Presidio County, Texas

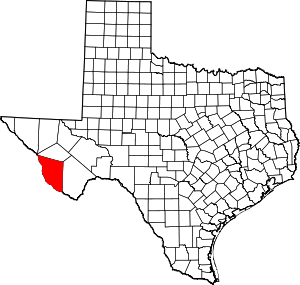

Presidio County is a county located in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2010 census, its population was 7,818.[1] Its county seat is Marfa.[2] The county was created in 1850 and later organized in 1875.[3] Presidio County (K-5 in Texas topological index of counties) is in the Trans-Pecos region of West Texas and is named for the ancient border settlement of Presidio del Norte. It is on the Rio Grande, which forms the Mexican border.

Presidio County | |

|---|---|

Presidio County Courthouse in Marfa | |

Location within the U.S. state of Texas | |

Texas's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 30°00′N 104°14′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1875 |

| Seat | Marfa |

| Largest city | Presidio |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,856 sq mi (9,990 km2) |

| • Land | 3,855 sq mi (9,980 km2) |

| • Water | 0.7 sq mi (2 km2) 0.02%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2015) | 6,876 |

| • Density | 2.0/sq mi (0.8/km2) |

| Congressional district | 23rd |

| Website | www |

History

Native Americans

Paleo-Indians (hunter-gatherers) existed thousands of years ago on the Trans-Pecos, and often did not adapt to culture clashes, European diseases, and colonization. The Masames tribe was exterminated by the Tobosos, circa 1652.[4] The Nonojes suffered from clashes with the Spanish and merged with the Tobosos. The Spanish made slave raids to the La Junta de los Ríos, committing cruelties against the native population.[5] The Suma-Jumano tribe sought to align themselves with the Spanish for survival. The tribe later merged with the Apache people. Foraging peoples who did not survive the 18th century include the Chisos, Mansos, Jumanos, Conchos, Julimes, Cibolos, Tobosos, Sumas, Cholomes, Caguates, Nonojes, Cocoyames, and Acoclames.[6]

Early explorations and settlements

The entrada of Juan Domínguez de Mendoza[7] and Father Nicolás López[8] in 1683–84 set out from El Paso to La Junta, where they established seven missions at seven pueblos. In 1683, Father López celebrated the first Christmas Mass in Texas at La Junta.

In 1832, José Ygnacio Ronquillo was issued a conditional land grant, and established the county’s first white settlement on Cibolo Creek. Military obligations forced him to abandon the settlement, and he then sold the land.[9]

The Chihuahua Trail connecting Mexico’s state of Chihuahua with Santa Fe, New Mexico, opened in 1839.[10][11]

By 1848, Ben Leaton built Fort Leaton, sometimes called the largest adobe structure in Texas, on the river as his home, trading post, and private bastion. Leaton died in debt in 1851, with the fort passing to the holder of the mortgage, John Burgess. In 1934, T. C. Mitchell and the Marfa State Bank acquired the old structure and donated it to the county as a historic site. The park was opened to the public in 1978.[12][13][14]

Milton Faver became the county’s first cattle baron.[15] In 1857, he moved his family to Chinati Mountains in the county. Faver bought small tracts of land around three springs-Cibolo, Cienega, and La Morita and established cattle ranches. He built Fort Cienega and Fort Cibolo.[16]

County established and growth

Presidio County was established from Bexar County on January 3, 1850. Fort Leaton became the county seat. The county was organized in 1875 as the largest county in the United States, with 12,000 square miles (31,000 km2). Fort Davis was named the county seat. The boundaries and seat of Presidio County were changed in the 1880s. Marfa was established in 1883, and the county seat was moved there from Fort Davis in 1885.[17]

In 1854, the army built Fort Davis in northern Presidio County.[18] Fort Davis closed during the Civil War and reopened in 1867. The black population increased to 489 when Buffalo Soldiers were stationed at Fort Davis.[19][20]

John W. Spencer, a local rancher and trader, found a silver deposit in the Chinati Mountains in 1880 that resulted in the opening of Presidio Mine and the beginning of the company town of Shafter.[21] From 1883 until 1942, the mine produced over 32.6 million ounces of silver.[22]

The railroad reached Presidio County in 1882, when the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway laid tracks through its northeastern corner.[23]

W. F. Mitchell built the first barbed wire fence in the county at Antelope Springs in 1888. The widespread use of barbed wire resulted in the refinement of cattle breeds, improvement of ranges, and innovative use of water supplies.[23]

Windmills, water wells, and earthen tanks were introduced on Presidio County ranches in the late 1880s.[24]

Elephant Butte Dam was built in 1910 on the Rio Grande, creating a large, reliable irrigation source for the county.[25][26]

The growth of Presidio County's population in the 1910s reflected the impact of the Mexican Revolution on border life. Refugees migrated to the county from Chihuahua as the fighting moved into northern Mexico. The United States Army established several posts in the county. Marfa became the headquarters for the Big Bend Military District, and in 1917, the Army established Camp Marfa, later called Fort D. A. Russell, at Marfa to protect the border.[27] As Presidio County entered the 1930s the people faced a drought and a population decline. Low silver prices closed Presidio Mine at Shafter. Economic recovery began by 1936. During World War II, Presidio County enjoyed economic prosperity as the home for two military installations-Fort Russell and Marfa Army Airfield.[28][29]

In late January 1918, during a period of tension between the US and Mexico, Texas Rangers and citizens of the village of Porvenir murdered 15 local Hispanic residents.[30]

The economy of the county in 1982 was based primarily on agriculture, with 83% of the land in farms and ranches.[23]

Marfa Lights

Wagon trains on the Chihuahua Trail reported seeing unexplained lights in the mid-19th century.[31][32][33] The first recorded incident of the Marfa Lights was in 1883 when Robert Reed Ellison and cowhands camped at Mitchell Flats.[34][35] They thought the lights might have been Apaches, but later found no evidence of an Apache encampment. Since that time, the lights continue to appear between Marfa and Paisano Pass. Speculation and fascination spark imaginations about the source. Some say they are caused by car headlights; some say extraterrestrial visitors. One theory is that the lights are similar to a mirage caused by atmospheric conditions. Marfa celebrates with a Mystery Lights Festival every Labor Day.[36]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 3,856 square miles (9,990 km2), of which 3,855 square miles (9,980 km2) are land and 0.7 square miles (1.8 km2) (0.02%) is covered by water.[37] It is the fourth-largest county in Texas by area.

Presidio County is triangular in shape and is bounded on the east by Brewster County, on the north by Jeff Davis County, and on the south and west for 135 miles (217 km) by the Rio Grande and Mexico. Marfa, the county seat, is 190 miles (306 km) southeast of El Paso and 150 miles (241 km) southwest of Odessa. The center of the county lies at 30°30' north latitude and 104°15' west longitude.

Geographically, Presidio County comprises 3,857 square miles (9,990 km2) of contrasting topography, geology, and vegetation. In the north and west, clay and sandy loam cover the rolling plains known as the Marfa Plateau and the Highland Country, providing good ranges of grama grasses for the widely acclaimed Highland Herefords. In the central, far western, and southeastern areas of the county, some of the highest mountain ranges in Texas are found. These peaks are formed of volcanic rock and covered with loose surface rubble. They support desert shrubs and cacti and dominate a landscape of rugged canyons and numerous springs. The spring-fed Capote Falls, with a drop of 175 feet (53 m), the highest in Texas, is located in western Presidio County. In the southern and western parts of the county, the volcanic cliffs of the Candelaria Rimrock (also called the Sierra Vieja) rise perpendicular and run parallel to the river, separating the highland prairies from the desert floor hundreds of feet below them. The gravel pediment, which allows only the growth of desert shrubs and cacti, extends from the Rimrock to the flood plain of the river. Along the river, irrigation allows the farming of vegetables, grains, and cotton. No permanent streams exist in the county, although many arroyos become raging torrents during heavy rainfalls. Major ones are Alamito Creek, Cibolo Creek, Capote Creek, and Pinto Canyon. San Esteban Dam was built across Alamito Creek and on the site of a historic spring-fed tinaja in 1911 as an irrigation and land-promotion project. Altitudes in the county vary from 2,518 to 7,728 feet (767 to 2,355 m) above sea level. Temperatures, moderated by the mountains, vary from 33 °F (1 °C) in January to 100 °F (38 °C) in July. Average rainfall is 12 inches (300 mm) per year, mainly in June, July, and August. The growing season extends for 238 days. Natural resources under production in 1982 were perlite, crushed rhyolite, sand, and gravel. Silver mining contributed greatly to the economy of the county from the 1880s to the 1940s. Presidio County has no oil or gas production.

Major highways

Adjacent counties and municipios

Presidio County's unusual shape has it facing more of Mexico than the rest of the United States. The county is bounded on the east by Brewster County, on the north by Jeff Davis County, and on the south and west for 135 miles (217 km) by the Rio Grande and Mexico. Along the international border, the county faces the Manuel Benavides and Ojinaga Districts of the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, on the south side, and the municipality of Guadalupe of the State of Chihuahua, Mexico, on its southwestern side.

- Hudspeth County (northwest)

- Jeff Davis County (north)

- Brewster County (east)

- Manuel Benavides Municipality, Chihuahua, Mexico (south)

- Ojinaga Municipality, Chihuahua, Mexico (southwest)

- Guadalupe Municipality, Chihuahua, Mexico (west)

Climate

More than half of Presidio County, 54.6%, experiences a hot arid desert climate (Köppen BWh). The remainder has a semiarid steppe climate with 34.7% classified as a cold steppe climate (Köppen BSk) and 10.8% as a hot steppe climate (Köppen BSh).[38] Temperatures are coolest and rainfall most abundant in the higher elevations of the Davis and Chinati Mountains. By contrast, the lowlands along the Rio Grande along the southern and western areas of the county are dry with often extreme summer daytime heat and where winter snowfall is unusual. Throughout the county, May through October marks the rainy season, while the remainder of the year is predominantly dry.

- Candelaria

- Coordinates: 30.13833°N 104.68222°W

- Elevation: 2,877 feet (877 m)[39]

| Climate data for Candelaria, Texas (Jun 1, 1940–Jul 22, 2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 66.6 (19.2) |

72.4 (22.4) |

80.7 (27.1) |

89.3 (31.8) |

96.6 (35.9) |

101.9 (38.8) |

100.0 (37.8) |

97.7 (36.5) |

92.9 (33.8) |

85.6 (29.8) |

74.6 (23.7) |

66.8 (19.3) |

85.4 (29.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 31.5 (−0.3) |

35.2 (1.8) |

40.6 (4.8) |

48.2 (9.0) |

56.5 (13.6) |

65.3 (18.5) |

68.2 (20.1) |

66.4 (19.1) |

61.5 (16.4) |

49.9 (9.9) |

38.1 (3.4) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

49.4 (9.7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.44 (11) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.27 (6.9) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.65 (17) |

1.48 (38) |

2.17 (55) |

2.26 (57) |

1.99 (51) |

1.19 (30) |

0.39 (9.9) |

0.45 (11) |

12.01 (305) |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute[40] | |||||||||||||

- Marfa

- Coordinates: 30.31250°N 104.07222°W

- Elevation: 4,790 feet (1,460 m)[39]

| Climate data for Marfa #2, Texas (Dec 1, 1958–Jul 31, 2009) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 60.2 (15.7) |

63.9 (17.7) |

71.2 (21.8) |

78.8 (26.0) |

85.8 (29.9) |

91.2 (32.9) |

89.6 (32.0) |

87.5 (30.8) |

83.6 (28.7) |

77.3 (25.2) |

67.6 (19.8) |

60.8 (16.0) |

76.5 (24.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 25.7 (−3.5) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

33.5 (0.8) |

41.4 (5.2) |

50.1 (10.1) |

57.6 (14.2) |

60.2 (15.7) |

59.1 (15.1) |

54.0 (12.2) |

44.1 (6.7) |

33.4 (0.8) |

26.6 (−3.0) |

42.8 (6.0) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.42 (11) |

0.47 (12) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.59 (15) |

1.17 (30) |

1.78 (45) |

2.73 (69) |

2.89 (73) |

2.57 (65) |

1.39 (35) |

0.58 (15) |

0.50 (13) |

15.4 (390.9) |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute[41] | |||||||||||||

- Miller Ranch

Miller Ranch is located in the far north of the county ten miles from Valentine in adjoining Jeff Davis County.

- Coordinates: 30.5525°N 104.64667°W

- Elevation: 4,394 feet (1,339 m)[39]

| Climate data for Valentine 10 WSW, Texas (Mar 1, 1897–Mar 31, 2013) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63.3 (17.4) |

64.0 (17.8) |

72.5 (22.5) |

78.0 (25.6) |

87.7 (30.9) |

93.3 (34.1) |

92.2 (33.4) |

91.1 (32.8) |

87.1 (30.6) |

79.8 (26.6) |

72.1 (22.3) |

63.9 (17.7) |

78.8 (26.0) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 29.2 (−1.6) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

35.7 (2.1) |

42.9 (6.1) |

52.1 (11.2) |

62.6 (17.0) |

64.9 (18.3) |

62.2 (16.8) |

56.4 (13.6) |

46.7 (8.2) |

35.3 (1.8) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

45.2 (7.4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.57 (14) |

0.47 (12) |

0.34 (8.6) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.83 (21) |

1.72 (44) |

2.38 (60) |

2.43 (62) |

2.42 (61) |

1.19 (30) |

0.51 (13) |

0.56 (14) |

13.78 (348.7) |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute[42] | |||||||||||||

- Presidio

- Coordinates: 29.57111°N 104.37139°W

- Elevation: 2,610 feet (796 m)[39]

| Climate data for Presidio, Texas (Oct 1, 1927–Mar 6, 2013) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 67.3 (19.6) |

73.9 (23.3) |

81.9 (27.7) |

90.2 (32.3) |

97.4 (36.3) |

102.6 (39.2) |

101.1 (38.4) |

99.8 (37.7) |

94.9 (34.9) |

87.2 (30.7) |

75.7 (24.3) |

67.4 (19.7) |

86.6 (30.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 33.4 (0.8) |

38.3 (3.5) |

44.6 (7.0) |

53.2 (11.8) |

62.4 (16.9) |

71.2 (21.8) |

73.0 (22.8) |

71.8 (22.1) |

66.5 (19.2) |

55.5 (13.1) |

41.9 (5.5) |

34.4 (1.3) |

53.9 (12.2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.41 (10) |

0.33 (8.4) |

0.18 (4.6) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.64 (16) |

1.22 (31) |

1.54 (39) |

1.43 (36) |

1.48 (38) |

0.91 (23) |

0.38 (9.7) |

0.42 (11) |

9.25 (234.6) |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute[43] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 580 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,636 | 182.1% | |

| 1880 | 2,873 | 75.6% | |

| 1890 | 1,698 | −40.9% | |

| 1900 | 3,676 | 116.5% | |

| 1910 | 5,218 | 41.9% | |

| 1920 | 12,202 | 133.8% | |

| 1930 | 10,154 | −16.8% | |

| 1940 | 10,925 | 7.6% | |

| 1950 | 7,354 | −32.7% | |

| 1960 | 5,460 | −25.8% | |

| 1970 | 4,842 | −11.3% | |

| 1980 | 5,188 | 7.1% | |

| 1990 | 6,637 | 27.9% | |

| 2000 | 7,304 | 10.0% | |

| 2010 | 7,818 | 7.0% | |

| Est. 2019 | 6,704 | [44] | −14.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[45] 1850–2010[46] 2010–2014[1] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, 7,818 people resided in the county. About 85.9% were White, 1.0% Asian, 0.7% Native American, 0.6% Black or African American, 9.9% of some other race, and 1.9% of two or more races; 83.4% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

As of the census[47] of 2000, 7,304 people, 2,530 households, and 1,864 families resided in the county. The population density was 2 people per square mile (1/km²). The 3,299 housing units averaged 1 per square mile (0/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 84.95% White, 0.27% Black or African American, 0.27% Native American, 0.08% Asian, 13.48% from other races, and 0.93% from two or more races. About 84.36% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race.

Of the 2,530 households, 40.40% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.50% were married couples living together, 13.60% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.30% were not families. Around 24.20% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.20% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.85 and the average family size was 3.43.

In the county, the population was distributed as 32.70% under the age of 18, 8.30% from 18 to 24, 24.90% from 25 to 44, 20.20% from 45 to 64, and 13.90% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females there were 94.30 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.00 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $19,860, and for a family was $22,314. Males had a median income of $23,218 versus $16,208 for females. The per capita income for the county was $9,558. About 32.50% of families and 36.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 43.40% of those under age 18 and 44.10% of those age 65 or over. The county's per capita income makes it one of the poorest counties in the United States.

Politics

The county is reliably Democratic. In the 2012 U.S. Presidential Election Barack Obama received 70.56% of the county's vote and Willard Mitt Romney got only 27.74%.[48] In 2008, Barack Obama received 71.3% of the county's vote.[49] Hillary Clinton received 66.2% of the county's vote in the 2016 United States presidential election.[50]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 29.5% 652 | 66.0% 1,458 | 4.4% 98 |

| 2012 | 27.7% 504 | 70.6% 1,282 | 1.7% 31 |

| 2008 | 27.8% 489 | 71.3% 1,252 | 0.9% 16 |

| 2004 | 37.8% 715 | 61.3% 1,159 | 0.9% 16 |

| 2000 | 35.2% 618 | 60.6% 1,064 | 4.3% 75 |

| 1996 | 22.3% 383 | 70.2% 1,205 | 7.5% 128 |

| 1992 | 21.2% 400 | 62.9% 1,189 | 16.0% 302 |

| 1988 | 33.1% 586 | 66.4% 1,176 | 0.5% 9 |

| 1984 | 44.0% 837 | 52.2% 992 | 3.8% 73 |

| 1980 | 40.2% 723 | 57.8% 1,039 | 2.1% 37 |

| 1976 | 35.5% 687 | 63.6% 1,232 | 0.9% 17 |

| 1972 | 53.7% 785 | 46.1% 674 | 0.2% 3 |

| 1968 | 30.4% 481 | 61.3% 969 | 8.3% 132 |

| 1964 | 27.1% 431 | 72.8% 1,156 | 0.1% 1 |

| 1960 | 30.1% 376 | 69.4% 866 | 0.5% 6 |

| 1956 | 48.5% 494 | 50.7% 517 | 0.8% 8 |

| 1952 | 55.4% 770 | 44.6% 621 | |

| 1948 | 18.4% 212 | 78.7% 907 | 3.0% 34 |

| 1944 | 20.6% 211 | 63.3% 648 | 16.1% 165 |

| 1940 | 15.0% 163 | 84.6% 917 | 0.4% 4 |

| 1936 | 10.1% 106 | 89.4% 938 | 0.5% 5 |

| 1932 | 11.5% 112 | 88.3% 863 | 0.2% 2 |

| 1928 | 44.6% 254 | 55.4% 315 | |

| 1924 | 19.5% 68 | 76.7% 267 | 3.7% 13 |

| 1920 | 33.3% 122 | 65.0% 238 | 1.6% 6 |

| 1916 | 9.9% 27 | 89.7% 245 | 0.4% 1 |

| 1912 | 25.3% 87 | 54.4% 187 | 20.4% 70 |

In popular culture

The Howard Hawks film Rio Bravo, released 1959, starring John Wayne, Dean Martin, and Ricky Nelson, was set in Presidio County, but filmed in Tucson.[52]

The Riata house and exteriors for Giant, released 1956, were filmed at Marfa.[53][54][55] The big stars, Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean, and others stayed at the Hotel Paisano for two months.

High Lonesome, released in 1950, starring Chill Wills and John Drew Barrymore, was filmed in Antelope Springs, near Marfa.[56]

The county was mentioned in Hunter during part one of "City Under Siege" in the 1988-89 season.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died at the historic Cibolo Creek Ranch near Shafter, Texas in 2016.

Education

Marfa Independent School District serves eastern Presidio County, while Presidio Independent School District serves western Presidio County

Communities

Census-designated place

Ghost towns

- Adobes

- Casa Piedra

- Fort Holland

- Lindsey City

- Tinaja

See also

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Texas: Individual County Chronologies". Texas Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. The Newberry Library. 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- "Native Peoples of the Trans-Pecos Mountains and Basins During Early Historic Times". Texas Beyond History. UT-Austin. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Jumano-Spanish Relations". Texas Beyond History. UT-Austin. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Foraging Peoples: Chisos and Mansos". Texas Beyond History. UT-Austin. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Itinerary of Juan Domínguez de Mendoza, 1684". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Nicolás López". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Society. 2010-06-15. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Smith, Julie Cauble (2010-06-15). "The Ronquillo Land Grant". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Society. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Perry, Ann; Smith, Deborah; Simons, Helen; Hoyt, Catherine A (1996). A Guide to Hispanic Texas. University of Texas Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-292-77709-5.

- Sharp, Jay W. "Desert Trails: The Chihuahua Trail". Desert USA. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Smith, Julie Cauble (2010-06-12). "Fort Leaton". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Society. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Smith, Julie Cauble (2010-06-12). "Fort Leaton State Historic Site". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Society. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Fort Leaton State Historic Site". Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Smith, Julie Cauble (2010-06-12). "Milton Faver". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Society. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Fortin de la Cienega". Fort Tour Systems, Inc. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Smith, Julie Cauble (2010-06-15). "Presidio County". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Society. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Fort Davis National Historic Site". National Park Service. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Curtis, Nancy C (1998). Black Heritage Sites: The South (v. 2). New Press. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-1-56584-433-9.

- "Fort Davis Buffalo Soldiers". National Park Service. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Baker, T. Lindsay (1991). Ghost Towns of Texas. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 134–136. ISBN 978-0-8061-2189-5.

- "Shafter". Texas Escapes. Texas Escapes - Blueprints For Travel, LLC. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Smith, Julie Cauble (2010-06-15). "Presidio County, Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Coppedge, Clay. "Windmills". Texas Escapes. Texas Escapes - Blueprints For Travel, LLC. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Collier, Michael; Webb, Robert H; Schmidt, John C (1996). Dams & Rivers: Primer on the Downstream Effects of Dams. Diane Pub Co. pp. 28–37. ISBN 978-0-7881-2698-7.

- "Elephant Butte Dam". U.S. Dept of the Interior. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Chinati Mission and History". Chinati Fouindation. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Utley, Dan K; Beeman, Cynthia J (2010). "Ghosts at Mitchell Flats". History Ahead: Stories beyond the Texas Roadside Markers. TAMU Press. pp. 153–162. ISBN 978-1-60344-151-3.

- "Marfa AAF". Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields. Paul Freeman. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Carrigan, William D; Webb, Clive (20 February 2015). "When Americans Lynched Mexicans". The New York TImes.

- Paul, Lee. "Marfa's Legendary Lights". The Old West. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "The Mystery of the Marfa Lights". Texas Escapes. Texas Escapes - Blueprints For Travel, LLC. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Smith, Julie Cauble (2010-06-15). "Marfa Lights". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Society. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Norman, Michael; Scott, Bety (2007). "The Marfa Lights". Haunted America. Tor Books. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7653-1967-8.

- "Marfa Lights". Texas Historical Markers. William Nienke, Sam Morrow. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Marfa Lights". Marfa, Texas. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. (2006). "Main Köppen-Geiger Climate Classes for US counties". Schweizerbart Science Publishers. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- "US COOP Station Map". Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute. Retrieved Mar 26, 2016.

- "CANDELARIA, TEXAS (411416), Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute. Retrieved Mar 26, 2016.

- "MARFA #2, TEXAS (415596), Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute. Retrieved Mar 26, 2016.

- "VALENTINE 10 WSW, TEXAS (419275), Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute. Retrieved Mar 26, 2016.

- "PRESIDIO, TEXAS (417262), Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center, Desert Research Institute. Retrieved Mar 26, 2016.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- "Texas Almanac: Population History of Counties from 1850–2010" (PDF). Texas Almanac. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/statesub.php?year=2012&fips=48377&f=0&off=0&elect=0

- The New York Times Electoral Map (Zoom in on Texas) Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- "Presidential Election Results: Donald J. Trump Wins". The New York Times. August 9, 2017. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- Hawks, Howard (1959-04-04), Rio Bravo, John Wayne, Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, retrieved 2018-07-29

- Ragsdale, Kenneth Baxter (1998). Big Bend Country: Land of the Unexpected. TAMU Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-89096-811-6.

- Leonardo, Magdalin. "The Ruins of Reata, Theatrical Archaeology Part One". James Dean Fans. Archived from the original on 22 June 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Leonardo, Magdalin. "The Ruins of Reata, Theatrical Archaeology Part Two". James Dean Fans. Archived from the original on 28 January 1999. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- May, Alan Le (1950-09-01), High Lonesome, John Drew Barrymore, Chill Wills, John Archer, retrieved 2018-07-29

External links

- Presidio County government's website

- Presidio County from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Presidio County Profile compiled by the Texas Association of Counties

- West Texas Weekly- a local weekly newspaper