]

On 27 December 2017, she was given a Google Doodle on the 116th anniversary of her birth.[115] The doodle was designed by American drag artist Sasha Velour, who cites Dietrich as a big inspiration due to her "gender-bending" fashion and political views.[116] Sasha portrayed Marlene during her time at competitive reality series RuPaul's Drag Race.

On 14 May 2020, she was part of an Entertainment Weekly cover celebrating LBGTQ celebrities.[117]

Works

Filmography

Discography

Radio

Noteworthy appearances include:

- Lux Radio Theater: The Legionnaire and the Lady with Clark Gable (1 August 1936)

- Lux Radio Theater: Desire with Herbert Marshall (22 July 1937)

- Lux Radio Theater: Song of Songs with Douglas Fairbanks, Jr (20 December 1937)

- The Chase and Sanborn Hour with Edgar Bergen and Don Ameche (2 June 1938)

- Lux Radio Theater: Manpower with Edward G Robinson and George Raft (15 March 1942)

- The Gulf Screen Guild Theater: Pittsburgh with John Wayne (12 April 1943)

- Theatre Guild on the Air: Grand Hotel with Ray Milland (24 March 1948)

- Studio One: Arabesque (29 June 1948)

- Theatre Guild on the Air: The Letter with Walter Pidgeon (3 October 1948)

- Ford Radio Theater: Madame Bovary with Claude Rains (8 October 1948)

- Screen Director's Playhouse: A Foreign Affair with Rosalind Russell and John Lund (5 March 1949)

- MGM Theatre of the Air: Anna Karenina (9 December 1949)[118]

- MGM Theatre of the Air: Camille (6 June 1950)

- Lux Radio Theater: No Highway in the Sky with James Stewart (21 April 1952)

- Screen Director's Playhouse: A Foreign Affair with Lucille Ball and John Lund (1 March 1951)

- The Big Show starring Tallulah Bankhead (2 October 1951)

- Marlene Dietrich in conversation with J.W. Lambert and Carl Wildman recorded after her season at the Queen's Theatre London, BBC radio, 12 August 1965 (a shorter version had been broadcast on 2 April).

- The Child, with Godfrey Kenton, radio play by Shirley Jenkins, produced by Richard Imison for the BBC on 18 August 1965

- Dietrich's appeal to save the Babelsberg Studio was broadcast on BBC radio

Dietrich made several appearances on Armed Forces Radio Services shows like The Army Hour and Command Performance during the war years. In 1952, she had her own series on American ABC entitled, Cafe Istanbul. During 1953–54, she starred in 38 episodes of Time for Love on CBS (which debuted 15 January 1953).[119] She recorded 94 short inserts, "Dietrich Talks on Love and Life", for NBC's Monitor in 1958. Dietrich gave many radio interviews worldwide on her concert tours. In 1960, her show at the Tuschinski in Amsterdam was broadcast live on Dutch radio. Her 1962 appearance at the Olympia in Paris was also broadcast.

- Desert Island Discs, Dietrich asked to choose eight recordings, broadcast Monday 4 January 1965

Writing

- Dietrich, Marlene (1962). Marlene Dietrich's ABC. Doubleday.

- Dietrich, Marlene (1979). Nehmt nur mein Leben: Reflexionen (in German). Goldmann. ISBN 978-3-442-06327-7.

- Dietrich, Marlene (1989). Marlene. Salvator Attanasio (translator). Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1117-3.

- Dietrich, Marlene (1990). Some Facts About Myself. Helnwein, Gottfried [Conception and photographs]. ISBN 978-3-89322-226-1.

- Dietrich, Marlene (2005). Nachtgedanken. Riva, Maria [Edited by]. ISBN 978-3-57000-874-4.

See also

- List of German-speaking Academy Award winners and nominees

- List of people from Berlin

References

Notes

- Flint, Peter B. (7 May 1992). "Marlene Dietrich, 90, Symbol of Glamour, Dies". The New York Times.

- "Marlene Dietrich to be US Citizen". Painesville Telegraph. 6 March 1937.

- "Citizen Soon". Telegraph Herald. 10 March 1939.

- "Seize Luggage of Marlene Dietrich". Lawrence Journal-World. 14 June 1939.

- "Marlene Dietrich – The Ultimate Gay Icon » The Cinema Museum, London". The Cinema Museum, London. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- "AFI's 50 Greatest American Screen Legends". American Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- Born as Maria Magdalena, not Marie Magdalene, according to Dietrich's biography by her daughter, Maria Riva (Riva 1993); however Dietrich's biography by Charlotte Chandler cites "Marie Magdalene" as her birth name (Chandler 2011, p. 12).

- Bach 2011, p. 19.

- "Marlene Dietrich (German-American actress and singer)". Our Queer History. 9 February 2016.

- Bach 1992, p. 20.

- Bach 1992, p. 26.

- Bach 1992, p. 32.

- Bach 1992, p. 39.

- Bach 1992, p. 42.

- Bach 1992, p. 44.

- Bach 1992, p. 49.

- Bach 1992, p. 491.

- Bach 2011, p. 62.

- Bach 1992, p. 65.

- Bach 1992, p. 480.

- Bach 1992, p. 482.

- Bach 1992, p. 483.

- Bach 1992, p. 488.

- "Ship of Lost Men (Das Schiff der verlorenen Menschen)". Amazon. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- "100th anniversary of Studio Babelsberg". www.studiobabelsberg.com. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- "filmportal: The Blue Angel". www.filmportal.de. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- "The Ex-Marlene Dietrich, Multiple Best in Show Winning 1930 Rolls-Royce Phantom". Bonhams. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- See e.g., Thomson (1975), p. 587: "He was not an easy man to be directed by. Many actors—notably [Emil] Jannings and William Powell—reacted violently to him. Dietrich adored him, and trusted him. ... "

- See, for example, Thomson (1975). The entry for Dietrich: "With him [von Sternberg] Dietrich made seven masterpieces [i.e., Blue Angel in Germany and the six in Hollywood], films that are still breathtakingly modern, which have no superior for their sense of artificiality suffused with emotion and which visually combine decadence and austerity, tenderness and cruelty, gaiety and despair."

- See, for example, the entries for Dietrich and Sternberg in Thomson (1975).

- Nightingale, Benedict (1 February 1979). "After Making Nine Films Together, Hepburn Can Practically Direct Cukor; Hepburn Helps Cukor Direct The Corn Is Green'". The New York Times.

- Spoto 1992.

- Bach 1992, pp. 210-211.

- "How Joan Crawford Survived Box Office Poison twice!". 29 July 2015.

- Helm, Toby (24 June 2000). "Film star felt ashamed of Belsen link". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Sudendorf, Werner.

- "Thanks Soldier". MarleneDietrich.org. 2000. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Rijckheyt - centrum voor regionale geschiedenis". www.rijckheyt.nl (in Dutch).

- "A Soldier Lovingly Remembers Marlene Dietrich". Sister Celluloid. 27 December 2014.

- "A Look Back ... Marlene Dietrich: Singing For A Cause". Central Intelligence Agency. 23 October 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- McIntosh 1998, p. 58.

- McIntosh 1998, p. 59.

- Marlene Dietrich: Her Own Song. TCM documentary. 2001.

- Helm, Toby (24 June 2000). "Film star felt ashamed of Belsen link". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Miss Dietrich to Receive Medal" (PDF). The New York Times. 18 November 1947.

- "Marlene Dietrich : Biography". Who's Who – The People Lexicon (in German). www.whoswho.de. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur and Officier de la Légion d'Honneur

- Bach 1992, p. 462.

- "NY Times: Black Fox: The Rise and Fall of Adolf Hitler". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- "Netflix to Keep New York's Paris Theatre Open". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Bach 1992, p. 369.

- Bach 1992, p. 368.

- Bach 1992, p. 371.

- Bach 1992, p. 395.

- Carpenter, Cassie (9 August 2011). "Cassie's Corner: Marlene Dietrich's Top 10 Badass One-Liners". L.A Slush. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- O'Connor 1991, p. 154.

- "Marlene Dietrich 1971 Copenhagen Interview" on YouTube, 1/2 hour video

- Dietrich, Marlene. Marlene, Grove Press (1989) ebook

- Bach 1992, p. 394.

- Morley 1978, p. 69.

- O'Connor 1991, p. 133.

- "How one night in Montreal changed the life of Marlene Dietrich". Montreal Gazette. 2 May 2012.

- Bach 1992, p. 406.

- Bach 1992, p. 401.

- Chesnoff, Richard Z. (7 March 1966). "A Candid Portrait of Marlene Dietrich". Montreal Gazette.

- Bach 1992, p. 526.

- "I Wish You Love Production Schedule". Marlene Dietrich Collection Berlin. Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- Roberts, Paul G. Style Icons Vol 4 Sirens. Fashion Industry Broadcast, 2015 p. 39.

- "Marlene Dietrich Concert Setlists". setlist.fm. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- "Marlene Dietrich". IMDb. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Bach 1992, p. 416.

- Bach 1992, p. 436.

- Bach 1992, p. 437.

- "Act follows suggestion of song's title". Toledo Blade. Ohio. 7 November 1973. p. 37.

- Voss, Joan. "Marlene Dietrich". Senior Connection. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- "Nehmt nur mein Leben ... : Reflexionen / Marlene Dietrich". Library of Congress Online Catalogue. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Marlene". Atlas International. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- Bach 1992, p. 528.

- "Der Himmel war grün, wenn sie es sagte". Der Spiegel (in German). 13 November 2005.

- "I have given up belief in a God." Allen Smith, Warren (2002). Celebrities in Hell: A Guide to Hollywood's Atheists, Agnostics, Skeptics, Free Thinkers, and More. Barricade Books Inc. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-56980-214-4.

- "Obituary of Maria Magdalene "Marlene" Dietrich". The Message Newsjournal. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- "Marlene Dietrich Funeral". Associated Press Images. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- "15 Most Inspiring Cannes Film Festival Posters". Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "Obituary for Marlene Magdelene Dietrich". The Message Newsjournal. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- "Marlene Dietrich: Berlin". Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- Reif, Rita (15 September 1993). "Berlin Buys Collection of Dietrich Memorabilia". The New York Times.

- Swanson, Carl (5 April 1998). "Recent Transactions in the Real Estate Market". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- Bourke, Amy (29 May 2007). "Bisexual side of Dietrich show". Pink News. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- Kennison, Rebecca (2002). "Clothes Make the (Wo)man: Marlene Dietrich and "Double Drag"". Journal of Lesbian Studies. 6 (2): 147–156. doi:10.1300/J155v06n02_19. PMID 24807670.

- Riva 1994, p. 344.

- "History on Film: Actors: Gary Cooper". Archived from the original on 11 February 2012.

- "Marlene Dietrich". Revista Vanidades de México. 46 (12): 141. 2006. ISSN 1665-7519.

- Bach 1992, pp. 207, 211.

- Bach 1992, p. 223.

- "Marlene Dietrich und Jean Gabin - Ein ungleiches Liebespaar". Archived.

- Freeman, David (7 January 2001). "Closet Hollywood: A gossip columnist discloses some secrets about movie idols". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- Madsen, Axel (2002). The Sewing Circle: Sappho's Leading Ladies. New York: Kensington Books. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7582-0101-0.

- Moser, Margaret (2011). Movie Stars Do the Dumbest Things. Macmillan. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4299-7837-8.

- Bach 1992, p. 240.

- Riva 1994, pp. 489, 675.

- Bach 1992, pp. 316, 380.

-

Carly Maga (17 September 2019). "Edith Piaf, 'the kind of women everybody's trying to be right now'". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

The latter was notably present at Piaf’s 1952 wedding to singer Jacques Pills, but the women’s relationship began in the 1940s as Piaf was first trying to break into American entertainment and Dietrich took the sparrow under her wing, so to speak.

- McNulty, Thomas (2004). Errol Flynn: The Life and Career. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1750-6.

- Riva 1994, passim.

- Riva, Maria. Marlene Dietrich.

- Bach 2011.

- "From the Observer archive, 6 March 1960: Marlene Dietrich's wardrobe secrets". The Guardian. 4 March 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Knowles, Kitty (1 May 2018). "ElektroCouture: Inside The Fashion House Behind Swarovski's $60,000 Light-Up Dress". Forbes. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- Tran, Quynh (10 April 2017). "Marlene Dietrich's Fashion Tech Vision". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- Gammel 2012, p. 373.

- Weber, Caroline (September–November 2007). "Academy Award: A new volume analyzes Dietrich in and out of the seminar room". Bookforum.

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). "(1010) Marlene". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – (1010) Marlene. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 87. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_1011. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- "The German-Hollywood Connection: Dietrich's Street". Archived from the original on 22 December 2008.

- "The Legendary, Lovely Marlene". marlenedietrich.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Rentschler, Eric (2007). "An Icon between the Fronts". In Schindler, Stephan K; Koepnick, Lutz Peter (eds.). The Cosmopolitan Screen: German Cinema and the Global Imaginary, 1945 to the present. University of Michigan Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-472-06966-8.

- "Marlene Dietrich: Why Google honours her today". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "Marlene Dietrich's 116th Birthday". Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Pride Forever: EW's LGBTQ issue celebrates new storytellers, enduring icons, and Hollywood history". www.ew.com. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Morse, Leon (22 October 1949). "The MGM Theater of the Air". Billboard. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- Kirby, Walter (11 January 1953). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. p. 42. Retrieved 19 June 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

Sources

- Bach, Steven (1992). Marlene Dietrich: Life and Legend. William Morrow and Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-688-07119-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bach, Steven (2011). Marlene Dietrich: Life and Legend. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-7584-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chandler, Charlotte (2011). Marlene Dietrich, a personal biography. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-8835-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gammel, Irene (2012). "Lacing up the Gloves: Women, Boxing and Modernity". Cultural and Social History. 9 (3): 369–390. doi:10.2752/147800412X13347542916620.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McIntosh, Elizabeth P. (1998). Sisterhood of Spies: The Women of the OSS. London: Dell. ISBN 978-0-440-23466-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morley, Sheridan (1978). Marlene Dietrich. Sphere Books. ISBN 978-0-7221-6163-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Connor, Patrick (1991). The Amazing Blonde Woman: Dietrich's Own Style. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-1264-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riva, Maria (1993). Marlene Dietrich (1st ed.). Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-58692-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riva, Maria (1994). Marlene Dietrich. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-38645-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spoto, Donald (1992). Blue Angel: The Life of Marlene Dietrich. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-42553-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomson, David (1975). A Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema. London: Secker and Warburg. ISBN 978-0-436-52010-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Carr, Larry (1970). Four Fabulous Faces:The Evolution and Metamorphosis of Swanson, Garbo, Crawford and Dietrich. Doubleday and Company. ISBN 978-0-87000-108-6.

- Riva, David J. (2006). A Woman at War: Marlene Dietrich Remembered. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-3249-8.

- Walker, Alexander (1984). Dietrich. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-015319-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marlene Dietrich. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Marlene Dietrich |

- Official website

- Marlene Dietrich at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Marlene Dietrich at the Internet Broadway Database

- Marlene Dietrich on IMDb

- Marlene Dietrich at AllMovie

- Marlene Dietrich at the TCM Movie Database

- Marlene Dietrich Collection, Berlin (MDCB)

- Marlene Dietrich – Daily Telegraph obituary

- A film clip Air Army Invades Germany (1945) is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip Atom Test Nears, 1946/06/13 (1946) is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip Cruiser Bow Ripped Off By Typhoon, 1945/07/23 (1945) is available at the Internet Archive

- A Soldier Lovingly Remembers Marlene Dietrich

- Marlene Dietrich FBI Files

- Spring, Kelly. "Marlene Dietrich". National Women's History Museum. 2017.